|

Craig White's Literature Courses Fiction |

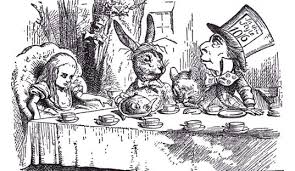

John Tenniel illustration from Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) |

Definitions & etymologies (origins) of fiction from Oxford English Dictionary

fiction Oxford English Dictionary etymology: French fiction < Latin fingere to fashion or form]

3a. The action of ‘feigning’ or inventing imaginary incidents, existences, states of things, etc., whether for the purpose of deception or otherwise. (cf. fabrication) [cf. mimesis]

3b. That which, or something that, is imaginatively invented; feigned existence, event, or state of things; invention as opposed to fact.

4a. The species of literature which is concerned with the narration of imaginary events and the portraiture of imaginary characters; fictitious composition. Now usually, prose novels and stories collectively . . . .

4b. A work of fiction; a novel or tale.

![]()

Fiction as Genre or type of literature

Fiction is, with lyric poetry and drama. one of the main genres of creative literature taught in English or Literature courses (though the essay and other nonfiction genres are also taught as critical responses or contexts to these genres).

Formal sub-genres of fiction include the short story and the novel plus looser categories like the novella, sketch, or tale.

Content sub-genres include the romance novel, gothic novel, adventure novel, science fiction, fantasy, western, spy, mystery, detective novels, etc.

Video & TV dramas or sitcoms and films, movies, or cinema share features with fiction as well as with drama.*

![]()

Formal qualities of fiction

Fiction usually tells a story or narrative—a series of actions or events in scenes where human characters speak and act together.

These two elements—acting and speaking—create two types or sets of voices that distinguish fiction, the novel, or (earlier) the epic:

1. A narrator speaks directly to the reader, describing action, settings, backgrounds & providing other information. This voice may be first-person ("I"), third-person limited (restricted to a character's internal or remembering voice), or third-person omniscient (a perspective that can see everything, including different characters' internal thoughts).

![]()

2. Dialogue: fictional characters speak to each other, not directly to the reader: These voices offer evidence of personalities beyond the narrator's or main character's perspective, providing information the narrator doesn't know until he and the reader hear it. The type of language used often reveals the nature of the character speaking.

(In comparison, the two other main creative genres have different voice-arrangements:

(Lyric poetry is usually delivered by a single voice like the novel's narrator, speaking directly to an audience, as in a popular song.

(Drama shows characters speaking in dialogue to each other, not to the audience, as in a play or movie. Occasionally the audience is directly addressed by a character "breaking the 4th wall" or in classical drama by the chorus, who provide background information in the style of a narrator.)

Fiction has been defended as the greatest or most modern of the three major formal genres of creative writing, especially because its many potential voices give it power or capacity to represent a complex modern social reality with internal or psychological depth. (see M. M. Bakhtin on novel as genre of modern pluralism)

*In film or video the camera or director may sometimes assume functions of a narrator, but drama, film, or video generally lack the "internality" or depth in reporting things unseen that written fiction offers.

Examples for Early American Literature: Edgar Huntly, chapter 3: 28-36. Other early American narratives anticipating fiction:

Mary Rowlandson, Narrative of the Captivity & Restoration (1682): opening as narration; dialogue 19.1a

Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography (1791): mentions Bunyan: 3, 23-4; Remarks on Savages; The Way to Wealth

Louisa May Alcott, Little Women (1868-69)

![]()

Some general formal and content differences between fiction and nonfiction prose:

Nonfiction, as in writing about history, is "what really happened" instead of "what may or could have happened."

The real phenomena of everyday life or historical experience—our names, our needs, our shoes—aren't usually or always symbolic of anything greater than themselves; mostly they just are, unless we invest them with symbolic meaning; e.g., Your room is just your room, unless you suddenly write or say something like, "This room is just like my life—a mess!"

In fiction, however, nearly all data must be symbolic or carry meaning or significance beyond everyday reality; e. g., Almost no fiction represents the everyday reality of tying one's shoes, unless the shoes really matter, like lacing up for a big race or game that will determine a sports scholarship and one's path into the future.

On a larger scale, symbols imply narratives, the stories by which people process reality.

