|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

| classic slave narratives:

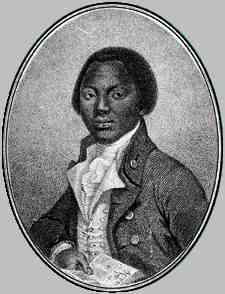

selections from The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, . . . the African by Olaudah Equiano (London, 1789) |

|

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, . . . the African

Epistle Dedicatory [letter of dedication]

Behold, God is my salvation; I will trust and not be

afraid for the Lord Jehovah is my Strength and my Song; He also is become my

Salvation.

And in that day shall ye say, Praise the Lord, call upon his

name, declare his doings among the people. (Isaiah xii. 2, 4).

To

the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and the Commons of

the Parliament of

Great Britain.

My Lords and Gentlemen,

PERMIT me, with

the greatest deference and respect, to lay at your feet the following

genuine Narrative; the Chief design

[purpose]

of which is to excite in your august assemblies a sense of

compassion for the miseries which the Slave-Trade has entailed on my

unfortunate countrymen.

By the horrors of that trade was I

first torn away from all the tender connexions that were naturally dear to my

heart; but these, through the mysterious ways of Providence, I ought to regard

as infinitely more than compensated by the introduction I have thence obtained

to the knowledge of the Christian religion, and of a nation which, by its

liberal sentiments, its humanity, the glorious freedom of its government, and

its proficiency in arts and sciences, has exalted the dignity of human nature.

I am sensible I ought to entreat your pardon for addressing to

you a work so wholly devoid of literary merit; but, as the production of an

unlettered African, who is actuated by the hope of becoming an instrument

towards the relief of his suffering countrymen, I trust that such a man,

pleading in such a cause, will be acquitted of boldness and presumption.

May the God of heaven inspire your hearts with peculiar benevolence

on that important day when the question of Abolition is to be discussed,

when thousands, in consequence of your Determination, are to look for Happiness

or Misery!

I am, My Lords and Gentlemen, Your most obedient, And

devoted humble Servant, OLAUDAH EQUIANO . . .

March 24, 1789.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Maps

relevant to

Narrative of Life of Olaudah Equiano

|

|

Location of present-day Nigeria, which includes former territory of Benin Empire |

|

|

(This Benin region and Empire do not overlap with modern Republic of Benin [formerly Dahomey], a nation to the immediate west of Nigeria.) |

|

|

from Chapter 1 The author's account of his

country, and their manners and customs . . . |

[ch. 1, par. 1] . . . That part of Africa, known by the name of Guinea [west Africa region incl. Nigeria], to which the trade for slaves is carried on, extends along the coast above 3400 miles, from the Senegal to Angola, and includes a variety of kingdoms. Of these the most considerable is the kingdom of Benen [Benin] . . . This kingdom is divided into many provinces or districts: in one of the most remote and fertile of which, called Eboe [modern Ibo or Igbo, southern region of modern Nigeria; a.k.a. Biafra] , I was born, in the year 1745, in a charming fruitful vale [valley], named Effaka. The distance of this province from the capital of Benin and the sea coast must be very considerable; for I had never heard of white men or Europeans, nor of the sea: and our subjection to the king of Benin was little more than nominal; for every transaction of the government, as far as my slender observation extended, was conducted by the chiefs or elders of the place. The manners and government of a people who have little commerce with other countries are generally very simple; and the history of what passes in one family or village may serve as a specimen of a nation.

[ch. 1, par. 2] My father was one of those elders or chiefs I have spoken of, and was styled Embrence; a term, as I remember, importing the highest distinction, and signifying in our language a mark of grandeur. This mark is conferred on the person entitled to it by cutting the skin across at the top of the forehead, and drawing it down to the eye-brows; and while it is in this situation applying a warm hand, and rubbing it, until it shrinks up into a thick weal [ridge] across the lower part of the forehead. Most of the judges and senators were thus marked . . . . Those Embrence, or chief men, decided disputes and punished crimes; for which purpose they always assembled together. The proceedings were generally short; and in most cases the law of retaliation prevailed. I remember a man was brought before my father, and the other judges, for kidnapping a boy; and, although he was the son of a chief or senator, he was condemned to make recompense [restitution] by a man or woman slave. . . .

[ch. 1, par. 3] We are all of a nation of dancers, musicians and poets. Thus every great event, such as a triumphant return from battle, or other cause of public rejoicing is celebrated in public dances, which are accompanied with songs and music suited to the occasion. The assembly is separated into four divisions, which dance either apart or in succession, and each with a character peculiar to itself. The first division contains the married men, who in their dances frequently exhibit feats of arms, and the representation of a battle. To these succeed the married women, who dance in the second division. The young men occupy the third; and the maidens the fourth. [<highly structured traditional society] Each represents some interesting scene of real life, such as a great achievement, domestic employment, a pathetic story or some rural sport; and as the subject is generally founded on some recent event, it is therefore ever new. This gives our dances a spirit and variety which I have scarcely seen elsewhere. We have many musical instruments, particularly drums of different kinds . . . .

[ch. 1, par. 4] As our manners are simple, our luxuries are few [<contrast modern capitalism's multiplications of commodities and desires] . . . . Our manner of living is entirely plain . . . . Our vegetables are mostly plantains, eadas, yams, beans, and Indian corn. The head of the family usually eats alone; his wives and slaves have also their separate tables. Before we taste food we always wash our hands: indeed our cleanliness on all occasions is extreme; but on this it is an indispensable ceremony. After washing, libation is made, by pouring out a small portion of the food, in a certain place, for the spirits of departed relations, which the natives suppose to preside over their conduct and guard them from evil. They are totally unacquainted with strong or spirituous liquours; and their principal beverage is palm wine. . . . The same tree also produces nuts and oil. . . .

[ch. 1, par. 5] As we live in a country where nature is prodigal of her favours, our wants are few and easily supplied; of course we have few manufactures. . . . In such a state money is of little use; however we have some small pieces of coin, if I may call them such. They are made something like an anchor; but I do not remember either their value or denomination. We have also markets, at which I have been frequently with my mother. These are sometimes visited by stout mahogany-coloured men from the south west of us: we call them Oye-Eboe, which term signifies red men living at a distance. They generally bring us fire-arms, gunpowder, hats, beads, and dried fish. . . . They always carry slaves through our land; but the strictest account is exacted of their manner of procuring them before they are suffered to pass. Sometimes indeed we sold slaves to them, but they were only prisoners of war, or such among us as had been convicted of kidnapping or adultery, and some other crimes, which we esteemed heinous. This practice of kidnapping induces me to think, that, notwithstanding all our strictness their principal business among us was to trepan [ambush] our people. I remember too they carried great sacks along with them, which not long after I had an opportunity of fatally seeing applied to that infamous purpose.

