|

|

Homepage / Syllabus, Fall 2017 (original syllabus before Hurricane Harvey) (syllabus for Spring 2016)

|

|

|

Instructor: Craig White Office: Bayou 2529-8 Office Hours: 4-7 Monday, 4-7 Tuesday, & by appointment Phone: 281 283 3380 Email: whitec@uhcl.edu

Attendance

policy:

|

midterm

(20-30%)

final exam

(25-35%) |

Reading & Presentation Schedule, fall 2017

No Required Textbooks—all texts online

![]()

Tuesday, 29 August 2017: class canceled due to Hurricane Harvey

|

Tuesday, 5 September 2017: course introduction Instructor presents: Enlightenment & The Federalist Papers, #1 Anne Bradstreet, "In Reference to her Children" + 17th Century / Baroque Purposes of literature: mimesis; entertainment and instruction |

Agenda: introduction, questions? syllabus, daily windows; periods semester assignments, model assignments; presentations ID forms + presentation requests (continue next week) [break] Student introductions; why we read literature of the past? What reactions? periods; Renaissance, next week's assignments: Origin Stories Objectives > obj. 4: which America do we teach? todays texts: Enlightenment / Federalist + 17th Century / Bradstreet |

|

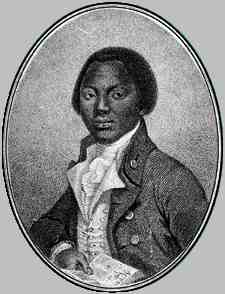

Sacagawea, 1788-1812

|

Student introductions: 1. Name? Student, family, work status? Career plans? 2. Favorite literature? (authors, texts, genres, periods?) (either school reading or personal reading) 3. Recognize any names in our readings? Familiarity with early American literature or history?

Discussion Questions: 1. Why do we read literature of the past? What reactions do we have? What learn or gain? 2. Which America do we learn or teach? Dominant culture / Western Civilization, or Multicultural? 3. What advantages to each? What pressures to teach either?

|

Jefferson Nickel  Monticello |

![]()

early European Exploration and Settlement; First Contact with American Indians

|

|

|

![]()

|

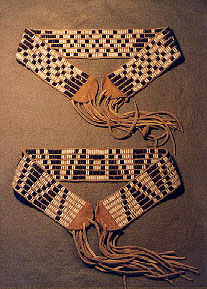

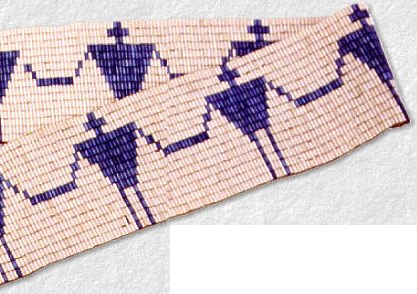

Tuesday, 12 September 2017: Creation & Origin Stories of Europe, America, Africa Readings: Genesis (Creation Story from Bible) & Columbus's Letters (re discovery of America) American Indian Origin Stories Student Presentations Reading Discussion Leader(s): instructor Poem: Simon J. Ortiz, "A New Story"; Poetry Reader: instructor Web Review: Native American music Web Reviewer: instructor Instructor presents Declaration of Independence; Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, the African; Virgin of Guadalupe as Origin Stories terms : origins, intertextuality, syncretism; spoken-written literature; wampum; Art = imitation of reality; to entertain & instruct |

Agenda: emails with link, office hours, presentation assignments (& forms); roll, creation / origin stories & objectives 1 & 2 reading discussion: Columbus, Genesis, & Handsome Lake: intertextuality / dialogue midterm other Amerind creation stories; syncretism poetry: [break] periods; Renaissance American Indian writing? > wampum, etc. web review: > pleasure as identity, defamiliarization? next week's assignments; maps; email with first few presentations |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. How is each creation / origin story unique to its culture? How does an origin story create a culture? What symbols, gender roles, ethics or morality, relations of humanity and divinity? 2. How do today's creation / origin stories resemble each other? If they do resemble each other, is it because of cultural contact or universal human nature? 3. What literary qualities or pleasures do you find in these texts? What balance of instruction and entertainment? 4. What resemblances b/w Columbus & Genesis? With Handsome Lake? If they resemble or reflect each other, what are possible reasons? (Intertextuality) 4a. More directly, how much does Columbus appear to have rediscovered or re-entered the Garden of Eden from Genesis? 5. What assumptions does Columbus make about American Indians, their land and resources relative to the Europeans, their empires, and desires? How do Columbus's attitudes still reflect those of America's dominant culture toward Native American Indians? 6. About "Creation Stories," what advantages to one story vs. many stories? 7. (Objective 3) Which America do we teach? A "nation of many nations," or "one nation under God?" |

Turtle Island |

![]()

|

Tuesday, 19 September 2017: Early Explorers terms: Renaissance, La Malinche, Mestizo Readings: John Smith (1580-1631), from A General History of Virginia (1624) Cabeza de Vaca (1488-1588), selections from La Relacion (1542) Reading Discussion Leader(s): Justin Butler (de Vaca) instructor (Smith) Poem: Sor Juana Inez de Cruz (1651-95), "You Men" Poetry Reader: Tanner House Web review: syncretism (obj. 6) & Virgin of Guadalupe origin story Web Reviewer: Instructor Web Review: European Renaissance music Web Reviewer: Instructor |

