|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

|

John Smith (1580-1631) from A General History of Virginia (1624) |

|

Instructor's note: Events occur in 1607-8 in English settlement of Jamestown, Virginia.

|

|

The encounter in the early 1600s between John Smith of the Jamestown Colony and Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Powhatan of the Powhatan Confederacy of American Indians remains one of the best-known and most dramatic episodes of colonial history. Over four centuries—and even from the start—events at Jamestown, particularly the relationship between Smith, Pocahontas, and her father Powhatan, have survived and occasionally flourished in the imaginations of later Americans.

General questions for the General History of Virginia:

![]() What kinds of

literary pleasures

(or pains) do the selections offer, either in surface style or plot?

What kinds of

literary pleasures

(or pains) do the selections offer, either in surface style or plot?

![]() How is John Smith a

prototypical

American hero? For gender and ethnic studies, what role do Pocahontas and

her father Powhatan play in relation to this hero?

How is John Smith a

prototypical

American hero? For gender and ethnic studies, what role do Pocahontas and

her father Powhatan play in relation to this hero?

Literary & historical interests or pleasures to the General History of Virginia:

Smith's capture and release by Powhatan and Pocahontas constitute an early captivity narrative.

The realistic facts and details of Smith's account qualify its genre as "history," but Smith popularizes the story by telling it in the genre of male-romance or adventure, with possible undertones of woman's romance or a love story via his relation with Pocahontas.

Romance elements:

![]() Smith's

heroic individualism; as in a classic knightly

romance or a later Western, Smith as hero saves himself and others, and is himself saved by Pocahontas's

intervention.

Smith's

heroic individualism; as in a classic knightly

romance or a later Western, Smith as hero saves himself and others, and is himself saved by Pocahontas's

intervention.

![]() Smith's

references to Pocahontas's "love" may suggest a

love-romance, but in fact Smith was almost 30 while Pocahontas was about 12

or 13 at the time of their adventure. Pocahontas and John Smith briefly

maintained diplomatic communications between their two peoples, but no

further relationship ever developed, and Pocahontas later married another young

adolescent.

Smith's

references to Pocahontas's "love" may suggest a

love-romance, but in fact Smith was almost 30 while Pocahontas was about 12

or 13 at the time of their adventure. Pocahontas and John Smith briefly

maintained diplomatic communications between their two peoples, but no

further relationship ever developed, and Pocahontas later married another young

adolescent.

![]() Later versions of the story such as Disney's animated film

Pocahontas increase the romance-factor by making Smith and

Pocahontas the same age.

Later versions of the story such as Disney's animated film

Pocahontas increase the romance-factor by making Smith and

Pocahontas the same age.

|

Do realistic facts and details spoil the Romance?

Question: If later generations of Americans read the Smith-Pocahontas story as a romance, what purposes does that interpretation serve for America's dominant culture? |

1850s rendering of John Rolfe (1585-1622) & Pocahontas |

Historical interests:

Smith's freewheeling, anti-authoritarian, individualistic attitude and behavior are far more typical of the "Cavaliers" who settled "Virginia" or the southern parts of the future USA than of the Puritans who settled "New England" as one of early European-America's only communitarian colonies.

Challenges to reading Smith's General History:

![]() Spelling

is

modernized from Smith's original, but otherwise his language broadly

resembles that of his

contemporary William Shakespeare. Readers in an English-language classroom

are expected to manage centuries of changes in language, in contrast to the

comparative ease of reading modern translations of Spanish-language writers

like Columbus or Cabeza de Vaca.

Spelling

is

modernized from Smith's original, but otherwise his language broadly

resembles that of his

contemporary William Shakespeare. Readers in an English-language classroom

are expected to manage centuries of changes in language, in contrast to the

comparative ease of reading modern translations of Spanish-language writers

like Columbus or Cabeza de Vaca.

![]() Smith refers to himself as "he"

rather than as "I." Why? What effect on reader or on perceptions of Smith's

ego?

Smith refers to himself as "he"

rather than as "I." Why? What effect on reader or on perceptions of Smith's

ego?

![]() The original

genre of

Smith's General History was something like a business report

designed to defend his actions on earlier explorations and to raise money

for further explorations.