[ch. 1, par. 6] Our land is uncommonly rich and fruitful, and produces all kinds of vegetables in great abundance. . . . All our industry is exerted to improve those blessings of nature. Agriculture is our chief employment; and every one, even the children and women, are engaged in it. Thus we are all habituated to labour from our earliest years. Every one contributes something to the common stock; and as we are unacquainted with idleness, we have no beggars. The benefits of such a mode of living are obvious. The West India planters prefer the slaves of Benin or Eboe to those of any other part of Guinea, for their hardiness intelligence, integrity, and zeal. Those benefits are felt by us in the general healthiness of the people, and in their vigour and activity; I might have added too in their comeliness. Deformity is indeed un-known amongst us, I mean that of shape. Numbers of the natives of Eboe now in London might be brought in support of this assertion: for, in regard to complexion, ideas of beauty are wholly relative. I remember while in Africa to have seen three negro children, who were tawny, and another quite white, who were universally regarded by myself, and the natives in general, as far as related to their complexions, as deformed. Our women too were in my eyes at least uncommonly graceful, alert and modest to a degree of bashfulness nor do I remember to have ever heard of an instance of incontinence amongst them before marriage. They are also remarkably cheerful. . . .

[ch. 1, par. 7] As to religion, the natives believe that there is one Creator of all things, and that he lives in the sun, and is girted round with a belt that he may never eat or drink; but, according to some, he smokes a pipe, which is our own favourite luxury. They believe he governs events, especially our deaths or captivity; but, as for the doctrine of eternity, I do not remember to have ever heard of it: some however believe in the transmigration of souls in a certain degree. Those spirits, which are not transmigrated, such as our dear friends or relations, they believe always attend them, and guard them from the bad spirits or their foes. For this reason they always before eating, as I have observed, put some small portion of the meat, and pour some of their drink, on the ground for them; and they often make oblations [honorific gifts] of the blood of beasts or fowls at their graves. I was very fond of my mother, and almost constantly with her. When she went to make these oblations at her mother's tomb, which was a kind of small solitary thatched house, I sometimes attended her. There she made her libations, and spent most of the night in cries and lamentations. I have been often extremely terrified on these occasions. The loneliness of the place, the darkness of the night, and the ceremony of libation, naturally awful and gloomy, were heightened by my mother's lamentations; and these, concurring with the cries of doleful birds, by which these places were frequented, gave an inexpressible terror to the scene. [a gothic note?]

[ch. 1, par. 8] . . . We practised circumcision like the Jews, and made offerings and feasts on that occasion in the same manner as they did. Like them also, our children were named from some event, some circumstance, or fancied foreboding at the time of their birth. I was named Olaudah which, in our language, signifies vicissitude or fortune; also, one favoured, and having a loud voice and well spoken. I remember we never polluted the name of the object of our adoration; on the contrary, it was always mentioned with the greatest reverence; and we were totally unacquainted with swearing . . . .

[ch. 1, par. 9] These instances, and a great many more which might be adduced; while they show how the complexions of the same persons vary in different climates, [it is hoped they] may tend also to remove the prejudice that some conceive against the natives of Africa on account of their colour. Surely the minds of the Spaniards did not change with their complexions! Are there not causes enough to which the apparent inferiority of an African may be ascribed, without limiting the goodness of God, and supposing he forbore to stamp understanding on certainly his own image, because "carved in ebony." Might it not naturally be ascribed to their situation? When they come among Europeans, they are ignorant of their language, religion, manners, and customs. Are any pains taken to teach them these? Are they treated as men? Does not slavery itself depress the mind, and extinguish all its fire and every noble sentiment? But, above all, what advantages do not a refined people possess over those who are rude and uncultivated. Let the polished and haughty European recollect that his ancestors were once, like the Africans, uncivilized, and even barbarous. Did Nature make them inferior to their sons? And should they too have been made slaves? Every rational mind answers, No. Let such reflections as these melt the pride of their superiority into sympathy for the wants and miseries of their fable brethren, and compel them to acknowledge, that understanding is not confined to feature or colour. If, when they look round the world, they feel exultation, let it be tempered with benevolence to others, and gratitude to God, "who hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth; and whose wisdom is not our wisdom, neither are our ways his ways." . . .

[ch. 1, par. 14] These instances, and a great many more which might be adduced; while they

show how the complexions of the same persons vary in different

climates, [it is hoped they] may tend also to

remove the

prejudice that some conceive against the natives of Africa on account of their

colour. Surely the minds of the Spaniards did not change with their

complexions! Are there not causes enough to which the apparent inferiority of an

African may be ascribed, without limiting the goodness of God*,

and supposing he forbore to stamp understanding on certainly his own image,

because "carved in ebony." Might it not naturally be ascribed to their

situation? When they come among Europeans, they are ignorant of their language,

religion, manners, and customs. Are any pains taken to teach them these? Are

they treated as men? Does not slavery itself depress the mind, and

extinguish all its fire and every noble sentiment? But, above all, what

advantages do not a refined people possess over those who are rude and

uncultivated. Let the polished and haughty European recollect that his ancestors

were once, like the Africans, uncivilized, and even barbarous. Did Nature make

them inferior to their sons? And should they too have been made slaves?

Every rational mind answers, No. Let such reflections as these melt the

pride of their superiority into sympathy for the wants and miseries of their

fable brethren, and compel them to acknowledge, that understanding is not

confined to feature or colour. If, when they look round the world, they feel

exultation, let it be tempered with benevolence to others, and gratitude to God,

"who hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of

the earth; and whose wisdom is not our wisdom, neither are our ways his ways."

[compare William

Apess, An Indian's Looking Glass for the White Man (1833), para. 9]

![]()

|

from Chapter 2: The author's birth and parentage—His being kidnapped with his sister—Their separation-surprise at meeting again—. . . |

[ch. 2, par. 1] .

. . I have already acquainted the reader with the time and

place of my birth. My father, besides many slaves, had a numerous family, of

which seven lived to grow up, including myself and a sister, who was the only

daughter. As I was the youngest of the sons, I became, of course, the greatest

favourite with my mother, and was always with her; and she used to take

particular pains to form my mind. I was trained up from my earliest years in the

art of war; my daily exercise was shooting and throwing javelins; and my mother

adorned me with emblems [tattoos? scarification?], after the manner of our greatest warriors. In this way

I grew up till I was turned the age of eleven, when an end was put to my

happiness in the following manner.

[ch. 2, par. 3] Generally when the grown people in the neighborhood were

gone far in the fields to labour, the children assembled together in some of the

neighbors' premises to play; and commonly some of us used to

get up a tree to

look out for any assailant, or kidnapper, that might come upon us; for they

sometimes took those opportunities of our parents' absence to attack and carry

off as many as they could seize. One day, as I was watching at the top of a tree

in our yard, I saw one of those people come into the yard of our next neighbor

but one, to kidnap, there being many stout young people in it. Immediately on

this I gave the alarm of the rogue, and he was surrounded by the stoutest of

them, who entangled him with cords, so that he could not escape till some of the

grown people came and secured him.

[ch. 2, par. 4] But alas! ere long it was my fate to be thus attacked, and to be carried off, when none of the grown people were nigh. One day, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls and in a moment seized us both, and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, and ran off with us into the nearest wood. Here they tied our hands, and continued to carry us as far as they could, till night came on, when we reached a small house where the robbers halted for refreshment, and spent the night. We were then unbound, but were unable to take any food; and, being quite overpowered by fatigue and grief, our only relief was some sleep, which allayed our misfortune for a short time.

[ch. 2, par. 5] The next morning we left the house,

and continued travelling all the day. For a long time we had kept the woods, but

at last we came into a road which I believed I knew. I had now some hopes of

being delivered; for we had advanced but a little way before I discovered some

people at a distance, on which I began to cry out for their assistance: but my

cries had no other effect than to make them tie me faster and stop my mouth, and

then they put me into a large sack. They also stopped my sister's mouth, and

tied her hands; and in this manner we proceeded till we were out of the sight of

these people. When we went to rest the following night they offered us some

victuals; but we refused it; and the only comfort we had was in being in one

another's arms all that night, and bathing each other with our tears. But alas!

we were soon deprived of even the small comfort of weeping together.