Agenda: presentations objectives 3 + 5 & 4: which culture to teach? + development of literature origin stories > Virgin of Guadalupe origin story > Mestizo; Richard Rodriguez Cabeza de Vaca: Justin Sor Juana: Tanner [break] obj. 4 Renaissance > 17c obj. 3; schedule; preview Puritans as dominant culture; origin story > captivity narrative John Smith & Pocahontas: Renaissance > Renaissance music: instructor |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. How do today's reading assignments matter to us here and now? (historicism) 2. What kind of pleasure can be found in these readings? Information and learning, or escape and engagement? 3. (Obj. 4: changing functions and styles of literature) Smith's and de Vaca's accounts are classified as non-fiction, but how are they like both nonfiction and fiction? (Fiction as we now know it barely exists in the 1600s, and won't appear in English for about 200 more years.) 4. What different attitudes toward racial or ethnic mixing emerge from North America and Latin America? Term: Mestizo. 5. Since Cabeza de Vaca's story takes place in the Gulf Coast region (including Galveston and San Antonio), how do you see this area differently through that time and his eyes? 6. What picture emerges of the American Indians, and how does it comply or conflict with legends regarding this area's Indians? Added question: How does the story of John Smith (and its various legends) make an early model of the USA's dominant culture? How may Cabeza de Vaca (and possibly Sor Juana) represent or model a multicultural North America? Another added question: (Obj. 4: changing functions and styles of literature) Smith's and de Vaca's accounts are classified as non-fiction, but how are they like both nonfiction and fiction? |

|

Reformation & Counter-Reformation; Religion as War & Exaltation

|

|

|

|

Tuesday, 26 September 2017: Puritan utopias (1st generation Puritan settlement of New England) Readings: the 17th Century; The Puritans in New England (and England); New England Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (i.e., "the Pilgrims"; selections) John Winthrop (1587-1649), A Model of Christian Charity (Boston Puritans; excerpts) Anne Bradstreet (1612-72), poems term(s): utopia, literary & historical utopias, America's utopian pasts Student Presentations Reading Discussion Leader(s): instructor; (1-2 Bradstreet poems) Poetry Reader: Cynthia Cleveland Web Review: Baroque music Web Reviewer: John Silverio |

Agenda: assignments; which America to teach? > dominant culture Puritans; utopia + grad seminar (communitarian) Bradford / Winthrop: dominant culture / multiculturalism community / individualism; spiritual / material [break] Anne Bradstreet: Cynthia > Baroque & Baroque music: John Silverio

|

|

Stained Glass of Anne Bradstreet |

Discussion Questions: 1. How do the Puritans (with John Smith & Virginia) represent an early model of the USA's dominant culture? How do their relations with American Indians represent or model the relationship between the USA's dominant and minority cultures? Compare and contrast to Cabeza de Vaca and mestizo or Hispanic / Latino culture. 1a. How does the pop-culture resonance of "the first Thanksgiving" with Pilgrims and Indians compare with the populariity of the John Smith-Pocahontas story? How do English & Indian relations compare and contrast with Hispanic / Latino relations in Virgin of Guadalupe & Cabeza de Vaca. 1a. What glimpses do Puritan texts offer of American Indians, and what can we learn of both the Indians and their relations with European settlers? How do the Pilgrims' perceptions of Native Americans conform to or differ from later attitudes? The Pilgrims tell a story of God's plan or story for them, but how do the Indians fit into that plan, or how do you see glimpses of more than one story? 2. How do the Puritans express attitudes that preview constitutional democracy, describe or imagine utopias or perfect worlds, or stand for "traditional family values," or the idea that America was founded by "Godly men?" 2a. How may New England still represent a "utopian community" in American thought or culture? What's changed? 2b. What problems or challenges do the Puritans present to modern America? 3. As lyric poems, Bradstreet's writings appear "timeless." But how do they reach across the centuries? To what do they connect? What parts don't connect? What combinations of family and religious identity make her appealing to popular as well as critical or historical audiences? |

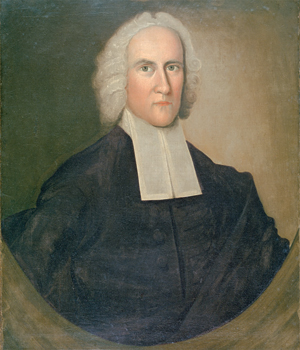

John Winthrop (1587-1649) |

![]()

|

Tuesday, 3 October 2017: Puritan Captivity Narrative (2nd generation of Puritans) Readings: Mary Rowlandson , A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration (1682) introduction + chs. 1-3 of Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison (1725) Cotton Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World (1693) terms: captivity narrative; Iroquois Confederacy; romance Student Presentations Reading Discussion Leader(s): Chelsea Bretherton (Rowlandson); Logan Blair (Jemison) Reading Discussion Leader(s): Sarah Pettigrew (Mather) + Web Review: Salem Witch Trials |

Agenda: assignments; midterm, objectives, Puritan generations Puritans & Indians Rowlandson: Chelsea Jemison: Logan [break] Salem Witch Trials + Mather:

