popular meaning of "romance"; love stories usually follow the disruption > trials > transcendence pattern of the romance narrative |

Romance . . .

as narrative, plot,

or story (i.e., "not just a love story," though it might be) (see also Romanticism; genres; narrative genres; melodrama)

|

even sweaty-guy hero-stories follow the romance narrative |

Structure of romance narrative

situation, relationships apparently normal > outside force disrupts > hero begins quest to resolve or restore > tests / trials > achievement of goal / transcendence

![]()

![]()

![]()

In popular use today, "romance" means love or a love story . . .

but in literary studies romance means a broader, more inclusive type of story or narrative that usually features a hero's or heroine's journey or quest through tests and trials (often involving a villain or antagonist) in order to reach a transcendent goal, whether love, salvation or rescue, or justice (usually revenge).

The narratives or story-lines of most popular movies and novels can be characterized as romances. A familiar variant or combination in film is "romantic comedy" (Sleepless in Seattle, When Harry Met Sally, etc) which typically involves a journey or plot in which two charming but mismatched characters endure mistakes and obstructions to arrive at a common union and save each other through love (which ends the story).

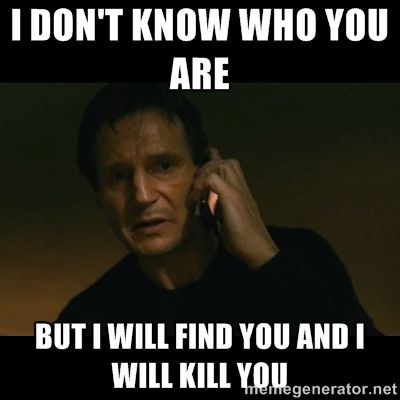

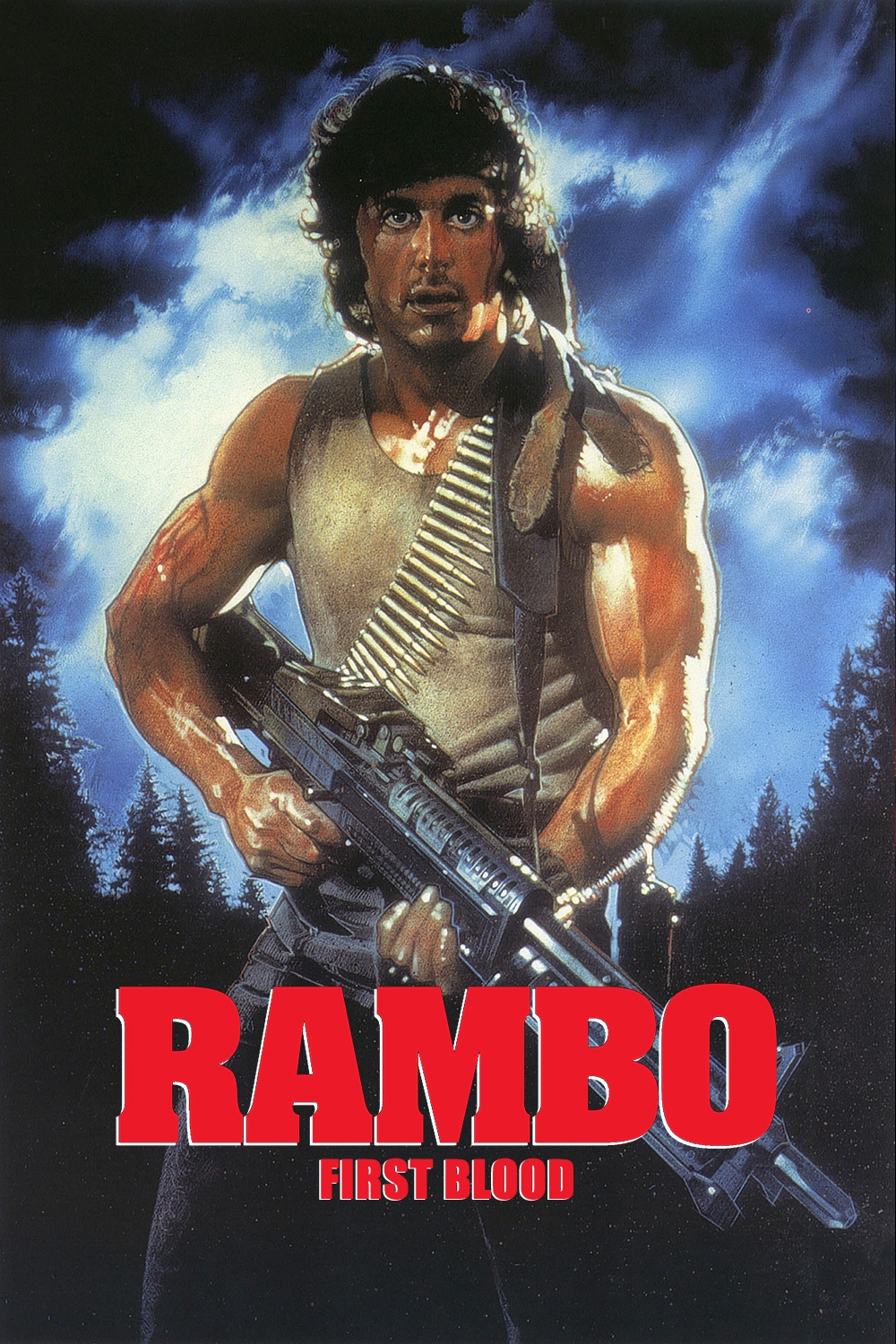

But macho action-adventure movies like Rocky, Rambo, Taken, and The Transporter are also romances, often involving a quest for vengeance for the death of a loved one, or the rescue of a loved one. A love-element may be present but is often de-emphasized for the sake of the larger narrative quest and its context.

