LITR 5439 Literary & Historical Utopias

|

Brave New World 1931 by Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) |

|

Opening question: Are students in seminar acquainted with this text? If so, under what conditions did you read it? What outstanding memories or issues? Discussion context?

Welcome to interrupt presentation with information, observations, or questions.

Reasons to know text & author (cultural literacy):

Title from speech by Miranda in Shakespeare's The Tempest (1610-11), act 5, scene 1: "O brave new world / That has such creatures in't."

Brave New World ranks #5 on Modern Library's list of 100 greatest English-language novels of the 20th Century (1998). (Modern Library's status: publisher of "modern classics," esp. in paperback with great mid-twentieth-century influence; absorbed into Vintage imprint in 1960 but re-established in 1990s.)

With George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 (1953), and William Golding's Lord of the Flies (1954), Brave New World was a fixture in the American canon of dystopian-collective fiction of the later Twentieth Century (partly supplanted recently by Hunger Games & other YA Dystopias). Often taught in high schools, now maybe more frequently in Advanced Placement.

[Subtext for literary studies and curriculum: Cold War / Baby Boomer favorites (incl. the controversial Huckleberry Finn and Heart of Darkness) have continued to dominate secondary and introductory-college Literature courses until recently.]

Huxley was grandson of Thomas H. Huxley (1825-95), celebrated naturalist, partisan and friend of Charles Darwin. (Huxley as a defender of scientific evolution was nicknamed "Darwin's Bulldog" and famously coined the term "agnostic" in 1869 to limit discussions of science and religion to what is empirically knowable.)

Huxley's mother, Julia Arnold Huxley, was sister to Mary Augusta Ward (1851-1920), novelist known professionally as Mrs. Humphrey Ward. Mrs. Ward's novels, some of which were best-sellers and the subject of extended critical discussion, often represented Victorian religious issues. Mrs. Ward also participated in settlement movements; cf. Jane Adams (1860-1935) and Hull House.

Huxley's mother was also the niece of Victorian poet and literary-cultural critic Matthew Arnold (1822-88; Culture and Anarchy [1867-69] and the famous poem "Dover Beach" (1867), which the protagonist Montag recites in Ray Bradbury's 1953 dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451.

|

|

|

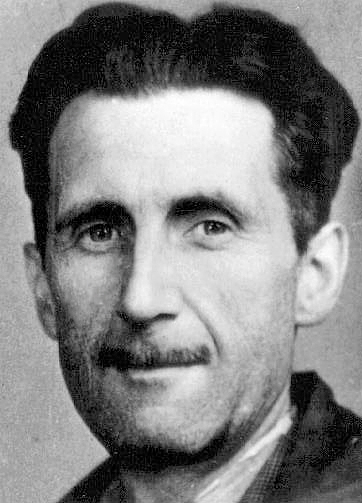

Dialogue / exchange between Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) & Brave New World (1931) and George Orwell (1903-1950) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

Huxley taught Orwell in French at Eton College, England.

Orwell reviewed Brave New World in 1940, nearly a decade before publishing Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949).

Orwell sent Huxley a review copy of Nineteen Eighty-Four to Huxley, in response to which Huxley wrote

Both Huxley and Orwell were influenced by the Russian novel We (1921, 1924) by Evgeny Zamyatin.

|

|

|

|

Other reasons to know Aldous Huxley Appears on cover of Rolling Stone's #1 all-time record album, The Beatles's Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967). 1954 The Doors of Perception, nonfiction book describing hallucinatory mental state after taking mescaline. The book's title, taken from William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), inspired the name of the 60s rock band The Doors. 1958 Brave New World Revisited: nonfiction assessing how the world is moving more quickly toward the novel's vision than he had ancitipated three decades earlier. 1962 Island as utopian text:

Huxley dies same day as President John Kennedy and C.S. Lewis (22 Nov. 1963) |

Science fiction / Utopian elements in Brave New World

Historical change since 1931 renders anachronistic some of the text's scientific systems, but overall the models remain familiar enough—and described efficiently enough—that overall vision of the future seems plausible if not somewhat inevitable. (Potentially a pre-digital perspective.)

Application of early 20th-century industrial processes to human reproduction and divisions of labor.

Application of psychological conditioning to transformations of social behavior + divisions of labor.

Social trends: increasing population and rising standards of living result in overwhelming of high culture by mass popular culture enhanced by electronic media.

![]()

Brave New World as fiction w/ plot / narrative conflicts and summary

Brave New World full online text

Character index for Brave New World

Setting: London in the Year of Our Ford A.F. 632 (AD 2540 acc. to Gregorian calendar) ("Ford" refers to Henry Ford, whose maximization of assembly-line industry serves as a semi-divine revelation of social efficiency and productivity.)

