|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

selections from Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682)

|

|

[from title page]

The sovereignty and goodness of GOD, being

a narrative of the captivity and restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson

The sovereignty and goodness of GOD, together with the faithfulness of his promises displayed, being a narrative of the captivity and restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, commended by her, to all that desires to know the Lord's doings to, and dealings with her. Especially to her dear children and relations. The second Addition [sic] Corrected and amended. Written by her own hand for her private use, and now made public at the earnest desire of some friends, and for the benefit of the afflicted. Deut. 32.39. See now that I, even I am he, and there is no god with me, I kill and I make alive, I wound and I heal, neither is there any can deliver out of my hand.

![]()

Significance to course:

-

First “captivity narrative,” a type of story recurring throughout American literature

-

Anticipates popular fiction: action, blood, suffering, separation and redemption—a page-turner

-

Anticipates gothic color code by depicting Indian “other” as dark, hellish, cunning, unpredictable.

-

American Indian then plays similar role as terrorists play now.

-

Opportunity for a woman’s writing and experience in a male-dominant society and literature

-

Interpretation of American experience as Christian allegory, but glimpses of American Indians as experiencing another kind of story.

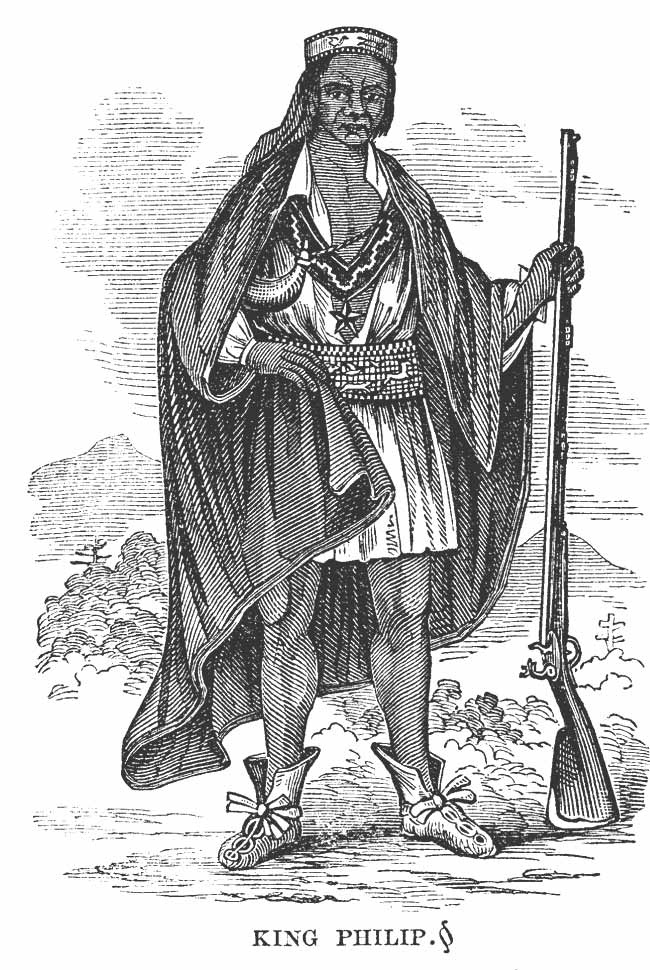

Minimal historical context: the events take place during “King Philip’s War” (1675-6), the last major Indian effort to overcome English settlement of New England.

Style note: The text dramatically begins in medias res—“in the middle of things.”

|

|

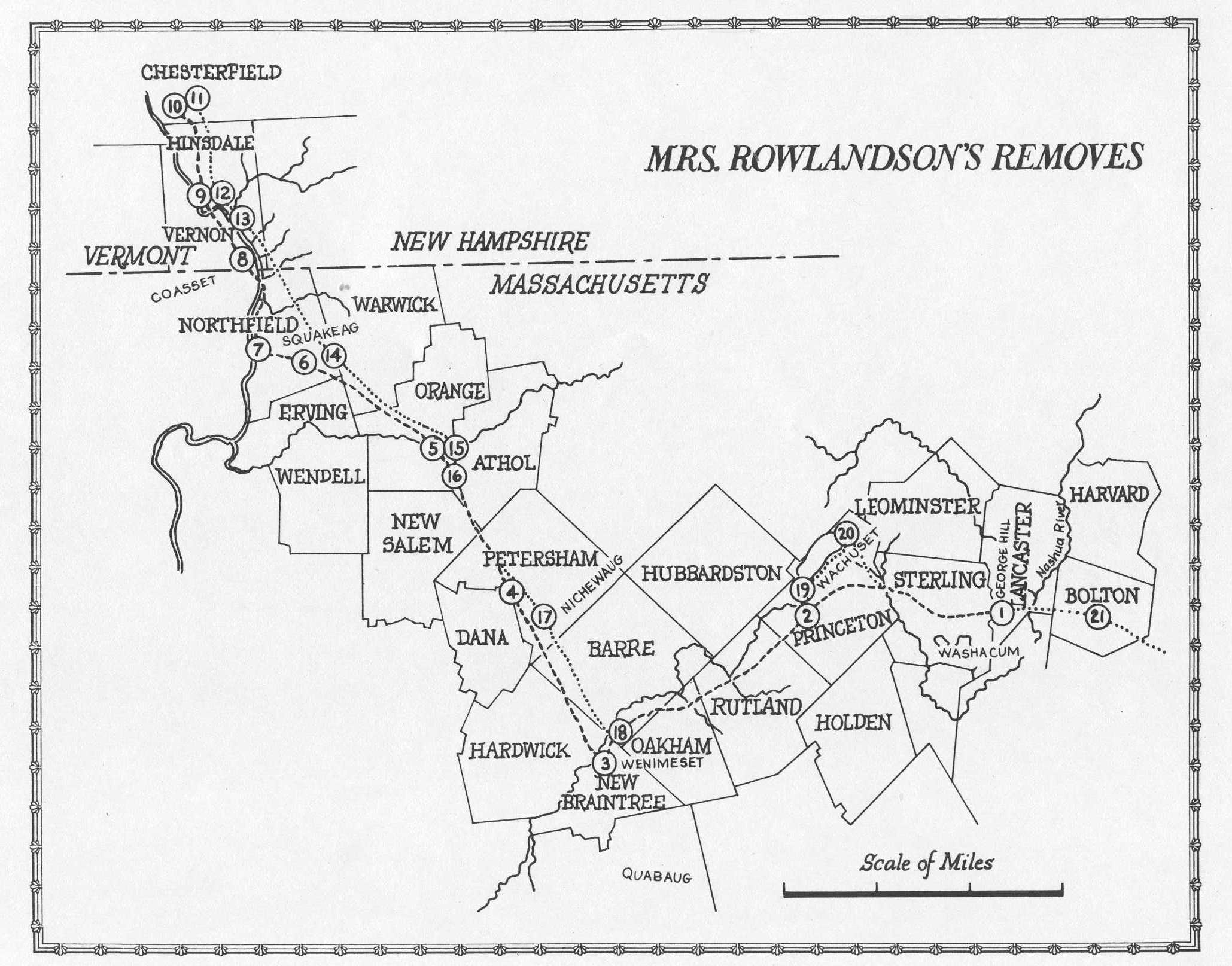

Initial setting: the frontier town of Lancaster, Massachusetts in 1675. Map at right: green star is Lancaster > Chapters of Rowlandson's narratives

are called "Removes" [i.e. relocations]. |

|

![]()

[Opening]

[0.1] On the tenth of February 1675, came the Indians with great numbers upon Lancaster [small Massachusetts frontier town]: their first coming was about sunrising; hearing the noise of some guns, we looked out; several houses were burning, and the smoke ascending to heaven.

[0.1a] There were five persons taken in one house; the father, and the mother and a sucking child, they knocked on the head; the other two they took and carried away alive. There were two others, who being out of their garrison upon some occasion were set upon; one was knocked on the head, the other escaped; another there was who running along was shot and wounded, and fell down; he begged of them [the Indians] his life, promising them money (as they told me) but they would not hearken to him but knocked him in head, and stripped him naked, and split open his bowels [belly]. Another, seeing many of the Indians about his barn, ventured and went out, but was quickly shot down. There were three others belonging to the same garrison [fortified house] who were killed; the Indians getting up upon the roof of the barn, had advantage to shoot down upon them over their fortification. Thus these murderous wretches went on, burning, and destroying before them.

[0.2] At length they came and beset our own house, and quickly it was the dolefulest [saddest] day that ever mine eyes saw. The house stood upon the edge of a hill; some of the Indians got behind the hill, others into the barn, and others behind anything that could shelter them; from all which places they shot against the house, so that the bullets seemed to fly like hail; and quickly they wounded one man among us, then another, and then a third. About two hours (according to my observation, in that amazing [confusing] time) they had been about the house before they prevailed to fire it (which they did with flax and hemp [plant fibers], which they brought out of the barn, and there being no defense about the house, only two flankers [fortifications?] at two opposite corners and one of them not finished); they fired it [torched the house] once and one [an inhabitant] ventured out and quenched it, but they quickly fired it again, and that took [caught fire].