[ch. 2, par. 6] The next day proved a day of greater sorrow than I had

yet experienced; for my sister and I were then separated, while we lay clasped

in each other's arms. It was in vain that we besought them not to part us; she

was torn from me, and immediately carried away, while I was left in a state of

distraction not to be described. I cried and grieved continually; and for

several days I did not eat anything but what they forced into my mouth. At

length, after many days travelling, during which I had often changed masters I

got into the hands of a chieftain, in a very pleasant country. This man had two

wives and some children, and they all used me extremely well, and did all they

could to comfort me; particularly the first wife, who was something like my

mother. Although I was a great many days journey from my father's house, yet

these people spoke exactly the same language with us.

[ch. 2, par. 7] This first master of mine, as I may

call him, was a smith

[a blacksmith], and my principal employment was working his bellows,

which were the same kind as l had seen in my vicinity. They were in some

respects not unlike the stoves here in gentlemen's kitchens; and were covered

over with leather; and in the middle of that leather a stick was fixed and a

person stood up, and worked it, in the same manner as is done to pump water out

of a cask with a hand pump. I believe it was gold he worked, for it was of a

lovely bright yellow color, and was worn by the women on their wrists and

ankles. I was there I suppose about a month, and they at last used to trust me

some little distance from the house. This liberty I used in embracing every

opportunity to inquire the way to my own home: and I also sometimes, for the

same purpose, went with the maidens, in the cool of the evenings, to bring

pitchers of water from the springs for the use of the house. I had also remarked

where the sun rose in the morning, and set in the evening, as I had travelled

along; and I had observed that my father's house was towards the rising of the

sun. I therefore determined to seize the first opportunity of making my escape,

and to shape my course for that quarter; for I was quite oppressed and weighed

down by grief after my mother and friends; and my love of liberty, ever great,

was strengthened by the mortifying circumstance of not daring to eat with the

free-born children, although I was mostly their companion. . . .

[ch. 2, par. 8] Soon after this my master's only daughter, and child by

his first wife, sickened and died, which affected him so much that for some time

he was almost frantic, and really would have killed himself, had he not been

watched and prevented. However, in a small time afterwards he recovered, and I

was again sold. I was now carried to the left of the sun's rising, through many

different countries, and a number of large woods. The people I was sold to used

to carry me very often, when I was tired, either on their shoulders or on their

backs. I saw many convenient well-built sheds along the roads, at proper

distances, to accommodate the merchants and travelers, who lay in those

buildings along with their wives, who often accompany them; and they always go

well armed.

[ch. 2, par. 9] From the time I left my own nation I always found

somebody that understood me till I came to the sea coast. The languages of

different nations did not totally differ, nor were they so copious as those of

the Europeans, particularly the English. They were therefore easily learned;

and, while I was journeying thus through Africa, I acquired two or three

different tongues. In this manner I had been travelling for a considerable time,

when one evening to my great surprise, whom should I see brought to the house

where I was but my dear sister! As soon as she saw me she gave a loud shriek,

and ran into my arms. I was quite overpowered: neither of us could speak; but,

for a considerable time, clung to each other in mutual embraces, unable to do

anything but weep. Our meeting affected all who saw us; and indeed I must

acknowledge, in honor of those fable destroyers of human rights, that I never

met with any ill treatment, or saw any offered to their slaves, except tying

them, when necessary, to keep them from running away. When these people knew we

were brother and sister they indulged us together; and the man, to whom I

supposed we belonged, lay with us, he in the middle, while she and I held one

another by the hands across his breast all night; and thus for a while we forgot

our misfortunes in the joy of being together: but even this small comfort was

soon to have an end; for scarcely had the fatal morning appeared, when she was

again torn from me forever! I was now more miserable, if possible, than before.

[ch. 2, par. 10] The small relief which her presence gave me from pain was gone, and the wretchedness of my situation was redoubled by my anxiety after her fate, and my apprehensions lest her sufferings should be greater than mine, when I could not be with her to alleviate them. Yes, thou dear partner of all my childish sports! Thou sharer of my joys and sorrows! happy should I have ever esteemed myself to encounter every misery for you, and to procure your freedom by the sacrifice of my own. Though you were early forced from my arms, your image has been always riveted in my heart, from which neither time nor fortune have been able to remove it; so that, while the thoughts of your sufferings have damped my prosperity, they have mingled with adversity and increased its bitterness. To that Heaven which protects the weak from the strong, I commit the care of your innocence and virtues, if they have not already received their full reward, and if your youth and delicacy have not long since fallen victims to the violence of the African trader, the pestilential stench of a Guinea ship, the seasoning in the European colonies, or the lash and lust of a brutal and unrelenting overseer.

[ch. 2, par. 11] I did not long remain after my sister. I was again sold, and carried through a number of places, till, after travelling a considerable time, I came to a town called Tinmah, in the most beautiful country I had yet seen in Africa. It was extremely rich, and there were many rivulets which flowed through it, and supplied a large pond in the center of the town, where the people washed. Here I first saw and tasted cocoa-nuts, which I thought superior to any nuts I had ever tasted before; and the trees, which were loaded, were also interspersed amongst the houses, which had commodious shades adjoining, and were in the same manner as ours, the insides being neatly plastered and whitewashed. Here I also saw and tasted for the first time sugar-cane. Their money consisted of little white shells, the size of the finger nail. I was sold here for one hundred and seventy-two of them by a merchant who lived and brought me there. I had been about two or three days at his house, when a wealthy widow, a neighbor of his, came there one evening, and brought with her an only son, a young gentleman about my own age and size. Here they saw me; and, having taken a fancy to me, I was bought of the merchant, and went home with them. [<example of Old-World slavery as extended family>]

[ch. 2, par. 12] Her house and premises were

situated close to one of those rivulets I have mentioned, and were the finest I

ever saw in Africa: they were very extensive, and she had a number of slaves to

attend her. The next day I was washed and perfumed, and when meal-time came I

was led into the presence of my mistress, and ate and drink before her with her

son. This filled me with astonishment; and I could scarce help expressing my

surprise that the young gentleman should suffer

[permit] me, who was bound

[enslaved], to eat with

him who was free; and not only so, but that he would not at any time either eat

or drink till I had taken first, because I was the eldest, which was agreeable

to our custom. Indeed everything here, and all their treatment of me, made me

forget that I was a slave. The language of these people resembled ours so

nearly, that we understood each other perfectly. They had also the very same

customs as we. There were likewise slaves daily to attend us, while my young

master and I with other boys sported with our darts and bows and arrows, as I

had been used to do at home. In this resemblance to my former happy state I

passed about two months; and I now began to think I was to be adopted into the

family, and was beginning to be reconciled to my situation, and to forget by

degrees my misfortunes when all at once the delusion vanished; for, without the

least previous knowledge, one morning early, while my dear master and companion

was still asleep, I was wakened out of my reverie to fresh sorrow, and hurried

away even amongst the uncircumcised.