Settings also feature visits to a Pueblo Indian reservation in Southwestern USA (now part of World State).

As with much utopian fiction, Brave New World's characterization is superficial to formulaic. The central couple--Henry Foster and Polly Trotsky--are, respectively, a frustrated intellectual and an intellectually limited but sexually attractive hatchery line worker who, as their relationship develops, become disenchanted with the polyamorous sexuality of the society

The major plot conflict, however, is between the values of "the Savage" or "John Savage," an Anglo young man born through an off-the-grid liaison on the Indian reservation and self-educated by reading Shakespeare and other high classics, and representatives of the new society, artificially reproduced, educated by conditioning, and entertained by low mass culture entertainments known as "feelies" or distracted by "soma," a euphoria-inducing drug with limited after-effects compared to alcohol.

As with many world-scale science fictions, the plot also depends on a family drama to connect the major characters. The Savage turns out to be the grown, unacknowledged son of the Director of Hatcheries, conceived twenty years earlier on a previous vacation trip to the Pueblo Reservation.

![]()

Reasons to admire text (formal and historical):

Suspension of genre / reception between satirical dystopia and plausible inevitability.

Huxley wrote Brave New World in response to the utopian-dystopian literary tradition, then most prominently championed by H.G. Wells, with Jules Verne the "father of science fiction." Wells wrote both utopian novels (A Modern Utopia, 1905 and Men Like Gods, 1923) and a dystopian novel (When the Sleeper Wakes,1899, rewritten as The Sleeper Awakes, 1910). In a letter to Mrs. Arthur Goldsmith, Huxley wrote, "Wells's Men Like Gods annoyed me to the point of planning a parody, but when I started writing I found the idea of a negative Utopia so interesting that I forgot about Wells and launched into Brave New World."

![]()

Limits to text's new-millennium appreciation or application

London-centered, though visits to Southwestern USA

Hypnopedia's dependence on hypnotism as powerful psychological transformative agent seems dated, but if one dismisses the trance-associations of hypnotism, techniques of suggestion and socio-psychological manipulation have flourished in mass communications and marketing.

![]()

Notes from Aldous Huxley, Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited. NY: HarperPerennial / Modern Classics,

Foreword (2004) by Christopher Hitchens

vii Huxley dies same day as President John Kennedy and C.S. Lewis (22 Nov. 1963)

sex divorced from procreation

reproduction cloning ehtics

fetal stem-cells in medicine

public life = spectacle and entertainment

viii photo on Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) [see below]

The Doors named for The Doors of Perception < William Blake

"Brave new world" < Miranda in Shakespeare's Tempest; cf. "Catch-22," "Nineteen Eighty-Four": virtual hieiroglyphics which almost automatically summon a universe of images and associations"

Huxley taught George Orwell [French] at Eton + classmate?

ix George Orwell review Brave New World 1940

[WW2 and Cold War made 1984's vision more pressing]

x combination of annihilating war and subsequent obliteration of cultural and historical memory

x-xi "[Orwell] was writing about the forbidding, part-alien experience of Nazism and Stalinism, whereas Huxley was locating disgust and menace in the very things—the new toys of materialism, from cars to contraceptives--that were becoming everyday pursuits."

xi Huxley . . . often tended to condescend to the readers, as much of the dialogue in Brave New World also tends to do. It is didactic and pedagogic and faintly superior . . . .

grandfather T. H. Huxley, celebrated naturalist, partisan and friend of Charles Darwin . . . coined term "agnostic"

maternal uncle: Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy

xii eugenics popular in Victorian . . . Social Darwinism

xiii Mustapha Mond cf. Mustapha Kemal (Ataturk)

xix fictional characters as puppets to illustrate his points

lack of characterization

deficiencies: Nature, Religion, Literature > chemical, mechanical, sexual comforts

xv a reactionary modernist cf. Evelyn Waugh

xvi-xvii letter to George Orwell after Nineteen Eighty-Four [see below]

xvii Nineteen Eighty-Four = scarcity; Brave New World: abundance

xix Brave New World Revisited LSD . . . another aspect of soma

friend of Timothy Leary

xx A map of the world that does not show Utopia, said Oscar Wilde, is not worth glancing at.

![]()

[author's] Preface [for second edition of Brave New World, 1947] (online copy at http://www.wealthandwant.com/auth/Huxley.html)

8 Brave New World contains no reference to nuclear fission. . . . The oversight may not be excusable; but at least it can be easily explained. The theme of Brave New World is not the advancement of science as such; it is the advancement of science as it affects human individuals.

