|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) from The Autobiography (first published in French translation,

1791; |

|

Instructor's note: These selections are only a fraction of Franklin's entire autobiography, which was drafted at two or more stages of his life and left incomplete at his death, but these passages are among those remembered and discussed by students of early American literature and history.

Selections follow three criteria:

![]() literary

interest, esp. Franklin's discussions of his experiments with new forms

of journalism, and of his own reading in developing forms like the

novel or

fiction, or

discussions of Deism;

literary

interest, esp. Franklin's discussions of his experiments with new forms

of journalism, and of his own reading in developing forms like the

novel or

fiction, or

discussions of Deism;

![]() history

of ideas & events, esp. Franklin's physical and intellectual journey from

late Puritan Boston to

Enlightenment

Philadelphia, including the transition of early North America from New

England colony centered on religion to an expanding empire propelled by

materialism and capitalism;

history

of ideas & events, esp. Franklin's physical and intellectual journey from

late Puritan Boston to

Enlightenment

Philadelphia, including the transition of early North America from New

England colony centered on religion to an expanding empire propelled by

materialism and capitalism;

![]() famous

episodes often featured in discussion of Franklin's life and writings.

famous

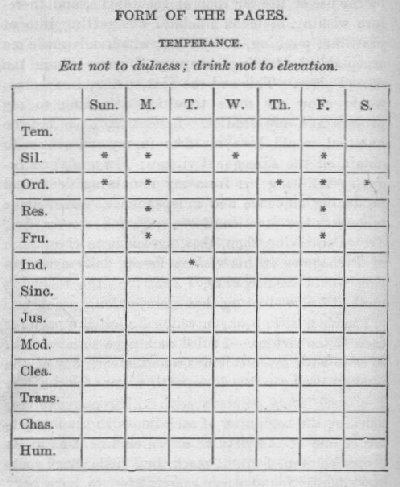

episodes often featured in discussion of Franklin's life and writings.

Throughout the 1800s and early twentieth century, Franklin's Autobiography was standard assigned reading for schoolboys, who were taught to regard Franklin as a rags-to-riches story that fulfilled the American Dream of financial success and civic leadership. For a satire on such readings, see Mark Twain, "The Late Benjamin Franklin" (1870).

Pleasure in Franklin's text increases with familiarity and repeated reading. He rambles briefly but overall writes plainly and purposefully. His most characteristic literary talent may be his combination of honesty, discretion, wit, and irony with which he represents a life that many people already revered.

Students sometimes regard Franklin's Autobiography as boastful, but his occasional acknowledgements of his many accomplishments are mostly factual and brief. He may understate more than overstate. Average minds (mine included) can only begin to fathom the range, depth, and seriousness of his mind and abilities.

![]()

from Franklin's Autobiography

[1]

.

. . To return: I continued thus employed in my father's business

[candle-making]

for two years, that is, till I was twelve years old; and . . .

there was all appearance that I was destined to supply

[take]

his

place, and become a tallow-chandler

[candle-maker].

But my dislike to the trade continuing, my father was under apprehensions that

if he did not find one for me more agreeable, I should break away and get to

sea, as his son Josiah had done, to his great vexation.

[compare

Robinson Crusoe]

He

therefore sometimes took me to walk with him, and see joiners

[carpenters],

bricklayers, turners, braziers

[fire-stokers],

etc., at their work, that he might observe my inclination, and endeavor to fix

it on some trade or other on land.

[2]

It

has ever since been a pleasure to me to see good workmen handle their tools; and

it has been useful to me, having learnt so much by it as to be able to do little

jobs myself in my house when a workman could not readily be got, and to

construct little machines for my experiments, while the intention of making the

experiment was fresh and warm in my mind.

My father at last fixed upon the cutler's trade

[making cutlery =

silverware, knives, etc.],

and my uncle Benjamin's son Samuel, who was bred to that business in London,

being about that time established in Boston, I was sent to be with him some time

on liking. But his expectations of a fee with me displeasing my father, I was

taken home again.