[0.2a] Now is the dreadful hour come [as in Day of Judgment?], that I have often heard of (in time of war, as it was the case of others), but now mine eyes see it. Some in our house were fighting for their lives, others wallowing in their blood, the house on fire over our heads, and the bloody heathen ready to knock us on the head, if we stirred out. Now might we hear mothers and children crying out for themselves, and one another, "Lord, what shall we do?"

[0.2b] Then I took my children (and one of my sisters', hers) to go forth and leave the house: but as soon as we came to the door and appeared, the Indians shot so thick that the bullets rattled against the house, as if one had taken an handful of stones and threw them, so that we were fain to give back. We had six stout dogs belonging to our garrison, but none of them would stir, though another time, if any Indian had come to the door, they were ready to fly upon him and tear him down. The Lord hereby would make us the more acknowledge His hand, and to see that our help is always in Him.

[0.2c] But out we must go, the fire increasing, and coming along behind us, roaring, and the Indians gaping before us with their guns, spears, and hatchets to devour [destroy] us. No sooner were we out of the house, but my brother-in-law (being before wounded, in defending the house, in or near the throat) fell down dead, whereat the Indians scornfully shouted, and hallowed [hollered], and were presently upon him, stripping off his clothes, the bullets flying thick, one went through my side, and the same (as would seem) through the bowels [belly] and hand of my dear child [her youngest daughter being carried] in my arms. One of my elder sisters' children, named William, had then his leg broken, which the Indians perceiving, they knocked him on [his] head.

[0.2d] Thus were we butchered by those merciless heathen, standing amazed [stunned], with the blood running down to our heels. My eldest sister being yet in the house, and seeing those woeful sights, the infidels hauling mothers one way, and children another, and some wallowing in their blood: and her elder son telling her that her son William was dead, and myself was wounded, she said, "And Lord, let me die with them," which was no sooner said, but she was struck with a bullet, and fell down dead over the threshold. I hope she is reaping the fruit of her good labors, being faithful to the service of God in her place. In her younger years she lay under much trouble upon spiritual accounts, till it pleased God to make that precious scripture take hold of her heart, "And he said unto me, my Grace is sufficient for thee" (2 Corinthians 12.9). More than twenty years after, I have heard her tell how sweet and comfortable that place [scripture passage] was to her.

[0.2e] But to return: the Indians laid hold of us, pulling me one way, and the children another, and said, "Come go along with us"; I told them they would kill me: they answered, if I were willing to go along with them, they would not hurt me.

[0.3] Oh the doleful sight that now was to behold at this house! "Come, behold the works of the Lord, what desolations he has made in the earth." [<Psalm 46.8] Of thirty-seven persons who were in this one house, none escaped either present death, or a bitter captivity, save only one, who might say as he, "And I only am escaped alone to tell the News" (Job 1.15). There were twelve killed, some shot, some stabbed with their spears, some knocked down with their hatchets. When we are in prosperity, Oh the little that we think of such dreadful sights, and to see our dear friends, and relations lie bleeding out their heart-blood upon the ground. There was one who was chopped into the head with a hatchet, and stripped naked, and yet was crawling up and down.

[0.3a] It is a solemn sight to see so many Christians lying in their blood, some here, and some there, like a company of sheep torn by wolves, all of them stripped naked by a company of hell-hounds, roaring, singing, ranting, and insulting [cf. descriptions of terrorists + hellish imagery like gothic], as if they would have torn our very hearts out; yet the Lord by His almighty power preserved a number of us from death, for there were twenty-four of us taken alive and carried captive.

[0.4] I had often before this said that if the Indians should come, I should choose rather to be killed by them than taken alive, but when it came to the trial my mind changed; their glittering weapons so daunted my spirit, that I chose rather to go along with those (as I may say) ravenous beasts, than that moment to end my days; and that I may the better declare what happened to me during that grievous captivity, I shall particularly speak of the several removes we had up and down the wilderness.

[Instructor’s notes on opening:

-

Family danger comparable to romance narrative

-

Compare Indians then to “Terrorists” now

-

0.2e, 0.4: Psychological journey: as events transpire, Rowlandson changes her mind: correspondence]

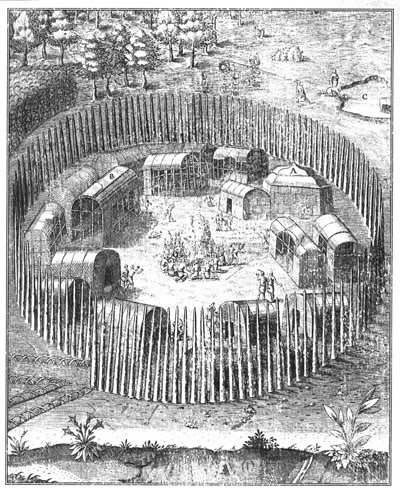

![]()

|

from The First Remove [Rowlandson organizes narrative not by chapters but by “removes” = relocations of her journey] |

tree marks site of Rowlandson home |

[1.1] Now away we must go with those barbarous creatures, with our bodies wounded and bleeding, and our hearts no less than our bodies. About a mile we went that night, up upon a hill within sight of the town [her hometown Lancaster], where they intended to lodge. There was hard by [nearby] a vacant house (deserted by the English before, for fear of the Indians). I asked them whether I might not lodge in the house that night, to which they answered, "What, will you love English men still?"

[1.1a] This was the dolefulest [most dreadful] night that ever my eyes saw. Oh the roaring, and singing and dancing, and yelling of those black creatures in the night, which made the place a lively resemblance of hell. [Indians are fitted to the Christian worldview incl. darkness > gothic]

[1.1b] And as miserable was the waste that was there made of horses, cattle, sheep, swine, calves, lambs, roasting pigs, and fowl (which they had plundered in the town), some roasting, some lying and burning, and some boiling to feed our merciless enemies; who were joyful enough, though we were disconsolate.

[1.1c] To add to the dolefulness of the former day, and the dismalness of the present night, my thoughts ran upon my losses and sad bereaved [grieving] condition. All was gone, my husband gone (at least separated from me, he being in the Bay [Massachusetts Bay, spec. Boston, Puritan capital]; and to add to my grief, the Indians told me they would kill him as he came homeward), my children gone, my relations and friends gone, our house and home and all our comforts—within door and without—all was gone (except my life), and I knew not but the next moment that might go too.

[1.1d] There remained nothing to me but one poor wounded babe, and it seemed at present worse than death that it was in such a pitiful condition, bespeaking compassion, and I had no refreshing for it, nor suitable things to revive it.

[1.1e] Little do many think what is the savageness and brutishness of this barbarous enemy, Ay, even those that seem to profess more than others among them, when the English have fallen into their hands. [In this last sentence, “profess” means expressing Christian sentiments, the first of several mistrustful references Rowlandson makes to “Praying Indians”—see next paragraph]

[1.2] Those seven [English settlers] that were killed at Lancaster the summer before upon a Sabbath day, and the one that was afterward killed upon a weekday, were slain and mangled in a barbarous manner, by one-eyed John [an Indian leader], and Marlborough's Praying Indians, which Capt. Mosely [an English supporter of the Praying Indians] brought to Boston, as the Indians told me.

[Instructor's note: "Praying Indians" were Indians converted to Christianity, most of them living in several villages organized by missionary John Eliot, "the Apostle to the Indians." Praying Indians often served as intermediaries between the Puritans and the unconverted Indians but were mistrusted by either side, as Rowlandson's attitude reveals.]

![]()

|

|

|

[2.1] But now, the next morning, I must turn my back upon the town, and travel with them [Indians] into the vast and desolate wilderness, I knew not whither. It is not my tongue, or pen, can express the sorrows of my heart, and bitterness of my spirit that I had at this departure: but God was with me in a wonderful manner, carrying me along, and bearing up my spirit, that it did not quite fail.

[2.1a] One of the Indians carried my poor wounded babe upon a horse; it [daughter] went moaning all along, "I shall die, I shall die." I went on foot after it [her], with sorrow that cannot be expressed. At length I took it off the horse, and carried it in my arms till my strength failed, and I fell down with it.

