|

|

Online Texts

for Craig White's

Literature Courses

|

|

|

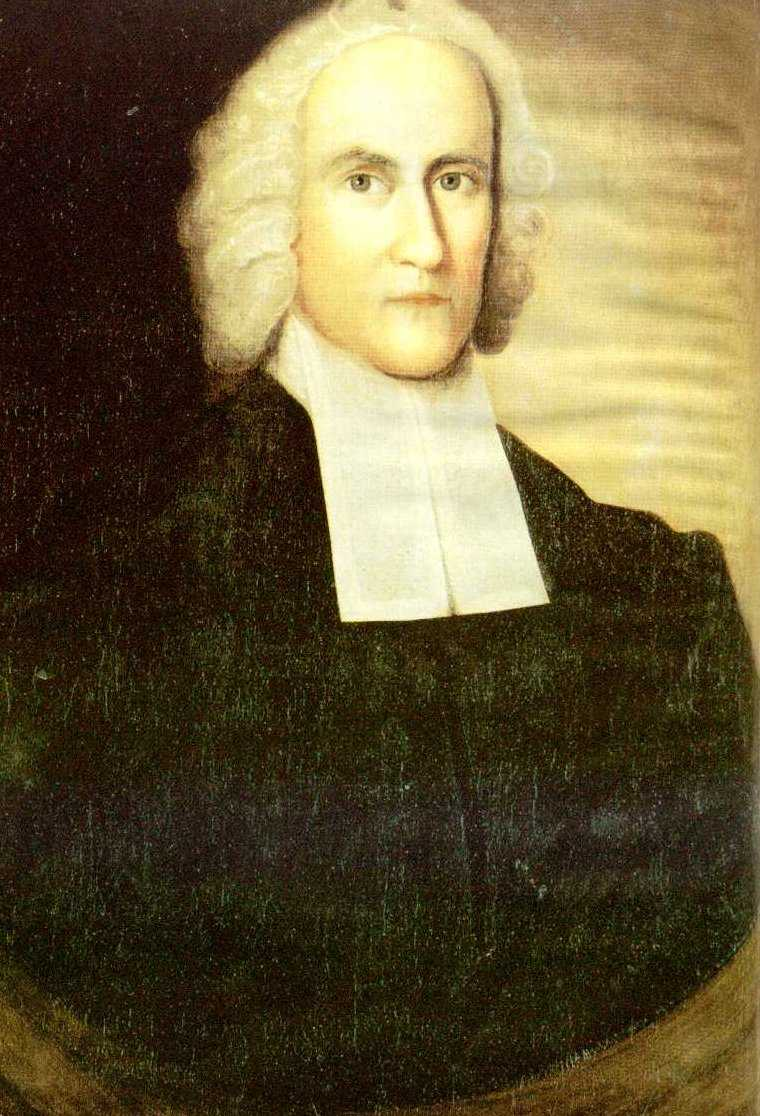

Jonathan Edwards (1703-58) Of Insects (excerpts) (1720; written when Edwards was 17) |

|

Instructor's note: This essay by a young Edwards is best-known today as the inspiration for a famous poem (see below) by the leading 20th-century poet Robert Lowell, but the essay also deepens our appreciation of Edwards's intellectual range in a time of change between the balance of science and religion. Today Edwards is best remembered for his sermon Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God and the religious emotionalism associated with the Great Awakening, in contrast to the Enlightenment attitudes of his contemporaries including the more secular-minded Founders of the USA like Benjamin Franklin. In contrast to this stereotype, "Of Insects" shows Edwards both aware of and practicing the science of the Enlightenment by his references to Sir Isaac Newton and by his careful powers of empirical observation. Yet Edwards retains a Puritanical overlay to his science by witnessing all actions of nature as evidences of the glory of God.

![]()

[1] Of all insects, no one is more wonderful than the

spider, especially with respect to their sagacity

[wisdom]

and admirable way of working. These spiders, for the present, shall be

distinguished into those that keep in houses and those that keep in

forests, upon trees, bushes, shrubs, etc. for I take ’em to be of very

different kinds and natures (there are also other sorts, some of which keep in

rotten logs, hollow trees, swamps and grass).

[2] Of these last [spiders in

forests], everyone knows the truth of their

marching in the air from tree to tree, and these sometimes at

five or six rods distance sometimes [rod =

5-6 yards]. Nor can anyone go out amongst

the trees in a dewy morning towards the latter end of August or the beginning of

September, but that he shall see hundreds of webs, made conspicuous by the dew

that is lodged upon them, reaching from one tree and shrub to another that

stands at a considerable distance, and they may be seen well enough by an

observing eye at noonday by their glistening against the sun.

[2a] And what is still more wonderful, I know I have several times seen, in a very calm and serene day at that time of year, standing behind some opaque body that shall just hide the disk of the sun and keep off his dazzling rays from my eye, multitudes of little shining webs and glistening strings of a great length, and at such a height as (that one would think they were tacked to the sky by one end, were it not that they were moving and floating. And there often appears at the end of these webs a spider floating and sailing in the air with them, which I have plainly discerned in those webs that were nearer to my eye.

[2b]

And once [I] saw a very large spider, to my surprise, swimming in

the air in this manner, and others have assured me that they often have seen

spiders fly. The appearance is truly very pretty and pleasing, and it

was so pleasing, as well as surprising, to me, that I resolved to

endeavor to satisfy my curiosity about it, by finding out the way and of their

doing it, being also persuaded that, if I could find out how they flew,

I could easily find out how they made webs from tree to tree.

[3] And accordingly, at a time when I was

in the woods, I happened to see one of these spiders on a bush. So I

went to the bush and shook it, hoping thereby to make him uneasy upon it and

provoke him to leave it by flying, and took good care that he should

not get off from it in any other way. So I continued constantly to shake it,

which made him several times let himself fall by his web a little. But he would

presently ‘creep up again, till at last he was pleased, however, to

leave that bush and march along in the air to the next, but which way I did not

know, nor could I conceive, but resolved to watch him more narrowly next time.

[3a] So I brought [him] back to the same bush again. To be sure that there

was nothing for him to go upon the next time, I whisked about a stick I had in

my hand on all sides of the bush, that I might break any web going from it, if

there were any, and leave nothing else for him to go on but the clear air, and

then shook the bush as before. But it was not long before he again to my

surprise went to the next bush. I took him off upon my stick and,

holding of him near my eye, shook the stick as I had done the bush, whereupon he

let himself down a little, hanging by his web, and [I] presently perceived a web

out from his tail and a good way into the air. I took hold of it with my hand

and broke it off, not knowing but that I might take it out to the stick with him

from the bush; but then I plainly perceived another such string to

proceed out at his tail.

[4] I now conceived I had found out the whole mystery. I

repeated the trial over and over again till I was fully satisfied of his way of

working, which I don’t only conjecture, to be on this wise, viz.: They,

when they would go from tree to tree, or would sail in the air, let themselves

hang down a little way by their web: and then put out a web at their tails,

which being so exceeding rare [thin,

rarefied] when it first comes from the spider as to

be lighter than the air, so as of itself it will ascend in it (which I know by

experience), the moving air takes it by the end, and by the spider’s

permission, pulls it out and bears it out his tail to any length, and if the

further end of it happens to catch by a tree or anything, why, there’s a web for

him to go over upon. And the spider immediately perceives it and feels when it

touches, much after the same manner as the soul in the brain immediately

perceives when any of those little nervous strings that proceed from it are in

the least jarred by external things. And this very way I have seen

spiders go from one thing to another, I believe fifty times at least since I

first discovered it. . . .

[5] There remain only two difficulties.

. . . [Speculations on the spiders and their creation of their webs follows.] .

. . But whether that be their way

or no I can’t say — but without scruple, that or a better, for we always

find things done by nature as well or better than [we] can imagine beforehand.

[6] Corollary [practical outcome]. We hence see the exuberant goodness of the Creator, who hath not only provided for all the necessities, but also for the pleasure and recreation of all sorts of creatures, and even the insects and those that are most despicable.

[7] Another thing particularly notable and worthy of being

inquired into about these webs is that they, which are so exceeding small and

fine as that they cannot be discerned except held in a particular position with

respect to the sun or against some dark place when held close to the eye, should

appear at such a prodigious height in the air when near betwixt us and the sun .

. . . But the chief reason must be

referred to that incurvation of the rays passing by the edge of any body, which

Sir Isaac Newton has proved.

[8] One thing more I shall take notice of, before I dismiss

this subject, concerning the end of nature in giving spiders this way of

flying, which though we have found in the corollary to be their pleasure and

recreation, yet we think a greater end is at last their destruction.

And what makes us think so is because that is necessarily and naturally brought

to pass by it, and we shall find nothing so brought to pass by nature but what

is the end of those means by which is brought to pass; and we shall further

evince it by and by, by strewing the great usefulness of it. But we must show

how their destruction is brought to pass by it.

[9] I say then, that

by this means almost all the spiders upon

the land must necessarily be swept first and last into the sea. For we have

observed already that they never fly except in fair weather. We

may now observe that it is never fair weather, neither in this country nor any

other, except when the wind blows from the midland parts, and so towards the

sea. . . . And as to other sorts

of flying insects, such as butterflies, millers, moths, etc., I remember

that, when I was a boy, I have at the same time of year lien

[lying]

on the ground upon my back and beheld abundance of them, all flying

southeast, which I then thought were going to a warm country. So that,

without any doubt, almost all manner of aerial insects, and also spiders which

live upon them and are made up of them, are at the end of the year swept and

wafted into the sea and buried in the ocean, and leave nothing behind

them but their eggs for a new stock the next year.

[10] Corollary 1.

[corollary =

deduction]

Hence also we may behold and admire at the wisdom of the Creator,

and be convinced that is exercised about such little things, in this

wonderful contrivance of annually carrying off and burying the corrupting

nauseousness of our air, of which flying insects are little collections, in the

bottom of the ocean where it will do no harm, and especially the

strange way of bringing this about in spiders (which are collections of these

collections, their food being flying insects) which want wings whereby it might

be done. And what great inconveniences should we labor under if there were no

such way. For spiders and flies are so exceeding multiplying creatures

that if they only slept or lay benumbed in [winter] and were raised again in the

spring, which is commonly supposed, it would not be many years before we should

be as much plagued with their vast numbers as Egypt was. And if they

died for good and all in winter they, by the renewed heat of the sun, would

presently again be dissipated into those nauseous vapors which they are made up

of, and so would be of no use or benefit in that [in] which now they are so very

serviceable.

[11] Corol.

[Corollary] 2. Admire also the Creator in so nicely and

mathematically adjusting their multiplying nature, that notwithstanding their

destruction by this means and the multitudes that are eaten by birds, that they

do not decrease and so, little by little, come to nothing; and in so adjusting

their destruction to their multiplication that they do neither increase, but

taking one year with another, there is always just an equal number of them.

[12] Another reason why they will

not fly at any other time but when a dry wind blows, is because a moist wind

moistens the web and makes it heavier than the air. And if they had the sense to

stops themselves, we should have hundreds of times more spiders and flies by the

seashore than anywhere else.

![]()

Robert Lowell (1917-77)

Mr. Edwards and the Spider

I saw the spiders marching through the

air,

Swimming from tree to tree

that mildewed day

In latter August

when the hay

Came creaking to the

barn. But where

The wind is

westerly,

Where gnarled November

makes the spiders fly

Into the

apparitions of the sky,

They

purpose nothing but their ease and die

Urgently beating east to sunrise and the sea;

What are we in the hands of the great

God?

It was in vain you set up

thorn and briar

In battle array

against the fire

And treason

crackling in your blood;

For the

wild thorns grow tame

And will do

nothing to oppose the flame;

Your

lacerations tell the losing game

You play against a sickness past your cure.

How will the hands be strong? How will the heart endure?

A very little thing, a little worm,

Or hourglass-blazoned spider, it is said,

Can kill a tiger. Will the dead

Hold up his mirror and affirm

To the four winds the smell

And flash of his authority? It's well

If God who holds you to the pit of hell,

Much as one holds a spider, will destroy,

Baffle and dissipate your soul. As a small boy

On Windsor Marsh, I saw the spider die

When thrown into the bowels of fierce fire:

There's no long struggle, no desire

To get up on its feet and fly

It stretches out its feet

And dies. This is the sinner's last retreat;

Yes, and no strength exerted on the heat

Then sinews the abolished will, when sick

And full of burning, it will whistle on a brick.

But who can plumb the sinking of that

soul?

Josiah Hawley, picture

yourself cast

[Jn Edwards's uncle, who committed suicide during

the Great Awakening]

Into a brick-kiln where the blast

Fans your quick vitals to a coal—

If measured by a glass,

How long would it seem burning! Let there pass

A minute, ten, ten trillion; but the blaze

Is infinite, eternal: this is death,

To die and know it. This is the Black Widow, death.

—