|

LITR 5439 Genre, Movement, Style

Summer 2015

1st

5-wks session |

Literary & Historical Utopias

Homepage & Syllabus URL: http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/5439utopia/default.html |

Instructor: Craig White Office:

Bayou 2529-7

Office Hours:

M & Th, 12-1, 6-6:30, and by appointment |

|

Course texts Thomas More, Utopia (1516) Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Herland (1915) Ayn Rand, Anthem (1938) Ernest Callenbach, Ecotopia (1975) Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake (2004) Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward, 2000-1887 (1887) Genesis, Revelation, & Book of Acts (BCE > 1st century AD/CE) Plato's Republic & Golden Age myths selections from other classic, multicultural, & postmodern texts |

Student Assignments midterm (30 June) research posts (2 + review in final; due 15-16 June; end of session) final exam (end of session)

Seminar presentations Model Assignment highlights from previous midterms, research posts, or final exams

|

Terms & Handouts

|

Utopia has historical and literary meaning: historical utopia = an experimental or "intentional community" intended to reform or escape from normal society, often by substituting planning, cooperation, or collective values and practices in place of freemarket competition and unenlightened individualism. literary utopia = a novel or tract (or shorter fiction) representing life and characters in such a community “Utopia” comes from Thomas More’s Utopia (1516). More coined the word from Greek parts, either ou (no) + topos (place, as in “topography”) to mean “no place” or eu (good, as in “euphoria”) + topos (place) to mean “good place” (Etymological confusion is consistent with generic instability of utopia / dystopia, serious or satirical.) Variations: Dystopia = society opposite from a utopia, or a utopia gone dysfunctional. (“Any utopia is someone else's dystopia.”) Ecotopia = Ecological Utopia, a community whose collective social health imitates nature’s interconnectivity—from Ecotopia, 1975 novel by Ernest Callenbach. (X) Millennium, apocalypse, or End-Times is often associated with utopian narratives, as when the biblical Book of Revelation ends with a vision of heaven (partly as restored Garden of Eden). |

Utopian Communities and Texts (list) Utopian Fiction & Experimental Communities in North America / USA (chronology) Standard features / conventions of utopian / dystopian literature Counter-Utopian (or anti-utopian) Tradition

|

Objectives

Objective 1. Utopian Genre

1a. How to define the literary genre of “utopias?” What are this genre's standard conventions or features? What attractions and detractions? What audiences are attracted or put off?

-

Utopian text as hybrid of novel (journey, dialogue, adventure, escape) and essay or tract (instruction / information, persuasion / propaganda, ethics / values, application). (entertain and instruct)

-

Utopias as hybrid of fiction and history, imagination and experience, idealism and reality.

1b. What genres join with or branch from utopia? Examples: dystopia, ecotopia, Socratic dialogue, science fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, novel / romance, adventure / travel narrative, journalism, tract, propaganda, satire. Others?

-

How interdependent are utopia and dystopia? (e.g., “Anyone's utopia is someone else's dystopia.”)

1c. Can utopias join science fiction, speculative fiction, and allied genres in a “literature of ideas?”

-

Can knowledge of utopian literature be applied to texts that are not exclusively utopian or dystopian?

1d. To identify the utopian author both within and beyond traditional literary categories—e.g., as writer + activist, agitator, reformer, prophet / visionary?

1e. Utopian aesthetics: How does Utopian Fiction rebalance literature's classical purpose to entertain and educate? Is utopian / dystopian literature more interesting to talk about than to read?

![]()

Objective 2. Utopian Narratives

2a. What narrative action rises from or fits the description of an ideal or dystopian community?—e. g., journey, dialogue, exploration, learning, liberation, conversion?

2b. What problems rise from a utopian story that minimizes conflict and maximizes equality and harmony? What genre variations derive from these problems with plot?

2c. What tensions between the author’s description of a social theory and the reader’s and author's need for a story?

2d. How essential is “millennialism” (apocalyptic or end-time event) to the utopian narrative?

2e. Does dialogue or dialectic of learning replace the traditional narrative of emergence, pursuit, love, revenge, etc.?

![]()

Objective 3. Historical / Cultural Objectives

Obj. 3 To get over the routine dismissal of utopias—"they don't work," “never happened,” or “castles in the sky”—and instead regard utopias as literary and historical experiments essential to Western Civilization and education.