[Cousin

Samuel, a master cutler, expects payment for training Ben as an

apprentice.]

[3]

From

a child I was fond of reading, and all the little money that came into my hands

was ever laid out in books.

Pleased with the

Pilgrim's Progress

[see para. 23

below], my first collection was of John Bunyan's works in

separate little volumes. . . . My

father's little library consisted chiefly of books in polemic divinity

[religious controversy],

most of which I read, and have since often regretted that, at a time when I had

such a thirst for knowledge, more proper books had not fallen in my way since it

was now resolved I should not be a clergyman.

[<note BF’s shift from

religious to classical and practical learning>]

Plutarch's Lives

there was in which I read abundantly, and I still think

that time spent to great advantage. There was also

a book of De Foe's

[author of

Robinson Crusoe], called an Essay on

Projects

[projects = public works],

and another of Dr. Mather's, called

Essays to do Good, which perhaps gave me a turn of thinking that had an

influence on some of the principal future events of my life.

[Times are changing:

Puritan author is read not for sovereignty of God but for self-reliance.]

[4]

This

bookish inclination at length determined my father to make me a printer,

though he had already one son (James) of that profession. In 1717 my brother

James returned from

[5]

I

was to serve as an apprentice till I was twenty-one years of age, only I was to

be allowed *journeyman's wages during the last year.

In a

little time I made

[gained]

great proficiency in the business, and became a useful hand

to my brother. I now had access to

better books.

An acquaintance with the apprentices of

booksellers enabled me sometimes to borrow a small one, which I was careful

to return soon and clean. Often I sat up in my room reading the greatest part of

the night, when the book was borrowed in the evening and to be returned early in

the morning, lest it should be missed or wanted.

[6]

And

after some time an ingenious

[clever]

tradesman, Mr. Matthew Adams, who had a pretty

[appreciable]

collection of books, and who frequented

[regularly visited]

our printing-house, took notice of me, invited me to his

library, and very kindly lent me such books as I chose to read.

I now took a fancy to poetry, and

made some little pieces; my brother,

thinking it might turn to account, encouraged me, and put me on composing

occasional ballads.

[<ballads on current

events]

One was called The Lighthouse Tragedy, and contained an

account of the drowning of Captain Worthilake, with his two daughters: the other

was a sailor's song, on the taking of Teach (or

Blackbeard) the pirate. They were

wretched stuff, in the *Grub-street-ballad style

;

and when they were printed he sent me about the town to sell them.

[*Grub Street =

[7]

The

first sold wonderfully, the event being recent, having made a great noise. This

flattered my vanity; but my father discouraged me by ridiculing my performances,

and telling me verse-makers were generally beggars. So I escaped being a poet,

most probably a very bad one; but as

prose writing had been of great use to me in the course of my life, and was

a principal means of my advancement, I shall tell

you how, in such a

situation, I acquired what little ability I have in that way.

[8]

There was another bookish lad in the town

[Boston],

John Collins by name, with whom I was intimately acquainted. We sometimes

disputed, and very fond we were of

argument

[debating],

and very desirous of confuting

[disproving]

one

another, which disputatious

[argumentative]

turn, by the way, is apt to become a very bad habit, making people often

extremely disagreeable in company by the contradiction

[difference of opinion]

that is necessary to bring it into practice; and thence,

besides souring and spoiling the

conversation, is productive of disgusts

[bad feelings]

and,

perhaps enmities

[feuds]

where you may have occasion for friendship.

I had caught it by

reading my father's books of dispute about religion. Persons of good sense,

I have since observed, seldom fall into it, except lawyers, university men, and

men of all sorts that have been bred at Edinborough.

[<i.e., Scots people,

who enjoy a wide reputation for arguing or differing.]

[9]

A

question [debate

topic]

was once, somehow or other, started between Collins and me,

of the propriety of educating the female

sex in learning, and their abilities for study.

[<a frequent

Enlightenment topic ]

He was of opinion that it was improper, and that they were

naturally

unequal to it. I took the contrary side, perhaps a little for dispute's sake. He

was naturally more eloquent, had a ready plenty of words; and sometimes, as I

thought, bore me down more by his fluency than by the strength of his reasons.

