|

Craig White's Literature Courses

Romanticism or

the Romantic Period, Movement, Style, & Spirit |

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) Wanderer Above the Fog (1818) |

"Romanticism" is a period, movement, style, or genre in literature, music, and other arts starting in the late 1700s and flourishing through the early to mid 1800s, a time when the modern mass culture in which we now live first took form following the establishment of modern social systems during the Enlightenment or Age of Reason:

![]() the rise of nation-states as defining social and geographic entities

the rise of nation-states as defining social and geographic entities

![]() increasing

geographic and social mobility, with more people moving to cities

& the growth of a literate middle class,

increasing

geographic and social mobility, with more people moving to cities

& the growth of a literate middle class,

![]() new technologies

dependent on power from fossil fuels (trains, steamships,

industrial printing)

new technologies

dependent on power from fossil fuels (trains, steamships,

industrial printing)

![]() longer life-spans and rising standards of living enable ideas or values

including individualism, imagination. idealization of

childhood, families, love, nature, and the past.

longer life-spans and rising standards of living enable ideas or values

including individualism, imagination. idealization of

childhood, families, love, nature, and the past.

The Romantic era rises from the new wealth, stability, and sense of progress created by the preceding Enlightenment. Romanticism thus depends heavily on the practical accomplishments of the prior un-Romantic era, even while distancing itself from the mechanical or systematic associations of the Age of Reason—a relationship between material wealth and scientific-technological knowledge on one hand, and personal, spiritual, or emotional transcendence on the other, that twenty-first century Americans continue to manage.

Thus Romanticism is the historical period of literature in which modern readers most begin to see a reflection of themselves and their own modern conflicts and desires.

The

Romantic period has passed, but its styles

and values still thrive today

in popular forms and familiar attitudes, e.g.:

![]() feelings, emotions,

and imagination take priority over logic and facts ("Anything you want you can have

if you only want it enough." cf. romance narrative)

feelings, emotions,

and imagination take priority over logic and facts ("Anything you want you can have

if you only want it enough." cf. romance narrative)

![]() belief in

children's innocence

and wisdom; youth as a golden age; adulthood as corruption and betrayal

belief in

children's innocence

and wisdom; youth as a golden age; adulthood as corruption and betrayal

![]() nature as beauty

and truth, esp. the sense of nature as the sublime (god-like

awesomeness mixing ecstatic pleasure mixed with pain, beauty mixed with terror)

nature as beauty

and truth, esp. the sense of nature as the sublime (god-like

awesomeness mixing ecstatic pleasure mixed with pain, beauty mixed with terror)

![]() heroic individualism;

the individual separate from the masses

heroic individualism;

the individual separate from the masses

![]() "outsiders" as representatives of special worth excluded by rigid

societies or irrational norms

"outsiders" as representatives of special worth excluded by rigid

societies or irrational norms

![]() nostalgia for

the past

nostalgia for

the past

![]() desire or will as personal motivation

desire or will as personal motivation

![]() intensification, excess, and extremes (see Romantic

rhetoric)

intensification, excess, and extremes (see Romantic

rhetoric)

![]() common people

idealized as

dependable source of true common sense and sentiment

common people

idealized as

dependable source of true common sense and sentiment

![]() idealized

or abstract settings; characters

as symbolic types

idealized

or abstract settings; characters

as symbolic types

![]() the

gothic as nightmare world of intense emotions and

complex psychology

the

gothic as nightmare world of intense emotions and

complex psychology

Any of these qualities may be associated with Romanticism, but none of them defines or limits Romanticism absolutely. Some of them even contradict each other.

Think of Romanticism as an "umbrella term" under which many stylistic themes and values meet and interact; e.g. the gothic, the sublime, the sentimental, love of nature, the romance narrative. (Most popular films today are romance narratives with simple Romantic characters (dashing young heroes, sweet but independent damsels, ugly corporate or state villains) operating by codes of chivalry and honor.)

The simplest for what is Romantic is "anything but the here and now" or whatever isn't Realistic—details below. (The Realistic, on the other hand, is the here and now, in all its complicated detail.)

![]()

Romanticism as literary, artistic, or personal style

Romantic emotion often has an inner-outer orientation: the inner self and nature way out there (separate from everyday society).

![]() One's inmost soul or self is touched by the beauty of

nature, or reaches out to

that beauty in the country, the mountains, the stars.

One's inmost soul or self is touched by the beauty of

nature, or reaches out to

that beauty in the country, the mountains, the stars.

![]() The inner and outer

correspond to each other: for instance, a dark and stormy night

reflects a tormented self or soul, or a gentle meadow with birds

chirping awakens an inner sense of peace or harmony.

The inner and outer

correspond to each other: for instance, a dark and stormy night

reflects a tormented self or soul, or a gentle meadow with birds

chirping awakens an inner sense of peace or harmony.

