|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

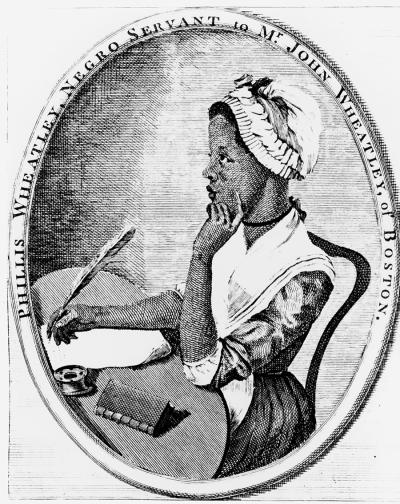

Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784) On Being Brought From Africa to America(1773) |

|

Instructor's notes: Phillis Wheatley, like Olaudah Equiano, was born in West Africa. In 1761 she was sold by a local chief to a European trader who brought her on the merchant ship The Phillis to Boston, where she was bought by the merchant John Wheatley to be a servant to his wife. (The New England states gradually abolished slavery in the late 1700s to early 1800s.)

The Wheatleys' children taught Phillis to read and write, and Mr. Wheatley, a progressive, provided her a classical education in Latin and Greek. In her teens Phillis began writing poetry imitative of classical poets like John Milton and Alexander Pope.

In 1773 she visited London with the Wheatleys, where publication of her first book, Poems on Various Subjects, was financed by the Countess of Huntingdon. In 1776 she met George Washington, for whom she had composed a poem of tribute.

In 1773 the Wheatleys emancipated Phillis. In the late 1770s she married John Peters, a free black grocer, but they suffered hardships of finance and health. She attempted to find sponsors for a second volume of poems, but it was never published. She died 5 December 1784 at age 31.

Wheatley High School in Houston's Fifth Ward, established 1927, is named for Phillis Wheatley. (See photo below.)

Discussion questions:

1. Since African slavery is, with American Indian land dispossession, one of the two "original sins" of the USA's dominant culture, the poem's attribution of enslavement to "mercy" can disturb modern readers—i.e., the Christian God's plan for universal salvation is responsible for the forced migration of African slaves to the New World? What are the possible tones in which this opening (and the entire poem) may be read?

1a. What are the possibilities of reading this question within the context in which Wheatley was writing?

1b. Is it possible to read the poem as an example of "double language," where the same words send different messages to different audiences?

2. Lines 2 and 5-8 refer to Western Civilization's "color code," in which light or white is associated with knowledge and goodness or purity, and dark or black with ignorance and evil or corruption. What challenges does the color code or skin color present to the poem's potential tone of hope and gratitude for slavery? How does the poem resolve these challenges or conflicts?

2a. What kind of metaphor is "refined?" What is its possible application to the color code or to religious salvation?

![]()

On Being Brought From Africa to America

[1]

'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

[Pagan = non-Christian, irreligious]

[2]

Taught my benighted soul to understand

[benighted = in intellectual or moral darkness]

[3]

That there's a God, that there's a Savior too:

[4]

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

[5]

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

[sable = black]

[6]

"Their color is a diabolic dye."

[diabolic = like or resembling the devil]

[7]

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

[Cain = first son of Adam & Eve, who slew his brother

Abel. Traditional European art depicted Cain as darker.]

[8]

May be refined and join the angelic train.

[train = company, body of attendants, here

angels in God's presence]

![]()

"If Wheatley

does not satisfy those who wonder at her seeming obliviousness to the condition

of the vast dark body, seven hundred thousand strong, held slaves in perpetuity,

perhaps it is because those commentators have failed to survey the poet’s life,

work, and society as complex, interrelated phenomena. The most just assessment

seems to be that Wheatley’s career ranks with the best that early America has to

offer."