Learning challenge: Overcoming or resolving "cognitive dissonance" between "romance as women's love story" and "romance as hero-story of quest, trial, and transcendence."

Many students understand these distinctions as instructor explains or reinforces them, but few exams or essays refer to the romance narrative (or they keep referring to romance exclusively as a love story), indicating that previous associations overpower the new information, which is not reinforced except in advanced literary studies.

Instructor continues to teach the difference for sake of preparing students who may encounter academic uses of the romance narrative in the future or the few who will remember it when they watch pop-culture narratives like action-adventure or science fiction movies, or read pop-culture narratives like popular novels or graphic novels.

Intellectual outcome: Romance is the essential narrative of popular literature, and since popular literature succeeds primarily on a surface level instead of an intellectual or critical level, only a few people can be expected to know or care, but they should!

![]()

Attributes of romance narrative:

![]() plot or

story-line: journey, quest, mission, pilgrimage of self-transformation or adventure

involving tests or trials that strengthen or refine and elevate the protagonist.

plot or

story-line: journey, quest, mission, pilgrimage of self-transformation or adventure

involving tests or trials that strengthen or refine and elevate the protagonist.

![]() separation & reunification as recurrent actions or cycles of trials and

tests (e.g., rescues, recoveries, escapes)

separation & reunification as recurrent actions or cycles of trials and

tests (e.g., rescues, recoveries, escapes)

![]() desire & loss as mechanisms for pushing the

romance narrative forward.

desire & loss as mechanisms for pushing the

romance narrative forward.

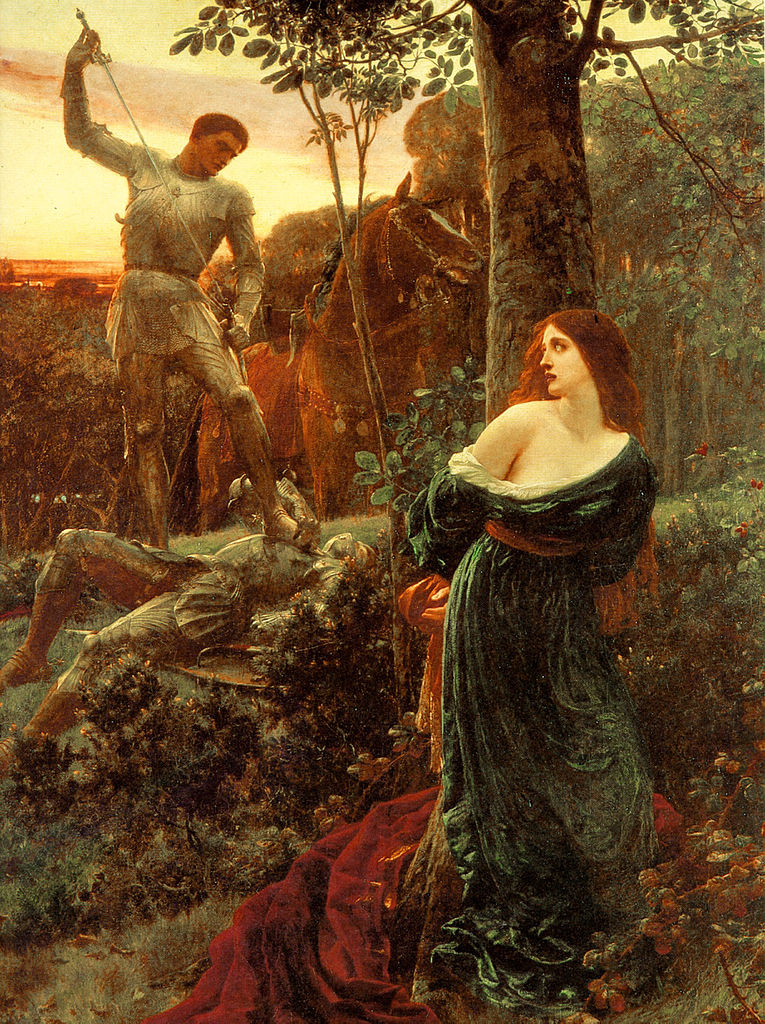

![]() characterization: simple, moralistic, symbolic: good guy-bad guy; fair

lady-dark lady; innocent child and corrupt adult (contrast

tragedy's mixed characters)

characterization: simple, moralistic, symbolic: good guy-bad guy; fair

lady-dark lady; innocent child and corrupt adult (contrast

tragedy's mixed characters)

![]() heroic individualism: "I guess it's up to me!"

heroic individualism: "I guess it's up to me!"

![]() settings:

extreme, idealized, long ago and far away or deep into the future or a

fantasy-world (contrast with realism, which

concentrates on here and now)

settings:

extreme, idealized, long ago and far away or deep into the future or a

fantasy-world (contrast with realism, which

concentrates on here and now)

![]() codes of

honor, chivalry, gallantry, purity (or these qualities oppositional

counterparts: shame, indecency, base motives)

codes of

honor, chivalry, gallantry, purity (or these qualities oppositional

counterparts: shame, indecency, base motives)

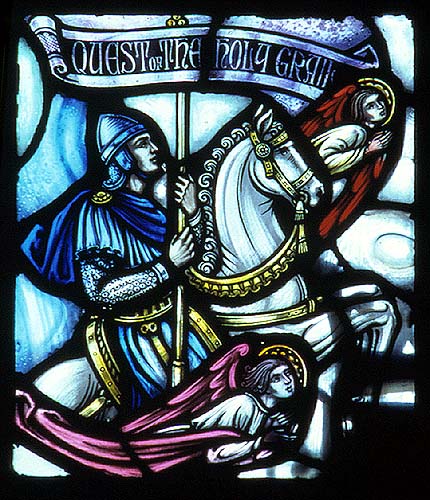

![]() conclusion as transcendence (or

escape or deliverance from prior struggle): The fairy tale

as a romance narrative concludes with conflicts ended

and the couple "living happily ever after." In tales of chivalry, the knight slays the dragon, wins

the hand of the fair lady, or sees the Holy Grail. In westerns, the cowboy cleans up the town

and (maybe with his girl) "rides off into the sunset." Rambo or some

other action hero flies off in his helicopter or drives off in his hot car. Also, "Let's

get away from it all."

conclusion as transcendence (or

escape or deliverance from prior struggle): The fairy tale

as a romance narrative concludes with conflicts ended

and the couple "living happily ever after." In tales of chivalry, the knight slays the dragon, wins

the hand of the fair lady, or sees the Holy Grail. In westerns, the cowboy cleans up the town

and (maybe with his girl) "rides off into the sunset." Rambo or some

other action hero flies off in his helicopter or drives off in his hot car. Also, "Let's

get away from it all."

![]()

Protagonists are motivated by desire for fulfillment or a vision of transcendent grace; cf. desire and loss.

-

romantic comedy or upbeat romance: the couple is elevated to a transcendent moment like a wedding or dance; or the macho hero honorably vanquishes his dishonorable antagonist.

-

tragic romance: the hero or couple desires a goal so high or daring as to be forbidden > tragic loss!

-

yet the vision survives, renewing the romance cycle of desire and loss

-

![]()

Taken

as "romance narrative":

hopefully happy family separated by evil intruder;

super-dad or

hero-brother avenges evil,

rescues & reunifies family's lost

children,

transcends to "happily ever after"

(or until the next sequel)

|

|

|

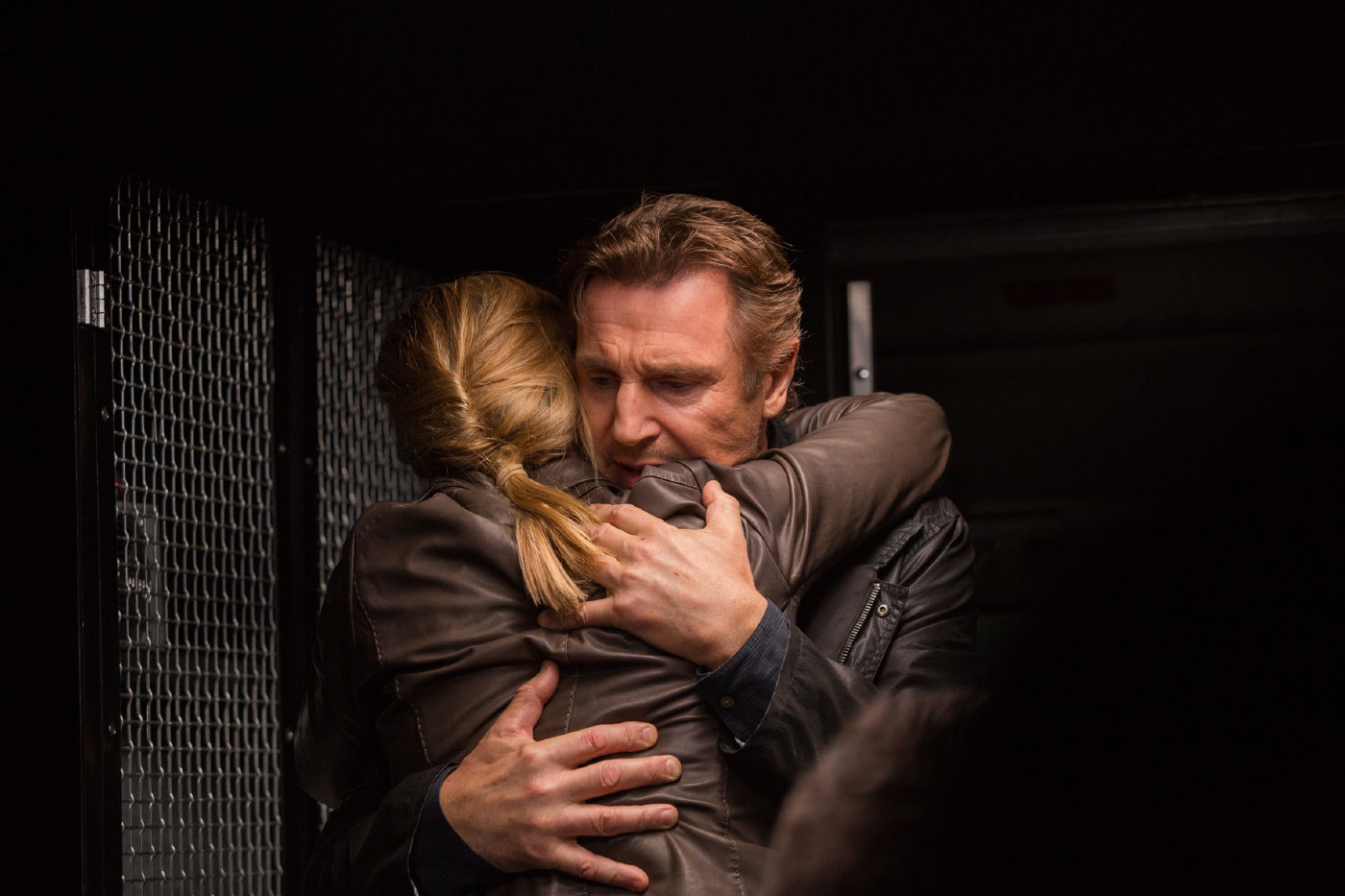

Visuals below: The romance narrative's most familiar origin is that of the medieval knight on a quest, sometimes for a transcendent vision of the Holy Grail (Christ's communion cup), signifying purity of heart and devotion to service. That service often involved rescuing fair ladies (damsels in distress) from impure or villainous rivals.

|

|

|

![]()

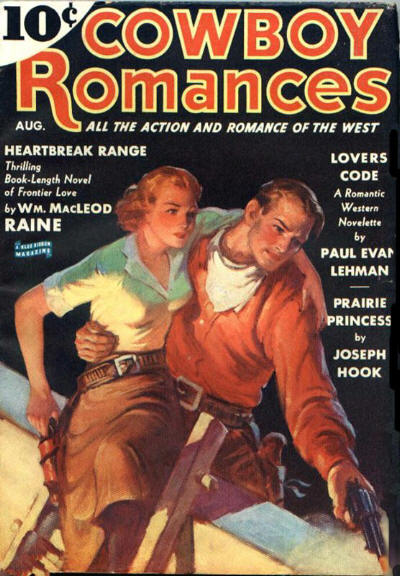

Below: A popular American variant on the romance narrative is the Western. Good guys wear white hats instead of shining armor and bad guys wear black hats instead of appearing as the "dark knight" or "black knight." Again characters are starkly divided into good and bad, and love-romance involving rescues of women are common.