|

|

|

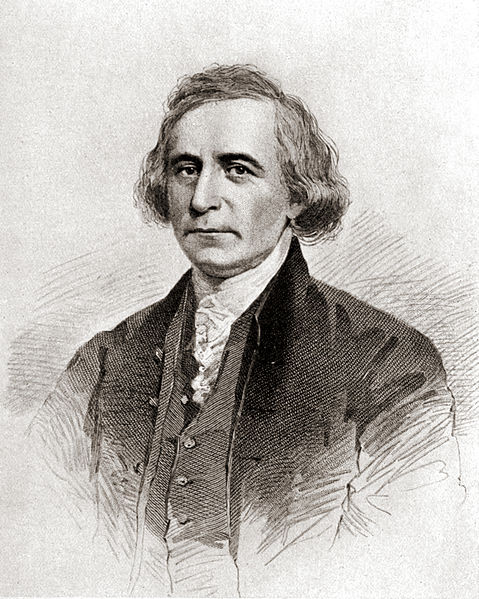

Discussion Questions: 1. Rowlandson, b. 1637, is part of the Puritans' second generation in America, with Mather third generation. (Jonathan Edwards [10 Oct] will be 4th generation.) How do their situations and attitudes differ from first, "utopian" generation of the Puritan immigrants? How do they struggle to "measure up" to the heroic first generation? (Compare immigrant narrative?) 2. See objective 6 re "biblical narratives" as an interpretation of American history. How does Rowlandson interpret both her experience and the Indians' in terms of a Christian allegory or world-vision? 3. Rowlandson writes the first Puritan "captivity narrative"—a popular genre in American literature. What are its attractions? Rowlandson's text was remarkably popular in its day. How does it resemble what we would now consider popular literature that people might enjoy reading? How does it anticipate fiction or the romance? How do Rowlandson's stylings anticipate "the gothic," esp. descriptions of Indians and the wilderness? 4. How do Rowlandson's stylings of Indians correspond to our stylings of terrorists? Even though Rowlandson writes from a dominant-culture perspective, what multicultural glimpses do we get of American Indian culture and the Indians' own struggles in the face of social upheaval? What is their story compared to the dominant-cultural story of righteous conquest? 5. As a woman writer, how do Rowlandson's and Jemison's concerns and style compare to Anne Bradstreet? What are the opportunities for women's writing in early and later New England? (It's easy to criticize the Puritans as sexists, but they were much more encouraging of women's literacy than most early colonial communities, if only so women could read the Bible and learn to obey.) 6. Mather (1663-1728) and the Salem Witch Trials occur in Puritans' third generation—what has changed for God's chosen people in America? Why do we remember the Salem Witch Trials and little else about the Puritans? If we don't believe in witchcraft then or now, what's going on in this trial? Why do Americans want to believe in witches, when they might better wonder why religious superstition was used to murder 20 innocent people and damage countless more? |

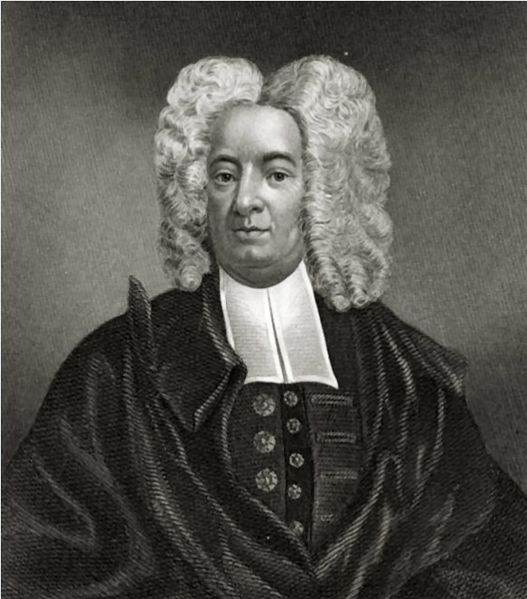

Cotton Mather (1663-1728) |

![]()

The

Enlightenment or Age of Reason

&

the

Scientific Revolution

(late

1600s-late 1700s)

Transition from the 1600s to 1700s, from Religion / Revelation to Enlightenment / Reason

|

Jefferson Memorial, Washington D.C. |

John James Audubon (1785-1851) |

^examples of Neo-Classical or Enlightenment art^

|

Tuesday, 10 October 2017: Last Puritan and First Founder Jonathan Edwards, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God; Personal Narrative; Note on Sarah Pierpont; "Of the Rainbow" & "Of Insects" Benjamin Franklin, Remarks on the Savages of America; from the Autobiography, proverbs / aphorisms Reading Discussion Leader(s): Tanner House (Sinners); Kyle Chapman (Franklin) Web review: Seventeenth Century (1600s); Baroque; Enlightenment, Deism (Franklin Autobio 19, 32), The Greak Awakening; irony Web Reviewer: instructor Web review: remaining chapters of Narrative of Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison (1725) Web Reviewer: Logan Blair |

Agenda: midterm schedule, assignments Edwards: Tanner Franklin: Kyle Mary Jemison: Logan American Indians: what happened, what images |

|

|

Discussion Questions: Above all, compare and contrast Franklin and Edwards, born 3 years apart but on different paths in writing styles and subjects; also public profile & sense of American community. Edwards: Seventeenth-Century blend of intense religion and still-early Scientific Revolution Franklin: Enlightenment / Age of Reason / Scientific Revolution 1. How do the religious postures or attitudes of Edwards and Franklin combine to constitute the USA's continuing status quo of "religious people, secular government?" 2. Which author or text seems most "literary" or "readable" according to present standards? Or, what different tastes do they cater to? 3. Edwards: How is Edwards "the Last Puritan?" What challenges does the Puritan community face? How does he follow earlier Puritan generations? 4. Why is "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" the "most famous sermon ever?" Why do readers remember it? Why does it matter now, whether we share its religion or not? How do Edwards's Personal Narrative & Note on Sarah Pierpont show a different side to religion or a changing attitude toward the world or humanity? 5. Identify elements of the gothic and sublime. (Compare to Rowlandson's Captivity Narrative?) 6. Franklin: In contrast to Edwards as "the Last Puritan," how does Franklin represent the new Enlightenment generation that founds the USA? What aspects of Franklin are more or less attractive or admirable? How does his use of irony and humor allow him to criticize a sensitive subject like religion? |

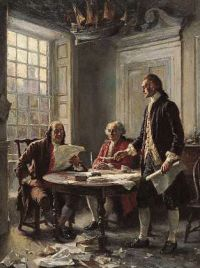

Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), contributor to both the Declaration of Independence & the U.S. Constitution, here conducting experiment w/ lightning / electricity |

|

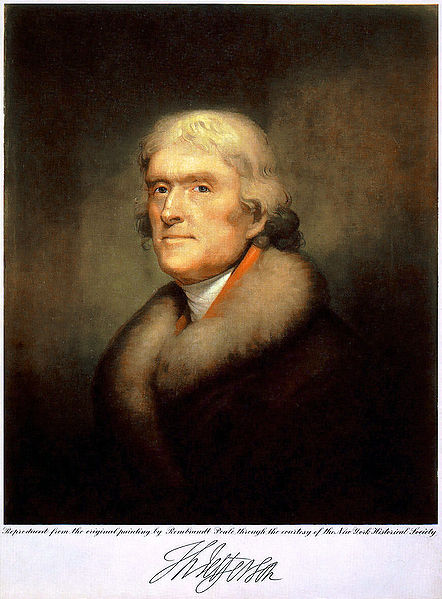

Tuesday, 17 October 2017: Enlightenment and Religion Readings: Thomas Jefferson, writings on religious freedom Thomas Paine, from The Age of Reason, from The Crisis, & from Common Sense Biographical information on Thomas Paine Abigail & John Adams on Dr. Franklin Reading Discussion Leader(s): John Silverio Poem: Jupiter Hammon, "An Evening Thought: Salvation by Christ, with Penitential Cries" (1760) ; Poetry Reader: Instructor Web review: The Enlightenment; Deism; The Great Awakening; Religion & Literature Web Reviewer: instructor Web review: Adam Smith, from The Wealth of Nations (1776) Web Reviewer: instructor |