It is only by means of the sciences of life that the quality of life can be radically changed.

8-9 This really revolutionary revolution is to be achieved, not in the external world, but in the souls and flesh of human beings. Living as he did in a revolutionary period, the Marquis de Sade very naturally made use of this theory of revolutions in order to rationalize his peculiar brand of insanity. Robespierre had achieved the most superficial kind of revolution, the political. Going a little deeper, Babeuf had attempted the economic revolution. Sade regarded himself as the apostle of the truly revolutionary revolution, beyond mere politics and economics -- the revolution in individual men, women and children, whose bodies were henceforward to become the common sexual property of all and whose minds were to be purged of all the natural decencies, all the laboriously acquired inhibitions of traditional civilization.

11 . . . in an age of advanced technology, inefficiency is the sin against the Holy Ghost. A really efficient totalitarian state would be one in which the all-powerful executive of political bosses and their army of managers control a population of slaves who do not have to be coerced, because they love their servitude. To make them love it is the task assigned . . . .

12 The love of servitude cannot be established except as the result of a deep, personal revolution in human minds and bodies. To bring about that revolution we require, among others, the following discoveries and inventions.

- First, a greatly improved technique of suggestion -- through infant conditioning and, later, with the aid of drugs . . . .

- Second, a fully developed science of human differences, enabling government managers to assign any given individual to his or her proper place in the social and economic hierarchy. . . .

- Third . . . a substitute for alcohol and the other narcotics, something at once less harmful and more pleasure-giving than gin or heroin.

- And fourth (but this would be a long-term project, which it would take generations of totalitarian control to bring to a successful conclusion), a foolproof system of eugenics, designed to standardize the human product and so to facilitate the task of the managers. . . . Meanwhile the other characteristic features of that happier and more stable world—the equivalents of soma and hypnopaedia and the scientific caste system—are probably not more than three or four generations away. Nor does the sexual promiscuity of Brave New World seem so very distant. There are already certain American cities in which the number of divorces is equal to the number of marriages. . . . As political and economic freedom diminishes, sexual freedom tends compensatingly to increase. And the dictator . . . will do well to encourage that freedom. In conjunction with the freedom to daydream under the influence of dope and movies and the radio, it will help to reconcile his subjects to the servitude which is their fate.

13 . . . unless we choose to decentralize and to use applied science, not as the end to which human beings are to be made the means, but as the means to producing a race of free individuals . . . .

![]()

Notes

Chapter 1

15 setting: CENTRAL LONDON HATCHERY AND CONDITIONING CENTRE

World state motto: COMMUNITY, IDENTITY, STABILITY

16 Alpha students [intellectual conditioned; ironically, real name for advanced students in local CCISD schools]

incubators . . . week's supply of ova [utopia's / dystopia's inclination to plan reproduction to maximize human quality and reduce sexual conflicts]

18 modern fertilizing process

Gammas, Delts, and Epsilons > Bokanosky's Process

one egg, embryo > 96

series of arrests of development

18 a prodigious improvement . . . on nature

19 principle of mass production at last applied to biology

20 Bokonaovsky Group

21 Social Predestination Room

Eighty-eight cubic meters of card index [once again, sf fails to anticipate electronic information technology]

![]()

Wrightwood. Cal.

21 October, 1949

Dear Mr. Orwell,

It was very kind of you to

tell your publishers to send me a copy of your book. It arrived as I was in the

midst of a piece of work that required much reading and consulting of

references; and since poor sight makes it necessary for me to ration my reading,

I had to wait a long time before being able to embark on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Agreeing with all that the

critics have written of it, I need not tell you, yet once more, how fine and how

profoundly important the book is. May I speak instead of the thing with which

the book deals—the ultimate revolution? The first hints of a philosophy of the

ultimate revolution — the revolution which lies beyond politics and economics,

and which aims at total subversion of the individual's psychology and physiology—are to be found in the Marquis de Sade, who regarded himself as the

continuator, the consummator, of Robespierre and Babeuf. The philosophy of the

ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to

its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it. Whether in actual

fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful.

My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful

ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will

resemble those which I described in Brave New World. I have had occasion

recently to look into the history of animal magnetism and hypnotism, and have

been greatly struck by the way in which, for a hundred and fifty years, the

world has refused to take serious cognizance of the discoveries of Mesmer,

Braid, Esdaile, and the rest.