[ch. 2, par. 13] Thus, at the very moment I

dreamed of the greatest

happiness, I found myself most miserable; and it seemed as if fortune wished to

give me this taste of joy, only to render the reverse more poignant. The change

I now experienced was as painful as it was sudden and unexpected. It was a

change indeed from a state of bliss to a scene which is inexpressible by me, as

it discovered to me an element I had never before beheld, and till then had no

idea of, and wherein such instances of hardship and cruelty continually occurred

as I can never reflect on but with horror.

[ch. 2, par. 14] All the nations and people I had hitherto passed through

resembled our own in their manners, customs, and language: but I came at length

to a country, the inhabitants of which differed from us in all those

particulars. I was very much struck with this difference, especially when I came

among a people who did not circumcise, and are without washing their

hands. They cooked also in iron pots, and had European cutlasses and cross bows,

which were unknown to us and fought with their fists amongst themselves. Their

women were not so modest as ours, for they ate, and drank, and slept, with their

men. But, above all, I was amazed to see no sacrifices or offerings among them.

In some of those places the people ornamented themselves with scars, and

likewise filed their teeth very sharp. They wanted sometimes to ornament me in

the same manner, but I would not suffer them; hoping that I might sometime be

among a people who did not thus disfigure themselves, as I thought they did.

[ch. 2, par. 15] At last I came to the banks of a

large river, which was covered with canoes, in which the people appeared to live

with their household utensils and provisions of all kinds. I was beyond measure

astonished at this, as I had never before seen any water larger than a pond or a

rivulet: and my surprise was mingled with no small fear when I was put into one

of these canoes, and we began to paddle and move along the river. We continued

going on thus till night; and when we came to land, and made fires on the banks,

each family by themselves some dragged their canoes on shore, others stayed and

cooked in theirs, and laid in them all night. Those on the land had mats, of

which they made tents, some in the shape of little houses: in these we slept and

after the morning meal we embarked again and proceeded as before. I was often

very much astonished to see some of the women, as well as the men, jump into the

water, dive to the bottom, come up again, and swim about.

[ch. 2, par. 15a] Thus I continued to travel, sometimes by land, sometimes

by water, through different countries and various nations, till, at the end of

six or seven months after I had been kidnapped, I arrived at the sea coast. It

would be tedious and uninteresting to relate all the incidents which befell me

during this journey, and which I have not yet forgotten; of the various hands I

passed through, and the manners and customs of all the different people among

whom I lived: . . .

[ch. 2, par. 16] The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on

the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and

waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon

converted into terror when I was carried on board. I was immediately

handled and

tossed up to see if I were found by some of the crew; and

I was now persuaded

that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill

me. Their complexions too differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the

language they spoke (which was very different from any I had ever heard), united

to confirm me in this belief. Indeed such were the horrors of my views and fears

at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own I would have freely

parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest

slave in my own country. [note reversal of Western

racial color code; white

complexions = bad spirits]

[ch. 2, par. 17] When I looked round the ship too

and saw a large furnace or copper boiling, and

a multitude of black people of

every description chained together, everyone of their countenances expressing

dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and quite overpowered with

horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered

a little I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those

who brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in

order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by

those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and loose hair. They told me I

was not; and one of the crew brought me a small portion of spirituous liquor in

a wine glass; but, being afraid of him, I would not take it out of his hand. One

of the blacks therefore took it from him and gave it to me, and I took a little

down my palate, which, instead of reviving me, as they thought it would, threw

me into the greatest consternation at the strange feeling it produced having

never tasted any such liquor before. Soon after this the blacks who brought me

on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.

[ch. 2, par. 18] I now saw myself deprived of all chance of returning to

my native country, or even the least glimpse of hope of gaining the shore which

I now considered as friendly; and I even wished for my former slavery in

preference to my present situation, which was filled with horrors of every kind,

still heightened by my ignorance of what I was to undergo. I was not long

suffered to indulge my grief; I was soon put down hinder

[under] the decks, and there I

received such a salutation in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life:

so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench and crying together, I became so

sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste

anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to

my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and on my refusing to eat,

one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across I think the windlass

and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. I had never experienced

anything of this kind before; and although, not being used to the water, I

naturally feared that element the first time I saw it, yet nevertheless, could I

have got over the nettings, I would have jumped over the side, but I could not;

and, besides, the crew used to watch us very closely who were not chained down

to the decks, lest we should leap into the water: and I have seen some of these

poor African prisoners most severely cut for attempting to do so, and hourly

whipped for not eating. This indeed was often the case with myself. In a little

time after, amongst the poor chained men, I found some of my own nation, which

in a small degree gave ease to my mind. I inquired of these what was to be done

with us; they gave me to understand we were to be carried to these white

people's country to work for them.

[ch. 2, par. 19] I then was a little revived, and thought, if it were no

worse than working, my situation was not so desperate: but still I feared I

should be put to death, the white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so

savage a manner; for I had never seen among any people such instances of brutal

cruelty; and this not only shown towards us blacks, but also to some of the

whites themselves. One white man in particular I saw, when we were permitted to

be on deck, flogged so unmercifully with a large rope near the foremast that he

died in consequence of it; and they tossed him over the side as they would have

done a brute. This made me fear these people the more; and I expected nothing

less than to be treated in the same manner. I could not help expressing my fears

and apprehensions to some of my countrymen: I asked them if these people had no

country, but lived in this hollow place (the ship): they told me they did not,

but came from a distant one. 'Then,' said I, 'how comes it in all our country we

never heard of them?' They told me because they lived so very far off. I then

asked where were their women? had they any like themselves? I was told they had:

'and why,' said I, 'do we not see them?' They answered, because they were left

behind. I asked how the vessel could go? They told me they could not tell; but

that there were cloths put upon the masts by the help of the ropes I saw, and

then the vessel went on; and the white men had some spell or magic they put in

the water when they liked in order to stop the vessel. I was exceedingly amazed

at this account, and really thought they were spirits. I therefore wished much

to be from amongst them, for I expected they would sacrifice me: but my wishes

were vain; for we were so quartered that it was impossible for any of us to make

our escape.

[ch. 2, par. 20] While we stayed on the coast I was mostly on deck; and

one day, to my great astonishment, I saw one of these vessels coming in with the

sails up. As soon as the whites saw it, they gave a great shout, at which we

were amazed; and the more so as the vessel appeared larger by approaching

nearer. At last she came to an anchor in my sight, and when the anchor was let

go I and my countrymen who saw it were lost in astonishment to observe the

vessel stop; and were now convinced it was done by magic. Soon after this the

other ship got her boats out, and they came on board of us, and the people of

both ships seemed very glad to see each other. Several of the strangers also

shook hands with us black people, and made motions with their bands, signifying

I suppose we were to go to their country; but we did not understand them. At

last, when the ship we were in had got in all her cargo, they made ready with

many fearful noises, and we were all put under deck, so that we could not see

how they managed the vessel. But this disappointment was the least of my sorrow.

The stench of the hold while we were on the coast was so intolerably loathsome,

that it was dangerous to remain there for any time, and some of us had been

permitted to stay on the deck for the fresh air; but now that the whole ship's

cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential. The closeness

of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship,

which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost

suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so that the air soon became

unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and

brought on a

sickness among the slaves, of which many died, thus falling victims to the

improvident avarice, as I may call it, of their purchasers.

