|

Craig White's Literature Courses

Mimesis "Art imitates life [or nature, or reality]." |

This is not a sphere. Maybe it is. |

Mimesis (Oxford English Dictionary) 1b. Imitation; spec. the representation or imitation of the real world in (a work of) art, literature, etc.

Etymology: From Greek mimesis, from mimeisthai (to imitate). (Related words include mimic, mime, and mimosa.)

"Mimesis" is not familiar in everyday speech, and there's not an everyday word that means exactly the same thing (or all the things it means). The concept is so basic to human consciousness and action, and it reaches in so many different directions, that an unfamiliar word may be necessary.

Standard English synonyms for mimesis include "imitation," "representation," or, in some senses, "identification."

According to mimesis, art (or literature) imitates reality, nature, or life—an idea so ancient and widespread that, like "art's purpose is to entertain and educate," variations in wording and phrasing abound.

Aristotle in his Physics (350BCE) writes, he techne mimeitai ten physin, usually translated as ''Art imitates nature''—or reality—or life.

Popular metaphors or analogies for mimesis include art as a mirror, or a window, or, in one Shakespearean metaphor, "All the world's a stage."

In another Shakespearan metaphor, Hamlet 3.2 says that the "the purpose of [drama], whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold as 'twere the mirror up to nature." (3.2); i.e., when an audience watches a play or a movie, they are looking into a mirror—or out a window—that reflects or depicts their expectations of the way life is or should or shouldn't be.

An example of mimesis in everyday American speech is when a person likes a movie or song because s/he "identifies" with it. To identify here means recognizing resemblances between a work of art and oneself (or an idealized conception of oneself or one's world).

From an audience perspective, art's creation of another world like but not identical to the real world can be felt when a viewer feels absorbed in a film or drama, or a reader becomes absorbed or engrossed in a novel—as though the imaginary world were realer than the world in which the reader sits and breathes.

The idea of mimesis is so conventional and pervasive that it's difficult to know where it begins or ends. As with networks of symbols, our consciousness is built from a mimetic understanding of reality.

We can't think outside of symbols or mimesis.

For example, not only does art imitate life, but life imitates art (as, for instance, when we see a movie and walk out trying to act cool like our favorite star, or when we get married and expect to live high, fast, and free like in books or movies).

![]()

Mimesis may also distinguish types of writing such as creative writing or fiction versus critical writing or nonfiction.

Critical writing or nonfiction refers to a reality outside the text—for instance, a news story refers to an event that happened and describes it, or a literary essay describes and evaluates a work of literature. This kind of writing emphasizes the significance or meaning of a reality that is referred to rather than created.

Creative writing is more mimetic in that it creates a world in and of itself. Creative writing may refer to a larger world beyond the text, but only for the sake of reinforcing the meaning of the text itself.

Thus a reader may feel "drawn in" to a mimetic or creative art like a movie or a novel, which may feel realer or more compelling than the reality in which the reader actually exists. (For instance, the novel may take you to a desert island when you're actually sitting with a book in your room.)

In contrast, when reading a news article or a critical essay, a reader selects information and applies the information to the reality outside the text (even if the reality is another text). A reader is only occasionally "drawn in" to another world; instead the reader reads from a "critical distance" that helps analyze or synthesize the ideas of the nonfictional information in relation to previous ideas or knowledge. (See fiction and nonfiction.)

Either type of writing may do some of either—that is, the best nonfiction or critical writing makes sense of the world so much that the world may become realer in the text than it is outside; or fiction may provide information about the nature of the world beyond the text, as in historical fiction.

Critical and analytic writing pulls the world apart into themes, theses, ideas, positions, opinions, divisions, dialectics, parts of the world to be defended, developed, or attacked.

Creative writing, in imitating the world or its realities, puts the parts of a world back together again, so that all themes or ideas are exposed as overly simple and re-complicated, just as real life does to any and all ideas. More simply, a creative text creates a world unto itself.

![]()

from Aristotle. Poetics. ca. 340 BCE.

I. Epic poetry and tragedy, comedy also . . . are all in their general conception modes of imitation [or mimesis, or representation]. They differ, however, from one another in three respects—the medium, the objects, the manner or mode of imitation [mimesis], being in each case distinct. . . .

IV. Poetry in general seems to have sprung from two causes, each of them lying deep in our nature.

First, the instinct of imitation [mimesis] is implanted in [humanity] from childhood, one difference between [the human] and other animals being that people are the most imitative of living creatures, and through imitation we learn our earliest lessons;

and [second,] no less universal is the pleasure felt in things imitated . . . . The cause of this again is, that to learn gives the liveliest pleasure, not only to philosophers but to [humans] in general; whose capacity, however, of learning is more limited. Thus the reason why men enjoy seeing a likeness is, that in contemplating it they find themselves learning or inferring, and saying perhaps, "Ah, that is he." For if you happen not to have seen the original, the pleasure will be due not to the imitation as such, but to the execution, the coloring, or some such other cause.