[2.1b] Then they set me upon a horse with my wounded child in my lap, and there being no furniture [saddle, tack] upon the horse's back, as we were going down a steep hill we both fell over the horse's head, at which they [the Indians], like inhumane creatures, laughed, and rejoiced to see it, though I thought we should there have ended our days, as overcome with so many difficulties.* But the Lord renewed my strength still, and carried me along, that I might see more of His power; yea, so much that I could never have thought of, had I not experienced it. [*Compare Indians’ insensitivity here to Rowlandson’s at 13.3]

[2.2] After this it quickly began to snow, and when night came on, they stopped, and now down I must sit in the snow, by a little fire, and a few boughs behind me, with my sick child in my lap; and calling much for water, being now (through the wound) fallen into a violent fever. My own wound* also growing so stiff that I could scarce sit down or rise up; yet so it must be, that I must sit all this cold winter night upon the cold snowy ground, with my sick child in my arms, looking that every hour would be the last of its life; and having no Christian friend near me, either to comfort or help me. Oh, I may see the wonderful power of God, that my Spirit did not utterly sink under my affliction: still the Lord upheld me with His gracious and merciful spirit, and we were both alive to see the light of the next morning. [*"wound" . . . in her side; see 0.2c above]

![]()

|

from The Third Remove |

|

[3.1] The morning being come, they [the Indians] prepared to go on their way. One of the Indians got up upon a horse, and they set me up behind him, with my poor sick babe in my lap. A very wearisome and tedious day I had of it; what with my own wound, and my child's being so exceeding sick, and in a lamentable condition with her wound. It may be easily judged what a poor feeble condition we were in, there being not the least crumb of refreshing [food] that came within either of our mouths from Wednesday night to Saturday night, except only a little cold water.

[3.1a] This day in the afternoon . . . , we came to the place where they intended, viz. an Indian town, called Wenimesset . . . . When we were come, Oh the number of pagans (now merciless enemies) that there came about me . . . .

[3.1b] The next day was the Sabbath. I then remembered how careless I had been of God's holy time; how many Sabbaths I had lost and misspent, and how evilly I had walked in God's sight; which lay so close unto my spirit, that it was easy for me to see how righteous it was with God to cut off the thread of my life and cast me out of His presence forever. Yet the Lord still showed mercy to me, and upheld me; and as He wounded me with one hand, so he healed me with the other. . . . [note internal exploration of psychology as soul-searching]

[3.1c] I sat much alone with a poor wounded child in my lap, which moaned night and day, having nothing to revive the body, or cheer the spirits of her, but instead of that, sometimes one Indian would come and tell me one hour that "your master* will knock your child in the head" . . . . [*"your master": later identified in 3.2b as the Indian leader Quinnapin)]

[3.2] Thus nine days I sat upon my knees, with my babe in my lap, till my flesh was raw again; my child being even ready to depart this sorrowful world, they bade me carry it out to another wigwam (I suppose because they would not be troubled with such spectacles) whither I went with a very heavy heart, and down I sat with the picture of death in my lap. About two hours in the night, my sweet babe like a lamb departed this life on Feb. 18, 1675. It being about six years, and five months old. . . . .

[3.2a] I cannot but take notice how at another time I could not bear to be in the room where any dead person was, but now the case is changed; I must and could lie down by my dead babe, side by side all the night after. I have thought since of the wonderful goodness of God to me in preserving me in the use of my reason and senses in that distressed time, that I did not use wicked and violent means to end my own miserable life. [another example—cf. 0.2e, 0.4—of the psychological changes accompanying Rowlandson's journey]

[3.2b] In the morning, when they understood that my child was dead they [Indians] sent for me home to my master's wigwam (by my master . . . must be understood Quinnapin, who was a Sagamore [chieftain], and married *King Philip's wife's sister . . . ). I went to take up my dead child in my arms to carry it with me, but they bid me let it alone; there was no resisting, but go I must and leave it. [Compare the Indians' insensitivity to the loss of Rowlandson's child here to her own insensitivity to the death of an Indian child below, 13.3] When I had been at my master's wigwam, I took the first opportunity I could get to go look after my dead child. When I came I asked them what they had done with it; then they told me it was upon the hill. Then they went and showed me where it was, where I saw the ground was newly digged, and there they told me they had buried it. There I left that child in the wilderness, and must commit it, and myself also in this wilderness condition, to Him who is above all. [*"King Philip": Wampanoag sagamore / chief who led the Indian insurrection known as King Philip's War]

[3.2c] God having taken away this dear child, I went to see my daughter Mary, who was at this same Indian town, at a wigwam not very far off, though we had little liberty or opportunity to see one another. She was about ten years old, and taken from the door at first by a Praying Ind[ian] and afterward sold for a gun. When I came in sight, she would fall aweeping; at which they were provoked, and would not let me come near her, but bade me be gone; which was a heart-cutting word to me. I had one child dead, another in the wilderness, I knew not where [<her son], the third they would not let me come near to . . .

[3.2d] I could not sit still in this condition, but kept walking from one place to another. And as I was going along, my heart was even overwhelmed with the thoughts of my condition, and that I should have children, and a nation which I knew not, ruled over them.

[3.2e] Whereupon I earnestly entreated the Lord, that He would consider my low estate, and show me a token for good, and if it were His blessed will, some sign and hope of some relief. And indeed quickly the Lord answered, in some measure, my poor prayers; for as I was going up and down mourning and lamenting my condition, my son came to me, and asked me how I did. I had not seen him before, since the destruction of the town, and I knew not where he was, till I was informed by himself, that he was amongst a smaller parcel of Indians, whose place was about six miles off. With tears in his eyes, he asked me whether his sister Sarah was dead; and told me he had seen his sister Mary; and prayed me, that I would not be troubled in reference to himself.

[3.2f] The occasion of his coming to see me at this time, was this: there was, as I said, about six miles from us, a small plantation of Indians, where it seems he had been during his captivity; and at this time, there were some forces of the Ind[ians] gathered out of our company, and some also from them (among whom was my son's master) to go to assault and burn Medfield [another English frontier town]. In this time of the absence of his master, his dame [wife] brought him [her son] to see me. I took this to be some gracious answer to my earnest and unfeigned desire [her prayer at 3.2e for “a token of good” and “hope of some relief”].

[3.2g] The next day, viz. to this, the Indians returned from Medfield, all the company . . . came through the [Indian] town that now we were at. But before they came to us, Oh! the outrageous roaring and hooping [whooping] that there was. They began their din [noise] about a mile before they came to us. By their noise and hooping they signified how many they had destroyed (which was at that time twenty-three). Those that were with us at home were gathered together as soon as they heard the hooping, and every time that the other went over their number, these at home [the Indians who stayed behind] gave a shout, that the very earth rung again. And thus they continued till those that had been upon the expedition were come up to the Sagamore's wigwam; and then, Oh, the hideous insulting and triumphing that there was over some Englishmen's scalps that they had taken (as their manner is) and brought with them.

[3.2h] I cannot but take notice of the wonderful mercy of God to me in those afflictions, in sending me a Bible. One of the Indians that came from Medfield fight, had brought some plunder, came to me, and asked me, if I would have a Bible, he had got one in his basket. I was glad of it, and asked him, whether he thought the Indians would let me read? He answered, yes.

[3.2i] So I took the Bible, and in that melancholy time, it came into my mind to read first the 28th chapter of Deuteronomy, which I did, and when I had read it, my dark heart wrought on this manner: that there was no mercy for me, that the blessings were gone, and the curses come in their room, and that I had lost my opportunity. But the Lord helped me still to go on reading till I came to Chap. 30, the seven first verses, where I found, there was mercy promised again . . . .

[3.3] Now the Ind[ians] began to talk of removing from this place, some one way, and some another. There were now besides myself nine English captives in this place (all of them children, except one woman). I got an opportunity to go and take my leave of them [the other captives]. They being to go one way, and I another, I asked them whether they were earnest with God for deliverance. They told me they did as they were able, and it was some comfort to me, that the Lord stirred up children to look to Him.

[3.3a] The woman, viz. goodwife Joslin, told me she should never see me again . . . . I had my Bible with me, I pulled it out, and asked her whether she would read. We opened the Bible and lighted on Psalm 27, in which Psalm we especially took notice of that, ver. ult. [final verse], "Wait on the Lord, Be of good courage, and he shall strengthen thine Heart, wait I say on the Lord."

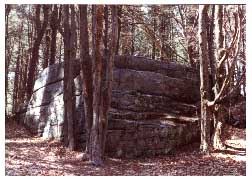

![]()

from The Fourth Remove |

Mount Grace, where Rowlandson's daughter was buried |

[4.1] And now I must part with that little company [of other English captives] I had. Here I parted from my daughter Mary (whom I never saw again till I saw her in Dorchester, returned from captivity*), and from four little cousins and neighbors, some of which I never saw afterward: the Lord only knows the end of them. . . . [*giving away ending reminds this text isn’t fiction; outcome is known]

[4.1a] But to return to my own journey, we traveled about half a day or little more, and came to a desolate place in the wilderness, where there were no wigwams or inhabitants before; we came about the middle of the afternoon to this place, cold and wet, and snowy, and hungry, and weary, and no refreshing for man but the cold ground to sit on, and our poor Indian cheer [hospitality].

[4.2] Heart-aching thoughts here I had about my poor children, who were scattered up and down among the wild beasts of the forest. My head was light and dizzy (either through hunger or hard lodging, or trouble or all together), my knees feeble, my body raw by sitting double night and day, that I cannot express to man the affliction that lay upon my spirit, but the Lord helped me at that time to express it to Himself. I opened my Bible to read, and the Lord brought that precious Scripture to me. "Thus saith the Lord, refrain thy voice from weeping, and thine eyes from tears, for thy work shall be rewarded, and they shall come again from the land of the enemy" (Jeremiah 31.16). This was a sweet cordial [refreshment] to me when I was ready to faint; many and many a time have I sat down and wept sweetly over this Scripture. At this place we continued about four days.

![]()

from The Fifth Remove |

|

[5.1] The occasion [cause] (as I thought) of their moving at this time was the English army, it being near and following them. For they [Indians] went as if they had gone for their lives, for some considerable way, and then they made a stop, and chose some of their stoutest men, and sent them back to hold the English army in play whilst the rest escaped. And then, like Jehu [2 Kings 9.24], they marched on furiously, with their old and with their young: some carried their old decrepit mothers, some carried one, and some another. Four of them carried a great Indian upon a bier [stretcher]; but going through a thick wood with him, they were hindered, and could make no haste, whereupon they took him upon their backs, and carried him, one at a time, till they came to Banquaug river. [Completing the earlier analogy between Indian warriors and “terrorists,” the Indian people here appear as “refugees”]

[5.1a] Upon a Friday, a little after noon, we came to this river. When all the company was come up, and were gathered together, I thought to count the number of them, but they were so many, and being somewhat in motion, it was beyond my skill.

[5.1b] In this travel, because of my wound, I was somewhat favored in [relieved of] my load; I carried only my knitting work* and two quarts of parched meal [cornmeal?]. Being very faint I asked my mistress [Quinnapin’s wife] to give me one spoonful of the meal, but she would not give me a taste. [*first mention of her increasing economic role making and trading clothes; cf. Cabeza de Vaca]

[5.1c] They quickly fell to [began] cutting dry trees, to make rafts to carry them over the river: and soon my turn came to go over. By the advantage of some brush which they had laid upon the raft to sit upon, I did not wet my foot (which many of themselves at the other end were mid-leg deep) which cannot but be acknowledged as a favor of God to my weakened body, it being a very cold time. [<Realistic detail; contrast Romantic fiction, in which depiction of adventures ignores such everyday details of survival] . . .

[5.1d] A certain number of us got over the river that night, but it was the night after the Sabbath before all the company was got over. On the Saturday they boiled an old horse's leg which they had got, and so we drank of the broth, as soon as they thought it was ready, and when it was almost all gone, they filled it up again.

[5.2] The first week of my being among them I hardly ate any thing; the second week I found my stomach grow very faint for want of something; and yet it was very hard to get down their filthy trash [repulsive food]; but the third week, though I could think how formerly my stomach would turn against this or that, and I could starve and die before I could eat such things, yet they were sweet and savory to my taste. [again Rowlandson changes her preconceptions in order to adapt to changing conditions]

[5.2a] I was at this time knitting a pair of white cotton stockings for my mistress [Quinnapin’s wife]; and had not yet wrought [worked, labored] upon a Sabbath day. When the Sabbath came they bade me go to work. I told them it was the Sabbath day, and desired them to let me rest, and told them I would do as much more tomorrow; to which they answered me they would break my face. [Besides a different religion, the Indians have no conception of 7-day weeks, which is not a natural division but a cultural inheritance from Genesis]

[5.2b] And here I cannot but take notice of the strange providence of God in preserving the heathen.* They were many hundreds, old and young, some sick, and some lame; many had papooses at their backs. The greatest number at this time with us were squaws, and they traveled with all they had, bag and baggage [<refugee scene], and yet they got over this river aforesaid; and on Monday they set their wigwams on fire, and away they went. [*Implicit question: if the Indians are enemies of God’s people, why doesn’t God simply arrange their swift extermination?]

[5.2c] On that very day came the English army after them to this river, and saw the smoke of their wigwams, and yet this river put a stop to them. God did not give them [the English army] courage or activity to go over after us* [Indians and captives]. We were not ready for [hadn’t earned] so great a mercy [favor from God] as victory and deliverance. If we had been[,] God would have found out a way for the English to have passed this river, as well as for the Indians [in the same manner as the Indians had] with their squaws and children, and all their luggage. "Oh that my people had hearkened to me, and Israel had walked in my ways, I should soon have subdued their enemies, and turned my hand against their adversaries" (Psalm 81.13-14).**

[*First time Rowlandson refers to Indian group as “us” instead of “them” or “they.”]

[**Rowlandson struggles not to criticize the English army for not being able to cross the river as the Indians had, though the Indians were traveling under less favorable conditions; the Psalm she cites also appears critical—but since it’s Scripture, she can offer it with impunity.]

![]()

from The Sixth Remove |

wetlands near Lancaster |

[6.1] On Monday (as I said) they set their wigwams on fire and went away. It was a cold morning, and before us there was a great brook [creek, stream] with ice on it; some waded through it, up to the knees and higher, but others went till they came to a beaver dam, and I amongst them, where through the good providence of God, I did not wet my foot.

[6.1a] I went along that day mourning and lamenting, leaving farther my own country, and traveling into a vast and howling wilderness*, and I understood something of **Lot's wife's temptation, when she looked back.

["a vast and howling wilderness": widely quoted phrase illustrating how seventeenth-century American settlers, unlike later Romantic writers, did not “love nature” but saw it as a threat]

[**"Lot's wife" in Genesis 19 was commanded by angels not to look back at Sodom, the town she was fleeing, but did so and was turned into a pillar of salt; strikingly affecting identification with Scripture] . . .

![]()

|

from The Seventh Remove |

|

[7.1] After a restless and hungry night there, we had a wearisome time of it the next day. The swamp by which we lay was, as it were, a deep dungeon*, and an exceeding high and steep hill before it. Before I got to the top of the hill, I thought my heart and legs, and all would have broken, and failed me. What, through faintness and soreness of body, it was a grievous day of travel to me. [<anticipates “wilderness gothic”; compare “pit” elsewhere incl. 20.6a]

[7.1a] As we went along, I saw a place where English cattle had been. That was comfort to me, such as it was. Quickly after that we came to an English path, which so took with me, that I thought I could have freely lyen [lain] down and died.

[7.1b] That day, a little after noon, we came to Squakeag, where the Indians quickly spread themselves over the deserted English fields, gleaning what they could find. Some picked up ears of wheat that were crickled [cracked, crackled] down; some found ears of Indian corn; some found ground nuts, and others sheaves of wheat that were frozen together in the shock [bundle, stack], and went to threshing of them out. Myself got two ears of Indian corn, and whilst I did but turn my back, one of them was stolen from me, which much troubled me.

[7.1c] There came an Indian to them at that time with a basket of horse liver. I asked him to give me a piece. "What," says he, "can you eat horse liver?" I told him, I would try, if he would give a piece, which he did, and I laid it on the coals to roast. But before it was half ready they [some Indians] got half of it away from me, so that I was fain to take the rest and eat it as it was, with the blood about my mouth, and yet a savory bit it was to me: "For to the hungry soul every bitter thing is sweet." A solemn sight methought it was, to see fields of wheat and Indian corn forsaken and spoiled and the remainders of them to be food for our merciless enemies. That night we had a mess [meal, as in “mess hall”] of wheat for our supper.

![]()

|

from The Eighth Remove |

contemporary English drawing of Indian leader of King Philip's War (His Indian name: Metacom or Metacomet, 2nd son of Massasoit, Wampanoag leader who joined Pilgrims for "First Thanksgiving") |

[8.1] On the morrow morning we must go over the river, i.e. Connecticut, to meet with King Philip [Metacomet, the Wampanoag war chief]. . . . But as my foot was upon the canoe to step in there was a sudden outcry among them, and I must step back, and instead of going over the river, I must go four or five miles up the river farther northward. Some of the Indians ran one way, and some another. The cause of this rout [disorder, retreat] was, as I thought, their espying [catching sight of] some English scouts, who were thereabout. In this travel up the river about noon the company made a stop, and sat down; some to eat, and others to rest them.

[8.1a] As I sat amongst them, musing of things past, my son Joseph unexpectedly came to me. We asked of each other's welfare, bemoaning our doleful condition, and the change that had come upon us. We had husband and father, and children, and sisters, and friends, and relations, and house, and home, and many comforts of this life: but now we may say, as Job, "Naked came I out of my mother's womb, and naked shall I return: the Lord gave, the Lord hath taken away, blessed be the name of the Lord."

[8.1b] I asked him [son Joseph] whether he would read. He told me he earnestly desired it, I gave him my Bible, and he lighted upon that comfortable Scripture "I shall not die but live, and declare the works of the Lord: the Lord hath chastened me sore yet he hath not given me over to death" (Psalm 118.17-18). "Look here, mother," says he, "did you read this?" And here I may take occasion to mention one principal ground of my setting forth these lines: even as the psalmist says, to declare the works of the Lord, and His wonderful power in carrying us along, preserving us in the wilderness, while under the enemy's hand, and returning of us in safety again. And His goodness in bringing to my hand so many comfortable and suitable scriptures in my distress.