One way to tell good guys and bad guys apart in Westerns and other masculine romance-adventures is that good guys are polite or "chivalrous" toward women, while bad guys may threaten dishonor or abuse to women.

|

|

|

Below: Science fiction stories resemble tales of western cowboys and medieval knights by using romance narrative and characterization. Fairly all science fiction novels are romances. H.G. Wells, one of the "fathers of science fiction," referred to his science fiction novels as "scientific romances"

Below at left, Darth Vader as the black knight (of the darkside) battles the good and pure Luke Skywalker, a "Jedi Knight."

Below at right, love-romance continues to feature but does not necessarily define or limit the romance narrative.

|

|

|

Below: Gender-bending in recent romance narratives (Hunger Games, Game of Thrones) features women characters as heroic individuals using men's weapons on their own quests and not waiting to be rescued.

|

|

|

![]()

The romance narrative derives primarily from Europe or Eurasia. How does it adapt to an American setting?

Western movies:

- cowboys as mounted knights

- white hats and

black hats as good guy-bad guy color code

- codes of honor, chivalry towards women

Compare "frontier romances" like The Leatherstocking Tales (e.g. The Last of the Mohicans)

Country & Western music: are singers troubadours?

Batman and Robin—"the Dark Knight"

![]()

fantasy-based reality competition series on ABC TV

network 2014-15

Definitions:

from A Handbook to Literature, by C. Hugh Holman (3d ed.), Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1972.

Romance: This word was first used for Old French as a language derived from Latin or "Roman" [now known as "romance languages" incl. Spanish, French, Italian] to distinguish it from Latin itself . . . . Later romance was applied to any work written in French, and as stories of knights and their deeds were the dominant form of Old French Literature, the word romance was narrowed to mean such stories. . . . Special modern uses of the word romance may be noted from the account in the New English Dictionary: "romantic fiction"; "an extravagant fiction"; a "fictitious narrative in prose of which the scene and incidents are very remote from those of ordinary life" . . . .

![]()

from Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957.

In the form in which we possess it, most of

[European fiction] has already moved into the category of romance.

Romance divides into

two main forms: a secular form dealing with chivalry

and knight-errantry, and a religious form devoted to legends of saints.

Both lean heavily on miraculous violations of natural law for their

interest as stories. (34)

![]()

For Literature of the Future: how the Bible's Book of Revelation may embody or resemble a romance narrative

Purpose: Though the future predicted by Revelation is falsified by the history of fairly every generation for two thousand years, Revelation remains perhaps the most popular book of the Bible, especially among Evangelical and Fundamentalist Christians, owing largely to its vivid imagery, suggestive symbolism, and other literary features, but also for promising deliverance for the faithful (i.e., the believing reader) and suffering to non-believers or other enemies.

2. Narrative genres: How does the plot-pattern of Revelation resemble the plot narrative of a romance? Pay attention to the gradual revelation of the central character of Jesus—how does he appear? How is he like a hero in a romance-rescue story? How are the Satanic figures like the villain? (instructor will lead)

The "romance narrative" in literary terms is not necessarily about love.

In its simplest form, the "romance narrative" follows this basic sequence or structure

situation, relationships apparently normal

![]()

outside force disrupts

![]()

hero begins quest to resolve or restore

![]()

hero and other characters endure tests / trials

![]()

hero achieves goal, rescues, reunites > transcendence

The Creation-Apocalypse narrative embodies the romance narrative in the following terms (more or less)

previous state of perfection: Garden of Eden, Christ among the Apostles, or Apostolic era

![]()

fall, separation (Adam & Eve exiled from Eden, cursed to labor; Christ crucified, resurrected, ascended; disciples left to own leadership)

![]()

disasters build on each other > state of sin, believers beset by struggle, opposition

![]()

rescue by hero = savior

![]()

restoration of previous state (tree of life restored in heaven)

Other ways Revelation fuffills the romance narrative: clear distinction between good heroes (light, order) and evil antagonists (dark, disorder), in contrast to tragedy, where characters are mixtures of good and bad.

thanks to https://slideplayer.com/slide/7246759/