[ch. 2, par. 21] This wretched situation was again

aggravated by the galling of the chains, now become insupportable; and the filth

of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost

suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the

whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable. Happily perhaps for myself I was

soon reduced so low here that it was thought necessary to keep me almost always

on deck; and from my extreme youth I was not put in fetters. In this situation I

expected every hour to share the fate of my companions, some of whom were almost

daily brought upon deck at the point of death, which I began to hope would soon

put an end to my miseries. Often did I think many of the inhabitants of the deep

much more happy than myself. I envied them the freedom they enjoyed, and as

often wished I could change my condition for theirs.

[ch. 2, par. 21] Every circumstance I met with served only to render my

state more painful, and heighten my apprehensions, and my opinion of the cruelty

of the whites. One day they had taken a number of fishes and when they had

killed and satisfied themselves with as many as they thought fit, to our

astonishment who were on the deck, rather than give any of them to us to eat as

we expected, they tossed the remaining fish into the sea again, although we

begged and prayed for some as well as we could, but in vain; and some of my

countrymen, being pressed by hunger, took an opportunity, when they thought no

one saw them, of trying to get a little privately; but they were discovered, and

the attempt procured them some very severe floggings. One day, when we had a

smooth sea and moderate wind, two of my wearied countrymen who were chained

together (I was near them at the time), preferring death to such a life of

misery, somehow made through the nettings and

jumped into the sea: immediately

another quite dejected fellow, who, on account of his illness, was suffered to

be out of irons, also followed their example; and I believe many more would very

soon have done the same if they had not been prevented by the ship's crew, who

were instantly alarmed. Those of us that were the most active were in a moment

put down under the deck, and there was such a noise and confusion amongst the

people of the ship as I never heard before, to stop her, and get the boat out to

go after the slaves. However two of the wretches were drowned, but they got the

other, and afterwards flogged him unmercifully for thus attempting to prefer

death to slavery. . . .

Location of Barbados in Eastern Caribbean (see 2.27

below)

[ch. 2, par. 22] At last we came in sight of the island of

Barbadoes, at

which the whites on board gave a great shout, and made many signs of joy to us.

We did not know what to think of this; but as the vessel drew nearer we plainly

saw the harbor, and other ships of different kinds and sizes; and we soon

anchored amongst them off Bridge Town. Many merchants and planters now came on

board, though it was in the evening. They put us in separate parcels, and

examined us attentively. They also made us jump, and pointed to the land,

signifying we were to go there. We thought by this we should be eaten by those

ugly men, as they appeared to us; and, when soon after we were all put down

under the deck again, there was much dread and trembling among us, and nothing

but bitter cries to be heard all the night from these apprehensions, insomuch

that at last the white people got some old slaves from the land to pacify us.

They told us we were not to be eaten, but to work, and were soon to go on land,

where we should see many of our country people. This report eased us much; and

sure enough, soon after we were landed, there came to us

Africans of all

languages. We were conducted immediately to the merchant's yard, where we were

all pent up together like so many sheep in a fold, without regard to sex or age.

[ch. 2, par. 23] As every object was new to me everything I saw filled me

with surprise. What struck me first was that the houses were built with stories,

and in every other respect different from those in Africa: but I was still more

astonished on seeing people on horseback. I did not know what this could mean;

and indeed I thought these people were full of nothing but magical arts. While I

was in this astonishment one of my fellow prisoners spoke to a countryman of his

about the horses, who said they were the same kind they had in their country. I

understood them, though they were from a distant part of Africa, and I thought

it odd I had not seen any horses there; but afterwards when I came to converse

with different Africans, I found they had many horses amongst them, and much

larger than those I then saw. We were not many days in the merchant's custody

before we were sold after their usual manner, which is this: On a signal given

(as the beat of a drum), the buyers rush at once into the yard where the slaves

are confined, and make choice of that parcel they like best. The noise and

clamor with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the

countenances of the buyers serve not a little to increase the apprehensions of

the terrified Africans, who may well be supposed to consider them as the

ministers of that destruction to which they think themselves devoted.

[ch. 2, par. 24] In this manner, without scruple, are relations and friends separated, most of them never to see each other again. I remember in the vessel in which I was brought over, in the men's apartment, there were several brothers, who, in the sale, were sold in different lots; and it was very moving on this occasion to see and hear their cries at parting. O, ye nominal Christians! might not an African ask you, learned you this from your God, who says unto you, Do unto all men as you would men should do unto you? Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends to toil for your luxury and lust of gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice? Are the dearest friends and relations, now rendered more dear by their separation from their kindred, still to be parted from each other, and thus prevented from cheering the gloom of slavery with the small comfort of being together and mingling their sufferings and sorrows? Why are parents to lose their children, brothers their sisters, or husbands their wives? Surely this is a new refinement in cruelty, which, while it has no advantage to atone for it, thus aggravates distress, and adds fresh horrors even to the wretchedness of slavery.

![]()

|

from Chapter 3 The author is carried to Virginia—His distress—Surprise at seeing a picture and a watch—. . . |

[ch. 3, par. 1] I now totally lost the small remains of comfort I had

enjoyed in conversing with my countrymen; the women too, who used to wash and

take care of me, were all gone different ways, and I never saw one of them

afterwards.

[ch. 3, par. 2] I stayed in this island

[Barbadoes] for a few days; I believe it

could not be above a fortnight; when I and some few more slaves, that were not

saleable amongst the rest, from very much fretting, were shipped off in a sloop

for North America. On the passage we were better treated than when we were

coming from Africa, and we had plenty of rice and fat pork. We were landed up a

river a good way from the sea, about Virginia county, where we saw few or none

of our native Africans, and not one soul who could talk to me. I was a few weeks

weeding grass, and gathering stones in a plantation; and at last all my

companions were distributed different ways, and only myself was left.

I was now

exceedingly miserable, and thought myself worse off than any of the rest of my

companions; for they could talk to each other, but I had no person to speak to

that I could understand. In this state I was constantly grieving and pining, and

wishing for death rather than anything else.

[ch. 3, par. 3] While I was in this plantation the gentleman, to whom I

suppose the estate belonged, being unwell, I was one day sent for to his

dwelling house to fan him; when I came into the room where he was I was very

much affrighted at some things I saw, and the more so as I had seen

a black

woman slave as I came through the house, who was cooking the dinner, and the

poor creature was cruelly loaded with various kinds of iron machines; she had

one particularly on her head, which locked her mouth so fast that she could

scarcely speak; and could not eat nor drink. I was much astonished and shocked

at this contrivance, which I afterward learned was called the iron muzzle. Soon

after I had a fan put into my hand, to fan the gentleman while he slept; and so

I did indeed with great fear.

[ch. 3, par. 4] While he was fast asleep I indulged

myself a great deal in looking about the room, which to me appeared very fine

and curious. The first object that engaged my attention was a watch which hung

on the chimney, and was going. I was quite surprised at the noise it made and

was afraid it would tell the gentleman anything I might do amiss

[wrong]: and when I

immediately after observed a picture hanging in the room, which appeared

constantly to look at me, I was still more affrighted, having never

seen such things as these before. At one time I thought it was something

relative to magic; and not seeing it move I thought it

might be some way the whites had to keep their great men when they died,

and offer them libation [offerings]

as we used to do to our friendly spirits. In this state of anxiety I remained

till my master awoke, when I was dismissed out of the room, to my no small

satisfaction and relief; for I thought that these people were all made up of

wonders. In this place I was called Jacob; but on board the African snow

I was called Michael.

