|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

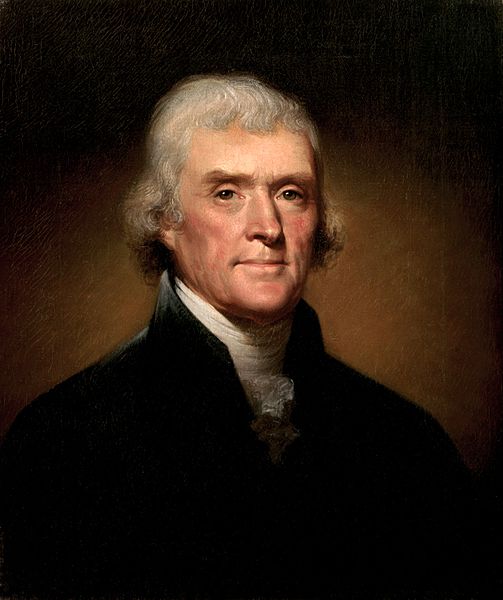

Thomas Jefferson

Writings on Religious Freedom |

|

Instructor's notes: Thomas Jefferson, third U.S. President & primary author of The Declaration of Independence, and James Madison, fourth U.S. President and "father of the U.S. Constitution," are the "Founding Fathers" who most directly made the United States a nation without an established state religion—a principle popularly identified as "freedom of religion" or "separation of church and state."

These Founding principles derived primarily from reaction against the devastating religious wars, bigoted persecutions, and horrifying tortures that characterized much of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in the 17th century, but also in response to the improvements in quality of life and standards of living brought about by the concurrent scientific revolution and improvements in secular technology, hygiene, nutrition, and education.

Jefferson and other Founders—including the more radical Thomas Paine—insisted they meant no disrespect to traditional religion, and their impact on religion may appear positively in several respects:

![]() If

Americans typically dislike government, separating religion from government

helps religion remain popular.

If

Americans typically dislike government, separating religion from government

helps religion remain popular.

![]() Whereas state-supported religions in European countries (e.g., the Anglican

Church in England) have declined precipitously in membership and attendance,

American church attendance remains high compared to other First-World or

developed nations.

Whereas state-supported religions in European countries (e.g., the Anglican

Church in England) have declined precipitously in membership and attendance,

American church attendance remains high compared to other First-World or

developed nations.

![]() The

rationale for American churches' comparative dynamism is that, by lacking direct

state support aside from lack of taxation, American churches participate in a

"market economy" in which the products they offer are packaged to meet the needs

of their supporters. Jefferson's Notes below support this idea in

paragraphs 9 & 10.

The

rationale for American churches' comparative dynamism is that, by lacking direct

state support aside from lack of taxation, American churches participate in a

"market economy" in which the products they offer are packaged to meet the needs

of their supporters. Jefferson's Notes below support this idea in

paragraphs 9 & 10.

![]()

"The Jefferson Bible," actually titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth was a copy of the Bible that Jefferson, using scissors and paste, edited to exclude all miracles attributed to Christ, including references to the Resurrection. What remains constitutes, in Jefferson's words, "the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man."

Index to online copy of "Jefforson Bible" at U. of Virginia library website

Wikipedia article on Jefferson Bible

![]()

Bill for Religious Freedom (Virginia); introduced by Jefferson in 1779, passed 1786

No man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burdened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.

[Jefferson's bill countered two earlier church-state practices: taxation in support of state-established ministries, and requirements that civil servants pass religious tests. As such, Jefferson's Bill for Religious Freedom becomes a model for the Constitution's First Amendment's non-establishment clause: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof . . . ."]

![]()

from Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1787)

"Religion"

The different religions received into that state?

[Jefferson's Notes are organized as replies to questions about

America or Vriginia from

a European correspondent]

Religion

[1] The first settlers in this country [Virginia] were emigrants from England, of the English [Anglican / Episcopal] church . . . . . Possessed, as they became, of the powers of making, administering, and executing the laws, they showed equal intolerance in this country with their Presbyterian brethren [Puritans], who had emigrated to the northern government [New England].

[2] The poor Quakers were flying from persecution in England. They cast their eyes on these new countries as asylums of civil and religious freedom; but they found them free only for the reigning sect [denomination]. Several acts of the Virginia assembly of 1659, 1662, and 1693, had made it penal [criminal] in parents to refuse to have their children baptized; had prohibited the unlawful assembling of Quakers . . . ; had inhibited all persons from suffering their meetings in or near their houses, entertaining them individually, or disposing of [handling] books which supported their tenets.