3a.To review historical, nonfiction attempts by “communes,” “intentional communities,” nations, or cults to institutionalize or practice utopian ideals. What relations are there between fictional and actual utopian communities? What has been the historical impact of utopian fictions? Do utopian forms mirror and confirm social norms or oppose them?

3b. Are utopian impulses limited to socialism and communism, or may freemarket capitalism and democracy also express themselves in utopian terms and visions? Is utopia “progressive / liberal” or “reactionary / conservative?” What relations between “self and other” (us and them) are modeled? Does the utopian society model itself on past, present, or future? Does a utopia stop time, as with the millennial rapture or an achievement of perfection? Or can utopias change, evolve, and adapt to the changes of history?

3c. What social structures, units, or identities does utopia expose or frustrate?

-

Social units or structures: person/individual/self, gender, sex, family [nuclear or extended], community, village/town/city, class, ethnicity, farm, region, tribe, clan, union, nation, ecosystem, planet, etc.

-

How may utopian studies shift the usual American arguments over race, sex, faith, and gender to cultural and socio-economic class?

3d. How seriously to evaluate gender roles and standards of sexual and love relationships in utopian communities? How do these differ from or resemble traditional norms? How essential are such changes to their intended transformation of society?

-

What changes result in child-rearing, feeding, marriage, aging, sexuality, etc.?

3e. Since our major texts are set in North America, how do Americans regard utopias? What problems do the Founding and recent history of the USA present for utopian discussion? For example: socialism or communism, the Cold War and collapse of Stalinist-Maoist Communism; discussing alternative economic, reproductive, or child-rearing policies, the ascendance of religious and freemarket fundamentalism or American culture's stress on the family?)

-

Why do American school curricula emphasize dystopic fiction (Nineteen Eighty-Four, Brave New World, The Giver) over utopian fiction?

3f. Are utopias limited to Western Civilization, rationalism, and social engineering, or may they exemplify multiculturalism?

-

Is the utopian impulse universal or specific only to Western culture or civilization?

-

If utopias or millennia are detected in non-Western texts or traditions, are such terms appropriate, or do we simply project our identities and values on cultures that are in fact doing something else altogether?

![]()

Objective 4. Interdisciplinary Objectives

4a. What academic subjects or disciplines are involved with utopian studies? Examples: literature, history, sociology, economics, architecture, urban planning?

4b. How may utopian or millennial studies serve as an interdisciplinary subject of study? What strengths and weaknesses result from this status? (Comparable interdisciplinary subjects include women’s studies, gender studies, ethnic studies [e. g., African American studies, whiteness studies], future studies, millennialism.)

4c. Do some interdisciplinary subjects underprivilege multiculturalism? Do utopian studies privilege western civilization?

4c. Is “utopia” too simple and singular a word or concept for the variety of phenomena it describes? Conversely, what does utopia reveal about an author’s or culture’s cosmology or worldview, as well as cosmogonies or origin / creation stories?

4d. How do literature and literacy appear in utopian or dystopian cultures? Include computer literacy: What is a “virtual utopia” in science fiction and technology? How has utopian speculation, communication, and organization adapted to the Web? Does the Web itself assume utopian or millennial attributes? Can virtual reality appear utopian while actual reality becomes dystopian?

![]()

Objective 5. Instructional Objectives

5a. How may a seminar classroom serve as a microcosm, model, or alternative for American culture? How does use of web instruction alter social dynamics?

5b. What does utopian / dystopian literature instruct concerning education?

5c. What difficulties does utopian instruction typically present?

-

Preventing discussions from stalling on "Utopias don't work" or "Why are we talking about this?" (Utopian communities fail, but some people keep attempting or learning from utopias.)

-

Why do American curricula emphasize dystopias?

-

Since utopian studies offers so many non-literary subjects, how much to limit the discussion to literature or expand to interdisciplinary or social / political concerns?

5d. Can new sections of courses build on previous sections' accomplishments?

5e. Recurring conflicts in teaching literature: form or content? liberal or conservative ideology? Can studies of utopian literature confront these questions or conflicts more directly or dialectically?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Summer 2015 shedule

|

Readings: Genesis & Revelation; Acts; The Golden Age; Plato's Republic Presentation by 2013 LITR 5439 student Hannah Wells: Model Assignments; 2013 Utopias syllabus Discussion: Identify yourself and educational / career interests; what previous knowledge or reading of utopian / dystopian literature? Or related genres? Instructor's presentation: Brave New World +- Nineteen Eighty-Four |

Agenda:

welcome,

syllabus, website |

![]()

|

Readings: Thomas More, Utopia (1516)—read through book 1 & start book 2 Discussion starter for Book 1: Umaymah Shahid Web review: Thomas More sites : Michaela Fox Web review: Twin Oaks: Melissa Hodgkins |

Agenda:

roll, assignments, preview, presentations

Discussion: |

|

|

Assignments: Warning about Utopia: tedious reading, but clear and rewarding—"earned classic": could spend longer with it but may not want to. Work through Book 1 however you can and help each other out in discussion Tuesday. Discussion questions: 1. How does or doesn't Utopia resemble a novel? (Broadly, the "modern English novel" would not appear for two more centuries with DeFoe's Robinson Crusoe 1719). (Bakhtin 98) (genre) 2. As the novelistic passages are brief and dispersed, what other reading pleasures? Where does interest quicken or slacken, and why? What aspects of a novel are missing, and what happens instead? 3. What if any evidence of More as a Christian Humanist? Historical background to More's

Utopia

(1516):

Printing press developed 1450s (e.g., Gutenberg

Bibles)—More's traveler makes references to Utopians learning printing from

European visitors (2.32) |

|

![]()

|

Readings: complete Thomas More, Utopia (1516); begin C. P. Gilman, Herland, chs. 1-2. Discussion starter for Book Two of Utopia: Russell Lanier Discussion starter for Herland, chs. 1-2: instructor Model Assignment highlights (research posts): Lori Wheeler Instructor's presentation: B.F. Skinner, Walden Two (1948) + Los Horcones + Nudge |

Agenda: research post assignments Models: Lori Wheeler Utopia bk 2: Russell motivating utopia: pageantry (2.40), spectacle, emulation; property and family [break] begin Herland + (genre); action: formal genre of novel; back to More & Bakhtin conventions: journey, gardens, uniforms, irony / satire, Walden Two + (objs. 1a, 4a) |

|

|

Discussion Questions: Utopia: 1. What problems with characterization does utopian fiction generate? What balance of fictional entertainment and social instruction? What parts work best? What drives you crazy? What does the report leave out? 2. What conventions or set-pieces typify the utopian genre? One possibility: origin story when Utopus separates the island from the mainland. 3. Utopia's most threatening reforms may be abolition of private property, and reshaping of family relations. Are these two proposals related? Is family a form of property? 4. What textual evidence of More as a Christian Humanist? Herland: 1. What aspects of the novel or fiction are immediately evident? 2. Describe Gilman's prose style—what

advances in utopian fiction as fiction? |

|

![]()

|

Readings: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Herland (complete) Handout: "Charlotte Perkins Gilman," Handbook to American Women's History Discussion starter: Jan SmithWeb review: Charlotte Perkins Gilman sites; Feminist / Women's Utopias: Ashley Wrenn |

Agenda: research posts web: assignments disc: literature in literary utopias labor-credits in Walden Two & Twin Oaks; property / family as private 7.30, 8.97, 7.82, 9.57 > Woman on the Edge of Time |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. What conventions of utopian fiction

continue? Describe Gilman's prose style—what

advances in utopian fiction as

fiction? 3a. What conventions or innovations distinguish a feminist or women's utopia?

4. Associate Gilman and

Herland with the

Progressive Era, periods of progress as spawning utopias? 6. Herland appears in 1915, a half-century after Darwin's Origin of Species (1859). How does Darwinian or evolutionary thought appear in both the men's and women's attitudes and behavior—e.g., the advent of Parthenogenesis, the women's centuries-long cultivation or breeding, the men's defense of modern American economy as "Social Darwinism," in which an unregulated freemarket creates class struggle & "survival of the fittest."

6a. How may Darwinian utopias be compatible with Behaviorist utopias? |

|

![]()

Tuesday, 16 June: Class meeting cancelled due to weather-risks (Tropical Storm Bill).

Original schedule rolls forward one meeting at a time (i.e. Tuesday's assignment moves to Thursday; Thursday's assignment to Monday.)

Presenters may be reassigned. (Changes to be reviewed at Thursday 18 June meeting.)

Presenters: Let me know if date-changes conflict with your availability.

Rationale for cancelling class: Weather's unpredictable, but all the warnings are to "stay off the roads." Even if some students could make class, others would likely miss and fall behind.

Absence of a July 4th holiday this summer gave an extra class meeting, so this seemed like an acceptable way to use it.

The 7 July class for Looking Backward will now be our last day for Oryx and Crake.

![]()

|

Thursday, 18 June Readings: Anthem, chapters 1-4 Discussion starter: Lori Wheeler Web review: Jane Addams: instructor (Progressive Era > Roaring 20s > New Deal + Great Society) Model Assignment highlights (research posts): Instructor |

Agenda: research post assignment; Model Assignments; MLA bibliography (Modern Language Association); reference librarians Anthem discussion: Lori genre conventions of utopia / dystopia > origin stories: Web: Addams |

|

|

Herland: Further discussion? How explain, defend as feminist or women's utopia? 5.78 > Anthem: Background: As literary genre, Anthem is not a utopia but a dystopia, but genres remain co-dependent. Discussion Questions: 1. compare / contrast Anthem to utopian texts. How are utopias & dystopias co-dependent for identity? 2. What automatic appeals or "readability" do dystopian texts enjoy over utopian texts, at least for a modern or American audience? (e.g. romance narrative) 3. While Rand's status in the literary canon is controversial, Anthem offers some strong if limited literary appeals. How may we characterize Rand's style? What appeals to fundamentalist freemarket capitalism +- evangelicalism? 4. What do utopian texts scant or blur that Rand emphasizes and develops? What consciousness does she demonstrate of utopian texts and structures? (Obviously she despises them, but her text shows occasional knowledge of utopian forms.) 1.28 5. Resemblance to other early-mid 20c dystopias or satirical utopias like Brave New World, Nineteen Eighty-Four, Animal Farm, Lord of the Flies? What resemblances or differences relative to teen dystopias, zombie apocalypse, etc.? |

|

![]()

| First research post due weekend of 19-21 June |

|

![]()

|

Monday, 22 June Readings: Anthem (complete) Discussion starter: Joe Bernard Web review: Young Adult Dystopias: Lori Wheeler Web review: Ayn Rand biography, institutes, ideology: Jan Smith

|

Agenda: Web: Jan discussion: Joe Web: Lori

|

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. Conclusion to

Anthem: does it expose

some upsides to utopia?

3a. Continue discussion of Rand's

style and its potential appeals

(or demerits). Suggestions: biblical-scriptural,

mythical, superlatives / extremes?

|

|

![]()

|

Tuesday, 23 June Readings: begin Ecotopia pp. 1-17 (up to "Food, Sewage, & 'Stable States'") Discussion starter: Russell Lanier Web review: Celebration USA: Michaela Fox Instructor's Presentation: 60s-70s Utopian fictions, esp. Marge Piercy, Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) Standard features / conventions of utopian / dystopian literature > midterm |

Agenda: research posts review / midterm / assignments web: Michaela Ecotopia: Russ 60s-70s utopia |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. How does Ecotopia immediately connect to our other utopian texts as a representative of the genre? 2. How to define the literary genre of “utopias?” What conventions repeatedly appear? What audiences are involved or excluded? 3. What genres join with or branch from utopia? Examples: dystopia, ecotopia, Socratic dialogue, science fiction, fantasy, novel / romance, adventure / travel narrative, journalism, tract, propaganda, satire. Others? 4. In the entertainment / instruction balance, how well does Ecotopia work as entertaining fiction as opposed to didactic literature? |

|

![]()

|

Thursday, 25 June Readings: continue Ecotopia (through p. 59, up to "In Ecotopia's Big Woods") Discussion starter(s): Mel Hodgkins Web review: Suburbs as Utopia / Dystopia: Russ Lanier Model Assignment highlights (midterm essays): (instructor will do web highlights) |

Agenda: Assignments, midterm web: Russ Ecotopia discussion: Mel

|

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. Standard features / conventions of utopian / dystopian literature: Everyone responsible for identifying one utopian convention (or variation) in Ecotopia, or #2 below.

