|

Craig White's Literature Courses Historical Backgrounds Neo-Classical or Enlightenment Architecture (period and style) a.k.a. "Greek Revival" (compare Baroque & Romantic architecture) |

digital recreation of original Parthenon, 5c Greece |

As with many values and practices of the Enlightenment, architecture of the late 1600s, 1700s and beyond imitated models from classical Greece and Rome--therefor the descriptive terms "Neo-Classical" and "Greek Revival," with many variations.

The rigorous simplicity of this architectural movement reacted against overly decorative-to-decadent features of Baroque and Rococo architecture but also extended some classicizing qualities of the Baroque such as symmetry, balance, or counterpoint.

In general, though, Neo-Classical architecture differs from Baroque by its comparative starkness, diminished interplay of light and shadow, and isolation of individual features or ornaments in frames or corners.

Neo-Classical architecture often has a heavier feel than the ascending lightness of the Baroque, giving it a sense of gravity or power.

Neo-Classical architecture associated with early United States and France after its Revolution, both of which saw classical architecture as embodying the spirit of Athenian democracy and the Roman republic.

![]()

Classical Greek & Roman Architecture

The Parthenon (447-38 BCE), Athens Greece

![]()

Temple of Hephaestos (449-44 BCE), Athens

![]()

Maison Carree, Nimes, France (16 BCE)

(Roman temple rededicated to

Christianity 4c CE)

![]()

Neo-Classical or Greek Revival Architecture

in Europe

(late 1600s-1700s +)

Gucevicius, Vilnius Cathedral, Lithuania (1783-89)

![]()

Juan de Villanueva, El Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain (1785)

![]()

Neo-Classical or Greek Revival Architecture

in

North America

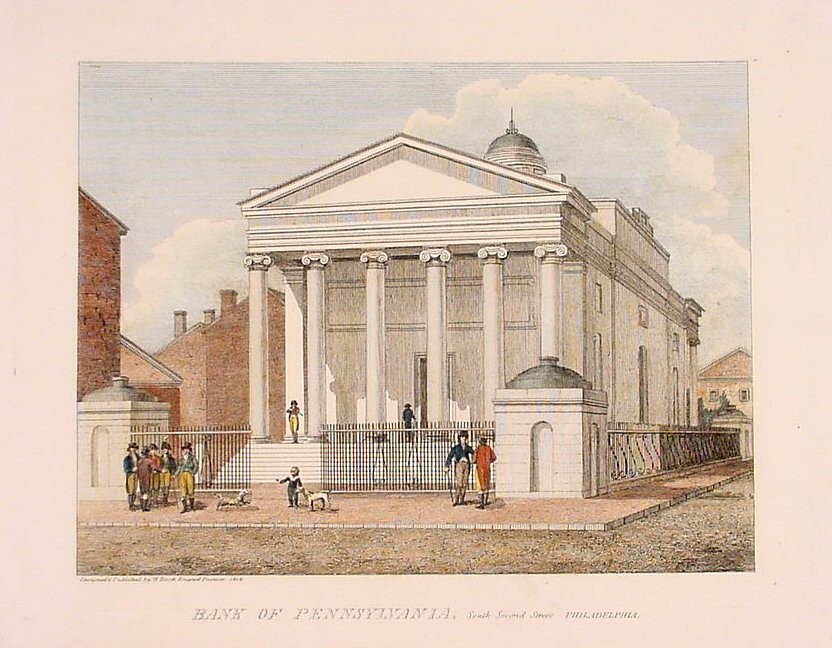

Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820), Bank of Pennsylvania (1780)

![]()

Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764-1820), Latrobe Gate, Washington Navy Yard (1806, 1881)

![]()

Latrobe, Baltimore Basilica (1806-1820)

![]()

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), Monticello (early 1800s) (Palladian style)

![]()

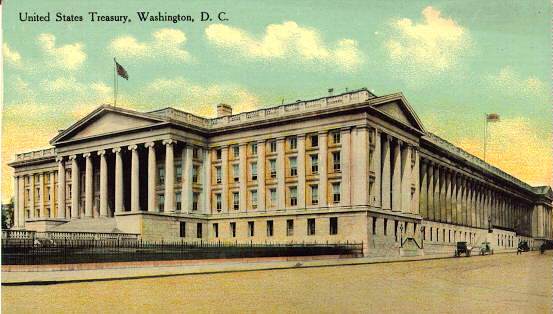

Robert Mills (1781-1855), U.S. Treasury Building (1839-69)

![]()

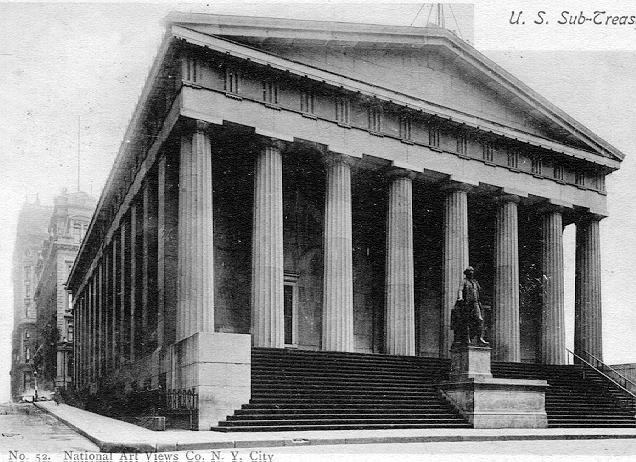

Town, Davis, & Frazee, New York Custom House (1833-42)

![]()

First Baptist Church, Mobile, Alabama

![]()

Central Baptist Church, Miami FL

![]()

U.S. Capitol (1800s-present)

![]()

John Russell Pope (1874-1937), Thomas Jefferson

Memorial (1939-43)