The original

genre of

Smith's General History was something like a business report

designed to defend his actions on earlier explorations and to raise money

for further explorations.

artist's sketch of Fort James

![]()

|

from A General History of Virginia "Virginia" = early southern English coloniesin North America |

from Chapter II. What Happened Till the First Supply

[para. 1] Being thus left to our fortunes, it fortuned that within ten days scarce ten amongst us could either go or well stand, such extreme weakness and sickness oppressed us. . . . But our President . . . engross[ed] to his private [use] oatmeal, sack, oil, aquavitae, beef, eggs, or what not, but the [common] kettle. That, indeed, he allowed equally to be distributed, and that was half a pint of wheat, and as much barley boiled with water for a man a day. . . . Our drink was water, our lodgings castles in the air. With this lodging and diet, our extreme toil in bearing and planting Pallisadoes [palisades, fortifications] so strained and bruised us, and our continual labor in the extremity of the heat had so weakened us, as were cause sufficient to have made us as miserable in our native country or any other place in the world.

[para. 2] From May to September those that escaped lived upon sturgeon [bony fish] and sea crabs. Fifty in this time we buried. The rest seeing the President's projects to escape these miseries in our pinnace [small sailing ship] by flight (who all this time had neither felt want nor sickness) so moved our dead spirits that we deposed him and established Ratcliffe in his place. . . l. But now was all our provision spent, the sturgeon gone, all helps abandoned. Each hour expecting the fury of the savages, when God, the patron of all good endeavors, in that desperate extremity so changed the hearts of the savages, that they brought such plenty of their fruits and provisions that no man wanted. [As in Mary Rowlandson's captivity narrative, Smith attributes Indian hospitality to the English or Christian God]

[para. 3] . . . Such actions have ever since the world's beginning been subject to such accidents, and everything of worth is found full of difficulties; but nothing so difficult as to establish a commonwealth so far remote from men and means, and where men's minds are so untoward as neither do well themselves nor suffer others. But to proceed.

[para. 4] The new President and Martin, being little beloved, of weak judgment in dangers and less industry in peace, committed the managing of all things abroad to Captain Smith; who by his own example, good words, and fair promises set some to mow, others to bind thatch, some to build houses, others to thatch them, himself always bearing the greatest task for his own share, so that in short time he provided most of them lodgings, neglecting any for himself. [heroic individualism typical of romance]

[para. 5] This done, seeing the savages' superfluity [food the Indians gifted] begin to decrease (with some of the workmen) shipped himself in the shallop to search the country for trade. The want of the language, knowledge to manage his boat without sails, the want of a sufficient power (knowing the multitude of the savages), apparel for his men, and other necessaries, were infinite impediments, yet no discouragement. [<realistic limits but Romantic resolve] Being but six or seven in company, he went down the river to Kecoughtan, where at first they [Indians] scorned him, as a famished man, and would in derision offer him a handful of corn, a piece of bread for their swords and muskets, and such like proportions also for their apparel.

[para. 6] But seeing by trade and courtesy there was nothing to be had, he made bold to try such conclusions as necessity enforced, though contrary to his commission. [He] let fly his muskets, ran his boat on shore, whereat they all fled into the woods. So marching towards their houses, they might see great heaps of corn: much ado he had to restrain his hungry soldiers from present [immediate] taking of it, expecting as it happened that the savages would assault them; as not long after they did with a most hideous noise. Sixty or seventy of them, some black, some red, some white, some parti-colored came in a square order, singing and dancing out of the woods, with their Okee (which was an idol made of skins, stuffed with moss, all painted and hung with chains and copper) borne before them. And in this manner, being well armed with clubs, targets, bows and arrows, they charged the English, that so kindly received them with their muskets loaden with pistol shot, that down fell their god and divers lay on the ground. The rest fled again to the woods and ere long sent one of the Quiyoughkasoucks to offer peace and redeem their Okee. Smith told them if only six of them would come unarmed and load his boat, he would not only be their friend, but restore them their Okee, and give them beads, copper, and hatchets besides: which on both sides was to their contents performed: and then they brought him venison, turkeys, wild fowl, bread, and what they had, singing and dancing in sign of friendship till they departed. . . .