Imitation, then is one instinct of our nature. . . .

![]()

from Plato,

The Republic. c. 373 BCE. Benjamin Jowett, translator.

The Dialogues of Plato, 4th ed.

(Oxford, Eng.: Clarendon, 1953); reprinted in Hazard Adams, ed.

Critical Theory since Plato (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,

1971): 19-40.

God [or reality] is always to

be represented as he truly is, whatever be the

sort of poetry, epic, lyric, or tragic, in which the representation

is given. . . .

[N]arration may be either

simple narration, or imitation, or a

union of the two. . . .

[S]ome poetry and mythology

are wholly imitative ( . . . I mean

tragedy and comedy); there is likewise the opposite style, in which the poet

is the only speaker--of this the dithyramb [or

lyric] affords the best example; and

the combination of both is found in epic

[or, now, the novel] . . . .

Usage

"Mimesis was seldom the only purpose of art, but always a central one: to

make pictures look 'real.' After photography, however, all this changed." —

Richard Nilsen; Perceptions Always in Flux; The Arizona Republic (Phoenix); May

30, 2004.

"Civilizations, he wrote, are invented by a creative minority that appears

from time to time and creates art, ideas, forms and substance. It forges an

intellectual universe, which the non-creative majority enters by mimesis,

adopting, following and embellishing, which may lead to high culture." — T.R.

Fehrenbach; Creativity Builds Great Civilizations, Followed By ... Not Much; San

Antonio Express-News (Texas); Jun 27, 2004.

![]()

"Virtual reality" is, like art, a human creation that is not nature or reality or even biological life but rather a representation in which we imaginatively share (with physical borders increasingly blurry).

Language itself is virtual reality. These words or signs are not what they describe but only cultural conventions that would be meaningless to anyone without the necessary language training; compare computer languages.

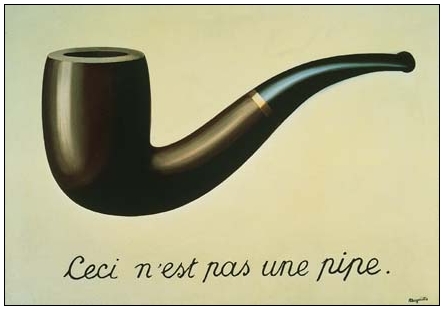

A famous example that reinforces the difference between art and reality is the surrealist painter Rene Magritte's La Trahison des Images or The Treachery of Images, a painting of a smoking pipe whose inscription reads, "This is not a pipe."

Then again, the pipe isn't nature either but a human artifact. Such multi-layered complications are a reason why mimesis is known but only briefly discussed.

![]()

Mimesis as a selection of reality: No work of art fully reproduces the real world. Art invariably selects which parts of the world to depict, and which parts are chosen determines how they are depicted.

No story depicting a character's life tells a reader or viewer everything that happens. Instead art depicts what matters, what is symbolic in some sense.

Example: Art normally doesn't show a person putting on and tying their shoes, even though in real life everyone has to do it. Art might show it if something about the character's shoes somehow matters and thus becomes symbolic or meaningful.

On a larger scale, a difference between ideal / romantic art or literature vs. realistic art or literature is what or how much reality they represent.

Romanticism or idealization streamlines reality by foregrounding bold figures against abstract backgrounds.

Realistic art makes foreground figures smaller and clutters the background with lots of details.

![]()

Mimesis as a criterion of literary quality:

Popular literature tends to simplify reality drastically through good-evil characterizations (heroes and villains, helpers and victims), familiar symbolic settings (fairy-tale kingdoms, gothic spaces), and contrived plotting (e.g. conspiracy theories, first love, mean teachers) that indulge popular preconceptions.

Serious or classic literature works to reflect or embody the complexity of natural and social reality, which is partly what makes classical literature harder to read.)

![]() Characterization and character-motivation are more mixed, so good and bad become

harder to isolate from each other (as in real life).

Characterization and character-motivation are more mixed, so good and bad become

harder to isolate from each other (as in real life).

![]() Settings

may be illusory or have additional meanings beyond first impressions.

Settings

may be illusory or have additional meanings beyond first impressions.

![]() Plots or

narratives may be more open-ended, less easily defined or resolved; lack

of resolution can prompt further thought, discussion, etc.

Plots or

narratives may be more open-ended, less easily defined or resolved; lack

of resolution can prompt further thought, discussion, etc.

![]()

web definitions:

the imitative

representation of nature and human behavior in art and literature; the

representation of another person's words in a speech

wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn

The

representation of aspects of the real world, especially human actions, in

literature and art; mimicry . . .

en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mimesis

mimetic - characterized by or of the nature of or using mimesis; "a mimetic dance"; "the mimetic presentation of images"

mimetic -

exhibiting mimicry; "mimetic coloring of a butterfly"; "the mimetic tendency of

infancy"- R.W.Hamilton

wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn