Instructional Materials for

Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

Teaching Literature with Religion |

|

Problems with discussing religion in a

public school or university (or anywhere besides church or family)

Religion is so universal yet intimate that any conception or

part of it touches all kinds of personal-to-cosmic subjects—politics,

personal values, community relations, attitudes toward authority, ideas about

family

Like literature, most world religions start with a limited core of canonical or authoritative texts ("the classics," the Bible, the Koran) but constantly produces fresh words and meanings about them, creating power, tradition, and change through literacy.

Literature and religion resemble each other also through their dependence on symbols and narratives.

Beyond these neutral resemblances, discussions of literature

and religion are both productive and perilous. No matter what you say or how fairly or truly you speak about religion, there's always more to say. Any single

statement or description concerning any religious subject is inadequate and

therefore invite exceptions

More words!

Despite this shared sense that "we can never say it all" about religion or literature, even well-intentioned expressions may go wrong and cause hurt.

> common sense: “Never talk about religion or politics.”

True enough, but with a cost: we may avoid

discussing what gives meaning

If literature can't discuss significant subjects, then discussion of literature becomes limited to formal discussions, which are worthy but not why most people read.

If you solve the problem by discussing such subjects only with people who already agree

Literature may provide models of how to discuss such subjects in a society with free and diverse beliefs.

First

words of

Flip-side of disestablishment: you cannot disrespect other people's religion, just as they cannot disrespect yours.

Working compromise in public schools: School authorities cannot lead prayers or make religious appeals to mixed student body; schools must accommodate voluntary religious expression.

You can't teach a particular religion as the only truth, but you can discuss the nature of religion generally or of particular religions or their texts / scriptures.

Historical consequences of Religious Freedom:

Religion, instead of being promoted by the state, enters the free market of ideas, which compete with each other for popular support.

United States = secular government + religious people (with

implied converse: religious government = irreligious people)

If Americans hate government, associating religion with

government may make them hate religion

Resulting attitude for teachers and students?

Most "World Religions" (e.g., Christianity, Islam) require you to embrace their beliefs and reject the beliefs of other religions.

Public discussion of religion suspends endorsement or judgment in favor of empirical learning and critical thinking.

Study of religion or religious literature shifts to History of Ideas, History of

Religion, Intellectual history

Particular Points of Conflic

Evolution & Creationism

Controversy over Founders as “Godly Men” or Religious

Skeptics / Secularists

For “Secularists”: U.S. Constitution mentions religion only

twice, in First Amendment against establishment and earlier provision against

"religious tests" for office-holders. The only potentially offsetting provisions

are the Declaration's references to “Creator” & “Nature’s God”

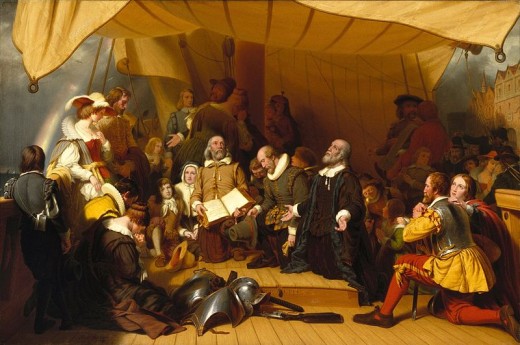

For “Godly Men”: private letters and comments, anecdotes,

popular art

More positively:

Religion as a way to make politics and history interesting

Study of religion resembles study of literature: both feature

human figures, narratives, symbols

Many good literature students have strong religious backgrounds and are thereby accustomed to discussing writing and using words to express meaning.

The "canon" of literary works is comparable to scripture as a collection of texts that a person should read.