|

Craig White's authors |

|

Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810) |

|

Brown's early and continuing importance to American literary history:

Charles Brockden Brown grew up during the American Revolution and attempted to become the first American citizen to make a career as a professional novelist.

1799-1800: Brown wrote and published eight novels. Modest sales could not support a continuing career, but several gained critical praise and wide readership among the Trans-Atlantic intelligentsia, leading to their re-publication throughout the Romantic era.

The imaginative, intellectual, and psychological depth

of these novels influenced fiction writers

of the next generation like Edgar Allan Poe (The Fall of the House of Usher,

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym)

and Mary Shelley (

Brown is best remembered for helping develop a distinctly American national literature in two ways:

![]() Brown adapted European

styles or genres like the

Gothic, the sensation

novel, the seduction novel, and the sentimental romance to American settings and

scenarios; e.g., the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in Arthur

Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 (1799-1800); or relocating

gothic settings from European castles to the

American wilderness in

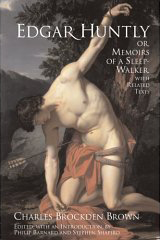

Edgar

Huntly; or Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker (1799).

Brown adapted European

styles or genres like the

Gothic, the sensation

novel, the seduction novel, and the sentimental romance to American settings and

scenarios; e.g., the 1793 yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in Arthur

Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 (1799-1800); or relocating

gothic settings from European castles to the

American wilderness in

Edgar

Huntly; or Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker (1799).

![]() Brown

developed distinctly American genres like the

Indian Captivity Narrative in fiction, as in

chapters 17-19 of

Edgar

Huntly; or Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker (1799). The captivity narrative became a

common sub-genre in American fiction, as in James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans

(1826) and twentieth-century movies like The Searchers (1956),

Little Big Man (1970), and Dances with Wolves (1990).

Brown

developed distinctly American genres like the

Indian Captivity Narrative in fiction, as in

chapters 17-19 of

Edgar

Huntly; or Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker (1799). The captivity narrative became a

common sub-genre in American fiction, as in James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans

(1826) and twentieth-century movies like The Searchers (1956),

Little Big Man (1970), and Dances with Wolves (1990).

Brown's style is also notable for his development of an unreliable narrator. For example, Edgar Huntly's narration of events often appears more wishful than accurate, and Clithero Edny's account of his life in Europe seems altogether incredible on its face, even though Edgar is inclined to believe him.

![]()

Novels and other writings by Charles Brockden Brown

Alcuin: A Dialogue (1798; reprinted in the Philadelphia Weekly Magazine as "The Rights of Women")

Sky-Walk; or the Man Unknown to Himself (1797; advertised but never published and subsequently lost)

Wieland; or, the Transformation (1798)

Memoirs of Carwin, the Biloquist (1798; incomplete)

Ormond; or, the Secret Witness (1798)

Edgar Huntly; or, Memoirs of a Sleep-Walker (1799)

Arthur Mervyn; or, Memoirs of the Year 1793 (two volumes; 1799 & 1800)

Memoirs of Steven Calvert (serialized 1799-1800)

Clara Howard; In a Series of Letters (1801)

Jane Talbot; a Novel (1801)

![]()

Biographical notes:

Born in 1771 in a Quaker family in Philadelphia, then North America's most prosperous city, Brown was the fourth of five brothers. Their father was a conveyancer or legal agent for land titles. Brown attended a Quaker Public School and showed special interests in geography. His family intended him for a career in the law. Brown's brothers developed an importing and exporting business for which Brown worked intermittently.

In preparation for a career in law, Brown apprenticed to a Philadelphia lawyer

for six years but left the practice in 1793, joining a club of progressive

intellectuals and beginning a literary career mostly by writing essays

on political and social subjects. He was

strongly influenced by the English radical-democratic writers Mary

Wollstonecraft (A Vindication of the Rights of Women, 1792) and William

Godwin (Caleb Williams, 1794), the parents of Mary Wollstonecraft

Shelley, author of

In 1799 and 1800 he wrote and published eight novels. Limited sales could not support a continuing career.

