Classic literature or art

is above all works that survive through institutions like schools, religious

traditions, or learned societies. Classical literature

enjoys a long

shelf-life but

its popularity may be limited to literate, elite, or schooled culture. Compared

to popular literature, classic literature is under-exposed

except in schools.

"A classic is something everybody wants to have read, but no one wants to

read."—Mark Twain

Twain's line is funny for sympathizing with humanity's

weaknesses, but "wants to have read" admits the prestige or social capital of

classics.

In Literature's ongoing balancing act between

entertainment and education, classic literature tilts toward education or learning and

is less likely to

indulge cheap thrills or escapism.

"Education" may include

broadening the mind,

broadening the mind,

cultural literacy,

cultural literacy,

vocabulary-building,

vocabulary-building,

modeling,

modeling,

ethics,

ethics,

empathy,

empathy,

critical thinking,

critical thinking,

cultural or historical critiques

concerning social or personal justice,

cultural or historical critiques

concerning social or personal justice, mental-emotional exercise,

mental-emotional exercise,

attention-span extension

(deferred gratification), and discipline.

attention-span extension

(deferred gratification), and discipline.

Popular literature and culture are what most people want to read,

largely because they're easier and more immediately gratifying. They stick to proven formulas (as in "sequels" or

"knock-offs") to capitalize on previously-proven winners. They're

familiar and unchallenging, in contrast to the demands classic literature makes

on a reader.

A classic text,

instead of being highly predictable, self-consciously innovates, extends, reforms, or

even parodies previous styles and

contents from earlier texts in its tradition. Like evolution, classic literature continues what has come before but

also adapts to fresh experience and challenging knowledge. (Popular

literature also changes but follows rather than leads, supporting status quo.)

A simple formula for classic literature is "a book that

won't stay closed." A classic text keeps producing meaning for one generation

after another, in different contexts, for audiences with different mind-sets and

needs—even though the text still speaks with the same words!

Classics don't always stay classics, though.

Competition from new texts is always crowding out some older ones, and tastes

and needs change.

In sum, what counts as "classic literature" remains

fairly stable but also changes according to what's being written, what gets

taught, and who's sitting in the classrooms. (See representative literature

below.)

Popular literature or art

is the kind of literature that readers talk about excitedly and want to read as

though it is news or a change in lives of people they care about—for instance, a

new installment in a series like Twilight, Hunger Games, Tom

Clancy's novels featuring Jack Ryan, or any other detective, spy, or action

series with a glamorous, super-competent hero or team.

Instead of surviving indefinitely in schools and libraries, popular literature

lives and dies by the momentary marketplace when it appears in popular culture. Successful popular

literature sells well and becomes well-known to a wide audience, but compared to

classic literature or art it is often over-exposed, shorter-lived, and soon

forgotten or replaced with follow-ups, sequels, etc. (e.g., hit songs on the radio sound old a month or year

later).

Sentimental style, sensational events, and stereotypical formulas like sensitive vampires, exploding

helicopters, helpful dogs, and lost children are predictable, but they please wide audiences by

reinforcing familiar tastes and attitudes, confirming what everybody already

thinks and appealing to what is

already known.

(In contrast, classic literature usually takes you beyond your

comfort zone.)

Representative literature /

art

(sometimes called "multicultural," "diverse,"

"marginalized," or

"under-represented")

is

often

neglected or unknown except by special audiences, or written by

marginal or repressed races, classes, or genders.

Popularity or status of representative

literature may

change in relation to social needs.

Popularity or status of representative

literature may

change in relation to social needs.

Representative literature challenges conventional wisdom and styles from outside.

Representative literature challenges conventional wisdom and styles from outside.

Representative literature's style may

not fit perfectly with

dominant-culture styles, but it may challenge or refresh what's become old

or "official."

Representative literature's style may

not fit perfectly with

dominant-culture styles, but it may challenge or refresh what's become old

or "official."

Historic

events or references may be unfamiliar to dominant-culture

audiences.

Historic

events or references may be unfamiliar to dominant-culture

audiences.

However, genres and styles

of multicultural outsiders may vary expectations or norms to point of exclusion.

However, genres and styles

of multicultural outsiders may vary expectations or norms to point of exclusion.

Traditionally-schooled readers may wonder, "What do I do with that?" (The

outsider text may challenge ability to read with other texts in schools.)