Agenda: themes for the day modernization, secularism, materialism, etc. (obj. 5) Discussion: John [break] midterm; post-midterm assignments poem: instructor (obj. 3, 4, 5) |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. Compare / contrast Enlightenment writings on religion with Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God and other writings depicting Puritan America as a religious community. 2. What's at stake in the debate over the Founders' religion? How does this debate count as a Creation / Origin Story for the USA in 2017? Consider values, heroes, traditions, change, gender roles, American destiny or mission. 3. What is the Enlightenment style? What are its attractions and detractions, its virtues and shortcomings? (Irony?) (Compare and contrast to Edwards and to Romanticism.) 4. The eighteenth century (1700s) or the Enlightenment is most Literature students' least favorite period of study, yet its literature and history establish the political and economic institutions we continue to live by: science, capitalism, public works, human rights, limited government, separation of church and state. What does this conflict between usefulness and entertainment tell us about literary study and what counts as literature? 5. As in previous class, what model of religion is developing in the USA so that religion remains alive without becoming oppressive, dangerous, or limiting? |

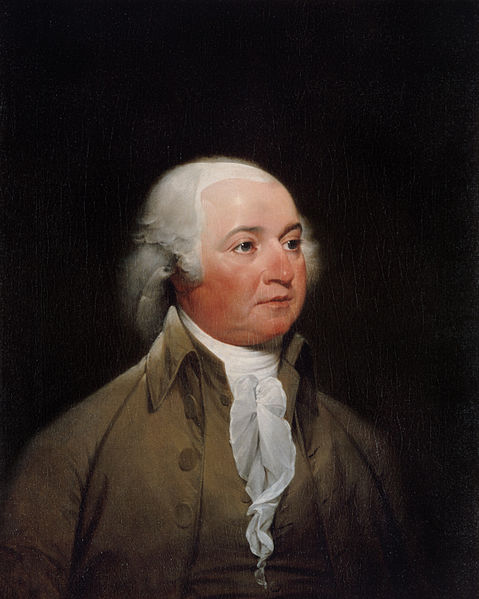

John Adams (1735-1826): 2nd President USA; portrait by Jn Trumbull 1792 |

![]()

Tuesday, 24 October 2017:

official date for midterm

exam, in-class or email;

![]() no class meeting—attendance not required;

instructor keeps office hours.

no class meeting—attendance not required;

instructor keeps office hours.

![]() email submissions

window: 18 October till deadline 25 October 11:59pm

email submissions

window: 18 October till deadline 25 October 11:59pm

![]()

|

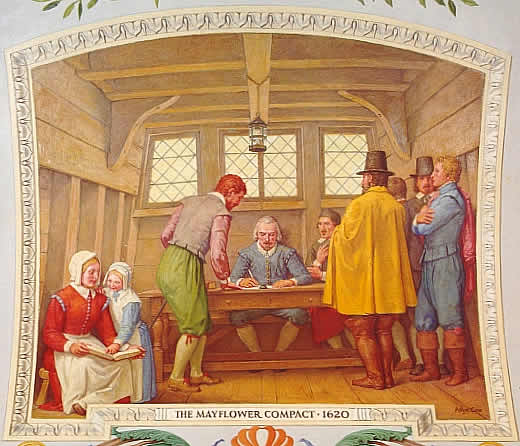

Tuesday, 31 October 2017: Constitutional Government Readings: review Mayflower Compact & A Model of Christian Charity (15 Feb) The Great Law of Peace (Iroquois / Haudenosaunee); The Cherokee Memorials The Declaration of Independence (and its echoes) + Texas Declaration of Independence U.S. Constitution, Articles of Confederation, Instructor Presentation: selections from The Federalist Papers (students welcome to read but not required) Reading Discussion Leader(s): instructor |

Agenda: Protestant Reformation; midterm, schedule review Mayflower Compact Discussion questionss on Declaration, Constitution Model of Christian Charity (?4), capitalism, Bradford Declaration as origin story? assignments Great Law of Peace; Cherokee Memorials > Trail of Tears: |