Partly because of the

prevailing materialism and partly because of prevailing respectability,

nineteenth-century philosophers and men of science were not willing to

investigate the odder facts of psychology for practical men, such as

politicians, soldiers and policemen, to apply in the field of government. Thanks

to the voluntary ignorance of our fathers, the advent of the ultimate revolution

was delayed for five or six generations. Another lucky accident was Freud's

inability to hypnotize successfully and his consequent disparagement of

hypnotism. This delayed the general application of hypnotism to psychiatry for

at least forty years. But now psycho-analysis is being combined with hypnosis;

and hypnosis has been made easy and indefinitely extensible through the use of

barbiturates, which induce a hypnoid and suggestible state in even the most

recalcitrant subjects.

Within the next generation I believe that the world's

rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more

efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the

lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into

loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience. In other

words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate

into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined

in Brave New World. The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need

for increased efficiency. Meanwhile, of course, there may be a large scale

biological and atomic war — in which case we shall have nightmares of other and

scarcely imaginable kinds.

Thank you once again for the

book.

Yours sincerely,

Aldous Huxley

Source: Letters of Aldoux Huxley

reprinted in http://www.lettersofnote.com/2012/03/1984-v-brave-new-world.html

Wilson, Edward

O. On Human

Nature. Harvard UP, 1978, 2004.

Chapter 9. Hope

195 . . . the seemingly fatal deterioration of the myths

of traditional religion and its secular equivalents . . . a loss of moral

consensus, a greater sense of helplessness about the human condition, and a

shrinking of concern back toward the self and the immediate future.

198 Truly exceptional individuals, weak or strong, are,

by definition, to be found at the extremes of statistical curves, and the

hereditary substrate of their traits come together in rare combinations that

arise from random processes in the formation of new sex cells and the fusion of

sex cells to create new organisms. Since each individual produced by the sexual

process contains a unique set of genes, very exceptional combinations of genes

are unlikely to appear twice even within the same family. So if genius is to any

extent hereditary, it winks on and off through the gene pool in a way that would

be difficult to measure or predict. Like Sisyphus rolling his boulder up and

over to the top of the hill only to have it tumble down again, the human gene

pool creates hereditary genius in many ways in many places only to have it come

apart the next generation. The genes of the Sisyphean combinations are probably

spread throughout populations. For this reason alone, we are justified in

considering the preservation of the entire gene pool as a continent primary

value until such time as an almost unimaginably greater knowledge of human

heredity provides us with the option of a democratically contrived eugenics.

208 Then mankind will face the third and perhaps final

spiritual dilemma. Human genetics is now growing quickly along with all other

branches of science. In time, much knowledge concerning the genetic foundation

of social behavior will accumulate, and techniques may become available for

altering gene complexes by molecular engineering and rapid selection through

cloning. At the very least, slow evolutionary change will be feasible through

conventional eugenics. The human species can change its own nature. What will it

choose? Will it remain the same, teetering on a jerrybuilt foundation of partly

obsolete Ice-Age adaptations? Or will it press on toward still higher

intelligence and creativity, accompanied by a greater—or lesser—capacity for

emotional response? New patterns of sociality could be installed in bits and

pieces. It might be possible to imitate genetically the more nearly perfect

nuclear family of the white handed gibbon or the harmonious sisterhoods of the

honeybees. But we are talking here about the very essence of humanity. Perhaps

there is something already present in our nature that will prevent us from every

making such changes. In any case, and fortunately, this third dilemma belongs to

later generations.

![]()

[from Chapter 3—dialog b/w two women workers turns into something like poetic collage]

"Perfect!" cried Fanny

enthusiastically. She could never resist Lenina's charm for long. "And what a

perfectly sweet Malthusian belt!"

"Accompanied by a campaign against the

Past; by the closing of museums, the blowing up of historical monuments (luckily

most of them had already been destroyed during the Nine Years' War); by the

suppression of all books published before A.F. 150."

"I simply must get

one like it," said Fanny.

"There were some things called the pyramids,

for example."

"My old black-patent bandolier ..."

"And a man

called Shakespeare. You've never heard of them of course."

'It's an

absolute disgrace—that bandolier of mine."

'Such are the advantages of a

really scientific education."

'The more stitches the less riches; the

more stitches the less ..."

'The introduction of Our Ford's first

T-Model ..."

'I've had it nearly three months."

'Chosen as the

opening date of the new era."

'Ending is better than mending; ending is

better ..."

'There was a thing, as I've said before, called

Christianity."

'Ending is better than mending."

'The ethics and

philosophy of under-consumption ..."

'I love new clothes, I love new

clothes, I love ..."

'So essential when there was under-production; but

in an age of machines and the fixation of nitrogen-positively a crime against

society."

'Henry Foster gave it me."

All crosses had their tops

cut and became T's. There was also a thing called God."

It's real

morocco-surrogate."

thanks to

http://harlanonhuxley.tripod.com/id11.html