Symbols and narratives also operate in nonfiction genres, but nonfiction genres also contain or refer to details or phenomena that are just facts that carry no symbolic significance beyond their truth among the numberless details and dimensions of reality.

These distinctions between fiction and nonfiction may somewhat parallel those between Romanticism and Realism.

The more we analyze and explain the differences or study examples of these terms, the more exceptions or overlaps we find. Such complications may frustrate final answers, but final answers don't really exist in the study of language and literature. Both keep evolving, and people make them evolve by talking and writing.

![]()

Content qualities of fiction: The types of stories told by novels or short stories are known as narrative genres, spec. comedy, romance, tragedy, satire, or combinations.

Any story may strike us as true or false, likely or outlandish, but fiction "represents" or "imitates" real life or its possibilities rather than depicting actual facts or what exactly happened in history or real life (though this relation has many degrees or variations).

Fiction represents what could plausibly happen among characters who more or less resemble recognizable human types. By extension, the novel's action or feelings could happen to us, the readers, or we can vicariously imagine ourselves in the fictional situation or identify with the characters.

Fiction is therefore usually distinct from history, autobiography, memoir, news reporting (articles), or other nonfiction forms of writing in which actual people or their actions are described. (Ironically, actual events, stories, or characters are often more surprising or unpredictable than fiction. "Truth is stranger than fiction.")

The borders between fiction and nonfiction are not rigid or impermeable; for instance, "historical fiction" may mix fictional and historical characters, or a "roman a clef" ("a novel with a key") may be a fictionalization of real people and events. For instance, Primary Colors (1996) by Anonymous (Joe Klein) represented a thinly veiled description of Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas and his entourage as he prepared to run for the U.S. Presidency.

Typically, though, fiction concerns the private lives of representative people

more than the public life of real people

A standard test of literary quality in drama or fiction is the depth, reality, and variety of characterization. Are the characters in a fiction as different and unique as people in real life? Do they "stand on their own feet?" (The greatest writers are often the writers who can create the greatest characters—Shakespeare, Mark Twain, Cervantes, William Faulkner, Toni Morrison; or consider the lasting vitality of archetypal characters like Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan, James Bond, Jane Eyre, Odysseus, who possess a lifespan greater than fairly any mortal human.)

from Franklin's Autobiography

From

a child I was fond of reading, and all the little money that came into my hands

was ever laid out in books.

Pleased with the

Pilgrim's Progress

[see para. 23

below], my first collection was of John Bunyan's works in

separate little volumes. . . . My

father's little library consisted chiefly of books in polemic divinity

[religious controversy],

most of which I read, and have since often regretted that, at a time when I had

such a thirst for knowledge, more proper books had not fallen in my way since it

was now resolved I should not be a clergyman.

[<note BF’s shift from

religious to classical and practical learning>]

Plutarch's Lives

there was in which I read abundantly, and I still think

that time spent to great advantage. There was also

a book of De Foe's

[author of

Robinson Crusoe], called an Essay on

Projects

[projects = public works],

and another of Dr. Mather's, called

Essays to do Good, which perhaps gave me a turn of thinking that had an

influence on some of the principal future events of my life.

[Times are changing:

Puritan author is read not for sovereignty of God but for self-reliance.]

[

On the way

![]() John Bunyan (English Puritan, 1628-88),

The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678,

1684), a Christian allegory whose style anticipates the realistic novel

a generation later.

John Bunyan (English Puritan, 1628-88),

The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678,

1684), a Christian allegory whose style anticipates the realistic novel

a generation later.

![]() Daniel Defoe (1659-1731),

The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

(1719), widely regarded as the first English novel;

Moll Flanders (1722)

Daniel Defoe (1659-1731),

The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

(1719), widely regarded as the first English novel;

Moll Flanders (1722)

![]() Samuel Richardson (1689-1761),

Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded (1740)

Samuel Richardson (1689-1761),

Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded (1740)

[23]

In

crossing the bay, we met with a squall

[storm]

that tore our rotten sails to pieces, prevented our getting

into the Kill and drove us upon

[24]

I

have since found that it [Pilgrim’s

Progress]

has been translated into most of the languages of

|

|

|

![]()