[ch. 3, par. 5] I had been some time in this miserable, forlorn, and much

dejected state, without having anyone to talk to, which made my life a burden,

when the kind and unknown hand of the Creator (who in very deed leads the blind

in a way they know not) now began to appear, to my comfort; for one day the

captain of a merchant ship, called the Industrious Bee, came on some business to

my master's house. This gentleman, whose name was Michael Henry Pascal, was a

lieutenant in the royal navy, but now commanded this trading ship, which was

somewhere in the confines of the county many miles off.

[ch. 3, par. 6] While he was at my master's house

it happened that he saw me, and liked me so well that he made a purchase of me.

I think I have often heard him say he gave thirty or forty pounds sterling for

me; but I do not now remember which. However, he meant me for a present to some

of his friends in England: and I was sent accordingly from the house of my then

master, one Mr. Campbell, to the place where the ship lay; I was conducted on

horseback by an elderly black man (a mode of travelling which appeared very odd

to me). When I arrived I was carried on board a fine large ship, loaded with

tobacco, etc. and just ready to sail for England. I now thought my condition

much mended; I had sails to lie on, and plenty of good vitals

[foodstuffs] to eat; and

everybody on board used me very kindly, quite contrary to what I had seen of any

white people before; I therefore began to think that they were not all of the

same disposition. A few days after I was on board we sailed for England.

[ch. 3, par. 7] I was still at a loss to conjecture my destiny. By this

time, however, I could smatter a little imperfect English; and I wanted to know

as well as I could where we were going. Some of the people of the ship used to

tell me they were going to carry me back to my own country, and this made me

very happy. I was quite rejoiced at the sound of going back; and thought if I

should get home what wonders I should have to tell. But I was reserved for

another fate, and was soon undeceived when we came within sight of the

English coast. While I was on board this ship, my captain and master named me

Gustavus Vassa. I at that time began to understand him a little, and refused to

be called so, and told him as well as I could that I would be called Jacob; but

he said I should not, and still called me Gustavus; and when I refused to answer

to my new name, which at first I did, it gained me many a cuff

[fisticuff]; so at length I

submitted, and was obliged to bear the present name, by which I have been known

ever since. . . .

[ch. 3, par.8] There was on board the ship a young lad who had never been at sea before, about four or five years older than myself: his name was Richard Baker. He was a native of America, had received an excellent education, and was of a most amiable temper. Soon after I went on board he showed me a great deal of partiality and attention, and in return I grew extremely fond of him. We at length became inseparable; and, for the space of two years, he was of very great use to me, and was my constant companion and instructor. Although this dear youth had many slaves of his own, yet he and I have gone through many sufferings together on shipboard; and we have many nights lain in each other's bosoms when we were in great distress. Thus such a friendship was cemented between us as we cherished till his death, which, to my very great sorrow, happened in the year 1759, when he was up the Archipelago, on board his majesty's ship the Preston: an event which I have never ceased to regret, as I lost at once a kind interpreter, an agreeable companion, and a faithful friend; who, at the age of fifteen, discovered a mind superior to prejudice; and who was not ashamed to notice, to associate with, and to be the friend and instructor of one who was ignorant, a stranger, of a different complexion, and a slave! . . .

[ch. 3, par. 9] However, all my alarms began to subside when we got sight of land; and at last the ship arrived at Falmouth, after a passage of thirteen weeks. Every heart on board seemed gladdened on our reaching the shore, and none more than mine. The captain immediately went on shore, and sent on board some fresh provisions, which we wanted very much: we made good use of them, and our famine was soon turned into feasting, almost without ending. It was about the beginning of the spring 1757 when I arrived in England; and I was nearly twelve years of age at that time. I was very much struck with the buildings and the pavement of the streets in Falmouth; and, indeed, any object I saw filled me with new surprise.

[ch. 3, par. 10] One morning when I got upon deck, I saw it covered all over with the snow that fell overnight: as I had never seen any thing of the kind before, I thought it was salt; so I immediately ran down to the mate and desired him, as well as I could, to come and see how somebody in the night had thrown salt all over the deck. He, knowing what it was, desired me to bring some of it down to him: accordingly I took up a handful of it, which I found very cold indeed; and when I brought it to him he desired me to taste it. I did so, and I was surprised beyond measure. I then asked him what it was; he told me it was snow: but I could not in anywise understand him. He asked me if we had no such thing in my country; and I told him, No. I then asked him the use of it, and who made it; he told me a great man in the heavens, called God: but here again I was to all intents and purposes at a loss to understand him; and the more so, when a little after I saw the air filled with it, in a heavy shower, which fell down on the same day.

[ch. 3, par. 11] After this

I went to church; and

having never been at such a place before, I was again amazed at seeing and

hearing the service I asked all I could about it; and they gave me to understand

it was worshipping God, who made us and all things. I was still at a great loss,

and soon got into an endless field of inquiries, as well as I was able to speak

and ask about things. However, my little friend Dick used to be my best

interpreter; for I could make free with him, and he always instructed me with

pleasure: and from what I could understand by him of this God, and in seeing

these white people did not fell one another, as we did, I was much pleased; and

in this I thought they were much happier than we Africans. I was astonished at

the wisdom of the white people in all things I saw; but was amazed at their not

sacrificing, or making any offerings, and eating with unwashed hands, and

touching the dead. I likewise could not help remarking the particular

slenderness of their women, which I did not at first like; and I thought they

were not so modest and shamefaced as the African women.

[ch. 3, par. 12] I had often seen my master and Dick

employed in reading;

and I had a great curiosity to talk to the books, as I thought they did; and so

to learn how all things had a beginning: for that purpose I have often taken up

a book, and have talked to it, and then put my ears to it, when alone, in hopes

it would answer me; and I have been very much concerned when I found it remained

silent.

[ch. 3, par. 13] My master lodged at the house of a gentleman in Falmouth, who had a fine little daughter about six or seven years of age, and she grew prodigiously fond of me; insomuch that we used to eat together, and had servants to wait on us. I was so much caressed [pampered] by this family that it often reminded me of the treatment I had received from my little noble African master. After I had been here a few days, I was sent on board of the ship; but the child cried so much after me that nothing could pacify her till I was sent for again. It is ludicrous enough, that I began to fear I should be betrothed to this young lady; and when my master asked me if I would stay there with her behind him, as he was going away with the ship, which had taken in the tobacco again, I cried immediately, and said I would not leave her. At last, by stealth, one night I was sent on board the ship again; and in a little time we sailed for Guernsey, where she was in part owned by a merchant, one Nicholas Doberry.

[ch. 3, par. 14] As I was now

amongst a people who

had not their faces scarred, like some of the African nations where I had been,

I was very glad I did not let them ornament me in that manner when I was with

them. When we arrived at Guernsey, my master placed me to board and lodge with

one of his mates, who had a wife and family there; and some months afterwards he

went to England, and left me in care of this mate, together with my friend Dick:

This mate had a little daughter, aged about five or six years, with whom I used

to be much delighted.

[ch. 3, par. 15] I had often observed that when her mother washed her

face it looked very rosy; but when she washed mine it did not look so: I

therefore tried often times myself if I could not by washing make my face of the

same colour as my little playmate (Mary), but it was all in vain; and I now

began to be mortified at the difference in our complexions. This woman behaved

to me with great kindness and attention; and taught me everything in the same

manner as she did her own child, and indeed in every respect treated me as such.