[8.1c] But to return, we traveled on till night; and in the morning, we must go over the river to Philip's crew [warriors]. When I was in the canoe I could not but be amazed at the numerous crew [gathering] of pagans that were on the bank on the other side. When I came ashore, they gathered all about me, I sitting alone in the midst. I observed they asked one another questions, and laughed, and rejoiced over their gains and victories.

[8.1d] Then my heart began to fail: and I fell aweeping, which was the first time to my remembrance, that I wept before them. Although I had met with so much affliction, and my heart was many times ready to break, yet could I not shed one tear in their sight; but rather had been all this while in a maze [anticipates the gothic maze or labyrinth, mirrored in the mind], and like one astonished. But now I may say as Psalm 137.1, "By the Rivers of Babylon, there we sate down: yea, we wept when we remembered Zion."

[8.1e] There one of them asked me why I wept. I could hardly tell what to say: Yet I answered, they would kill me. "No," said he, "none will hurt you." Then came one of them and gave me two spoonfuls of meal to comfort me, and another gave me half a pint of peas; which was more worth than many bushels at another time.

[8.1f] Then I went to see King Philip. He bade me come in and sit down, and asked me whether I would smoke it [a pipe of tobacco] (a usual compliment nowadays amongst saints and sinners) but this no way suited me. For though I had formerly used tobacco, yet I had left it ever since I was first taken [captive] [another change]. It seems to be a bait [temptation] the devil lays to make men lose their precious time. I remember with shame how formerly, when I had taken two or three pipes, I was presently ready for another, such a bewitching thing it is. But I thank God, He has now given me power over it; surely there are many who may be better employed than to lie sucking a stinking tobacco-pipe.

[8.2] Now the Indians gather their forces to go against Northampton. Over night one went about yelling and hooting to give notice of the design. Whereupon they fell to boiling of ground nuts, and parching of corn (as many as had it) for their provision; and in the morning away they went.

[8.2a] During my abode in this place, Philip spake to me to make a shirt for his boy, which I did, for which he gave me a shilling. I offered the money to my master, but he bade me keep it; and with it I bought a piece of horse flesh. Afterwards he [Philip or Quinnapin?] asked me to make a cap for his boy, for which he invited me to dinner. I went, and he gave me a pancake, about as big as two fingers. It was made of parched wheat, beaten, and fried in bear's grease, but I thought I never tasted pleasanter meat [solid food] in my life. There was a squaw who spake to me to make a shirt for her sannup [husband], for which she gave me a piece of bear. Another asked me to knit a pair of stockings, for which she gave me a quart of peas.

[8.2b] I boiled my peas and bear together, and invited my master and mistress to dinner; but the proud gossip [wife], because I served them both in one dish, would eat nothing, except one bit that he gave her upon the point of his knife. [Mary may violate a serving protocol, which Quinnapin circumvents to keep peace among the women of his extended household. Compare 14.1]

[8.2c] Hearing that my son was come to this place, I went to see him, and found him lying flat upon the ground. I asked him how he could sleep so? He answered me that he was not asleep, but at prayer; and lay so, that they might not observe what he was doing. I pray God he may remember these things now he is returned in safety. . . .

[8.3] The Indians returning from Northampton, brought with them some horses, and sheep, and other things which they had taken . . .

![]()

|

from The Ninth Remove |

ground nuts |

[9.1] But instead of going either to Albany or homeward, we must go five miles up the river, and then go over it. Here we abode a while. Here lived a sorry Indian, who spoke to me to make him a shirt. When I had done it, he would pay me nothing. But he living by the riverside, where I often went to fetch water, I would often be putting of him in mind, and calling for my pay: At last he told me if I would make another shirt, for a papoose not yet born, he would give me a knife, which he did when I had done it.

[9.1a] I carried the knife in, and my master asked me to give it him, and I was not a little glad that I had anything that they would accept of, and be pleased with. When we were at this place, my master's maid came home; she had been gone three weeks into the Narragansett country to fetch corn [the Narragansetts, a powerful New England tribe, were allies of King Philip], where they had stored up some in the ground.

[9.1b] She brought home about a peck and half [3 gallons] of corn. This was about the time that their great captain, Naananto, was killed in the Narragansett country. My son being now about a mile from me, I asked liberty to go and see him; they bade me go, and away I went; but quickly lost myself, traveling over hills and through swamps, and could not find the way to him.

[9.1c] And I cannot but admire at the wonderful power and goodness of God to me, in that, though I was gone from home, and met with all sorts of Indians, and those I had no knowledge of, and there being no Christian soul near me; yet not one of them offered the least imaginable miscarriage [misconduct] to me*. [*compare 20.5a below; New England Indians did not customarily abuse female captives sexually.]

[9.1d] I turned homeward again, and met with my master. He showed me the way to my son. When I came to him I found him not well: and withall he had a boil on his side, which much troubled him. We bemoaned one another a while, as the Lord helped us, and then I returned again. When I was returned, I found myself as unsatisfied as I was before. I went up and down mourning and lamenting; and my spirit was ready to sink with the thoughts of my poor children. My son was ill, and I could not but think of his mournful looks, and no Christian friend was near him, to do any office of love for him, either for soul or body. And my poor girl, I knew not where she was, nor whether she was sick, or well, or alive, or dead. I repaired under these thoughts to my Bible (my great comfort in that time) and that Scripture came to my hand, "Cast thy burden upon the Lord, and He shall sustain thee" (Psalm 55.22).

[9.2] But I was fain to go and look after [for] something to satisfy my hunger, and going among the wigwams, I went into one and there found a squaw who showed herself very kind to me, and gave me a piece of bear. I put it into my pocket, and came home, but could not find an opportunity to broil it, for fear they would get it from me, and there it lay all that day and night in my stinking pocket. In the morning I went to the same squaw, who had a kettle of ground nuts boiling. I asked her to let me boil my piece of bear in her kettle, which she did, and gave me some ground nuts to eat with it: and I cannot but think how pleasant it was to me. I have sometime seen bear baked very handsomely among the English, and some like it, but the thought that it was bear made me tremble. But now that was savory to me that one would think was enough to turn the stomach of a brute creature. . . .

![]()

|

from The Tenth Remove |

|

[10.1] That day a small part of the company Removed about three-quarters of a mile, intending further the next day. When they came to the place where they intended to lodge, and had pitched their wigwams, being hungry, I went again back to the place we were before at, to get something to eat, being encouraged by the squaw's kindness, who bade me come again. When I was there, there came an Indian to look after me, who when he had found me, kicked me all along. I went home and found venison [deer] roasting that night, but they would not give me one bit of it. Sometimes I met with favor, and sometimes with nothing but frowns.

![]()

|

from The Eleventh Remove |

|

[11.1] The next day in the morning they [Indians] took their travel, intending a day's journey up the river. I took my load at my back, and quickly we came to wade over the river; and passed over tiresome and wearisome hills. One hill was so steep that I was fain to creep up upon my knees, and to hold by the twigs and bushes to keep myself from falling backward. My head also was so light that I usually reeled as I went; but I hope all these wearisome steps that I have taken, are but a forewarning to me of the heavenly rest: "I know, O Lord, that thy judgments are right, and that thou in faithfulness hast afflicted me" (Psalm 119.75).

![]()

|

from The Twelfth Remove |

wigwam |

[12.1] It was upon a Sabbath-day-morning, that they prepared for their travel. This morning I asked my master whether he would sell me to my husband. He answered me "Nux," [= yes] which did much rejoice my spirit. My mistress, before we went, was gone to the burial of a papoose [child], and returning, she found me sitting and reading in my Bible; she snatched it hastily out of my hand, and threw it out of doors. I ran out and catched it up, and put it into my pocket, and never let her see it afterward.

[12.1a] Then they packed up their things to be gone, and gave me my load. I complained it was too heavy, whereupon she gave me a slap in the face, and bade me go; I lifted up my heart to God, hoping the redemption [purchase of freedom] was not far off; and the rather because their insolency grew worse and worse. [With all respect to Rowlandson’s stress, the passage above shows limits to her sympathy or comprehension. Her mistress’s spite towards her after “the burial of a papoose” may result from associating the presence of white settlers like Rowlandson and their belief system represented by the Bible with the child’s death and her people’s general suffering. Is Rowlandson therefore an “unreliable narrator?”]

[12.2] But the thoughts of my going homeward (for so we bent our course) much cheered my spirit, and made my burden seem light, and almost nothing at all. But (to my amazement and great perplexity) the scale was soon turned; for when we had gone a little way, on a sudden my mistress gives out; she would go no further, but turn back again, and said I must go back again with her, and she called her sannup [husband], and would have had him gone back also, but he would not, but said he would go on, and come to us again in three days.