[10]

We parted without settling the point, and were not to see

one another again for some time, I sat down to

put my arguments in writing, which I

copied fair and sent to him. He answered, and I replied. Three or four letters

of a side had passed, when my father

happened to find my papers and read them. Without entering into the

discussion

[putting aside the

topic],

he took occasion to talk to me about the

manner of my writing; observed that, though I had the advantage of my

antagonist in correct spelling and pointing (which I owed to the

printing-house), I fell far short in elegance of expression, in method and in

perspicuity, of which he convinced me by several instances.

I saw the justice

of his remark, and thence grew more attentive to the manner in writing, and

determined to endeavor at improvement.

[11]

About this time I met with

an odd volume of the Spectator

[elite

[12]

Then I compared my

Spectator with the original, discovered some of my faults, and corrected

them. But I found I wanted a stock of words

[i.e., vocabulary],

or a readiness in recollecting and using them, which I thought I should have

acquired before that time if I had gone on making verses; since the continual

occasion for words of the same import, but of different length, to suit the

measure, or of different sound for the rhyme, would have laid me under a

constant necessity of searching for variety, and also have tended to fix that

variety in my mind, and make me master of it.

Therefore I took some of the tales and

turned them into verse; and, after a time, when I had pretty well forgotten the

prose, turned them back again.

[<note tendency to

experiment; also he doesn’t treat the writings as inviolable scripture but as

human-made products that he can also produce>]

[13]

I also sometimes jumbled my collections of hints into

confusion, and after some weeks endeavored to reduce them into the best order,

before I began to form the full sentences and complete the paper. This was to

teach me method in the arrangement of

thoughts. By comparing my work afterwards with the original, I

discovered many faults and amended them;

but I sometimes had the pleasure of fancying that, in certain particulars of

small import, I had been lucky enough to improve the method or the language, and

this encouraged me to think I might possibly in time come to be a tolerable

English writer, of which I was extremely ambitious.

[14]

My time for these exercises and for reading was at night,

after work or before it began in the morning, or on Sundays, when I contrived to

be in the printing-house alone, evading

as much as I could the common attendance on public worship which my father used

to exact on me when I was under his care, and which indeed I still thought a

duty, though I could not, as it seemed to me, afford time to practise it.

[15]

When about 16 years of age I happened to meet with a book,

written by one Tryon, recommending a

vegetable

[vegetarian]

diet.

I determined to go into it. My brother, being yet unmarried, did not keep house,

but boarded

[provided food for]

himself and his apprentices in another family. My refusing to eat flesh

occasioned an inconveniency, and I was frequently chid

[chided, scolded]

for

my singularity. I made myself acquainted with Tryon's manner of preparing some

of his dishes, such as boiling potatoes or rice, making hasty pudding

[cf. cream of wheat],

and a few others, and then proposed to my brother, that

if he would give me, weekly, half the

money he paid for my board

[feeding],

I would board myself. He instantly agreed to it, and I presently found that I

could save half what he paid me.

This was

an additional fund for buying books.

[16]

But I had another

advantage in it. My brother and the rest going from the printing-house to

their meals, I remained there alone, and, dispatching presently my light repast

[finishing quickly my light meal],

which often was no more than a biscuit or a slice of bread, a handful of raisins

or a tart [fruit

pie]

from the pastry-cook's, and a glass of water,

had the rest of the time till their

return for study, in which I made the greater progress, from that greater

clearness of head and quicker apprehension which usually attend temperance in

eating and drinking.

[<compare modern

over-achiever’s habit of “lunch at my desk”]

[17]

And now it was that,

being on some occasion made ashamed of

my ignorance in figures

[numbers, math],

which I had twice failed in learning when at school, I took Cocker's book of

Arithmetic, and went through the whole by myself with great ease.

