|

Isolated Desert Community Lives by Skinner's Precepts

|

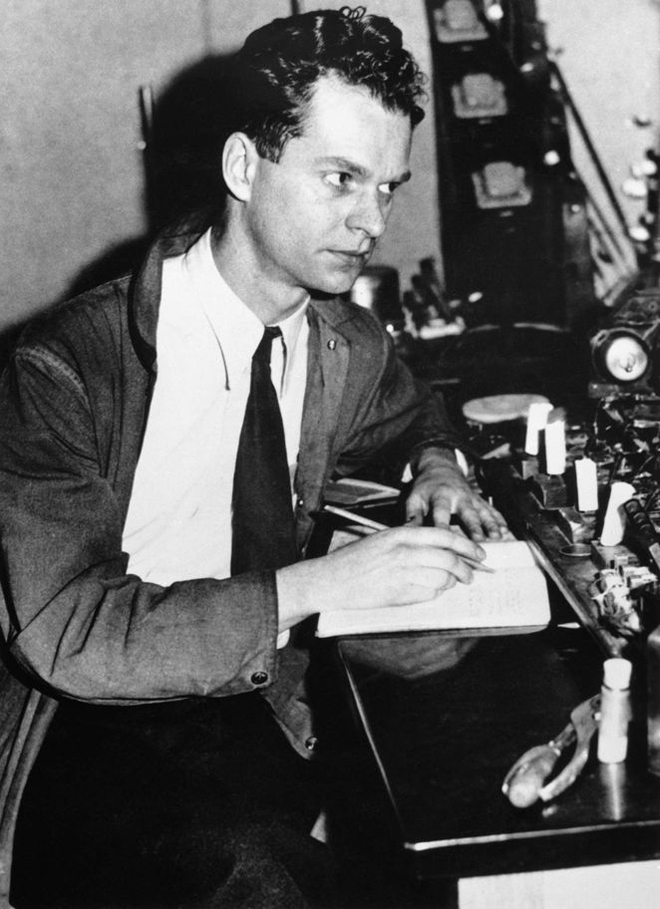

B.F. Skinner, 1904-1990 |

WHEN the psychologist B. F. Skinner wrote his utopian prescription ''Walden II''

some 40 years ago, he probably did not have in mind an isolated ranch in the

barren desert of northern Mexico. But 16 years after its founding, the Comunidad

los Horcones has come to represent the most sustained and complete effort to

apply to real life the behaviorist principles contained in Dr. Skinner's

novel-cum-textbook.

Situated some 175 miles due south of the Arizona border, this small,

self-supporting community sustains itself through farming and educational

programs for children from the city of Hermosillo, 40 miles away. But the

residents of Los Horcones, which means ''The Pillars'' in Spanish, also regard

themselves as scientists involved in a long-term research program and their

simple but comfortable rural outpost as a leading behaviorist laboratory.

Dr. Skinner's theory of behaviorism, which he developed in the 1930s, argues that people act as they do not out of free will, but because of rewards and punishments, or positive and negative reinforcements, meted out by culture and the envi-ronment. From this conviction arises the notion that societies can improve human behavior through reinforcement, much as laboratory animals can be conditioned to perform certain tasks.

Although the behaviorist approach dominated American psychology through the

1960s, in recent years it has lost considerable ground to the cognitive and

other schools of psychology. But the ongoing social experiment here, and the

large body of published data it has generated, constitutes for behaviorists

around the world proof that Dr. Skinner's theories have a solid intellectual

foundation and can be made to work.

''The central point is that we use the science of behaviorism and a more

objective understanding of human behavior to design a collective environment,''

said Juan Robinson, a former psychology student and teacher of autistic

children, one of the seven founding members of los Horcones. ''This community is

an application in its entirety of the analysis of the conduct of children and

adults, as well as the analysis of marriage and forms of social organization.''

Essential to the endeavor is the belief that human beings can be taught to

''build a society based on cooperation and not competition, on equality and not

discrimination, on sharing and not individual property, on pacifism and not

aggression,'' as the community's statement of principles puts it. But los

Horcones' 39 permanent residents, 28 adults and 11 children, also believe that

human behavior can only be redirected if conditions around people are changed to

support the desired behavior.

To achieve those goals, residents of los Horcones over the years have

collectively elaborated a detailed code of behavior that governs all major

aspects of community life. Children, for example, are guided by 24 classes of

behavioral objectives broken down into about 150 specific acts, while the code

for adults includes more than 30 classes of behavior.

To promote ideals of sharing and avoid undue attachment to possessions, for

instance, los Horcones residents make use of a large common clothing room, in

which shirts, pants and skirts belong to no one person and are available on a

first-come, first-served basis. Residents are encouraged to keep daily records

of their own actions and to analyze them, noting beneficial or unwanted

consequences that follow.