[12.2a] My spirit was, upon this, I confess, very impatient, and almost outrageous. I thought I could as well have died as went back; I cannot declare the trouble that I was in about it; but yet back again I must go. As soon as I had the opportunity, I took my Bible to read, and that quieting Scripture came to my hand, "Be still, and know that I am God" (Psalm 46.10). Which stilled my spirit for the present. But a sore time of trial, I concluded, I had to go through, my master being gone, who seemed to me the best friend that I had of an Indian, both in cold and hunger, and quickly so it proved.

[12.2b] Down I sat, with my heart as full as it could hold, and yet so hungry that I could not sit neither; but going out to see what I could find, and walking among the trees, I found six acorns, and two chestnuts, which were some refreshment to me. Towards night I gathered some sticks [firewood] for my own comfort, that I might not lie a-cold; but when we came to lie down they bade me to go out, and lie somewhere else, for they had company (they said) come in more than their own. I told them, I could not tell [guess] where to go, they bade me go look; I told them, if I went to another wigwam they would be angry, and send me home again.

[12.2c] Then one of the company drew his sword, and told me he would run me through if I did not go presently [right away]. Then was I fain to stoop to this rude fellow, and to go out in the night, I knew not whither. Mine eyes have seen that fellow afterwards walking up and down Boston, under the appearance of a Friend Indian, and several others of the like cut. I went to one wigwam, and they told me they had no room. Then I went to another, and they said the same; at last an old Indian bade me to come to him, and his squaw gave me some ground nuts; she gave me also something to lay under my head, and a good fire we had; and through the good providence of God, I had a comfortable lodging that night. [Rowlandson attributes her comfort to God rather than the old Indian’s hospitality] . . . .

![]()

|

from The Thirteenth Remove |

|

[13.1] Instead of going toward the [Massachusetts] Bay [where her husband is], which was that I desired, I must go with them five or six miles down the river into a mighty thicket of brush; where we abode almost a fortnight. . . . About this time they came yelping from Hadley, where they had killed three Englishmen, and brought one captive with them, viz. Thomas Read. They all gathered about the poor man, asking him many questions.

[13.1a] I desired also to go and see him; and when I came, he was crying bitterly, supposing they would quickly kill him. Whereupon I asked one of them, whether they intended to kill him; he answered me, they would not. [Rowlandson serves as mediator or interpreter between two cultures?]

[13.1b] He being a little cheered with that, I asked him about the welfare of my husband. He told me he saw him such a time in the Bay, and he was well, but very melancholy [depressed]. By which I certainly understood (though I suspected it before) that whatsoever the Indians told me respecting him was vanity and lies. Some of them told me he [her husband] was dead, and they had killed him; some said he was married again, and that the Governor wished him to marry; and told him he should have his choice, and that all persuaded I was dead. So like were these barbarous creatures to him who was a liar from the beginning. [<Satan] . . .

[13.2] Then my son came to see me, and I asked his master to let him stay awhile with me, that I might comb his head, and look over him, for he was almost overcome with lice. . . . [I]t seems [he] tarried a little too long; for his master was angry with him, and beat him, and then sold him. Then he came running to tell me he had a new master, and that he had given him some ground nuts already. Then I went along with him to his new master who told me he loved him, and he should not want. So his master carried him away, and I never saw him afterward, till I saw him at Piscataqua in Portsmouth. [a touching “Mom” errand]

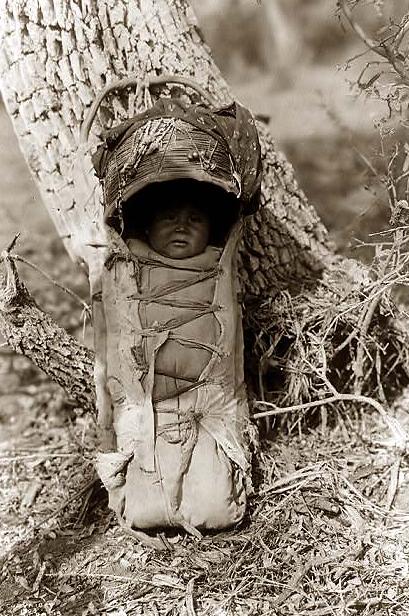

[13.3] That night they bade me go out of the wigwam again. My mistress's papoose was sick, and it died that night, and there was one benefit in it—that there was more room. [Compare Rowlandson’s insensitivity to the Indians’ insensitivity to her daughter’s suffering in 2.1b above] I went to a wigwam, and they bade me come in, and gave me a skin to lie upon, and a mess of venison [dish of deer meat] and ground nuts, which was a choice dish among them. On the morrow they buried the papoose, and afterward, both morning and evening, there came a company to mourn and howl with her; though I confess I could not much condole with them. . . .

![]()

|

from The Fourteenth Remove |

papoose |

[14.1] Now must we pack up and be gone from this thicket, bending our course toward the Baytowns; . . . When night came on we sat down; it rained, but they quickly got up a bark wigwam, where I lay dry that night. I looked out in the morning, and many of them had lain in the rain all night, I saw by their reeking. Thus the Lord dealt mercifully with me many times, and I fared better than many of them. In the morning they took the blood of the deer, and put it into the paunch, and so boiled it. I could eat nothing of that, though they ate it sweetly. And yet they were so nice in other things, that when I had fetched water, and had put the dish I dipped the water with into the kettle of water which I brought, they would say they would knock me down; for they said, it was a sluttish trick. [As in 8.2b, Rowlandson has violated an Indian protocol or etiquette; her attention to such details provides valuable anthropological information]

![]()

from The Fifteenth Remove |

Algonquian canoe |

[15.1] We went on our travel. I having got one handful of ground nuts, for my support that day, they gave me my load, and I went on cheerfully (with the thoughts of going homeward), having my burden more on my back than my spirit. We came to Banquang river again that day, near which we abode a few days.

[15.1a] Sometimes one of them would give me a pipe, another a little tobacco, another a little salt: which I would change for a little victuals. I cannot but think what a wolvish appetite persons have in a starving condition; for many times when they gave me that which was hot, I was so greedy, that I should burn my mouth, that it would trouble me hours after, and yet I should quickly do the same again. And after I was thoroughly hungry, I was never again satisfied. For though sometimes it fell out, that I got enough, and did eat till I could eat no more, yet I was as unsatisfied as I was when I began. And now could I see that Scripture verified (there being many Scriptures which we do not take notice of, or understand till we are afflicted) "Thou shalt eat and not be satisfied" (Micah 6.14). . . .

![]()

from The Sixteenth Remove |

|

[16.1] We began this Remove with wading over Banquang river: the water was up to the knees, and the stream very swift, and so cold that I thought it would have cut me in sunder. . . . The Indians stood laughing to see me staggering along; but in my distress the Lord gave me experience of the truth, and goodness of that promise, "When thou passest through the waters, I will be with thee; and through the rivers, they shall not overflow thee" (Isaiah 43.2). Then I sat down to put on my stockings and shoes, with the tears running down mine eyes, and sorrowful thoughts in my heart, but I got up to go along with them.

[16.1b] Quickly there came up to us an Indian, who informed them that I must go to Wachusett to my master, for there was a letter come from the council to the Sagamores [Indian chieftains], about redeeming [ransoming] the captives, and that there would be another in fourteen days, and that I must be there ready. My heart was so heavy before that I could scarce speak or go in the path; and yet now so light, that I could run. . . .

![]()

from The Seventeenth Remove |

|

[17.1] A comfortable Remove it was to me, because of my hopes. They gave me a pack, and along we went cheerfully; but quickly my will proved more than my strength; having little or no refreshing, my strength failed me, and my spirits were almost quite gone. . . .

[17.1a] At night we came to an Indian town, and the Indians sat down by a wigwam discoursing, but I was almost spent, and could scarce speak. I laid down my load, and went into the wigwam, and there sat an Indian boiling of horses’ feet (they being wont [accustomed] to eat the flesh first, and when the feet were old and dried, and they had nothing else, they would cut off the feet and use them). I asked him to give me a little of his broth, or water they were boiling in; he took a dish, and gave me one spoonful of samp [dried corn], and bid me take as much of the broth as I would. Then I put some of the hot water to the samp, and drank it up, and my spirit came again. . . .

![]()

from The Eighteenth Remove |

Algonquian village |

[18.1] We took up our packs and along we went, but a wearisome day I had of it. As we went along I saw an Englishman stripped naked, and lying dead upon the ground, but knew not who it was. Then we came to another Indian town, where we stayed all night. In this town there were four English children, captives; and one of them my own sister's. I went to see how she did, and she was well, considering her captive condition. I would have tarried [lingered] that night with her, but they that owned her would not suffer [allow] it. . . .

[18.1a] Then I went to another wigwam, where there were two of the English children; the squaw was boiling horses feet; then she cut me off a little piece, and gave one of the English children a piece also. Being very hungry I had quickly eat up mine, but the child could not bite it, it was so tough and sinewy, but lay sucking, gnawing, chewing and slabbering of it in the mouth and hand. Then I took it of the child, and eat it myself, and savory it was to my taste.