I also read Seller's and Shermy's books

of Navigation, and became acquainted with the little

geometry they contain; but never

proceeded far in that science. And I read about this time

Locke On Human

Understanding, and the Art of Thinking, by Messrs. du

[18]

While I was intent on improving my language, I met with

an English grammar (I think it was

Greenwood's), at the end of which there were two little

sketches of the arts of rhetoric and

logic, the latter finishing with a specimen of a dispute in

the Socratic method; and soon after

I procured Xenophon's Memorable Things of Socrates, wherein there are many

instances of the same method.

[Memorabilia

by Xenophon, 4C BCE Greek Historian]

I

was charmed with it, adopted it, dropped my abrupt contradiction and positive

argumentation, and put on the humble inquirer and doubter.

[Instead of

putting himself forward as right and making others wrong, that is,

[19]

And being then,

from reading Shaftesbury and Collins

[Anthony

Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713); Anthony Collins

(1676-1729), advocate of Deism],

become a real doubter

[skeptic]

in

many points of our religious doctrine,

I found this

[Socratic]

method safest for myself and very embarrassing to those against whom I used it;

therefore I took a delight in it

[Socratic method],

practiced it continually, and grew

very

artful and

expert in drawing people, even of superior knowledge, into concessions,

the consequences of which they did

not foresee, entangling them in

difficulties out of which they could not extricate themselves, and so obtaining

victories that neither myself nor my cause always deserved.

[20]

I continued this method some few years, but gradually left

it, retaining only the habit of

expressing myself in terms of modest diffidence

[discretion];

never using,

when I advanced any thing that may possibly be disputed, the words certainly,

undoubtedly, or any others that give the air of positiveness to an opinion; but

rather say, I conceive or apprehend a thing to be so and so; it appears to me,

or I should think it so or so, for such and such reasons; or I imagine it to be

so; or it is so, if I am not mistaken.

[21]

This

habit, I believe, has been of great advantage

to me when I have had occasion to inculcate my opinions, and persuade men into

measures

[decisions, actions]

that I have been from time to time engaged in promoting;

and, as the chief ends of conversation

are to inform or to be informed, to please or to persuade, I wish well-meaning,

sensible men would not lessen their power of doing good by a positive, assuming

manner, that seldom fails to disgust, tends to create opposition, and to defeat

every one of those purposes for which speech was given to us, to wit, giving or

receiving information or pleasure.

[to entertain and

instruct]

[22]

For, if you would inform,

a positive and dogmatical

[strongly opinionated]

manner in advancing your sentiments may provoke contradiction

and prevent a candid attention. If you wish information and improvement from the

knowledge of others, and yet at the same time express yourself as firmly fixed

in your present opinions, modest,

sensible men, who do not love disputation, will probably leave you undisturbed

in the possession of your error. And by such a manner, you can seldom hope

to recommend yourself in pleasing your hearers, or to persuade those whose

concurrence you desire.

![]()

Instructor’s note:

On the way

![]() John Bunyan (English Puritan, 1628-88),

The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678,

1684), a Christian allegory whose style anticipates the realistic novel

a generation later.

John Bunyan (English Puritan, 1628-88),

The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678,

1684), a Christian allegory whose style anticipates the realistic novel

a generation later.

![]() Daniel Defoe (1659-1731),

The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

(1719), widely regarded as the first English novel;

Moll Flanders (1722)

Daniel Defoe (1659-1731),

The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

(1719), widely regarded as the first English novel;

Moll Flanders (1722)

![]() Samuel Richardson (1689-1761),

Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded (1740)

Samuel Richardson (1689-1761),

Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded (1740)

[23]

In

crossing the bay, we met with a squall

[storm]

that tore our rotten sails to pieces, prevented our getting

into the Kill and drove us upon

[24]

I

have since found that it [Pilgrim’s

Progress]

has been translated into most of the languages of

|

|

|

![]()

Instructor’s

note: A later comment by

[25]

I believe I have omitted mentioning that, in my first

voyage from

[26]

I

balanced some time between principle and inclination,

till I recollected that, when the fish

were opened

[cut open],

I saw smaller fish taken out of their stomachs; then thought I, "If you eat one

another, I don't see why we mayn't eat you." So I dined upon cod very heartily,

and continued to eat with other people, returning only now and then occasionally

to a vegetable

[vegetarian]

diet.