[para. 7] And now [1608], the winter approaching, the rivers became so covered with swans, geese, ducks, and cranes, that we daily feasted with good bread, Virginia peas, pumpkins, and putchamins [persimmons], fish, fowl, and divers sorts of wild beasts as fat as we could eat them: so that none of our tuftaffety humorists desired to go for England. [natural abundance of America as Romantic materialist or sensory appeal]

[para. 8] But our comedies never endured long without a tragedy; some idle exceptions being muttered against Captain Smith for not discovering the head of Chickahamania River, and taxed by the Council to be too slow in so worthy an attempt. The next voyage he proceeded so far that with much labor by cutting of trees asunder he made his passage; but when his barge could pass no farther, he left her in a broad bay out of danger of shot, commanding none should go ashore till his return: himself with two English and two savages went up higher in a canoe; but he was not long absent but his men went ashore, whose want of government [lack of discipline] gave both occasion and. opportunity to the savages to surprise one George Cassen, whom they slew, and much failed not to have cut off the boat and all the rest.

[para. 9] Smith, little dreaming of that accident, being got to the marshes at the river's head, twenty miles in the desert, had his two men slain, as is supposed, sleeping by the canoe, whilst himself by fowling [shooting for birds] sought them victual [food]: finding he was beset with 200 savages, two of them he slew, still defending himself with the aid of a savage his guide, whom he bound to his arm with his garters, and used him as a buckler [shield], yet he was shot in his thigh a little, and had many arrows that stuck in his clothes; but no great hurt, till at last they took him prisoner. [<Rambo-worthy male-Romance adventure] When this news came to Jamestown, much was their sorrow for his loss, few expecting what ensued.

[para. 10] Six or seven weeks those barbarians kept him prisoner [captivity narrative], many strange triumphs and conjurations they made of him, yet he so demeaned himself amongst them, as he not only diverted them from surprising the fort but procured his own liberty, and got himself and his company such estimation amongst them that those savages admired him more than their own Quiyouckosucks [gods].

[para. 11] The manner how they used and delivered him is as follows. . . .

| [para. 12] He demanding for their captain, they showed him Opechankanough, king of Pamaunkee, to whom he gave a round ivory double compass dial [illustration >]. Much they marveled at the playing of the fly and needle, which they could see so plainly and yet not touch it because of the glass that covered them. [<techno-shock] But when he demonstrated by that globe-like jewel [compass] the roundness of the earth and skies, the sphere of the sun, moon, and stars, and how the sun did chase the night round about the world continually [Smith knows the earth is round but thinks the sun goes around it]; the greatness of the land and sea, the diversity of nations, variety of complexions, and how we were to them antipodes, and many other such like matters, they all stood as amazed with admiration. Notwithstanding [regardless], within an hour after they tied him to a tree, and as many as could stand about him prepared to shoot him: but the king holding up the compass in his hand, they all laid down their bows and arrows, and in a triumphant manner led him to Orapaks, where he was after their manner kindly feasted, and well used. |

compass (navigational) |

|

[para. 13] At last they brought him to Werowocomoco, where was Powhatan, their emperor. Here more than two hundred of those grim courtiers stood wondering at him, as he had been a monster [reverse gothic?]; till Powhatan and his train had put themselves in their greatest braveries. Before a fire upon a seat like a bedstead, he [Powhatan] sat covered with a great robe, made of raccoon skins, and all the tails hanging by [realistic detail]. On either hand did sit a young wench of sixteen or eighteen years, and along on each side the house, two rows of men, and behind them as many women, with all their heads and shoulders painted red, many of their heads bedecked with the white down of birds, but every one with something, and a great chain of white beads about their necks. At his entrance before the king, all the people gave a great shout. The queen of Appamatuck was appointed to bring him water to wash his hands, and another brought him a bunch of feathers, instead of a towel to dry them. [realistic detail, reality effect] [para. 14] Having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on him [Smith], dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs to beat out his brains, Pocahontas, the king's dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death: whereat the emperor was contented he [Smith] should live to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper; for they thought him as well [as capable] of all occupations as themselves. For the king himself will make his own robes, shoes, bows, arrows, pots; plant, hunt, or do anything so well as the rest. [Smith marvels at premodern society, in which each person can perform all appropriate tasks, in contrast to modern society's specialization or distribution of labor] |