[18.1b] Then I may say as Job 6.7, "The things that my soul refused to touch are as my sorrowful meat." Thus the Lord made that pleasant refreshing, which another time would have been an abomination.

[18.1c] Then I went home to my mistress's wigwam; and they told me I disgraced my master with begging, and if I did so any more, they would knock me in the head. I told them, they had as good knock me in head as starve me to death.

![]()

from The Nineteenth Remove |

Mt. Wachuset (see 19.1) |

[19.1] They said, when we went out, that we must travel to Wachusett [see 16.1] this day. But a bitter weary day I had of it, traveling now three days together, without resting any day between. At last, after many weary steps, I saw Wachusett hills, but many miles off. Then we came to a great swamp, through which we traveled, up to the knees in mud and water, which was heavy going to one tired before. Being almost spent, I thought I should have sunk down at last, and never got out; but I may say, as in Psalm 94.18, "When my foot slipped, thy mercy, O Lord, held me up."

[19.1a] Going along, having indeed my life, but little spirit, [King] Philip*, who was in the company, came up and took me by the hand, and said, two weeks more and you shall be mistress [restored to her husband] again. I asked him, if he spake true? He answered, "Yes, and quickly [sooner] you shall come to your master [Quinnapin] again; who had been gone from us three weeks." [King Philip = Wampanoag war leader Metacomet]

[19.1b] After many weary steps we came to Wachusett, where he [Quinnapin, her Indian master] was: and glad I was to see him. He asked me, when I washed me? I told him not this month. Then he fetched me some water himself, and bid me wash, and gave me the glass [mirror] to see how I looked; and bid his squaw give me something to eat. So she gave me a mess [dish] of beans and meat, and a little ground nut cake. I was wonderfully revived with this favor showed me: "He made them also to be pitied of all those that carried them captives" (Psalm 106.46). [Rowlandson attributes Quinnapin’s care to God’s command, but her master may be motivated also by courtesy (which he shows elsewhere) and to have her look well for a ransom exchange, which would affect his prestige and his payment]

[19.2] My master had three squaws [Indian wives], living sometimes with one, and sometimes with another one, this old squaw, at whose wigwam I was, and with whom my master had been those three weeks. Another was Wattimore [Weetamoo] with whom I had lived and served all this while. A severe and proud dame she was, bestowing every day in dressing herself neat as much time as any of the gentry of the land: powdering her hair, and painting her face, going with necklaces, with jewels in her ears, and bracelets upon her hands. When she had dressed herself, her work was to make girdles of wampum and beads. The third squaw was a younger one, by whom he had two papooses.

[19.2a] By the time I was refreshed by the old squaw, with whom my master was, Weetamoo's maid came to call me home [to Weetamoo’s wigwam], at which I fell aweeping. Then the old squaw told me, to encourage me, that if I wanted victuals, I should come to her, and that I should lie there in her wigwam. Then I went with the maid, and quickly came again and lodged there. The squaw laid a mat under me, and a good rug over me; the first time I had any such kindness showed me.

[19.2b] I understood that Weetamoo thought that if she should let me go and serve with the old squaw, she would be in danger to lose not only my service, but the redemption pay also. . . . Then came an Indian, and asked me to knit him three pair of stockings, for which I had a hat, and a silk handkerchief. Then another asked me to make her a shift, for which she gave me an apron.

[19.3] Then came Tom and Peter [Praying Indians], with the second letter from the council, about the captives. Though they were Indians, I got them by the hand, and burst out into tears. My heart was so full that I could not speak to them; but recovering myself, I asked them how my husband did, and all my friends and acquaintance? They said, "They are all very well but melancholy."

[19.3a] They brought me two biscuits, and a pound of tobacco. The tobacco I quickly gave away. When it was all gone, one [Indian] asked me to give him a pipe of tobacco. I told him it was all gone. Then began he to rant and threaten. I told him when my husband came I would give him some. Hang him rogue (says he) I will knock out his brains, if he comes here. And then again, in the same breath they would say that if there should come an hundred without guns, they would do them no hurt. So unstable and like madmen they were. [compare to images of terrorists] . . .

[19.3b] When the letter was come, the Sagamores met to consult about the captives, and called me to them to inquire how much my husband would give to redeem me. When I came I sat down among them, as I was wont to do, as their manner is. Then they bade me stand up, and said they were the General Court. [Rowlandson imitates Indian manners, but the Indians imitate English manners]

[19.3c] They bid me speak what I thought he [husband] would give [for ransom]. Now knowing that all we had was destroyed by the Indians, I was in a great strait [tight spot]. I thought if I should speak of but a little it would be slighted, and hinder the matter; if of a great sum, I knew not where it would be procured. Yet at a venture I said "Twenty pounds," yet desired them to take less. But they would not hear of that [asking for less], but sent that message to Boston, that for twenty pounds I should be redeemed.

[19.3d] It was a Praying Indian that wrote their letter for them. [Praying Indians were trained to read and write; Rowlandson’s following remarks shows the English mistrust of missionary efforts] . . . There was another Praying Indian, who when he had done all the mischief that he could, betrayed his own father into the English hands, thereby to purchase his own life. Another Praying Indian was at Sudbury fight, though, as he deserved, he was afterward hanged for it. There was another Praying Indian, so wicked and cruel, as to wear a string about his neck, strung with Christians' fingers. Another Praying Indian, when they went to Sudbury fight, went with them, and his squaw also with him, with her papoose at her back.

[19.3e-g provide an invaluable record of an Indian war ceremony.]

[19.3e] Before they went to that fight they got a company together to pow-wow. The manner was as followeth: there was one that kneeled upon a deerskin, with the company round him in a ring who kneeled, and striking upon the ground with their hands, and with sticks, and muttering or humming with their mouths. Besides him who kneeled in the ring, there also stood one with a gun in his hand. Then he on the deerskin made a speech, and all manifested assent to it; and so they did many times together.

[19.3f] Then they bade him with the gun go out of the ring, which he did. But when he was out, they called him in again; but he seemed to make a stand; then they called the more earnestly, till he returned again. Then they all sang. Then they gave him two guns, in either hand one. And so he on the deerskin began again; and at the end of every sentence in his speaking, they all assented, humming or muttering with their mouths, and striking upon the ground with their hands.

[19.3g] Then they bade him with the two guns go out of the ring again; which he did, a little way. Then they called him in again, but he made a stand. So they called him with greater earnestness; but he stood reeling and wavering as if he knew not whither he should stand or fall, or which way to go. Then they called him with exceeding great vehemency, all of them, one and another. After a little while he turned in, staggering as he went, with his arms stretched out, in either hand a gun. As soon as he came in they all sang and rejoiced exceedingly a while. And then he upon the deerskin, made another speech unto which they all assented in a rejoicing manner. And so they ended their business, and forthwith went to Sudbury fight. [The war-ceremony observed by Rowlandson represents the Indian warriors apparently dying but then surviving]

[19.3h] To my thinking they went without any scruple [question], but that they should prosper, and gain the victory. And they went out not so rejoicing, but they came home with as great a victory. For they said they had killed two captains and almost an hundred men. One Englishman they brought along with them: and he said, it was too true, for they had made sad work at Sudbury, as indeed it proved. Yet they came home without that rejoicing and triumphing over their victory which they were wont to show at other times; but rather like dogs (as they say) which have lost their ears. Yet I could not perceive that it was for their own loss of men. They said they had not lost above five or six; and I missed none, except in one wigwam. When they went [left for battle], they acted as if the devil had told them that they should gain the victory; and now they acted as if the devil had told them they should have a fall. Whither it were so or no, I cannot tell, but so it proved, for quickly they began to fall, and so held on that summer, till they came to utter ruin. They came home on a Sabbath day, and the Powaw [priest] that kneeled upon the deer-skin came home (I may say, without abuse) as black as the devil. . . . [<gothic color & moral code]

![]()

from The Twentieth Remove |

Redemption Rock, where Rowlandson was exchanged |

[20.1] It was their [Indians’] usual manner to Remove, when they had done any mischief, lest they should be found out; and so they did at this time. We went about three or four miles, and there they built a great wigwam, big enough to hold an hundred Indians, which they did in preparation to a great day of dancing. . . . The Indians now began to come from all quarters, against [to join] their merry dancing day. . . . They made use of their tyrannical power whilst they had it; but through the Lord's wonderful mercy, their time was now but short.

[20.2] On a Sabbath day, the sun being about an hour high in the afternoon, came Mr. John Hoar (the council permitting him, and his own foreward [brave] spirit inclining him), together with the two forementioned Indians, Tom and Peter, with their third letter from the council. When they came near, I was abroad [elsewhere]. Though I saw them not, they presently called me in, and bade me sit down and not stir. . . .