So convenient a thing is it to be a

reasonable creature, since it

enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.

[

![]()

Instructor’s note:

recalling Franklin’s comments on fiction a few paragraphs above

[24], note that his entrance to Philadelphia (though

lacking direct representation of dialogue) has some features associated with

fiction, such as the human “figure,” scene, and social encounter, especially in

a public street or road—See

Bakhtin’s

chronotope of the road.

[27]

I have been the

more particular in this description of my journey, and shall be so of my

first entry into that city

[

[28]

Then

I walked up the street,

gazing about till near the market-house I

met a boy with bread. I had made

many a meal on bread, and, inquiring

where he got it, I went immediately to the baker's he directed me to, in

Secondstreet, and asked for biscuit, intending such as we had in Boston; but

they, it seems, were not made in Philadelphia. Then I asked for a three-penny

loaf, and was told they had none such. So not considering or knowing the

difference of money, and the greater cheapness nor the names of his bread, I

made him give me three-penny worth of

any sort. He gave me, accordingly, three great puffy rolls. I was surprised at

the quantity

[<comic excess],

but took it, and, having no room in my pockets, walked off with a roll under

each arm, and eating the other.

[<comic

incongruity]

[29]

Thus

I went up Market-street as far as Fourth-street, passing by the door of Mr.

Read, my future wife's father; when she, standing at the door, saw me, and

thought I made, as I certainly did, a most awkward, ridiculous appearance. Then

I turned and went down Chestnut-street and part of Walnut-street, eating my roll

all the way, and, coming round, found myself again at Market-street wharf, near

the boat I came in, to which I went for a draught of the river water; and, being

filled with one of my rolls, gave the other two to a woman and her child that

came down the river in the boat with us, and were waiting to go farther.

[30]

Thus refreshed, I

walked again up the street, which by this time had many clean-dressed people in

it, who were all walking the same way. I joined them, and thereby was led into

the great meeting-house of the Quakers near the market. I sat down among

them, and, after looking round awhile and hearing nothing said

[“silent meeting”

typical of early Quakers],

being very drowsy thro' labor and want of rest the preceding night,

I fell fast asleep, and continued so

till the meeting broke up, when one was kind enough to rouse me. This was,

therefore,

the first house I was in, or slept in, in

[31]

Before I enter upon my public appearance in business, it

may be well to let you know the then state of my mind with regard to

my principles and morals, that you

may see how far those influenced the future events of my life. My parents had

early given me religious impressions, and brought me through my childhood

piously in the Dissenting

[Puritan]

way.

[32]

But I was scarce

fifteen, when, after doubting by turns of several points, as I found them

disputed in the different books I read, I began to doubt of Revelation itself.

Some books against

Deism—fell

into my hands . . . . It happened that they

wrought an effect on me quite contrary

to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were

quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in

short, I soon became a thorough Deist.

[33]

My

arguments perverted some others, particularly Collins and Ralph

[friends in his reading

club];

but, each of them having afterwards wronged me greatly without the least

compunction, and recollecting Keith's conduct towards me (who was another

free-thinker

[religious skeptic]),

and my own

[conduct]

towards Vernon

[?]

and

Miss Read

[future wife],

which at times gave me great trouble,

I began to suspect

that this doctrine, though it might be true, was not very useful. . . .

[34]

I grew convinced that truth,

sincerity and

integrity in dealings between

man and man were of the utmost importance to the felicity

[happiness]

of life; and I

formed written resolutions, which still remain in my journal book, to practice

them ever while I lived.

Revelation

[scripture or

tradition]

had

indeed no weight with me,

as such; but I entertained an

opinion that, though certain actions might not be bad

because they were

forbidden by it, or good because

it commanded them, yet probably these actions might be forbidden

because they were bad for us,

or commanded because

they were beneficial to us, in their own

natures, all the circumstances of things considered.

