|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

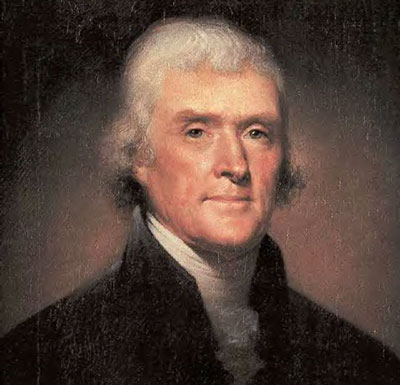

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Nathaniel Burwell on Women's Education including comments on novels (1818) |

|

Dear Sir,

[1]

. . . A plan of female education has never been a

subject of systematic contemplation with me. It has occupied my attention so far

only as the education of my own daughters occasionally required. Considering

that they would be placed in a country situation

[southern USA private education], where little aid could be

obtained from abroad, I thought it essential to give them a solid education,

which might enable them, when become mothers, to educate their own daughters,

and even to direct the course for sons, should their fathers be lost, or

incapable, or inattentive. My surviving daughter accordingly, the mother of many

daughters as well as sons, has made their education the object of her life, and

being a better judge of the practical part than myself, it is with her aid and

that of one of her éleves [students (French)]

that I shall subjoin a catalogue of the books for such a course of reading as we

have practiced. [Any list of books with this letter

is now lost.]

[2] A great obstacle to good education

is the

inordinate passion prevalent for novels,

and the time lost in that reading which

should be instructively employed. When this poison infects the mind, it

destroys

its tone and revolts it against wholesome reading. Reason and fact, plain and

unadorned, are rejected. Nothing can engage attention unless dressed in all the

figments of fancy, and nothing so bedecked comes amiss. The result is a bloated

imagination, sickly judgment, and disgust towards all the real businesses of

life. [classic

Enlightenment

attack on Romanticism]

[2a]

This mass of trash, however, is

not without some distinction; some few

modelling their narratives, although fictitious, on the incidents of real life,

have been able to make them

interesting and useful vehicles of sound morality.

Such, I think, are Marmontel's new moral tales, but not his old ones, which are

really immoral. Such are the writings of Miss

[Maria]

Edgeworth [novelist, 1786-1849],

and some of those of Madame Genlis

[1746-1830,

French author & educator]. For a like reason, too, much poetry should not

be indulged. Some is useful for forming style and taste. Pope, Dryden, Thompson,

Shakspeare, and of the French, Molière, Racine, the Corneilles, may be read with

pleasure and improvement.

[3] The

French language, become that of the

general intercourse

[medium, common language] of nations, and from their

[the French people's] extraordinary advances, now the

depository of all science, is an indispensable part of education for both sexes.

In the subjoined catalogue, therefore, I have placed the books of both languages

indifferently, according as the one or the other offers what is best.

[4]

The ornaments

[refinements] too, and the amusements of life, are entitled to

their portion of attention. These, for a female, are dancing, drawing,

and music. The first is a healthy exercise, elegant and very attractive

for young people. Every affectionate parent would be pleased to see his daughter

qualified to participate with her companions, and without awkwardness at least,

in the circles of festivity, of which she occasionally becomes a part. It is a

necessary accomplishment, therefore, although of short use, for

the

French rule is wise, that no lady dances after marriage. This is

founded in solid physical reasons, gestation and nursing leaving little time to

a married lady when this exercise can be either safe or innocent. Drawing is

thought less of in this country than in Europe. It is an innocent and engaging

amusement, often useful, and a qualification not to be neglected in one who is

to become a mother and an instructor. Music is invaluable where a person has an

ear. Where they have not, it should not be attempted. It furnishes a delightful

recreation for the hours of respite from the cares of the day, and lasts us

through life. The taste of this country, too, calls for this accomplishment

[music] more

strongly than for either of the others.

[5]

I need say nothing of household

economy, in which the mothers of our country are generally skilled, and

generally careful to instruct their daughters. We all know its value, and that

diligence and dexterity in all its processes are inestimable treasures. The

order and economy of a house are as honorable to the mistress as those of the

farm to the master, and if either be neglected, ruin follows, and children

destitute of the means of living.

[6] This, Sir, is offered as a summary sketch on a subject on which I have not thought much. It probably contains nothing but what has already occurred to yourself, and claims your acceptance on no other ground than as a testimony of my respect for your wishes, and of my great esteem and respect.

—

[ ]x