2. Re obj. 1 on hybrid novel / tract, how well does Ecotopia use both

genres? Compare to earlier utopian texts for character,

sexuality, narrative-dialogue mix. 3. How is Ecotopia "dated?"—i.e., an earnest but naive expression of 60s-70s consciousness? What remains impressive? What surprises? 4. Callenbach varies the utopian narrative by combining Weston's learning about Ecotopia with sexual learning or initiation. How convincing is this use of sexuality for narrative and social structure? Does it help characterization, or is it just embarrassing and hippie? 4a. How does Weston's sexual instruction / learning resemble that of the men in Herland? 5. Observe social mores in Ecotopia, esp. its "public" nature: compare utopias' reduction or transformation of private property and private family? |

|

![]()

|

Readings:

complete Ecotopia

Discussion starter(s): Joe

Bernard

Web review:

reviews, interviews re Margaret Atwood, Oryx

& Crake, Year of the Flood: Jessica Myers Instructor reviews:

Utopian Fiction &

Experimental Communities in North America / USA,

Adam Smith's

The Wealth of Nations;

USA founding documents, |

Agenda: assignments, midterm: conclude Ecotopia: Joe final exam preview preview Atwood: Jessica founding documents +- utopia |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. In the final episodes of Weston's initiation, can the Ecotopians' behavior be compared to that of a cult? What difference between a commune / intentional community and a cult? 2. How effective is the coordination of Weston's love story with Marissa and the narrative of his ideological initiation? 3. As visual description, the novel's best passages may be the competitive games as opportunity for aggression-expression, + mystical healing associated with highly sexualized society. Discuss.

5. Ecotopian literature: "Ecotopian novels . . . security, almost like 19c English novels; world is decent, satisfactory, sustaining despite some difficulties . . . . At first the stories seemed puzzlingly vapid to me. I couldn’t figure out why anybody would find them interesting . . . How come they didn't have that exciting nightmare quality? Some of them even have happy endings. . . . After a while, they seem more like life—okay to spend time with, reassuring. Come to think of it, Ecotopia itself is beginning to feel a good deal more reassuring: when I needed care, I was taken care of." |

|

![]()

| Tuesday, 30 June: midterm assignment (instructor holds office hours during class period; email midterm due by noon Wednesday, 1 July) |

![]()

|

Thursday, 2

July

Readings: begin

Oryx and Crake (chs. 1-2, through p. 33)

Presentation on Oryx and Crake as

speculative fiction and as part of

MaddAddam trilogy (Oryx and Crake,

2003; The Year of the Flood,

2009; MaddAddam,

2013): Hannah Wells Web review:

19th-Century American Utopias:

Eunice Renteria |

Agenda: Midterms status, assignments, schedule O & C: questions? presentation: Hannah Wells [break] Web review: Eunice final exam |

![]()

|

Readings: continue

Oryx and Crake (through ch. 6, p. 144) +

“In

Utopia”: Modern-day adventures in utopian living. interview of J. C.

Hallman, author of In Utopia, 15

August 2010 (The Big Sort

)

Discussion starter(s): Jessica

Myers (concentrate on obj. 1b? Other topics, questions welcome) Obj. 1b. What genres

join with or branch from utopia? Examples: dystopia,

ecotopia, Socratic dialogue,

science

fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy,

novel /

romance, adventure / travel narrative, journalism, tract,

propaganda, satire. Others? Web review:

Kibbutzim of Israel: Umaymah

Shahid

Instructor's Presentation:

African American dystopias / utopias

incl. Morrison's Paradise

|

Web: Umaymah begin discussion: Jessica break + evaluations continue discussion: Jessica? African American utopias / dystopias |

|

|

Discussion Questions for 6, 7 July: 1. Genre(s): As the novel opens, what genre or genres appear operative? (Obj. 1: speculative fiction, science fiction, utopia / dystopia, satire?) How does Oryx & Crake immediately indicate it is a novel and not merely another precise specimen of utopian fiction? As a novel, how much is any utopian or dystopian passage rendered ironical by the presence of differing passages or voices? (cf. Bakhtin on dialogic of novel)

2. Style: For a serious writer who is widely respected in the higher education curriculum, Atwood's prose style is surprisingly accessible or readable. How does her writing reconcile being intellectually challenging but fluent and compelling to a wider audience? If a partial answer is her novels' socio-political relevance, how does Atwood's writing avoid automatic categorization as ideology or propaganda? Consider literary features, e.g., intertextuality, allusion, metaphor, or the Bakhtinian dialogic.