|

|

Rationale for class on constitutions: Recent scholarship expands the definition of "literature" from creative writing (fiction, poetry, drama) to "extraliterary" texts including historical documents. What are the attractions and downsides of such an expansion? What audiences or constituents does it serve? How does it change the "English Major" or "Literature Major?"—or the teaching of literature and language in public schools? Discussion Questions: 1. What upsides / downsides to reading legal or historical documents as literature? 2. What parts come alive for literary interests and why? Which parts do you skim or ignore, and why? 3. Using process of elimination, if today's texts don't count as literature, what does? How do such questions and analyses help us define literature or extend our definition of literature? As teachers of literature, what are we teaching our students to do? If we should teach historical and legal documents, how can we do so successfully? If we don't, how do we justify teaching the texts that we do teach? 4. Compare the social and religious communities of the Seventeenth Century represented by the Mayflower Compact & A Model of Christian Charity with the Enlightenment social contracts described by The Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. How are the religious documents more "literary" than the Enlightenment documents? 5. As with overtly religious people who never read the Bible, many proudly patriotic Americans never read the Declaration or Constitution, even while claiming these sources support their biases and ideologies. They learn about the Bible from preachers or about the Constitution from family or office conversations or talk radio. What happens when either set of fundamentalists actually read their sacred texts instead of just hearing about them? 6. With our texts and subjects today, how to avoid extreme reactions of apathy, rebellion or righteousness? Readers of government documents often respond fatalistically with "so what?", avoiding controversy. Correspondingly, any effort to read critically can be criticized as disrespecting the past or bringing politics into a classroom. 7. If education and literacy are essential for democratic self-government, will aging white voters support education for children who don't look like them? Or will white population continue "white flight" to suburbs, heartland interior (e.g. Idaho), Bible academies, home schooling? (coursesite homepage) 8. Obj. 3 on "Culture Wars": How do we regard the Founders (or Founding Fathers)? Are they superhuman thinkers, writers, and "statesmen" instead of politicians? Or are they slave-holding racists who ignored women's rights and broke off from England because they didn't want to pay taxes to support their own defense and rights? 9. What are the appeals of reading The Great Law of Peace & The Cherokee Memorials in contrast to the Declaration and Constitution? Why do even dominant-culture students prefer such texts to the nation's founding documents? How do such attitudes anticipate Romanticism? |

Trail of Tears |

![]()

|

Tuesday, 7 November 2017: Who's in and out of the Enlightenment State? (transition to Romanticism) Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative . . . (1789; first slave narrative) (African American) Samson Occom, A Short Narrative of my Life (1768) (American Indian) John Woolman, selections from The Journal (1753, 1762) on The Quaker Page Abigail & John Adams's letters on America's new government Reading Discussion Leader(s): instructor Poem: Phillis Wheatley, "On Being Brought From Africa to America" Poetry Reader: John Silverio Poem: Phillis Wheatley, "On Imagination" Poetry Reader: Marissa Mackey Instructor presents: The Quaker Page |

Agenda: midterms, Model Assignments, final exam; Romanticism religion > politics? > literacy + question of universal humanity Equiano: Wheatley, "Africa to America": John "On Imagination": Marissa [break] Occom: instructor Periods: Enlightenment & Romanticism; assignments > Romanticism / fiction: the Adams letters Quakers & Woolman: instructor |

|

|

Overall Discussion Question: Continuing Obj. 3 "which America to teach," what is gained or lost by reading "outsiders" to the nation's founding and its dominant culture? What literary power or prestige is gained? What do we learn about North American culture, both good and bad? (e.g., a history of exclusion and oppression still with us today, but also ideals and mechanisms for equality and progress?). How may attention to "outsiders" be a feature or value of Romanticism? 1. In both Equiano and Occom, note connections between religion and literacy (and literacy as a prerequisite for enlightened self-government—see Texas Declaration, para. 11). If religion is no longer part of the government (or the economics of capitalism), where does religion relocate and assert its power? 2. How does Equiano's writing in both style and content offer an African American voice and yet resemble the Founders and the Enlightenment? What qualities reconnect to the religious appeals of the Puritans or of evangelical culture? 3. Equiano shows slavery as horrifying, but in contrast to most later, Romantic slave narratives, he mostly advocates its reform rather than its abolition. How is this attitude representative of Enlightenment thinking? Contrast Romanticism. 4. Americans who feel defensive about slavery often point to the existence of slavery in Africa. What similairites and differences between traditional African slavery and modern American slavery? 5. Why do most Literature majors like reading works such as those by Equiano or Occom more than texts by the Founders? How do their lives or writings anticipate Romanticism? 6. Reading Woolman's Journal is like reading the life of a saint. What pleasures or rewards? What benefits and risks of reading moral or pious literature in public schools? What kinds of moral quandaries does Woolman face that prevent or transcend simple yes-no moralism? [43] How does Woolman differ from the Enlightenment? In what ways is he a potentially a Romantic figure, or not? (cf. Thoreau) 6a. What source for morality in a nation without established religion? |

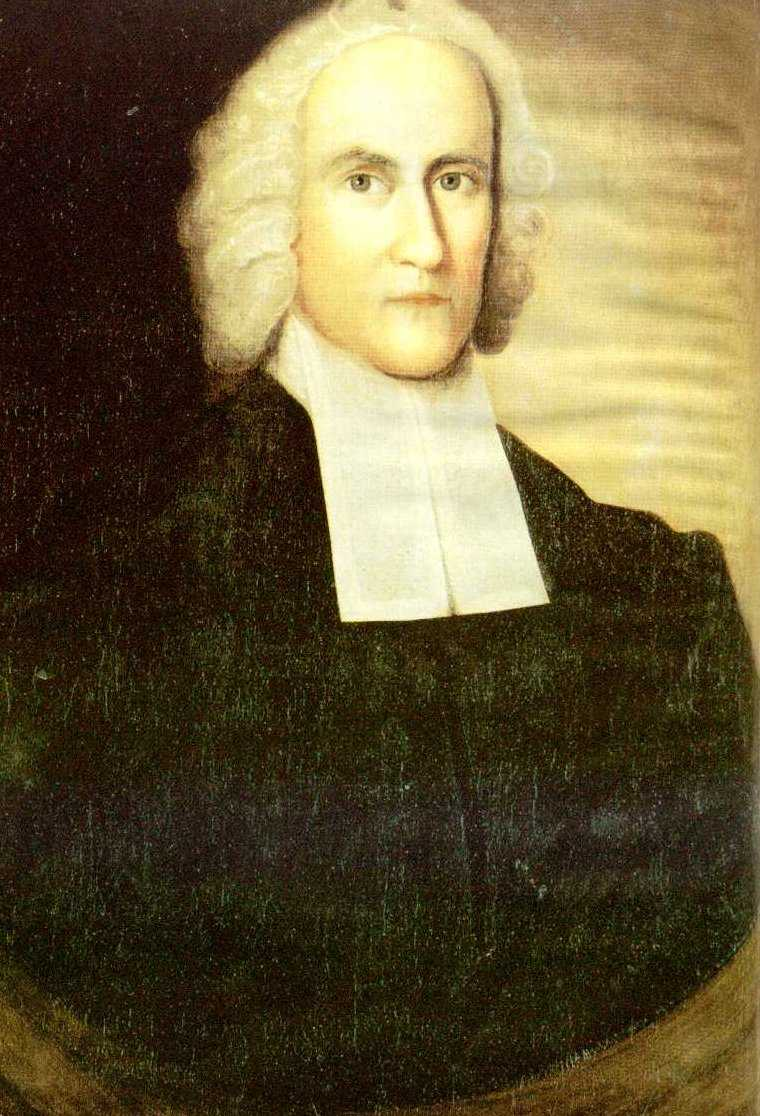

Jonathan Edwards |

![]()