[

[35]

And this

persuasion, with the kind hand of

Providence, or some guardian angel,

or accidental favorable

circumstances and situations, or all together, preserved me, through this

dangerous time of youth, and the hazardous situations I was sometimes in among

strangers, remote from the eye and advice of my father, without any willful

gross immorality or injustice, that might have been expected from my want of

religion. . . .

[36]

I

had been religiously educated as a Presbyterian

[a Congregationalist or

Puritan, in this usage];

and though some of the dogmas

[doctrines]

of

that persuasion

[belief system],

such as the eternal decrees of God, election, reprobation, etc., appeared to me

unintelligible, others doubtful

[questionable],

and I early absented myself from the public assemblies of the sect

[religious faction],

Sunday being my studying day, I

never was without some religious

principles. I never doubted, for instance, the existence of the Deity; that

he made the world, and governed it by his

[37]

These I esteemed the essentials of every religion; and, being to be found in all

the religions

we had in our country, I respected them

all, though with different degrees of respect, as I found them more or less

mixed with other articles, which, without any tendency to inspire, promote, or

confirm morality, served principally to

divide us, and make us unfriendly to one another. This respect to all, with

an opinion that the worst had some good effects, induced me to

avoid all discourse that might tend to

lessen the good opinion another might have of his own religion; and as our

province increased in people, and new places of worship were continually wanted,

and generally erected by voluntary contributions, my mite

[small contribution]

for

such purpose, whatever might be the sect

[denomination],

was never refused.

[38]

Though I seldom attended any public worship, I had still an

opinion of its propriety, and of its utility when rightly conducted, and I

regularly paid my annual subscription for the support of the only Presbyterian

minister or meeting we had in

![]()

Instructor’s note:

[39]

It was about this time I conceived the bold and arduous

project of arriving at moral perfection. I wished to live without committing any

fault at any time; I would conquer all

that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into. As I

knew, or thought I knew, what was right and wrong, I did not see why I might not

always do the one and avoid the other. But I soon found I had undertaken a task

of more difficulty than I had imagined. While my care was employed in guarding

against one fault, I was often surprised by another; habit took the advantage of

inattention; inclination was sometimes too strong for reason. I concluded, at

length, that the mere speculative conviction that it was our interest to be

completely virtuous, was not sufficient to prevent our slipping; and that the

contrary habits must be broken, and good

ones acquired and established, before we can have any dependence on a

steady, uniform rectitude of conduct. For this purpose I therefore contrived the

following method. . . .

[40]

. .

. I included under thirteen names of

virtues all that at that time occurred to me as necessary or desirable, and

annexed to each a short precept, which fully expressed the extent I gave to its

meaning.

These names of virtues, with their precepts

[rules of conduct],

were:

1. TEMPERANCE.

Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

2. SILENCE.

Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

3. ORDER. Let

all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

4. RESOLUTION.

Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

5. FRUGALITY.

Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

6. INDUSTRY.

Lose no time; be always employ'd in something useful; cut off all unnecessary

actions.

7. SINCERITY.

Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak

accordingly.

8. JUSTICE.

Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

9. MODERATION.

Avoid extreams; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

10. CLEANLINESS.

Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.

11. TRANQUILITY.

Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

12. CHASTITY.

Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dulness, weakness, or

the injury of your own or another's peace or reputation.

13. HUMILITY.

Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

[classic instance of

Christian Humanism]

[41]

My intention being to acquire the habitude

[customary practice]

of all these

virtues, I judged it would be well not to distract my attention by attempting

the whole at once, but to fix it

[my attention]

on

one of them

[the 13 virtues]

at a

time; and, when I should be master of that, then to proceed to another, and so

on, till I should have gone through the thirteen;

and, as the previous acquisition of some might facilitate the acquisition of

certain others, I arranged them with that view, as they stand above.

[42]

Temperance first,

as it tends to procure that coolness and clearness of head, which is so

necessary where constant vigilance was to be kept up, and guard maintained

against the unremitting attraction of ancient habits, and the force of perpetual

temptations.