Traditionally-schooled readers may wonder, "What do I do with that?" (The

outsider text may challenge ability to read with other texts in schools.)

Representative literature may enjoy some freshness or appeal by being previously

unknown or marginalized, eliciting Romantic

support for the underdog or outsider.

Representative literature may enjoy some freshness or appeal by being previously

unknown or marginalized, eliciting Romantic

support for the underdog or outsider.

|

|

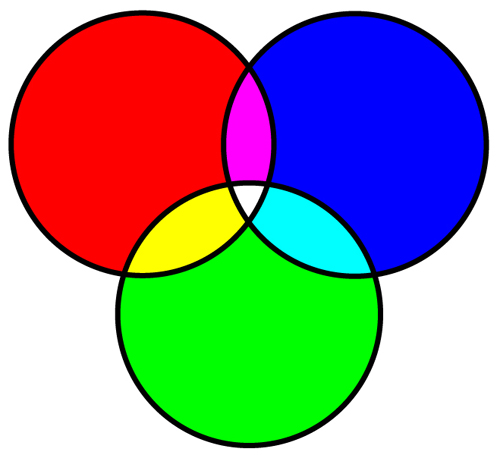

Classic

|

Popular

|

Representative

|

|

Sales / Audience

|

Usu. Low on

publication, but critical praise > libraries > anthologies > academy

|

Usu. high sales

on publication, but lack of critical praise limits “shelf life”

(exception: family favorites)

|

Local or

special audiences? “unofficial" (but “special collections”)

|

|

Style / appeal

|

Self-conscious,

learned, refined, controlled; intellectual, ahead of time

|

Colloquial; less self-conscious, "out of control," sentimental,

predictable

|

Non-academic,

Non-standard. “A voice is heard”; representation for under-represented.

|

Genres

|

Reformulated,

advanced, played with

|

Formulaic

with contemporary innovations

|

sometimes hard to

Categorize; e.g., autobiography / fiction

|

|

Attitude toward literary tradition

|

Reverent?

respectful, hierarchical. The tradition is known and acknowledged.

|

Irreverent or

oblivious; populist, democratic; writer may know and redevelop

previous models but doesn't assume reader has ever read anything else.

|

Ambivalent:

desire for acceptance yet acknowledgement of differences

|

|

Range of reference

|

Historical,

mythological, classical, "timeless"

|

Contemporary,

popular, passing scene; “life’s rich pageant” but often chaotic or

limited to current scene

|

Down to earth,

but relevance may be elusive to mainstream readers (Why telling me this?

What context? Culture confusion)

|

|

Gender / ethnic / class ID

|

"DWEMs": Dead

White European Males + a few women & people of color (Dickinson,

Douglass,

Wharton,

Cather, O'Connor, Ellison, Morrison); time, leisure required for

production / consumption

|

Women writers

well represented; audience largely female; other pressing concerns

(family?) require rapid production / consumption

|

Under-represented ethnic groups; sometimes language differences, +

reading habits may differ (continuation of oral traditions?)

|

Religion

|

Knowledgeable but “cool” or distanced; single

religious traditions become “relativized” in vast range of reference (e.

g., Emerson)

|

“Sentimental” (e. g., parent reclaims lost child /

sheep) but familiar, comforting, plus casting of evil and social wrongs

into gothic forms

|

Evangelical or “hot” religion often as basis of

emerging identity, claims for equality; tradition gains power as range

of reference diminishes

|

|

Other factors—esp. appeals to literary study

|

Classics often benefit from repeated readings;

“book that stays open” + classics refer to each other, so one gains

mastery over reading career

|

popular literature is easy to process;

“camp” pleasures vs. redemption of lifelong investment. Popular

literature typically doesn't benefit from repeated readings

|

Deepens apparently “new” tradition: "They were

saying that then?” (e.g. 19c feminism; equal rights for all)

May benefit from repeated readings as one learns to

read another culture.