Around this time Brown began a "long courtship with Elizabett Linn, the sister of the important Presbyterian minister and writer John Blair Linn. During the four years before their marriage in 1804, Brown met continued resistance from his parents, who forbade his marriage to a non-Quaker, and from Elizabeth and her family, who had doubts about Brown's temperament, his ideas, and his income" (Elliott 267).

Additional biographical information from Emory Elliott, Revolutionary Writers: Literature and Authority in the New Republic, 1725-1810. (1986).

"In 1803 he published two important political pamphlets that attracted more public attention than anything he had previously written. . . . Even though Brown's philosophy had moved toward a more conventional view, the inflammatory positions expressed in these pamphlets are still remarkable. Because of these essays, he was suddenly regarded as an important thinker, and his ideas were debated on the floor of Congress. He had achieved status as an intellectual that he could not attain with his novels." (268)

"In the six years of marriage that followed, Brown was able to support his wife and their four children despite his continually failing health. Between 1807 and 1810 he edited The American Register, or General Repository of History, Politics and Science, a serious semiannual journal, and he began an ambitious work, A System of General Geography. He had completed a substantial amount of work on this probject, of which only the prospectus survives, when he died of tuberculosis on 22 February 1810." (269)

![]()

Critical assessments by Elliott, Revolutionary Writers (1986).

224 Each of Brown's major literary works represents another stage in his continual effort to modify and alter his fictional designs in order to win a popular audience while pleasing his demanding intellectual peers.

221-222 Most of all, Brown questioned the confidence of his age in the rational faculties of man. From a recognition of his own emotional complexity and from his serious study of human psychology . . . , Brown came to believe that it is absurd to think that people are always guided by reason and that sense experience is completely valid. The workings of passions and illusions upon the mind from within, and the operations of unfamiliar elements of the external world, can deceive humans, leading them to build elaborate logical systems and make seemingly rational decisions based upon mistaken assumptions. . . . Brown also recognized that the unconscious remained a mysterious and misunderstood aspect of experience that challenged the notion of reasonable action. He also believed that religion and the arts were necessary vehicles for expressing these deeper drives.

229 To readers who trusted in the power of human reason and the principles of divine benevolence, Brown presented a chaotic world of irrational experience and inexplicable events.

266 [Edgar] Huntly iis a character tormented by psychological impulses that are often beyond his control, and the mysterious Clithero Edny is a dangerous madman whose motives and actions defy explanation. . . . In Edgar Huntly, Brown also manipulated elements of the Indian-captivity narratives with superb results. Borrowing from these narratives which were popular with American readers for over a century, he became the first American novelist to appeal to fears and fantasies about Indians.

His use of a wilderness setting and his portraits of struggles between Huntly and his Indian enemies stand at the pivotal point in American literature between the firsthand accounts and the later [fictional] tales of Western adventure and frontier violence. James Fenimore Cooper noted his debt to Brown's innovations. That Brown was more successful in reaching a larger audience with these devices than he had been with his earlier works is acknowledged by the fact that Edgar Huntly was his most popular work and went into a second edition in 1801.

Elliott on Wieland; or, the Transformation (1798)

Adapting the formulas of the Gothic horror tale and the sentimental seduction novel [like Charlotte Temple], Brown constructed a fast-paced, suspenseful narrative containing supernatural elements, insanity, and mass murder. Perhaps to add to the appeal of the novel for those readers who had made Susanna Rowson's Charlotte: A Tale of Truth and other sentimental novels so popular in America, he chose to cast the narrative in the epistolary form and to use a woman narrator, Clara Wieland. The fairly simple plot and the enormity of Theodore Wieland's crimes should have also attracted a large reading audience. (225)

At first glance a novel of Gothic horror and sentimental romance, Wieland is also a serious intellectual document in which Brown questions some of the fundamental assumptions of his time. (234)

![]()

Sources:

"Charles Brockden Brown." Wikipedia. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

Elliott, Emory. Revolutionary Writers: Literature and Authority in the New Republic, 1725-1810. NY: Oxford UP, 1986.

Why Brown’s fiction is difficult or frustrating to read:

3a. Edgar Huntly is the first serious American attempt at "literary fiction"—written not just to sell copies or teach a lesson but to extend and influence the evolution of imaginative content and literary style. What does the novel get right and wrong? What can you learn about fiction from his successes and errors? What do you want more or less of?

![]() Romantic rhetoric archaic, florid,

extreme, intense, overloaded

Romantic rhetoric archaic, florid,

extreme, intense, overloaded

+ Quaker thees and thous

![]() Like Poe and other Romantic writers,

tendency to write in absolutes or superlatives can be tiring. Never simple

“dismay” but always “the deepest dismay”; a dark night is “unrelieved”; every

mountain is “dizzying.” (All efforts at

sublime.)

Like Poe and other Romantic writers,

tendency to write in absolutes or superlatives can be tiring. Never simple

“dismay” but always “the deepest dismay”; a dark night is “unrelieved”; every

mountain is “dizzying.” (All efforts at

sublime.)

Problems that still affect learning fiction-writers

![]() Obsessive first-person perspective,

unrelieved by alternatives; talky, shifts from one monologue to another, cf.

Frankenstein—recall Mary Shelley’s reading

Obsessive first-person perspective,

unrelieved by alternatives; talky, shifts from one monologue to another, cf.

Frankenstein—recall Mary Shelley’s reading

![]() Absence of dialogue, back-and-forth, so you're stuck in

one person's thoughts, unrelieved, for too long

Absence of dialogue, back-and-forth, so you're stuck in

one person's thoughts, unrelieved, for too long

![]() All narrative or all talk instead of mixture

of narration and dialogue as constituents of

fiction.

All narrative or all talk instead of mixture

of narration and dialogue as constituents of

fiction.

Like many first time male writers, his protagonist’s characterization is overly competent at everything, if not absolutely heroic.

[22.2] There is no one to whom I would yield the superiority in swimming [cf. Poe & Romantic rhetoric]

can shoot, endure, be totally beat up or wasted and then get up all fresh to fight again

![]() Awkwardness as story-teller—stories are

elaborately contrived, but confusions abound, along with an amateur fiction

writer’s backfilling

Awkwardness as story-teller—stories are

elaborately contrived, but confusions abound, along with an amateur fiction

writer’s backfilling

early gothic writers often hype up the scare, but then, when rationalizing what happened, become anti-climactic

![]() Reliance on coincidence

Reliance on coincidence

![]() Unclear antecedents to pronouns

Unclear antecedents to pronouns

Like many other first-time writers working on their own, he fails to vary his style in two ways:

![]() Lack of dynamics

(loud-soft, fast-slow, intense-easy)

Lack of dynamics

(loud-soft, fast-slow, intense-easy)

[chapter 22 as example of what Brown is not doing right--too many episodes, too many unrecognizable characters, hard to tell what matters and what doesn't]

cf. chapters 10 > 11 finds Clithero, then starts over

Plus we never meet potentially the best character: Queen Mab (She's referred to or told about, but she never actually appears in a scene)

How to defend reading and teaching Edgar Huntly?

An aspiring fiction writer might learn.

Readers get stretched. By reading "great literature" that isn't necessarily popular or friendly, we train our attention span, learn to go beyond our comfort zone

Historicism: Few models, first to try what he’s doing, difficulty of being first, groping quality to efforts

Intellectual ambition or pretensions

Edgar Huntly's exploration of the unconscious (sleepwalking = exploring underground caves = where our minds go when we lose conscious control) anticipates 20th century Modernism

By learning to read the past as our present in development. learn to read our present as the future in development--how most writers are reproducing familiar formulas, but a few writers are trying something new that introduces or meets the future-in-development

Critical thinkers learn to think way out of box of present

Instructor's personal reasons for liking Edgar Huntly

This book's as crazy as I am!

And if you read it, now you are too.

(gothic as projection of unconscious mind trying to make sense of an irrational world)

thanks to

https://memegenerator.net/instance/65237926

In 1799, caves or wilderness became a metaphor or model for the mind

In the 2000s, computers are our metaphors.