3. Content: How does Atwood criticize corporate capitalism realistically instead of hysterically? (Too direct a criticism of the natural order marginalizes voice, + novel ironizes even criticism.) 4. Religion in fiction may appear less as a supreme voice than as one of many voices or worldviews whose interplay generates creation of a social world. How does religion (or the "sacrilege" of "playing God" through bio-engineering) appear in the novel, with what degree of authority? |

Rednecked Crake  Thicknee |

![]()

|

Readings: Oryx and Crake complete?

Presentation on Oryx and Crake as

speculative fiction and as part of

MaddAddam trilogy (Oryx and Crake,

2003; The Year of the Flood,

2009; MaddAddam,

2013): Hannah Wells

Instructor's Presentation:

Neal Stephenson's

Snow Crash

(1992); Dennis Danvers's Circuit of Heaven (1998);

Dave Eggers,

The Circle

(2013)

Standard features

/ conventions of utopian /

dystopian literature |

Agenda: midterms, research post, final exam updates Virtual Utopias discussion: Jessica Hannah: Year of the Flood, MaddAddam |

![]()

Thursday, 9 July: final exam (final exam and 2nd research post due by email before or by noon Saturday 11 July), or send either or both earlier.

No regular class meeting. Instructor holds office hours.

![]()

|

|

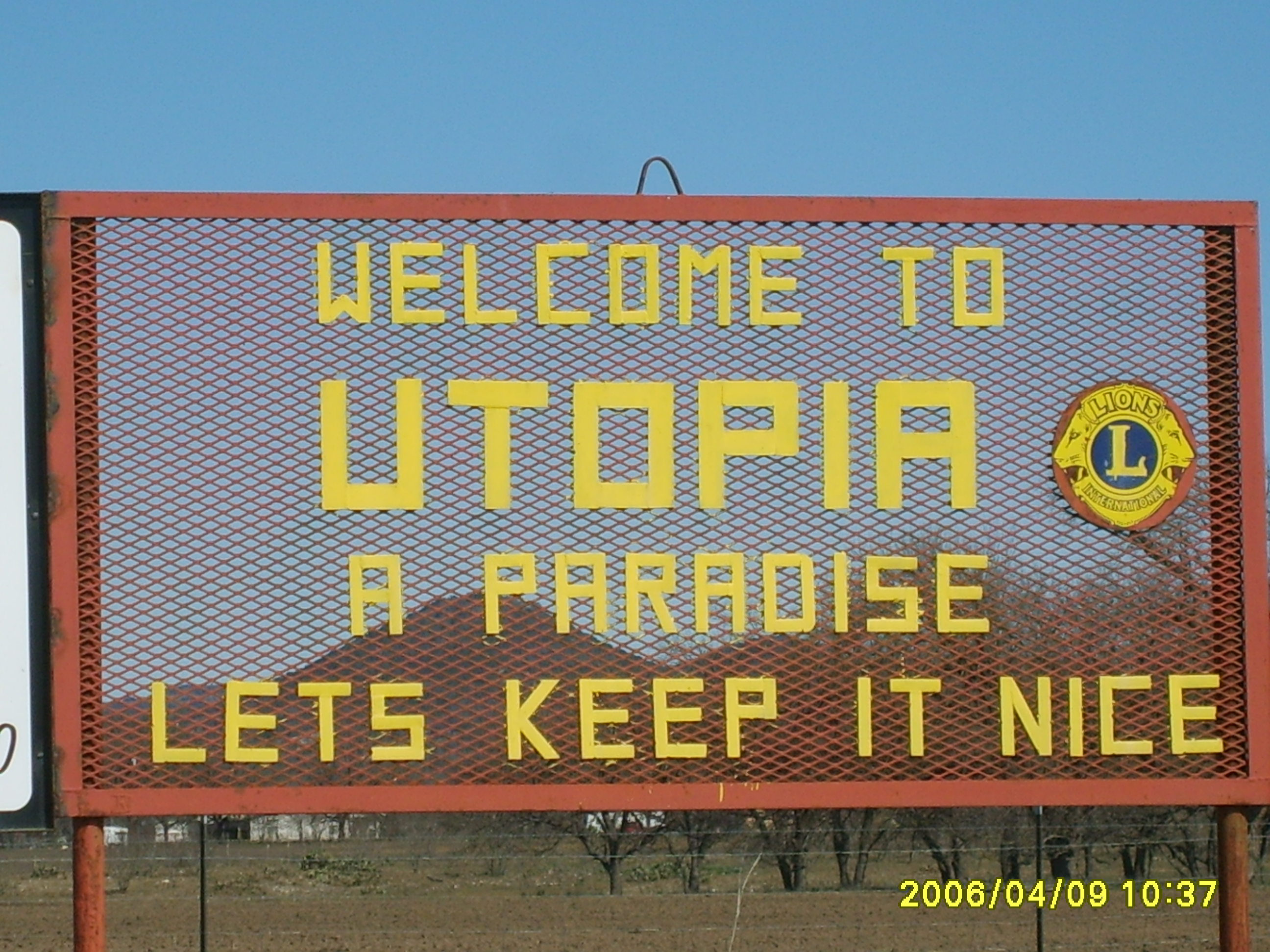

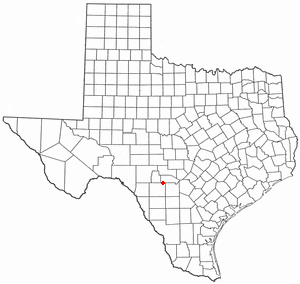

Utopia, Texas

(named in anticipation of a utopian project, cancelled after failure of La Reunion commune near Dallas)

![]()

Dr. White's publication & presentations on utopian, millennial literature

“A Utopia of `Spheres and Sympathies’: Science and Society in

"Cross-Cultural Apocalypse in the Contact Generation of Native

"`A Patterne and Copie to Imitate':

John Eliot's

"Brook Farm, Fourier, and the City of

"One Text, Three Worlds: A Narrative of Cosmological Transformation in

![]()

syllabus LITR 5733 Seminar in American Culture: Utopias (1995)

![]()

Presentations / web reviews for possible addition to syllabus:

Instructor's Presentation: Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia (1974)