![]() Meanwhile, the

normal society immediately surrounding one's self—e.g., this

classroom, your workplace, the parking lot, the mall, our government and economy—is

reality, the here and now, which

cannot be

romanticized. (You can't want or desire

what you already have.)

Meanwhile, the

normal society immediately surrounding one's self—e.g., this

classroom, your workplace, the parking lot, the mall, our government and economy—is

reality, the here and now, which

cannot be

romanticized. (You can't want or desire

what you already have.)

![]() Instead of the here and now of drab reality, Romanticism values something

exotic, unattainable, or lost, an alternate reality that challenges the

everyday.

Instead of the here and now of drab reality, Romanticism values something

exotic, unattainable, or lost, an alternate reality that challenges the

everyday.

![]() For example, a nostalgic past or dramatic future, a distant star or a

voice deep inside, a dream desired, denied, but never forgotten . . . .

For example, a nostalgic past or dramatic future, a distant star or a

voice deep inside, a dream desired, denied, but never forgotten . . . .

Modern audiences are conversant with such Romantic themes or images. The term "Romantic" is commonly limited to love (just as "romances" now mean love stories), but some subtler uses reveal how the wider meaning of Romanticism endures:

"How romantic!" . . . "S/he's a romantic . . . ": such expressions do not exclude love, but their wider reference may not involve personal relationships. For example, "How romantic!" may describe a memory or a dream of a far-away beach in the moonlight.

"She or he's a romantic" implies a contrast with "s/he's a realist," affirming the disassociation of Romanticism from reality or realism.

| category of comparison | Romanticism | Realism |

|

historical period & political economics: |

1820-60; "Era of the Common Man"; Abolition; early women's movement |

1865-1910; Industrialization, Urbanization, Gilded Age; Reconstruction and Reaction |

| human form: | heroic individualism | social relations |

|

human motivation: |

honor, love, ideals |

survival of fittest; greed, lust, confusion |

|

setting: |

sublime frontier or gothic past |

growing cities; social class limits |

|

literary styles: |

elevated language |

dirty details |

![]()

Cultural History of Romanticism

Historically, the Romantic era is sometimes called "The Age of Revolution" from the French Revolution (1789-99) and the American Revolution (1775-83), the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and subsequent revolutions in Europe and Latin America (including the War for Mexican Independence, 1811-21).

The Romantic "Age of Revolution" may also refer to . . .

![]() liberating changes in the arts

(in literature, for instance, increasing use of everyday language, free

verse, appeals to common human feelings or emotions); and

liberating changes in the arts

(in literature, for instance, increasing use of everyday language, free

verse, appeals to common human feelings or emotions); and

![]() profound social and cultural changes that

radically transformed

everyday life—urbanization, early industrialization, movements for

equality, expanding markets and wealth for increasing numbers of people following the

Enlightenment's

institutionalization of constitutional government, freemarket economics, and

advances in science, medicine, hygiene and nutrition.

profound social and cultural changes that

radically transformed

everyday life—urbanization, early industrialization, movements for

equality, expanding markets and wealth for increasing numbers of people following the

Enlightenment's

institutionalization of constitutional government, freemarket economics, and

advances in science, medicine, hygiene and nutrition.

Historically, it is traditional to regard Romanticism as a reaction against the Enlightenment or Age of Reasont, but Romanticism depends on Enlightenment institutions and practices for support and continuity.

Stylistically, Romanticism includes movements or terms as diverse but associated as the gothic, the sublime, Transcendentalism, and the romance narrative, and the significance of feelings and the imagination over (or in addition to) Enlightenment values like reason, empiricism, and logic.

The Romantic movement began in Europe, particularly Germany, but became an international movement and style dominant throughout Europe, in Russia, the Americas, and beyond.