[3] If no capital execution took place here [i.e., Virginia*], as did in New-England, it was not owing to the moderation of the church . . . . The Anglicans retained full possession of the country about a century. Other opinions began then to creep in, and the great care of the government to support their own church, having begotten an equal degree of indolence in its clergy, two-thirds of the people had become dissenters* at the commencement of the present revolution. . . . [Jefferson implies that government support of religion works against religion’s interests by driving away believers and making ministers lazy; *"dissenters" = Christians who refuse to conform to state church, here Anglicanism or Episcopalianism] [*In contrast to Virginia, the Puritans banned Quakers and hanged a few who returned after banishment.]

[4] The error seems not sufficiently eradicated, that the operations of the mind, as well as the acts of the body, are subject to the coercion of the laws. But our rulers can have authority over such natural rights only as we have submitted to them. The rights of conscience we never submitted, we could not submit. We are answerable for them to our God.

[5] The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg. If it be said, his testimony in a court of justice cannot be relied on, reject it then, and be the stigma on him. Constraint may make him worse by making him a hypocrite, but it will never make him a truer man. It may fix him obstinately in his errors, but will not cure them. [cf. religious pluralism]

[6] Reason and free enquiry are the only effectual agents against error. Give a loose to them, they will support the true religion, by bringing every false one to their tribunal, to the test of their investigation. They are the natural enemies of error, and of error only.

[7] Had not the Roman government permitted free enquiry, Christianity could never have been introduced. Had not free enquiry been indulged, at the era of the reformation, the corruptions of Christianity could not have been purged away. If it be restrained now, the present corruptions will be protected, and new ones encouraged. . . . Galileo was sent to the inquisition for affirming that the earth was a sphere: the government had declared it to be as flat as a trencher [plate], and Galileo was obliged to abjure [retract] his error. This error however at length prevailed, the earth became a globe . . . .

[8] [T]he Newtonian principle of gravitation is now more firmly established, on the basis of reason, than it would be were the government to step in, and to make it an article of necessary faith. Reason and experiment have been indulged, and error has fled before them. It is error alone which needs the support of government. Truth can stand by itself. . . .

[9] Difference of opinion is advantageous in religion. The several sects perform the office of a Censor morum [censor of morals] over each other. Is uniformity [a single, unified church] attainable? Millions of innocent men, women, and children, since the introduction of Christianity, have been burnt, tortured, fined, imprisoned; yet we have not advanced one inch towards uniformity. What has been the effect of coercion? To make one half the world fools, and the other half hypocrites. To support roguery and error all over the earth. . . .

[10] Reason and persuasion are the only practicable instruments. To make way for these, free enquiry must be indulged; and how can we wish others to indulge it while we refuse it ourselves[?] But every state, says an inquisitor, has established some religion. No two, say I, have established the same. Is this a proof of the infallibility of establishments? Our sister states of Pennsylvania and New York, however, have long subsisted without any establishment [of a state religion] at all. The experiment was new and doubtful when they made it. It has answered beyond conception. They flourish infinitely. Religion is well supported; of various kinds, indeed, but all good enough; all sufficient to preserve peace and order: or if a sect arises, whose tenets would subvert morals, good sense has fair play, and reasons and laughs it out of doors, without suffering the state to be troubled with it.

[11] They [states not supporting religion] do not hang more malefactors than we do. They are not more disturbed with religious dissensions. On the contrary, their harmony is unparalleled, and can be ascribed to nothing but their unbounded tolerance, because there is no other circumstance in which they differ from every nation on earth. They have made the happy discovery, that the way to silence religious disputes, is to take no notice of them. [Contrarily, popular religions often glory in oppression, from the Christians in Rome to “the War on Christmas”]

[12] Let us too give this experiment fair play, and get rid, while we may, of those tyrannical laws. It is true, we are as yet secured against them by the spirit of the times. . . . But is the spirit of the people an infallible, a permanent reliance? Is it government? Is this the kind of protection we receive in return for the rights we give up?

[13] Besides, the spirit of the times may alter, will alter. Our rulers will become corrupt, our people careless. A single zealot [fanatic] may commence persecutor, and better men be his victims. It can never be too often repeated, that the time for fixing every essential right on a legal basis is while our rulers are honest, and ourselves united. From the conclusion of this war we shall be going down hill. It will not then be necessary to resort every moment to the people for support. They will be forgotten, therefore, and their rights disregarded. They [the people] will forget themselves, but [except] in the sole faculty of making money, and will never think of uniting to effect a due respect for their rights. The shackles, therefore, which shall not be knocked off at the conclusion of this war, will remain on us long, will be made heavier and heavier, till our rights shall revive or expire in a convulsion.

Jefferson, portrait by Rembrandt Peale, 1800