|

Early Romantic Era (late 1700s-early 1800s) 17th Century > Enlightenment > Romanticism

|

|

|

Tuesday, 14 November 2017: Peace, Change, Great Awakenings + begin Women's Romance Readings: Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer (1782) Charlotte Temple (read most of Volume One) Student Presentations Reading Discussion Leader(s): Sarah Pettigrew

|

Agenda: objective 4: Enlightenment / Romanticism early Romanticism: Woolman, Crevecoeur schedule, assignments history of the novel Charlotte Temple: Sarah + instructor nature of fiction; final exam |

|

|

Overall question(s): How do thought, literature, and religion turning from the Enlightenment to Romanticism? Founders challenge: If "all men are created equal" with "unalienable rights," what is meant by men? Are American ideals universal, or limited to people like the Founders? (propertied white men) Crevecoeur: How does Crevecoeur describe "the American" as a new identity created by "the Melting Pot" of assimilation? What contrasts to European nations? Relate to American Exceptionalism.

Charlotte Temple: What balance is struck between "instruction" and "entertainment?"

How does Charlotte's action of leaving her family parallel the USA's Declaration of Independence? Since the Founders and the Enlightenment virtually excluded women, how do Romanticism and fiction involve women in literature? What is the nature of fiction, and how does Charlotte Temple fulfill the style or appeal of a novel? What are Jefferson's misgivings about women's preferences for fiction? |

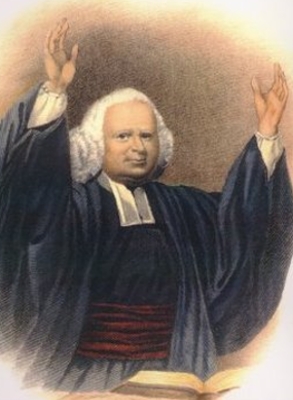

George Whitefield (1714-70) |

![]()

|

Tuesday, 21 November 2017: complete women's romance Readings: Charlotte Temple (complete); historical information on Susanna Rowson & Charlotte Temple Thomas Jefferson, letter on women's education & novels begin Edgar Huntly (chapter 1); term: gothic; novel; fiction; defamiliarization Student Presentations All students have a passage from anywhere in Charlotte Temple for question, comment.

Web review:

Enlightenment / Romantic visual art

Web Reviewer:

|

Agenda: Enlightenment / Romanticism assignments discuss Charlotte Temple (1791) Edgar Huntly Classical classical music: instructor Romantic music & Romantic art: Mason

|

|

|

Class Assignment: All students have a passage from anywhere in Charlotte Temple for question, comment. Discussion Questions: 1. For past generations of college students, Charlotte Temple would likely have been excluded from a Literature course on account of its sentimentality and its appeal to popular rather than critical tastes. What is gained from reading such a novel in terms of women's writing, the romance genre, cultural studies, popular culture, early American history? 2. By reading an early work of fiction like Charlotte Temple, what do you learn about the style of fiction you take for granted now? 3. How is Charlotte Temple like a telenovela, a soap opera, a chick flick, or other current genres of popular literature? 4. Compare / contrast Charlotte Temple as a sentimental romance novel with Edgar Huntly as a gothic romance novel. What different styles or traditions immediately appear? How are both still novels? Continue questions on Charlotte Temple from previous class: What balance is struck between "instruction" and "entertainment?"

How does Charlotte's action of leaving her family in England parallel immigration and the USA's Declaration of Independence? Since the Founders and the Enlightenment virtually excluded women, how do Romanticism and fiction involve women in literature? What is the nature of fiction, and how does Charlotte Temple fulfill the style or appeal of a novel? |

|

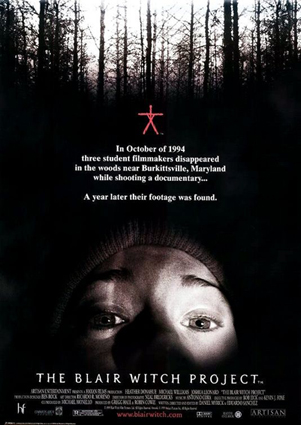

![]()

|

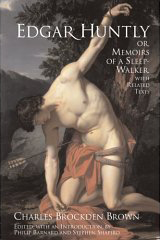

Tuesday, 28 November 2017: Edgar Huntly Readings: Edgar Huntly through chapter 12

Web review:

Life & Career of Charles Brockden

Brown Web Reviewer:

Instructor

Web review: T |

Agenda: History: Romanticism, gothic, and fiction, novel Brown biography discussion questions assignments; preview Freneau evaluations |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. Edgar Huntly was never popular like Charlotte Temple. Why not? How does Edgar Huntly seem more like "classic literature" than Charlotte Temple? What distinctions between popular and classic literature? What balance is struck between "instruction" and "entertainment?" 2. How can both be classified as Romantic (or occasionally anti-Romantic)? 3. Examples of the gothic and sublime in Edgar Huntly? How and why is American gothic attached to the wilderness rather than gothic castles, etc.? What is the significance of the gothic? Why does it keep returning? How does it keep working? 4. Edgar Huntly is the first serious American attempt at serious or literary fiction. What does the author get right and wrong? What can you learn about fiction from these successes and errors, or from early attempts at fiction generally? What do you want more or less of? 5. What is the overall effect on a reader from reading Edgar Huntly? How does this effect or purpose differ from that of previous texts in Early American Literature? (Obj. 2 & 4: How does “Literature” as we know it today emerge from earlier genres like letters, pamphlets, public documents?) |

wilderness gothic |

![]()

|

Tuesday, 5 December 2017: conclude Charles Brockden Brown, Edgar Huntly Readings: Edgar Huntly (complete) All students have a passage from anywhere in Edgar Huntly for question, comment. Poem: Freneau, "The Indian Burying-Ground" Poetry Reader: Kyle Chapman |

Agenda: religion and Romanticism Poem: final exam; models [break + evaluations] Edgar Huntly: student comments exit |

|

|

All students have a passage from anywhere in Edgar Huntly for question, comment in relation to a discussion question above or below, or an issue not addressed by discussion questions. Discussion Questions: Ask any questions regarding expectations for Final Exam Assignment. 1. Does Edgar Huntly come to any satisfying end or resolution? What balance of instruction and entertainment? Since this is a book you never would have read if you hadn't taken this course, can its study be rationalized or justified? 2. Examples of Romanticism, esp. the gothic and sublime? How or why is the gothic attached to the American wilderness rather than gothic castles, etc.?What significance to the gothic? Why does it keep returning? How does it keep working? What about us responds to the gothic? How does the gothic respond to the Enlightenment?

2a. More on the

gothic: How may Edgar & Clithero qualify as

doppelgangers

or twins? Examples of such twinning elsewhere in

gothic literature? (e.g. Poe, the Brontes, Frankenstein)

3. Edgar Huntly was never popular like Charlotte Temple. Why not? What distinctions between classic & popular literature? 3a. Edgar Huntly is the first serious American attempt at "literary fiction"—written not just to sell copies or teach a lesson but to extend and influence the evolution of imaginative content and literary style. What does the novel get right and wrong? What can you learn about fiction from early fiction's successes and errors? What do you want more or less of? 4. A captivity narrative makes part of the novel's action, only now it's fiction. Compare Mary Rowlandson or Mary Jemison. 5. How may Edgar Huntly maintain interest as an example of modern or even Modernist literature? Consider its interest in the unconscious mind (e.g., somnambulism or sleep-walking; gothic as unconscious nightmare-life; also 27.41, 27.47) and the unreliable narrator. |

|

![]()

Tuesday, 12 November 2017: official date of Final Exam — email anytime between 6 December till deadline 11:59pm Wednesday 13 December.

![]()

Course Objectives

Content

1. To learn about early North American and U.S.texts and cultures and make them matter now. (Historicism)

![]() Literature

as shifting balance between

entertainment and instruction.

Literature

as shifting balance between

entertainment and instruction.

2. To read Early American Literature as an origin story about the beginnings and evolution of North American culture and literature.

"Creation Stories" and "Origin Stories" available in course:

![]() Native American

origin stories

Native American

origin stories

![]() The Pilgrim or

Puritan Fathers (& Mothers) of

New England

The Pilgrim or

Puritan Fathers (& Mothers) of

New England

![]() Founding Fathers (& Mothers)

Founding Fathers (& Mothers)

![]() African American slave narratives

African American slave narratives

![]() Hispanic, Latino/a,

Mestizo, or Mexican-American:

the Virgin of Guadalupe

& La Relacion

of Cabeza de Vaca

Hispanic, Latino/a,

Mestizo, or Mexican-American:

the Virgin of Guadalupe

& La Relacion

of Cabeza de Vaca

![]() Genesis and Evolution

Genesis and Evolution

To explore related concepts of progress, utopia, decline, and apocalypse (or end-times)

Emergence of “Literature” as we know it today from earlier genres like letters, pamphlets, public documents; spoken and written literatures and cultures.

3. To reconcile the "Culture Wars" over which America is the real America? Which America to teach?—Dominant culture and / or multicultural?

![]() Which America to teach?

Which America to teach?

-

"Founding" by "great white fathers" (dominant culture) and / or multicultural voices of African America, Native America, Spanish and French colonies, women, and others? (pluralism)

-

To acknowledge “heroes, villains, and victims” as symbols necessary for a good story but also recognize cross-cultural, intertextual, evolutionary, and other narrative dynamics.

-

In brief, can the interaction and exchange of different American peoples be seen and told as evolutionary progress, or must it be seen and told as an apocalyptic showdown between self & other or us & them? Is America in decline or making progress?

![]() "American

Exceptionalism": Is America a religious nation peculiarly blessed by God or

a secular state with people of various beliefs devoted to material progress?

"American

Exceptionalism": Is America a religious nation peculiarly blessed by God or

a secular state with people of various beliefs devoted to material progress?

![]() Is American government a strong, centralized national

state or union commanding the world, or is it an isolationist confederation of state and local governments with

prevailing rights?

Is American government a strong, centralized national

state or union commanding the world, or is it an isolationist confederation of state and local governments with

prevailing rights?

![]() Can there be

a community of individuals? A nation of many nations?

Can there be

a community of individuals? A nation of many nations?

![]() Political Correctness: Language always evolves to match or

control the realities it describes, but such change is not always

comfortable.

Political Correctness: Language always evolves to match or

control the realities it describes, but such change is not always

comfortable.

-

Liberal political correctness: continual evolution of diplomatic language to respect differences, with threats of preachiness and over-sensitivity.

-

Conservative political correctness: code of silence on disruptive identities, though sometimes acknowledged by innuendo or symbolism.

![]() To

ask hard questions without simple or

final answers by using

dialectic discussion methods. (Answers

evolve with changing world.)

To

ask hard questions without simple or

final answers by using

dialectic discussion methods. (Answers

evolve with changing world.)