[20.2a] When they had talked their fill with him [Hoar the Englishman], they suffered me to go to him. We asked each other of our welfare, and how my husband did, and all my friends? He told me they were all well, and would be glad to see me. Amongst other things which my husband sent me, there came a pound of tobacco, which I sold for nine shillings in money . . . .

[20.2b] In the morning Mr. Hoar invited the Sagamores [Indian leaders] to dinner; but when we went to get it ready we found that they [other Indians] had stolen the greatest part of the provision Mr. Hoar had brought, out of his bags, in the night. . . . But instead of doing us any mischief, they seemed to be ashamed of the fact, and said, it were some matchit [misbehaving ] Indian that did it. . . .

[20.2c] Mr. Hoar called them betime [early] to dinner, but they ate very little, they being so busy in dressing themselves, and getting ready for their dance, which was carried on by eight of them, four men and four squaws. My master and mistress being two. He was dressed in his holland shirt, with great laces sewed at the tail of it; he had his silver buttons, his white stockings, his garters were hung round with shillings, and he had girdles of wampum upon his head and shoulders. She had a kersey [woolen] coat, and covered with girdles of wampum from the loins upward. Her arms from her elbows to her hands were covered with bracelets; there were handfuls of necklaces about her neck, and several sorts of jewels in her ears. She had fine red stockings, and white shoes, her hair powdered and face painted red, that was always before black. And all the dancers were after the same manner.

[20.2d] There were two others singing and knocking on a kettle for their music. They kept hopping up and down one after another, with a kettle of water in the midst, standing warm upon some embers, to drink of when they were dry. They held on till it was almost night, throwing out wampum to the standers by. [wampum served as money and ornament; Quinnapin above wears English shillings]

[20.2e] At night I asked them again, if I should go home? They all as one said no, except my husband would come for me. When we were lain down, my master went out of the wigwam, and by and by sent in an Indian called James the Printer*, who told Mr. Hoar, that my master would let me go home tomorrow, if he would let him have one pint of liquors. Then Mr. Hoar called his own Indians, Tom and Peter, and bid them go and see whether he would promise it before them three . . . [*James the Printer attended Harvard College and helped the missionary John Eliot print his translation of the Bible in a local Indian language]

[20.2f] My master after he had had his drink, quickly came ranting into the wigwam again, and called for Mr. Hoar, drinking to him, and saying, he was a good man, and then again he would say, "hang him rogue." Being almost drunk, he would drink to him, and yet presently say he should be hanged. Then he called for me. I trembled to hear him, yet I was fain to go to him, and he drank to me, showing no incivility. He was the first Indian I saw drunk all the while that I was amongst them. At last his squaw ran out, and he after her, round the wigwam, with his money jingling at his knees. But she escaped him. But having an old squaw he ran to her; and so through the Lord's mercy, we were no more troubled that night. . . .

[20.3] On Tuesday morning they called their general court (as they call it) to consult and determine, whether I should go home or no. And they all as one man did seemingly consent to it, that I should go home; except Philip, who would not come among them. [<evidence of dissension among the war-weary Indians?]

[20.4] But before I go any further, I would take leave to mention a few remarkable passages of providence, which I took special notice of in my afflicted time. [again Rowlandson carefully criticizes the English militia for not finding ways to rescue her sooner by engaging the Indians, which she resolves by attributing the Indians’ survival and her suffering to the will of God]

1. Of the fair opportunity lost in the long march, a little after the fort fight, when our English army was so numerous, and in pursuit of the enemy, and so near as to take several and destroy them, and the enemy in such distress for food that our men might track them by their rooting in the earth for ground nuts, whilst they were flying for their lives. . . .

2. I cannot but remember how the Indians derided the slowness, and dullness of the English army, in its setting out. . . . "It may be they will come in May," said they. Thus did they scoff at us, as if the English would be a quarter of a year getting ready.

3. Which also I have hinted before, when the English army with new supplies were sent forth to pursue after the enemy, and they understanding it, fled before them till they came to Banquang river, where they forthwith went over safely; that that river should be impassable to the English. I can but admire [marvel] to see the wonderful providence of God in preserving the heathen for further affliction to our poor country. [<the only reason God lets the Indians survive is to keep the English from feeling overly secure in God’s blessings; see #4 below] They could go in great numbers over, but the English must stop. God had an over-ruling hand in all those things.

4. It was thought, if their corn were cut down, they [the Indians] would starve and die with hunger, and all their corn that could be found, was destroyed, and they driven from that little they had in store, into the woods in the midst of winter; and yet how to admiration did the Lord preserve them for His holy ends, and the destruction of many still amongst the English! strangely did the Lord provide for them; that I did not see (all the time I was among them) one man, woman, or child, die with hunger. [Rowlandson has reasons not to like the Indians, but it’s possible to attribute the Indians’ survival to their own toughness and ingenuity rather than the will of the English God] . . .

The chief and commonest food was ground nuts. They eat also nuts and acorns, artichokes, lilly roots, ground beans, and several other weeds and roots, that I know not.

They would pick up old bones, and cut them to pieces at the joints, and if they were full of worms and maggots, they would scald them over the fire to make the vermine come out, and then boil them, and drink up the liquor, and then beat the great ends of them in a mortar, and so eat them. They would eat horse's guts, and ears, and all sorts of wild birds which they could catch; also bear, venison, beaver, tortoise, frogs, squirrels, dogs, skunks, rattlesnakes; yea, the very bark of trees; besides all sorts of creatures, and provision which they plundered from the English. I can but stand in admiration to see the wonderful power of God in providing for such a vast number of our enemies in the wilderness, where there was nothing to be seen, but from hand to mouth. Many times in a morning, the generality of them would eat up all they had, and yet have some further supply against they wanted. It is said, "Oh, that my People had hearkened to me, and Israel had walked in my ways, I should soon have subdued their Enemies, and turned my hand against their Adversaries" (Psalm 81.13-14). But now our perverse and evil carriages in the sight of the Lord, have so offended Him, that instead of turning His hand against them, the Lord feeds and nourishes them up to be a scourge to the whole land.

5. Another thing that I would observe is the strange providence of God, in turning things about when the Indians was at the highest, and the English at the lowest. I was with the enemy eleven weeks and five days, and not one week passed without the fury of the enemy, and some desolation by fire and sword upon one place or other. They mourned (with their black faces [Indians smeared ash on their faces in mourning]) for their own losses, yet triumphed and rejoiced in their inhumane, and many times devilish cruelty to the English. They would boast much of their victories; saying that in two hours time they had destroyed such a captain and his company at such a place; and boast how many towns they had destroyed, and then scoff, and say they had done them a good turn to send them to Heaven so soon. . . . and though they had made a pit, in their own imaginations, as deep as hell for the Christians that summer, yet the Lord hurled themselves into it. [the “pit” of hell later reappears secularized as a gothic set-piece in Edgar Huntly and Poe] . . .

[20.5] But to return again to my going home, where we may see a remarkable change of providence. At first they were all against it, except my husband would come for me, but afterwards they assented to it, and seemed much to rejoice in it; some asked me to send them some bread, others some tobacco, others shaking me by the hand, offering me a hood and scarfe to ride in; not one moving hand or tongue against it. Thus hath the Lord answered my poor desire, and the many earnest requests of others put up unto God for me. . . .

[20.5a] And now God hath granted me my desire. O the wonderful power of God that I have seen, and the experience that I have had. I have been in the midst of those roaring lions, and savage bears [Indians = inhuman beasts], that feared neither God, nor man, nor the devil, by night and day, alone and in company, sleeping all sorts together, and yet not one of them ever offered me the least abuse of unchastity to me, in word or action. Though some are ready to say I speak it for my own credit; but I speak it in the presence of God, and to His Glory. . . . [compare 9.1c above; New England Indians did not customarily abuse female captives sexually.]

[20.5b] So I took my leave of them, and in coming along my heart melted into tears, more than all the while I was with them, and I was almost swallowed up with the thoughts that ever I should go home again. About the sun going down, Mr. Hoar, and myself, and the two Indians came to Lancaster [hometown], and a solemn sight it was to me. There had I lived many comfortable years amongst my relations and neighbors, and now not one Christian to be seen, nor one house left standing.

[20.5c] We went on to a farmhouse that was yet standing, where we lay all night, and a comfortable lodging we had, though nothing but straw to lie on. The Lord preserved us in safety that night, and raised us up again in the morning, and carried us along, that before noon, we came to Concord. [Concord = Massachusetts town, pronounced “conquered”; a century later, site of first battle of Revolutionary War, and in 1800s the residence or birthplace of Emerson, Hawthorne, the Alcotts, and Thoreau]

[20.5d] Now was I full of joy, and yet not without sorrow; joy to see such a lovely sight, so many Christians together, and some of them my neighbors. There I met with my brother, and my brother-in-law, who asked me, if I knew where his wife was? Poor heart! he had helped to bury her, and knew it not. She being shot down by the house was partly burnt, so that those who were at Boston at the desolation of the town, and came back afterward, and buried the dead, did not know her.