I remained here till the summer of the year 1757; when my master, being

appointed first lieutenant of his majesty's ship the Roebuck, sent for Dick and

me, and his old mate: on this we all left Guernsey, and set out for England in a

sloop bound for London. . . .

![]()

|

from CHAP. IV |

[4.1] . . . I have often reflected with surprise that I never felt half the alarm at any of the numerous dangers I have been in, that I was filled with at the first sight of the Europeans . . . . That fear, however, which was the effect of my ignorance, wore away as I began to know them. I could now speak English tolerably well, and I perfectly understood every thing that was said. I now not only felt myself quite easy with these new countrymen, but relished their society and manners. I no longer looked upon them as spirits, but as men superior to us; and therefore I had the stronger desire to resemble them; to imbibe their spirit, and imitate their manners; I therefore embraced every occasion of improvement; and every new thing that I observed I treasured up in my memory. I had long wished to be able to read and write; and for this purpose I took every opportunity to gain instruction, but had made as yet very little progress. However, when I went to London with my master, I had soon an opportunity of improving myself, which I gladly embraced. Shortly after my arrival, he sent me to wait upon the Miss Guerins, who had treated me with much kindness when I was there before; and they sent me to school.

[4.2] While I was attending these ladies their servants told me I could not go to Heaven unless I was baptized. This made me very uneasy; for I had now some faint idea of a future state: accordingly I communicated my anxiety to the eldest Miss Guerin, with whom I was become a favourite, and pressed her to have me baptized; when to my great joy she told me I should. She had formerly asked my master to let me be baptized, but he had refused; however she now insisted on it; and he being under some obligation to her brother complied with her request; so I was baptized in St. Margaret's church, Westminster, in February 1759, by my present name. The clergyman, at the same time, gave me a book, called a Guide to the Indians, written by the Bishop of Sodor and Man. On this occasion Miss Guerin did me the honour to stand as godmother . . .

[4.3] The Namur* being again got ready for sea, my master, with his gang, was ordered on board; and, to my no small grief, I was obliged to leave my school-master, whom I liked very much, and always attended while I stayed in London, to repair on board with my master. Nor did I leave my kind patronesses, the Miss Guerins, without uneasiness and regret. They often used to teach me to read, and took great pains to instruct me in the principles of religion and the knowledge of God. I therefore parted from those amiable ladies with reluctance; after receiving from them many friendly cautions how to conduct myself, and some valuable presents. [Namur = name of ship, possibly named for Belgian city of Namur; probably unrelated to Prince Namor the Sub-Mariner of Marvel Comics]

[4.2] When I came to Spithead, I found we were destined for the Mediterranean . . . .

|

|

|

[4.3] I had frequently told several people, in my excursions on shore, the story of my being kidnapped with my sister, and of our being separated, as I have related before; and I had as often expressed my anxiety for her fate, and my sorrow at having never met her again. One day, when I was on shore, and mentioning these circumstances to some persons, one of them told me he knew where my sister was, and, if I would accompany him, he would bring me to her. Improbable as this story was I believed it immediately, and agreed to go with him, while my heart leaped for joy: and, indeed, he conducted me to a black young woman, who was so like my sister, that, at first sight, I really thought it was her: but I was quickly undeceived; and, on talking to her, I found her to be of another nation. . . .

[4.4] While we lay here the Preston came in from the Levant [Mediterranean]. As soon as she arrived, my master told me I should now see my old companion, Dick, who had gone in her when she sailed for Turkey. I was much rejoiced at this news, and expected every minute to embrace him; and when the captain came on board of our ship, which he did immediately after, I ran to inquire after my friend; but, with inexpressible sorrow, I learned from the boat's crew that the dear youth was dead! and that they had brought his chest, and all his other things, to my master: these he afterwards gave to me, and I regarded them as a memorial of my friend, whom I loved, and grieved for, as a brother. . . . [more naval tours and engagements follow;] . . .

[4.5] After our ship was fitted out again for service, in September [1762; Olaudah is about 17] she went to Guernsey, where I was very glad to see my old hostess, who was now a widow, and my former little charming companion, her daughter. I spent some time here very happily with them, till October, when we had orders to repair to Portsmouth. We parted from each other with a great deal of affection; and I promised to return soon, and see them again, not knowing what all-powerful fate had determined for me. Our ship having arrived at Portsmouth, we went into the harbour . . . I thought now of nothing but being freed, and working for myself, and thereby getting money to enable me to get a good education; for I always had a great desire to be able at least to read and write; and while I was on shipboard I had endeavoured to improve myself in both. While I was in the Ætna particularly, the captain's clerk taught me to write, and gave me a smattering of arithmetic as far as the rule of three. There was also one Daniel Queen, about forty years of age, a man very well educated, who messed [ate meals] with me on board this ship, and he likewise dressed and attended the captain. Fortunately this man soon became very much attached to me, and took very great pains to instruct me in many things. He taught me to shave and dress hair a little [barber’s trade was often a niche market for Africans in Europe and America], and also to read in the Bible, explaining many passages to me, which I did not comprehend. I was wonderfully surprised to see the laws and rules of my country written almost exactly here; a circumstance which I believe tended to impress our manners and customs more deeply on my memory. I used to tell him of this resemblance; and many a time we have sat up the whole night together at this employment. In short, he was like a father to me; and some even used to call me after his name; they also styled me the black Christian. Indeed I almost loved him with the affection of a son. . . . He used to say, that he and I never should part; and that when our ship was paid off, as I was as free as himself or any other man on board, he would instruct me in his business, by which I might gain a good livelihood. This gave me new life and spirits; and my heart burned within me, while I thought the time long till I obtained my freedom. For though my master had not promised it to me, yet, besides the assurances I had received that he had no right to detain me, he always treated me with the greatest kindness, and reposed in me an unbounded confidence; he even paid attention to my morals; and would never suffer me to deceive him, or tell lies, of which he used to tell me the consequences; and that if I did so God would not love me; so that, from all this tenderness, I had never once supposed, in all my dreams of freedom, that he would think of detaining me any longer than I wished.

[4.6] In pursuance of our orders we sailed from Portsmouth for the Thames . . . [A]ll in an instant, without having before given me the least reason to suspect any thing of the matter, he [Equiano’s master] forced me into the barge; saying, I was going to leave him, but he would take care I should not. I was so struck with the unexpectedness of this proceeding, that for some time I did not make a reply, only I made an offer to go for my books and chest of clothes, but he swore I should not move out of his sight; and if I did he would cut my throat, at the same time taking his hanger [knife]. I began, however, to collect myself; and, plucking up courage, I told him I was free, and he could not by law serve me so. But this only enraged him the more; and he continued to swear, and said he would soon let me know whether he would or not, and at that instant sprung himself into the barge from the ship, to the astonishment and sorrow of all on board. The tide, rather unluckily for me, had just turned downward, so that we quickly fell down the river along with it, till we came among some outward-bound West Indiamen [sending OE to the West Indies or Caribbean with no rights to freedom]; for he was resolved to put me on board the first vessel he could get to receive me. The boat's crew, who pulled against their will, became quite faint different times, and would have gone ashore; but he would not let them. Some of them strove then to cheer me, and told me he could not sell me, and that they would stand by me, which revived me a little; and I still entertained hopes; for as they pulled along he asked some vessels to receive me, but they could not. But, just as we had got a little below Gravesend, we came alongside of a ship which was going away the next tide for the West Indies; her name was the Charming Sally, Captain James Doran; and my master went on board and agreed with him for me; and in a little time I was sent for into the cabin.