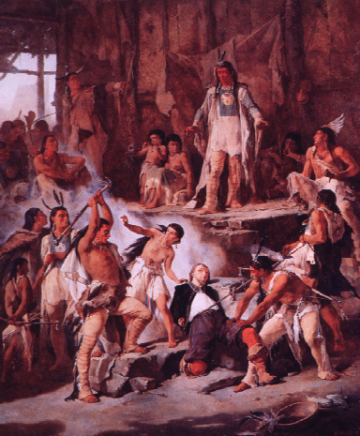

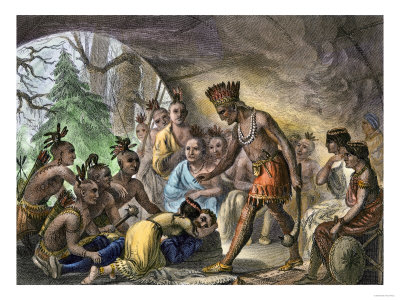

[artist's rendition of Pocahontas's rescue of Smith;

|

[para. 15] [note gothic potential in this paragraph>] Two days after [later], Powhatan having disguised himself in the most fearfulest manner he could, caused Captain Smith to be brought forth to a great house in the woods, and there upon a mat by the fire to be left alone. Not long after, from behind a mat that divided the house was made the most dolefulest noise he ever heard; then Powhatan, more like a devil than a man, with some two hundred more as black as himself, came unto him and told him now they were friends, and presently he should go to Jamestown, to send him two great guns, and a grindstone, for which he would give him the county of Capahowosick, and for ever esteem him as his son Nantaquoud. [Pocahontas is later converted, but Smith has been adopted in manner of many Indians with captives, esp. young people and men, e.g. Daniel Boone, Sam Houston]

[para. 16]

So to

[para. 17]

Now in

[para. 18] Some no better than they should be, had plotted with the President, the next day to have put him [Smith] to death by the Levitical law [strict Biblical law?], for the lives of Robinson and Emry [Englishmen ambushed by Indians], pretending the fault was his [Smith's] that had led them [Robinson & Emry] to their ends: but he quickly took such order with such lawyers that he laid them by the heels till he sent some of them prisoners for England.

[para. 19] Now every once in four or five days, Pocahontas, with her attendants, brought him so much provision that saved many of their lives that else for all this had starved with hunger.

[para. 20] His relation of the plenty he had seen, especially at Werawocomoco, and of the state and bounty of Powhatan (which till that time was unknown), so revived their dead spirits (especially the love of Pocahontas) as all men's fear was abandoned. ["love" here likely means care, concern, or charity--that is, the men are "revived" to learn that Pocahontas will help provide them with food]

[para. 21] Thus you may see what difficulties still crossed any good endeavor; and the good success of the business being thus oft brought to the very period of destruction; yet you see by what strange means God hath delivered it.

![]()

Additional images of Pocahontas, Powhatan, & John Smith

|

|

|

1616 English portrait & engraving of Pocahontas; real name Matoaka inscribed on right

|

|

|

later artists' conceptions of Pocahontas's rescue of John Smith

![]()

|

|

|

Disney's Pocahontas (1995)

![]()

[para. 22]

Their

simplicity.

Most things they saw with us

[such] as Mathematical

Instruments, Sea Compasses; the virtue of the Loadstone [magnet, compass], Perspective Glasses

[telescopes], burning Glasses [magnifying

glasses]: Clocks to go of themselves; Books, writing, Guns,

and such like; so far exceeded their capacities, that they thought they were

rather the works of gods [rather] than men; or at least the gods had taught vs

how to make them, which loved us so much better then them; & caused many of them

give credit to what we spake concerning our God. In all places where I came, I did my best to

make his immortal glory known. And I told them, although the Bible I showed

them, contained all; yet of itself, it was not of any such vertue [power] as I thought

they did conceive. Notwithstanding many would be glad to touch it, to kiss, and

embrace it, to hold it to their breasts, and heads, and stroke all their body

over with it.

[para. 23]

Their

strange opinions.

This

marvelous Accident in all the Country wrought so strange opinions of us, that

they could not tell whether to think us gods or men. And the rather

that all the space of their sickness, there was no man of ours knowne to

die, or much sick. They noted also we had no women, nor cared for any of theirs:

some therefore thought we were not born of women, and therefore not mortal, but

that we were men of an old generation many years past, & risen again from

immortality. Some would prophesy there were more of

our generation yet to come, to kill theirs and take their places. Those that

were to come after us they imagined to be in the ayre, yet invisible and without

bodies: and that they by our entreaties, for love of us, did make the people die

as they did, by shooting invisible bullets into them.

[para. 24]

To

confirm this, their Physicians

[shamans or medicine men]

to excuse their Ignorance in curing the disease,

would make the simple people believe, that the strings of blood they sucked out

of the sick bodies, were the strings wherein the invisible bullets were tied,

and cast. Some thought we shot them our selves from the place where we dwelt,

and killed the people that had offended us, as we lifted, how far distant

soever. And others said it was the speciall work of God for our sakes, as we

had cause in some sort to thinke no less, whatsoever some doe, or may imagine

to the contrary; especially some

Astrologers

by the eclipse of the Sun we saw that year before our Voyage, and by a

Comet

which began to appear but a few days before the sicknesse began: but to

exclude them from being the special causes of so special an Accident, there

are farther reasons then I think fit to present or alledge. These their

opinions I have set down, that you may see there is hope to embrace the truth,

and honor, obey, fear and love us, by good dealing and government: though some

of our company towards the latter end, before we came away with Sir

Francis

Drake showed themselves too

furious, in slaying some of the people in some Towns, upon causes that on our

part might have bin born with more mildness; notwithstanding they justly had

deserved it. The best nevertheless in this, as in all actions besides, is to be

endeavored and hoped; and of the worst that may happen, notice to be taken with

consideration; and as much as may be eschewed; the better to allure them

hereafter to Civility and Christianity.

![]()

[You may stop reading here; passages below to be edited]

![]()

Chapter VII. The Presidency surrendred to Captaine Smith: the Arrivall and returne of the second Supply. And what happened.Capt. Smith goeth with 4. to Powhatan, when Newport feared with 120.A Virginia Maske.

In a fayre plaine field they made a fire, before which, he sitting upon a mat, suddainly amongst the woods was heard such a hydeous noise and shreeking, that the English betooke themselves to their armes, and seized on two or three old men by them, supposing Powhatan with all his power was come to surprise them. But presently Pocahontas came, willing him to kill her if any hurt were intended, and the beholders, which were men, women, and children, satisfied the Captaine there was no such matter. Then presently they were presented with this anticke;

thirtie young women came naked out of the woods, onely covered behind and before with a few greene leaves, their bodies all painted, some of one colour, some of another, but all differing, their leader had a fayre payre of Bucks hornes on her head, and an Otters skinne at her girdle, and another at her arme, a quiver of arrowes at her backe, a bow and arrowes in her hand; the next had in her hand a sword, another a club, another a pot-sticke; all horned alike: the rest every one with their severall devises. These fiends with most hellish shouts and cryes, rushing from among the trees, cast themselves in a ring about the fire, singing and dauncing with most excellent ill varietie, oft falling into their infernall passions, and solemnly againe to sing and daunce; having spent neare an houre in this Mascarado, as they entred in like manner they departed.

The Womens entertainement.Having reaccommodated themselves, they solemnly invited him to their lodgings, where he was no sooner within the house, but all these Nymphes more tormented him then ever, with crowding, pressing, and hanging about him, most tediously crying, Love you not me? love you not me? This salutation ended, the feast was set, consisting of all the Salvage dainties they could devise: some attending, others singing and dauncing about them; which mirth being ended, with fire-brands in stead of Torches they conducted him to his lodging.

Chap. VIII. Captaine Smiths Journey to Pamaunkee.