4. To gain literary and cultural knowledge of historical periods & attempt trans-historical unity.

![]() Renaissance / Age of Exploration

(1500s)

Renaissance / Age of Exploration

(1500s)

![]() Seventeenth Century:

Religious Reformation and Warfare

(1600s)

Seventeenth Century:

Religious Reformation and Warfare

(1600s)

![]() Enlightenment, Age of Reason

(late 1600s-late 1700s)

Enlightenment, Age of Reason

(late 1600s-late 1700s)

![]() Romanticism (late 1700s-1800s)

(continues in LITR 4328 American Renaissance,

fall 2016)

Romanticism (late 1700s-1800s)

(continues in LITR 4328 American Renaissance,

fall 2016)

![]() Can these periods align to produce a

linear narrative of literary progress, if only one that approaches our own

modern standards? What is won and lost by the evolution of one period into

another?

Can these periods align to produce a

linear narrative of literary progress, if only one that approaches our own

modern standards? What is won and lost by the evolution of one period into

another?

![]() How does the function of literature change or evolve from

public legend, myth, or constitution to personal or private

fiction or intimate

lyric poetry?

How does the function of literature change or evolve from

public legend, myth, or constitution to personal or private

fiction or intimate

lyric poetry?

![]() How does “Literature” as we know

it today evolve from earlier genres like letters,

nonfiction narratives or reports, pamphlets, public documents;

spoken and written literatures and

cultures

How does “Literature” as we know

it today evolve from earlier genres like letters,

nonfiction narratives or reports, pamphlets, public documents;

spoken and written literatures and

cultures

5. Can American literary and cultural history tell a single story?

Options:

![]() Development of a distinctly "American Literature" as a national

tradition expressing a unique national character of individualism, mobility,

alienation or triumphalism, etc. (Contrast

trans-Atlantic or

multicultural literature.)

Development of a distinctly "American Literature" as a national

tradition expressing a unique national character of individualism, mobility,

alienation or triumphalism, etc. (Contrast

trans-Atlantic or

multicultural literature.)

![]() Providential

history: from "fate / destiny" to Biblical narratives, incl. models for secular story-telling

Providential

history: from "fate / destiny" to Biblical narratives, incl. models for secular story-telling

![]() Evolution as continuity + change

Evolution as continuity + change

![]() the

romance narrative of quest or

journey as progress or decline

the

romance narrative of quest or

journey as progress or decline

![]() Ongoing transition:

tradition > modernity [>

+ religious or cultural reaction of

retrenchment & revival]

Ongoing transition:

tradition > modernity [>

+ religious or cultural reaction of

retrenchment & revival]

Cross-cultural strategies / techniques:

![]() Mestizo identity

Mestizo identity

![]() Multiculturalism and associated terms

Multiculturalism and associated terms

6. Critical Theory / Critical Thinking

Close reading or formalism: attention to language and its mechanisms

Textuality & Intertextuality—not reading “one text at a time” but how texts create a network of shared meaning

Death of the Author: empowering readers, opposing autobiographical interpretations and "what the author meant to say"

Historicism: reading past literature in its historical context and ours

![]() What aspects of the past do we relate to and why?

If we don't relate, what can we learn from difference?

What aspects of the past do we relate to and why?

If we don't relate, what can we learn from difference?

![]() What is historical and what is

timeless? If “timeless,” what is the connection between them and us?

What is historical and what is

timeless? If “timeless,” what is the connection between them and us?

![]() How can we think of the past? What

are mental powers of storytelling and limits to inclusion?

How can we think of the past? What

are mental powers of storytelling and limits to inclusion?

![]() “History in their own words”—and

not, say, in the language of a modern textbook

“History in their own words”—and

not, say, in the language of a modern textbook

![]() American Studies: the

interdisciplinary study of American identity and culture in literature,

history, religion, gender studies, and economics, whether dominant-culture

or multicultural.

American Studies: the

interdisciplinary study of American identity and culture in literature,

history, religion, gender studies, and economics, whether dominant-culture

or multicultural.

![]() People may exploit the past to

exploit people who know nothing of the past and have to believe what they

hear.

People may exploit the past to

exploit people who know nothing of the past and have to believe what they

hear.

Critical thinking:

![]() unity &

diversity, identity and difference: How to tell a continuous story about America that involves “other

Americas?”

unity &

diversity, identity and difference: How to tell a continuous story about America that involves “other

Americas?”

![]() succession and progression: is America

in decline, in progress, or just

evolving?

succession and progression: is America

in decline, in progress, or just

evolving?

![]() resistance to conspiracy theory while recognizing its

attractions.

resistance to conspiracy theory while recognizing its

attractions.

Teaching

Class Organization

![]() Course webpage as evolving teaching

tool

Course webpage as evolving teaching

tool

![]() online texts for a

face-to-face classroom

online texts for a

face-to-face classroom

![]() Student-led discussions

Student-led discussions

![]() Model Assignments for

peer-instruction

Model Assignments for

peer-instruction

![]() Web

reviews to develop reinforcing knowledge of music, visual art, history,

geography.

Web

reviews to develop reinforcing knowledge of music, visual art, history,

geography.

Attitudes

![]() Build on what students already know (or may recognize or relate to)

Build on what students already know (or may recognize or relate to)

![]() Emphasis less on what to think than on how to think and

discuss, plus familiarity with a subject's terms of discussion

Emphasis less on what to think than on how to think and

discuss, plus familiarity with a subject's terms of discussion

![]() Research posts as knowledge gathering +

exams as opinion and analysis

Research posts as knowledge gathering +

exams as opinion and analysis

![]() Begin inclusion of Meso-America,

Spanish colonization, and Hispanic / Mexican identities

Begin inclusion of Meso-America,

Spanish colonization, and Hispanic / Mexican identities

(webpages for later inclusion)

Review of Latino Catholicism: Transformation in America’s Largest Church (2012) by Timothy Matovina

Annie Murphy Paul,

“Reading Literature Makes Us Smarter and Nicer”

North America