In addition, no individual wages are paid to residents, and all money earned by community enterprises is shared among members. The community votes as a whole on how to spend its earnings after discussing its needs and deciding on priorities.

Contact With Skinner

Despite their relative isolation, community members are in close touch with Dr.

Skinner through letters and an occasional videotape. At 85 years old, Dr.

Skinner says he is too old and frail to make the trip here to see his theories

in practice, but community members have visited him at Harvard and also

participated in a Harvard course on Walden II communities.

''They do a wonderful job with their children,'' Dr. Skinner said. ''They make

an effort not to punish children, and it shows. I've never seen a group of

kids

who so genuinely loved each other and were so cooperative with each other.''

With some pride, residents of los Horcones like to recall what happened when

someone introduced the children to the board game Monopoly. Instead of trying to

drive each other into bankruptcy, the young players offered to lend money to

each other so everyone could be wealthy.

The community's children do not live individually with their parents but in a

common house, where they are attended by adult members with training in infant

and child care and education. But each of the adults is expected to spend time

with the children and to help instill in them the equalitarian and cooperative

values on which the community is based.

Linda Armendariz, a founding member of the community, said: ''We try to treat

all of the children from birth as our own children, giving them the same

attention, care and tenderness as if we were their biological parents. In time,

the children come to treat all the adults as equal to their own parents.''

In the classroom, Dr. Skinner's emphasis on breaking complex topics into small,

manageable concepts, each of which is taught methodically so that the student

gets the reinforcement of mastering an idea before moving on to the next, is

followed even though Dr. Skinner's ''teaching machines'' are not used.

When a visitor sat in briefly on a pre-kindergarten lesson, children as young as 3 demonstrated an ability to read simple sentences, selected at random from teaching materials.

The 'Skinner Box'

Although the community does its best to follow Dr. Skinner's principles, it does

not use one of the tools that is most closely identified with the father of

behaviorism: the ''Skinner box.'' The box is actually a temperature-controlled

crib with Plexiglas walls that is equipped with a microphone and speaker so the

baby inside can communicate with parents. The reasons for not using such a

self-contained environment, community members say, are practical rather than

philosophical.

''It's not that we don't believe in the Skinner box,'' Mr. Robinson said. ''We

recognize that children suffer many aggressions from birth on. But it is much

more difficult to control heat than cold. We believe that children do better

where they are physically comfortable, and the temperatures around here can get

as high as 120 degrees.''

Founded in October 1973, los Horcones at first consisted of six adults and a

child. Several of the original members had studied psychology or education at

the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City and had become

interested in behaviorism. Over the years, residents have included Norberto

Corella, a prominent member of the Mexican Congress, as well as uneducated

peasants and tradesmen.

Until 1981, the community was situated on the outskirts of Hermosillo. It moved to its present location here, 250 acres equipped with electricity and water but without telephone service, after an industrial park sprang up around the original site and some robberies occurred.

Similar Communities

Since the 1960's, other Walden II communities have been founded in Virginia,

Kansas, Michigan and Canada. But Dr. Skinner, who complains that many of his

concepts were distorted during the hippie era by ''the Maharishi and whatnot,''

says los Horcones comes closest to the idea of the ''engineered utopia'' that he

put forth in ''Walden II,'' which has sold more than two million copies and is

used in college psychology courses all over the world.

''Nobody is quite as systematic about it as they are,'' he said in a telephone

interview from his home in Cambridge, Mass. ''They are intelligent and

dedicated, with daily sessions to go over the principles of behavioral analysis.

Instead of weaving hammocks, they use their skills as behavioral engineers with

children, and that's the way to do it.''

Almost every aspect of community life here is studied and quantified. The

findings are regularly published in a variety of specialized journals of

psychology and sociology in the United States, Latin American and Europe,

providing the grist for many an academic debate.

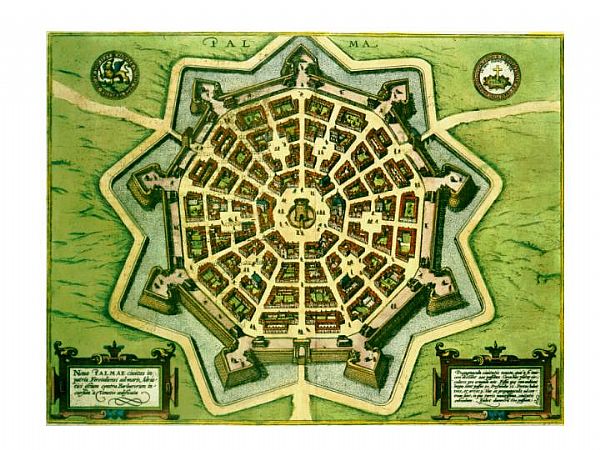

Campanella's

City of the Sun