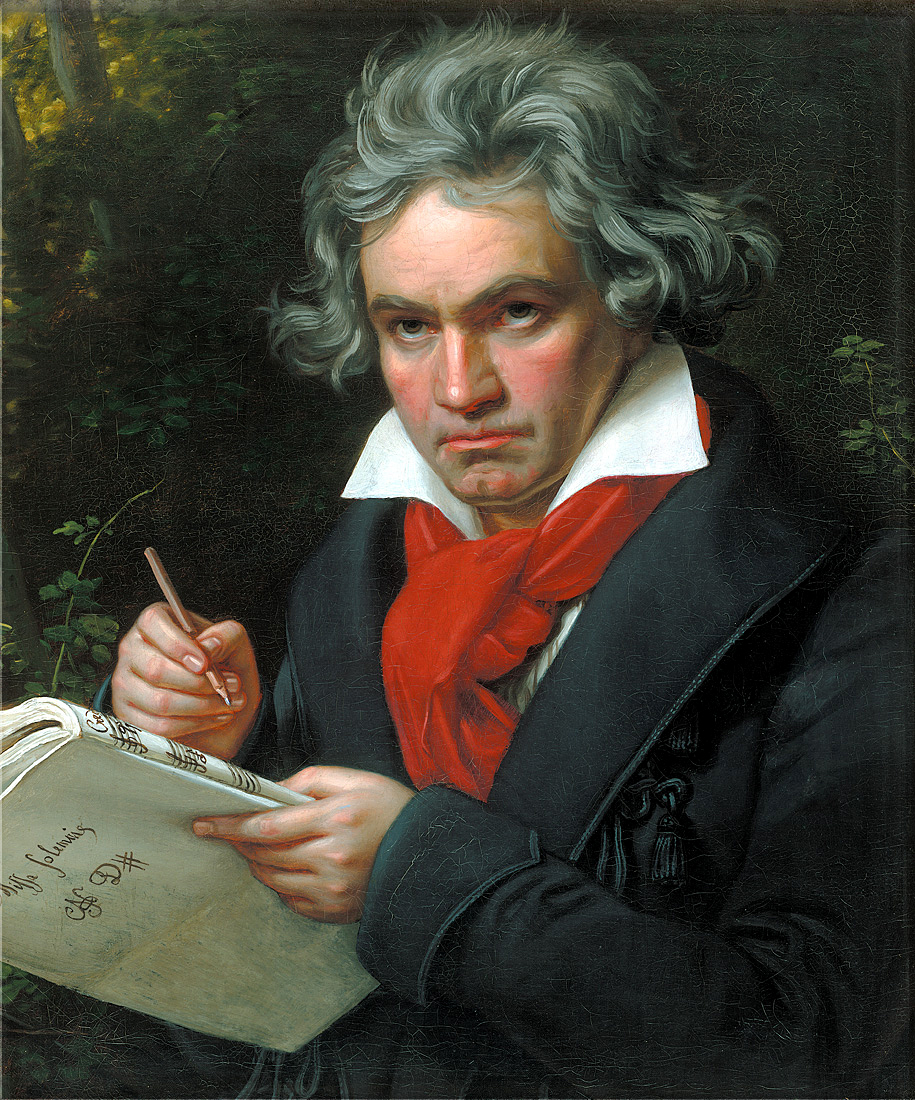

A simple, memorable way to imagine the Romantic era: an age of "heroic individuals" whose styles and subjects symbolized the power of the human will or spirit in shaping history and art.

Titanic Figures of the Romantic Era

|

|

|

Lord Byron in Albanian Dress (1813) by Thomas Phillips Byron (1788-1824), prototype for Romantic Byronic Hero died near Albania while working for Greek Independence from Turkey |

Mary Shelley (1797-1851), author of Frankenstein (1818) portrait by Reginald Easton, 1857 |

Romantic spirit or style (developed in but not limited to the Romantic era)

In everyday modern English, "Romantic" commonly refers to feelings of love, desire, or escape and "romance" is used to describe a love story ("a woman's romance").

"Romantic" may also be applied to an attractively exotic person or situation ("He's so romantic!" . . . "Oh, that's romantic!")

For literature and the arts, "Romantic" has a broader meaning that does not necessarily conflict with popular usage—but the literary or historical meaning is more extensive and adaptable.

This larger meaning (NOT LIMITED TO LOVE) is still perceptible in another usage or implication of Romanticism when it is compared or contrasted with Realism. This usage is still somewhat current in modern English, e.g.

"S/he's a real Romantic." = dreamer, idealist, nonconformist, on a quest for undefined or unfamiliar goals

"Don't be so romantic. Be a realist."

Thus what is Romantic is often the long ago and far away rather than the here and now. (In science fiction, which is normally Romantic in plot and character, "the long ago" becomes "the future.")

For literary or cultural studies "Romantic" carries this dynamic range of meanings, but popular culture retains more specialized meanings for love, affection, the feelings . . .

"How romantic!" (e.g., loving couples escaping or transcending a heartless world, all consistent with the broader meaning.)

Overall, then, students of literature have to put up with some cognitive dissonance: "Romantic" and "romance" have two overlapping but distinct meanings.

Popular meanings: "Romantic" means love or sexiness; "romance" means a woman's love story.

Academic or historic meanings: Romanticism is a period or style of art involving many familiar and popular values and impulses. A romance is a type of story that may involve love but is not restricted to love; its defining characteristics are a journey or quest for self-transformation or fulfillment, as in a knight's quest for the Holy Grail, a heroine's attempt to rescue her baby, or an action hero's quest for revenge on the villain who killed a member of his family.

The concept of Romanticism has many potential contradictions but some consistencies, infinite variations, and many inspirations.

![]()

Goethe in the Roman Countryside

(1786)

by J.H.W. Tischbein

Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe

(1749-1832),

German poet, dramatist, novelist, scientist,

visual artist,

and primal figure of European Romanticism