Instructor's Presentation: Brook Farm (1840s) / Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Blithedale Romance (1852)

Instructor's Presentation: Lois Lowry, The Giver (1993)

![]()

Our texts within Western and American history:

|

text |

historical period |

historical tradition /

|

| More, Utopia (1516) | European Renaissance / Reformation; exploration & settlement of New World | America as site of Eden; communal Native America as precontact ecotopia |

| Bellamy, Looking Backward (1888) | late 19th century, "Gilded Age" | industrialization, urbanization, plutocracy of limited government, freemarket economics controlled by "Robber Barons" and "Captains of Industry"; gaps b/w rich and poor; high rates of immigration |

| Gilman, Herland (1915) | early 1900s, Progressive Era (associated with Pres. Theodore Roosevelt) | labor laws, scientific government and social work, woman's suffrage, environmental conservation and protection, industrial regulation; progressive income taxes |

| Rand, Anthem (1938) | mid-1900s, New Deal & Fair Deal (Franklin Roosevelt & Harry Truman) | peak of socialist-oriented government in USA; restricted immigration, government guarantees of social welfare (e. g., Social Security) + Cold War with negative totalitarian utopias of Soviet Union and Communist China |

| Callenbach, Ecotopia (1975) | 1960s-70s, liberal politics & social wealth (Civil Rights, Great Society safety net, war on poverty, hippies) | extension of New Deal to minorities; liberalization of immigration laws; peace movements; youth culture > adverse reaction by wealth & traditional values |

![]()

articles for potential inclusion on syllabus

Yves Charles Zarka, "The Meaning of Utopia" 2011

Michael Lind,

"Stop Pretending Cyberspace Exists," Salon.Com 12 Fe

Mike Konczal, "Thinking Utopian: How about a universal basic income?" Washington Post 11 May 2013.

notes for later offerings

suburbs as utopia / private-public identity

ETT Best of History Websites: Progressive Era

Jeet Heer, "The New Utopians." New Republic 9 Nov. 2015.

review of Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism. By Chris Jennings.

Mondragon, Mondragon Corporation