[43]

This

being acquired and established, Silence would be more easy;

and my desire being to gain knowledge at the same time that I improved in

virtue, and considering that in conversation it was obtained rather by the

use of the ears than of the tongue,

and therefore wishing to break a habit I

was getting into of prattling

[chattering],

punning, and joking,

which only made me acceptable to trifling company, I gave Silence the second

place.

[44]

This and the next, Order, I expected would allow me more

time for attending to my project and my studies. Resolution, once become

habitual, would keep me firm in my endeavors to obtain all the subsequent

virtues; Frugality and Industry freeing me from my remaining debt, and producing

affluence and independence, would make more easy the practice of Sincerity and

Justice, etc., etc. Conceiving then, that,

agreeably to the advice of Pythagoras in

his Golden Verses, daily examination would be necessary, I contrived the

following method for conducting that examination.

[Pythagoras = 6C

BCE Greek Philosopher and Mathematician;

The Golden Verses of Pythagoras are a collection of moral aphorisms

attributed to the philosopher.]

[45]

I

made a little book, in which I allotted a page for each of the virtues. I ruled

[drew lines on]

each page with red ink, so as to have seven columns, one

for each day of the week, marking each column with a letter for the day. I

crossed these columns with thirteen red lines, marking the beginning of each

line with the first letter of one of the virtues, on which line, and in its

proper column, I might mark, by a little

black spot, every fault I found upon examination to have been committed

respecting that virtue upon that day. . . .

[A set of tables systematizing

page of Franklin's little book of virtues

which historians have compared to an

account-book

[46]

I entered upon the execution of this plan for

self-examination, and continued it with occasional intermissions for some time.

I was surprised to find myself so much

fuller of faults than I had imagined; but I had the satisfaction of seeing them

diminish. . . . I transferred my tables and precepts to the ivory

[erasable]

leaves of a memorandum book, on which the lines were drawn with red ink, that

made a durable stain, and on those lines I marked my faults with a black-lead

pencil, which marks I could easily wipe out with a wet sponge. After a while I

went through one course only in a year, and afterward only one in several years,

till at length I omitted them entirely, being employed in voyages and business

abroad, with a multiplicity of affairs that interfered; but I always carried my

little book with me.

[47]

My

scheme of ORDER gave me the most trouble;

and I found that, though it might be practicable where a man's business was such

as to leave him the disposition of his time, that of a journeyman printer, for

instance, it was not possible to be

exactly observed by a master, who must mix with the world, and often receive

people of business at their own hours. Order, too, with regard to places for

things, papers, etc., I found extremely difficult to acquire. I had not been

early accustomed to it, and, having an exceeding good memory, I was not so

sensible of the inconvenience attending want of method. This article, therefore,

cost me so much painful attention, and my faults in it vexed me so much, and

I made so little progress in amendment,

and had such frequent relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the attempt,

and content myself with a faulty character in that respect . . .

[48]

And I believe this may have been the case with many, who,

having, for want of some such means as I employed, found the difficulty of

obtaining good and breaking bad habits in other points of vice and virtue, have

given up the struggle . . . ; for

something, that pretended to be reason, was every now and then suggesting to me

that such extreme nicety

[particularity]

as I

exacted of myself might be a kind of foppery

[dandyism,

affectedness]

in

morals, which, if it were known, would make me ridiculous; that a perfect

character might be attended with the inconvenience of being envied and hated;

and that a benevolent man should allow a

few faults in himself, to keep his friends in countenance

[friendly].

[49]

In truth, I found myself incorrigible with respect to

Order; and now I am grown old, and my memory bad, I feel very sensibly the want

of it. But, on the whole, though I never

arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far

short of it, yet I was, by the endeavor, a better and a happier man than I

otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it; as those who aim at

perfect writing by imitating the engraved copies, tho' they never reach the

wish'd-for excellence of those copies, their hand is mended by the endeavor, and

is tolerable while it continues fair and legible.

[

![]()