Captaine Smith, you may understand that I having seene the death of all my people thrice, and not any one living of these three generations but my selfe; I know the difference of Peace and Warre better then any in my Country. But now I am old and ere long must die, my brethren, namely Opitchapam, Opechancanough, and Kekataugh, my two sisters, and their two daughters, are distinctly each others successors. I wish their experience no lesse then mine, and your love to them no lesse then mine to you. But this bruit from Nandsamund, that you are come to destroy my Country, so much affrighteth all my people as they dare not visit you. What will it availe you to take that by force you may quickly have by love, or to destroy them that provide you food. What can you get by warre, when we can hide our provisions and fly to the woods? whereby you must famish by wronging us your friends. And why are you thus jealous of our loves seeing us unarmed, and both doe, and are willing still to feede you, with that you cannot get but by our labours? Thinke you I am so simple, not to know it is better to eate good meate, lye well, and sleepe quietly with my women and children, laugh and be merry with you, have copper, hatchets, or what I want being your friend: then be forced to flie from all, to lie cold in the woods, feede upon Acornes, rootes, and such trash, and be so hunted by you, that I can neither rest, eate, nor sleepe; but my tyred men must watch, and if a twig but breake, every one cryeth there commeth Captaine Smith: then must I fly I know not whether: and thus with miserable feare, end my miserable life, leaving my pleasures to such youths as you, which through your rash unadvisednesse may quickly as miserably end, for want of that, you never know where to finde. Let this therefore assure you of our loves, and every yeare our friendly trade shall furnish you with Corne; and now also, if you would come in friendly manner to see us, and not thus with your guns and swords as to invade your foes. To this subtill discourse, the President thus replyed.

Capt. Smiths Reply.Seeing you will not rightly conceive of our words, we strive to make you know our thoughts by our deeds; the vow I made you of my love, both my selfe and my men have kept. As for your promise I find it every day violated by some of your subjects: yet we finding your love and kindnesse, our custome is so far from being ungratefull, that for your sake onely, we have curbed our thirsting desire of revenge; els had they knowne as well the crueltie we use to our enemies, as our true love and courtesie to our friends. And I thinke your judgement sufficient to conceive, as well by the adventures we have undertaken, as by the advantage we have (by our Armes) of yours: that had we intended you any hurt, long ere this we could have effected it. Your people comming to James Towne are entertained with their Bowes and Arrowes without any exceptions; we esteeming it with you as it is with us, to weare our armes as our apparell. As for the danger of our enemies, in such warres consist our chiefest pleasure: for your riches we have no use: as for the hiding your provision, or by your flying to the woods, we shall not so unadvisedly starve as you conclude, your friendly care in that behalfe is needlesse, for we have a rule to finde beyond your knowledge.

Many other discourses they had, till at last they began to trade. But the King seeing his will would not be admitted as a law, our guard dispersed, nor our men disarmed, he (sighing) breathed his minde once more in this manner.

Powhatans importunity to have us unarmed to betray us.

Captaine Smith, I never use any Werowance so kindely as your selfe, yet from you I receive the least kindnesse of any. Captaine Newport gave me swords, copper, cloathes, a bed, towels, or what I desired; ever taking what I offered him, and would send away his gunnes when I intreated him: none doth deny to lye at my feet, or refuse to doe what I desire, but onely you; of whom I can have nothing but what you regard not, and yet you will have whatsoever you demand. Captaine Newport you call father, and so you call me; but I see for all us both you will doe what you list, and we must both seeke to content you. But if you intend so friendly as you say, send hence your armes, that I may beleeve you; for you see the love I beare you, doth cause me thus nakedly to forget my selfe.

Smith seeing this Salvage but trifle the time to cut his throat, procured the salvages to breake the ice, that his Boate might come to fetch his corne and him: and gave order for more men to come on shore, to surprise the King, with whom also he but trifled the time till his men were landed: and to keepe him from suspicion, entertained the time with this reply.

Cap. Smiths discourse to delay time, till he found oportunity to surprise the King.[III. 77.]Powhatan you must know, as I have but one God, I honour but one King; and I live not here as your subject, but as your friend to pleasure you with what I can. By the gifts you bestow on me, you gaine more then by trade: yet would you visit mee as I doe you, you should know it is not our custome, to sell our curtesies as a vendible commodity. Bring all your countrey with you for your guard, I will not dislike it as being over jealous. But to content you, to morrow I will leave my Armes, and trust to your promise. I call you father indeed, and as a father you shall see I will love you: but the small care you have of such a childe caused my men perswade me to looke to my selfe.