|

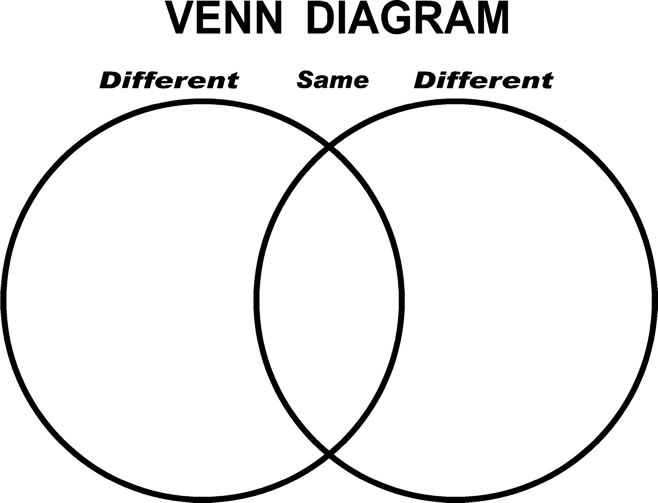

These categories are not

mutually exclusive

|

Authors both Classic & Popular

|

Authors both Classic & Representative

|

Shakespeare

John

Bunyan (The Pilgrim's Progress)

Daniel Defoe (Adventures

of Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders)

Charles Dickens (Great Expectations, A Christmas Carol)

Edgar Allan Poe

Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre

Susan B. Warner, The Wide, Wide World

Mark Twain

John Steinbeck (Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men)

|

Frederick Douglass

Langston Hughes

Toni Morrison

Sandra Cisneros

Chinua Achebe

Ngugi Wa Thiongo

Louise Erdrich |

Additional notes

Popular literature meets people where they are, confirms

their attitudes, values, or self-identifications. It "pushes their buttons."

Formulas

and genres are used more or less unconsciously or without embarrassment:

"If

this is an action movie, when does the helicopter explode?" (Or, "When does

the hero leap through a shattering glass window?")

"If

this is an action movie, when does the helicopter explode?" (Or, "When does

the hero leap through a shattering glass window?")

"If

this is a gothic thriller, when's the first scream in the night?" (Or, "When's the

first turn-around-and-gasp?")

"If

this is a gothic thriller, when's the first scream in the night?" (Or, "When's the

first turn-around-and-gasp?")

"If

this is a romantic comedy, when does the normative white heterosexual couple meet cute?"

"If

this is a romantic comedy, when does the normative white heterosexual couple meet cute?"

Popular

literature throws a lot of contemporary junk into a miscellaneous mix: every

page has something that excites or soothes or otherwise interfaces with familiar

needs and satisfactions.

Classic literature often involves

"deferred gratification," long attention spans, and unanswered

questions or unresolved problems. (Since classic literature doesn't

often offer a simple conclusion or wrap-up, the text remains alive in people's

minds and continues to challenge future generations.)

Plus classic literature strives for

"compositional integrity": parts aren't just thrown together but fit

carefully into larger patterns of meaning.

Representative literature:

Religious (or moral) content is sometimes foregrounded,

whereas for the dominant culture religion is often repressed, marginalized, or

carefully integrated into a secular mix.

Political & historical issues are introduced,

often highlighting past injustice and

victimization, which complicates "one story" of America's or the

world's people.

How is the mix of Classic, Popular, and

Representative literature shaking out nationally

in terms of what people read in schools?

Classic literature still dominates. Teachers teach what they learned

as students.

Possible changes afoot:

Literature > "Humanities,"

inter-disciplinary study, team-teaching with history, art, etc.

"Read whatever, but

read." > reading

list becomes what students are capable of reading or willing to read rather than

what they should read

Literature courses will probably hang on,

more or less.

Example of

Popular Literature: film review of Battleship (2012)

Aliens, Your Weapons Are Utterly Useless Against Our

Rogues

by Neil Genzlinger,

New York Times

17 May 2012

You would think that after

intercepting broadcasts of science-fiction movies for decades,

extraterrestrials would know that if they want to conquer us Earthlings

they need to take out our lovably rebellious rogues and our

unexpectedly heroic nerds.

Certainly

the makers of "Battleship," a cacophonous new special-effects

extravaganza inspired (sort of) by a game youngsters once

played with pencils and graph paper, have studied those old

movies. You can tell because they seem to have borrowed rather a lot

from them.

"Battleship,"

the latest

filmmaking project of the Hasbro toy company, has a plot as unambitious

as a macaroni dinner, familiar and easy to eat and not particularly

nutritious. It is likely to remind you variously of

"Independence Day," "Armageddon," "War of the Worlds" and

assorted other space-based yarns. Which of course means there’s

never much doubt about how it will end. . . .

link to outstanding student exam on classic,

popular, and representative

Stephen King as

popular or classic author?

![]()