[4.6a] When I came there Captain Doran asked me if I knew him; I answered that I did not; 'Then,' said he 'you are now my slave.' I told him my master could not sell me to him, nor to any one else. 'Why,' said he, 'did not your master buy you?' I confessed he did. 'But I have served him,' said I, 'many years, and he has taken all my wages and prize-money, for I only got one sixpence during the war; besides this I have been baptized; and by the laws of the land no man has a right to sell me:' And I added, that I had heard a lawyer and others at different times tell my master so. They both then said that those people who told me so were not my friends; but I replied—it was very extraordinary that other people did not know the law as well as they.

[4.6b] Upon this Captain Doran said I talked too much English; and if I did not behave myself well, and be quiet, he had a method on board to make me. I was too well convinced of his power over me to doubt what he said; and my former sufferings in the slave-ship presenting themselves to my mind, the recollection of them made me shudder. However, before I retired I told them that as I could not get any right among men here I hoped I should hereafter in Heaven; and I immediately left the cabin, filled with resentment and sorrow. The only coat I had with me my master took away with him, and said if my prize-money had been 10,000 £. he had a right to it all, and would have taken it. I had about nine guineas, which, during my long sea-faring life, I had scraped together from trifling perquisites and little ventures; and I hid it that instant, lest my master should take that from me likewise, still hoping that by some means or other I should make my escape to the shore; and indeed some of my old shipmates told me not to despair, for they would get me back again; and that, as soon as they could get their pay, they would immediately come to Portsmouth to me, where this ship was going: but, alas! all my hopes were baffled, and the hour of my deliverance was yet far off. My master, having soon concluded his bargain with the captain, came out of the cabin, and he and his people got into the boat and put off; I followed them with aching eyes as long as I could, and when they were out of sight I threw myself on the deck, while my heart was ready to burst with sorrow and anguish.

|

from CHAP. V. [1763-66, mostly in Caribbean] |

[5.1] Thus, at the moment I expected all my toils to end, was I plunged, as I supposed, in a new slavery; in comparison of which all my service hitherto had been 'perfect freedom;' and whose horrors, always present to my mind, now rushed on it with tenfold aggravation. I wept very bitterly for some time: and began to think that I must have done something to displease the Lord, that he thus punished me so severely. . . . In a little time my grief, spent with its own violence, began to subside; and after the first confusion of my thoughts was over I reflected with more calmness on my present condition: I considered that trials and disappointments are sometimes for our good, and I thought God might perhaps have permitted this in order to teach me wisdom and resignation; for he had hitherto shadowed me with the wings of his mercy, and by his invisible but powerful hand brought me the way I knew not. These reflections gave me a little comfort, and I rose at last from the deck with dejection and sorrow in my countenance, yet mixed with some faint hope that the Lord would appear for my deliverance.

[5.2] Soon afterwards, as my new master was going ashore, he called me to him, and told me to behave myself well, and do the business of the ship the same as any of the rest of the boys, and that I should fare the better for it; but I made him no answer. I was then asked if I could swim [to freedom on the English shore], and I said, No. However I was made to go under the deck, and was well watched. The next tide the ship got under way . . .

[5.3] On the 13th of February 1763, from the mast-head, we descried our destined island Montserrat [island, British territory in Lesser Antilles of Caribbean]; and soon after I beheld those

"Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace /

And rest can rarely dwell. Hope never comes /

That comes to all, but torture without end

Still urges."

Montserrat in Lesser Antilles of Caribbean Sea

[5.4] At the sight of this land of bondage, a fresh horror ran through all my frame, and chilled me to the heart. My former slavery now rose in dreadful review to my mind, and displayed nothing but misery, stripes [whipping], and chains . . . I now knew what it was to work hard; I was made to help to unload and load the ship. And, to comfort me in my distress in that time, two of the sailors robbed me of all my money, and ran away from the ship. I had been so long used to an European climate that at first I felt the scorching West India sun very painful . . . . The captain then told me my former master had sent me there to be sold; but that he had desired him to get me the best master he could, as he told him I was a very deserving boy. . . .

[5.5] Mr. [Robert] King, my new master, then made a reply, and said the reason he had bought me was on account of my good character; and, as he had not the least doubt of my good behaviour, I should be very well off with him. He also told me he did not live in the West Indies, but at Philadelphia, where he was going soon; and, as I understood something of the rules of arithmetic, when we got there he would put me to school, and fit me for a clerk. This conversation relieved my mind a little, and I left those gentlemen considerably more at ease in myself than when I came to them; and I was very grateful to Captain Doran, and even to my old master, for the character [reference] they had given me; a character which I afterwards found of infinite service to me. I went on board again, and took leave of all my shipmates; and the next day the ship sailed. . . . [I]f my new master had not been kind to me I believe I should have died under it at last. And indeed I soon found that he [Mr. King, his new master, a leading merchant from Philadelphia] fully deserved the good character which Captain Doran had given me of him; for he possessed a most amiable disposition and temper, and was very charitable and humane. If any of his slaves behaved amiss he did not beat or use them ill, but parted with them. This made them afraid of disobliging him; and as he treated his slaves better than any other man on the island, so he was better and more faithfully served by them in return. [This theme becomes an important element of Equiano’s ideas for reform, bearing less on abolition of slavery than that a humane spirit achieves its ends better] . . .

[5.6] Mr. King soon asked me what I could do; and at the same time said he did not mean to treat me as a common slave. I told him I knew something of seamanship, and could shave and dress hair pretty well; and I could refine wines, which I had learned on shipboard, where I had often done it; and that I could write, and understood arithmetic tolerably well as far as the Rule of Three. He then asked me if I knew any thing of gauging [measuring]; and, on my answering that I did not, he said one of his clerks should teach me to gauge.

[5.7] Mr. King dealt in all manner of merchandise, and kept from one to six clerks. He loaded many vessels in a year; particularly to Philadelphia, where he was born, and was connected with a great mercantile [trading] house in that city. He had besides many vessels . . . of different sizes, which used to go about the island; and others to collect rum, sugar, and other goods. I understood pulling and managing those boats very well; and this hard work, which was the first that he set me to, in the sugar seasons used to be my constant employment. I have rowed the boat, and slaved at the oars, from one hour to sixteen in the twenty-four; during which I had fifteen pence sterling per day to live on, though sometimes only ten pence. . . . From being thus employed, during the time I served Mr. King, in going about the different estates on the island, I had all the opportunity I could wish for to see the dreadful usage of the poor men; usage that reconciled me to my situation, and made me bless God for the hands into which I had fallen.

[5.8] I have sometimes heard it asserted that a negro cannot earn his master the first cost; but nothing can be further from the truth. . . . But surely this assertion refutes itself; for, if it be true, why do the planters and merchants pay such a price for slaves? And, above all, why do those who make this assertion exclaim the most loudly against the abolition of the slave trade? So much are men blinded, and to such inconsistent arguments are they driven by mistaken interest! . . .