Powhatans plot to have murdered Smith.By this time Powhatan having knowledge his men were ready whilest the ice was a breaking, with his luggage women and children, fled. Yet to avoyd

suspicion, left two or three of the women talking with the Captaine, whilest hee secretly ran away, and his men that secretly beset the house. Which being presently discovered to Captaine Smith, with his pistoll, sword, and target hee made such a passage among these naked Divels; that at his first shoot, they next him tumbled one over another, and the rest quickly fled some one way some another: so that without any hurt, onely accompanied with John Russell, hee obtained the corps du guard. When they perceived him so well escaped, and with his eighteene men (for he had no more with him a shore) to the uttermost of their skill they sought excuses to dissemble the matter: and Powhatan to excuse his flight and the sudden comming of this multitude, sent our Captaine a great bracelet and a chaine of pearle, by an ancient Oratour that bespoke us to this purpose, perceiving even then from our Pinnace, a Barge and men departing and comming unto us.

A chaine of pearle sent the Captaine for a present.Captaine Smith, our Werowance is fled, fearing your gunnes, and knowing when the ice was broken there would come more men, sent these numbers but to guard his corne from stealing, that might happen without your knowledge: now though some bee hurt by your misprision, yet Powhatan is your friend and so will for ever continue. Now since the ice is open, he would have you send away your corne, and if you would have his company, send away also your gunnes, which so affrighteth his people, that they dare not come to you as hee promised they should.

Pretending to kill our men loaded with baskets, we caused them do it themselves.Then having provided baskets for our men to carry our

corne to the boats, they kindly offered their service to guard our Armes, that

none should steale them. A great many they were of goodly well proportioned

fellowes, as grim as Divels; yet the very sight of cocking our matches, and

being to let fly, a few wordes caused them to leave their bowes and arrowes to

our guard, and beare downe our corne on their backes; wee needed not importune

them to make dispatch. But our Bargesbeing left on the oase by the ebbe, caused

us stay till the next high-water, so that wee returned againe to our old

quarter. Powhatan and his Dutch-men brusting with desire to have the head of

Captaine Smith, for if they could but kill him, they thought all was theirs,

neglected not any oportunity to effect his purpose. The Indians with all the

merry sports they could devise, spent the time till night: then they all

returned to Powhatan, who all this time was making ready his forces to surprise

the house and him at supper. Notwithstanding the eternall all-seeing God did

prevent him, and by a strange meanes. For Pocahontas his dearest jewell and

daughter, in that darke night came through the irksome woods, and told our

Captaine great cheare should be sent us by and by: but Powhatan and all the

power he could make, would after come kill us all, if they that brought it could

not kill us with our owne weapons when we were at supper. Therefore if we would

live shee wished us presently to bee gone. Such things as shee delighted in, he

would have given her: but with the teares running downe her cheekes, shee said

shee durst not be seene to have any: for if Powhatan should know it, she were

but dead, and so shee ranne away by her selfe as she came. Within lesse then an

hour came eight or ten lusty fellowes, with graat platters of venison and other

victuall, very importunate to have us put out our matches (whose smoake made

them sicke) and sit down to our victuall. But the Captaine made them taste every

dish, which done hee sent some of them backe to Powhatan, to bid him make haste

for hee was prepared for his comming. As for them hee knew they came to betray

him at his supper: but hee would prevent them and all their other intended

villanies: so that they might be gone. Not long after came more messengers, to

see what newes; not long after them others. Thus wee spent the night as

vigilantly as they, till it was high-water, yet seemed to the salvages as

friendly as they to us: and that wee were so desirous to give Powhatan content,

as hee requested, wee did leave him Edward Brynton to kill him foule, and the

Dutchmen to finish his house; thinking at our returne from Pamaunkee the frost

would be gone, and then we might finde a better oportunity if necessity did

occasion it, little dreaming yet of the Dutch-mens treachery

Chapter II

What Happened Till the First Supply

Being thus left to our fortunes, it fortuned that within ten days scarce ten amongst us could either go or well stand, such extreme weakness and sickness oppressed us. And thereat none need marvel, if they consider the cause and reason, which was this: Whilst the ships stayed, our allowance was somewhat bettered by a daily proportion of biscuit, which the sailors would pilfer to sell, give, or exchange with us for money, sassafras, furs, or love. But when they departed, there remained neither tavern, beer house, nor place of relief but the common kettle. Had we been as free from all sins as gluttony and drunkenness, we might have been canonized for saints. But our President would never have been admitted, for engrossing to his private [use] oatmeal, sack, oil, aquavitae, beef, eggs, or what not, but the [common] kettle. That, indeed, he allowed equally to be distributed, and that was half a pint of wheat, and as much barley boiled with water for a man a day. And this having fried some 26 weeks in the ship's hold contained as many worms as grains, so that we might truly call it rather so much bran than corn. Our drink was water, our lodgings castles in the air. With this lodging and diet, our extreme toil in bearing and planting Pallisadoes so strained and bruised us, and our continual labor in the extremity of the heat had so weakened us, as were cause sufficient to have made us as miserable in our native country or any other place in the world. From May to September those that escaped lived upon sturgeon and sea crabs. Fifty in this time we buried. The rest seeing the President's projects to escape these miseries in our pinnace by flight (who all this time had neither felt want nor sickness) so moved our dead spirits that we deposed him and established Ratcliffe in his place (Gosnold being dead), Kendall deposed. Smith newly recovered [from illness], Martin and Ratcliffe was by his care preserved and relieved, and the most of the soldiers recovered with the skillful diligence of Master Thomas Wotton, our surgeon general. But now was all our provision spent, the sturgeon gone, all helps abandoned. Each hour expecting the fury of the savages, when God, the patron of all good endeavors, in that desperate extremity so changed the hearts of the savages, that they brought such plenty of their fruits and provisions that no man wanted.

And now, where some, affirmed it was ill done of the Council to send forth men so badly provided, this incontradictable reason will show them plainly they are too ill advised to nourish such ill conceits. First, the fault of our going was our own. What could be thought fitting or necessary we had; but what we should find or want or where we should be we were all ignorant; and supposing to make our passage in two months with victual to live and the advantage of the spring to work, we were at sea five months, where we both spent our victual and lost the opportunity of the time and season to plant by the unskillful presumption of our ignorant transporters that understood not at all what they undertook.

Such actions have ever since the world's beginning been subject to such accidents, and everything of worth is found full of difficulties; but nothing so difficult as to establish a commonwealth so far remote from men and means, and where men's minds are so untoward as neither do well themselves nor suffer others. But to proceed.

The new President and Martin, being little beloved, of weak judgment in dangers and less industry in peace, committed the managing of all things abroad to Captain Smith; who by his own example, good words, and fair promises set some to mow, others to bind thatch, some to build houses, others to thatch them, himself always bearing the greatest task for his own share, so that in short time he provided most of them lodgings, neglecting any for himself.

This done, seeing the savages' superfluity begin to decrease (with some of the workmen) shipped himself in the shallop to search the country for trade. The want of the language, knowledge to manage his boat without sails, the want of a sufficient power (knowing the multitude of the savages), apparel for his men, and other necessaries, were infinite impediments, yet no discouragement. Being but six or seven in company, he went down the river to Kecoughtan, where at first they scorned him, as a famished man, and would in derision offer him a handful of corn, a piece of bread for their swords and muskets, and such like proportions also for their apparel. But seeing by trade and courtesy there was nothing to be had, he made bold to try such conclusions as necessity enforced, though contrary to his commission. [He] let fly his muskets, ran his boat on shore, whereat they all fled into the woods. So marching towards their houses, they might see great heaps of corn: much ado he had to restrain his hungry soldiers from present taking of it, expecting as it happened that the savages would assault them; as not long after they did with a most hideous noise. Sixty or seventy of them, some black, some red, some white, some parti-colored came in a square order, singing and dancing out of the woods, with their Okee (which was an idol made of skins, stuffed with moss, all painted and hung with chains and copper) borne before them. And in this manner, being well armed with clubs, targets, bows and arrows, they charged the English, that so kindly received them with their muskets loaden with pistol shot, that down fell their god and divers lay on the ground. The rest fled again to the woods and ere long sent one of the Quiyoughkasoucks to offer peace and redeem their Okee. Smith told them if only six of them would come unarmed and load his boat, he would not only be their friend, but restore them their Okee, and give them beads, copper, and hatchets besides: which on both sides was to their contents performed: and then they brought him venison, turkeys, wild fowl, bread, and what they had, singing and dancing in sign of friendship till they departed. . . .