|

Craig White's Literature Courses Utopian Motives |

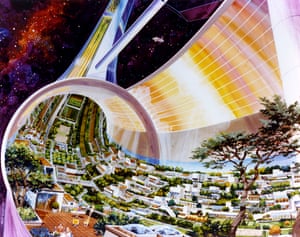

Wow! Let's colonize space! |

In normal capitalist society, incentive to work rises from the profit motive or self-interest involving competition for theoretically scarce resources or commodities.

In a collective, cooperative, socialist or communist society, however, such individualistic motives are repressed or redirected, while others are promoted instead.

Examples:

competition b/w teams or collective units:

Thomas More, Utopia (1516): [2.4c] . . . there lie gardens behind all their houses. . . . They cultivate their gardens with great care, so that they have both vines, fruits, herbs, and flowers in them; and all is so well ordered and so finely kept that I never saw gardens anywhere that were both so fruitful and so beautiful as theirs. And this humour of ordering their gardens so well is not only kept up by the pleasure they find in it, but also by an emulation beween the inhabitants of the several streets, who vie with each other. And there is, indeed, nothing belonging to the whole town that is both more useful and more pleasant.

![]()

honor, pageantry (badges), emulation

Looking Backward 7.6: Our young men are very greedy of honor . . . .

9.47:

[9.47]

"Does it then really seem to you," answered my companion, "that human

nature is insensible to any motives save fear of want and love of

luxury, that you should expect security and equality of livelihood to

leave them without possible incentives to effort?

. . . Not higher wages, but honor and

the hope of men's gratitude, patriotism and the inspiration of duty,

were the motives which they

[19c leaders] set before their soldiers when it was a question of dying for the

nation, and never was there an age of the world when those motives did

not call out what is best and noblest in men. And not only this, but

when you come to analyze the love of money which was the general impulse

to effort in your day, you find that the dread of want and desire of

luxury was but one of several motives which the pursuit of money

represented; the others, and with many the more influential, being

desire of power, of social position, and reputation for ability and

success. So you see that though we have abolished poverty and the fear

of it, and inordinate luxury with the hope of it, we have not touched

the greater part of the motives which underlay the love of money in

former times, or any of those which prompted the supremer sorts of

effort. The coarser motives,

which no longer move us, have been replaced by higher motives wholly

unknown to the mere wage earners of your age. Now that industry of

whatever sort is no longer self-service, but service of the nation,

patriotism, passion for humanity, impel the worker as in your day they

did the soldier. The army of industry is an

army, not alone by virtue of

its perfect organization, but by reason also of the

ardor of self-devotion which animates its members.

The results of each regrading, giving the standing

of every man in his industry, are gazetted

[published]

in the public prints [newspapers, journals], and those who have won

promotion since the last regrading

receive the nation's thanks

and are publicly invested with the

badge

[pageantry & honor]

of their new rank."

[12.4]

"What may this

badge be?" I asked.

[12.5]

"Every industry has its emblematic device," replied Dr. Leete, "and this,

in the shape of

a metallic badge

so small that you might not see it unless you knew where to look, is

all the insignia which the men of the army wear, except where public

convenience demands a distinctive uniform. This badge is the same in

form for all grades of industry, but while the badge of the third grade

is iron, that of the second grade is silver, and that of the first is

gilt.

[12.6]

"Apart from

the grand incentive to endeavor afforded by the fact that the high

places in the nation are open only to the highest class men, and that

rank in the army constitutes the

only mode of social distinction for the vast majority who are not

aspirants in art, literature, and the professions, various

incitements of a minor, but perhaps equally effective, sort are provided

in the form of special privileges and immunities in the way of

discipline, which the superior class men enjoy. These, while intended to

be as little as possible invidious to the less successful, have the

effect of keeping constantly before every man's mind

the great

desirability of attaining the grade next above his own.

[emulation]

Pageantry as spectacle

Herland

[9.46] . . .

The drama of the country was—to our taste—rather flat. You see, they lacked the

sex motive and, with it, jealousy. They had no interplay

of warring nations, no aristocracy and its ambitions, no wealth and poverty

opposition.

[9.47] . . . I'll go

on about the drama now.

[9.48] They had their own kind. There was a most impressive array of pageantry, of processions, a sort of grand ritual, with their arts and their religion broadly blended. The very babies joined in it. To see one of their great annual festivals, with the massed and marching stateliness of those great mothers, the young women brave and noble, beautiful and strong; and then the children, taking part as naturally as ours would frolic round a Christmas tree—it was overpowering in the impression of joyous, triumphant life.

Anthem

1.32 a play is shown upon the stage, with two great choruses

![]()

Extended family, esp. parents (or mothers') love for children > concern for future improvement

Herland

[5.80] The power of mother-love, that maternal instinct we so highly laud, was theirs of course, raised to its highest power; and a sister-love . . .

[6.49]

"Here we have Human Motherhood—in

full working use," she went on. "Nothing else except

the literal sisterhood of our origin,

and the far higher and deeper union of our social growth.

[6.50]

"The children in

this country are the one center and focus of all our thoughts. Every step of

our advance is always considered in its effect on them—on the race.

You see, we are MOTHERS," she

repeated, as if in that she had said it all.

.jpg/1920px-Kim_Il_Sung_Birthday_Celebrations_April_15,_2014_(14056865633).jpg)

Kim Il-Sung birthday, North Korea

.jpg/1280px-Mass_Dance_on_National_Day_(10104371223).jpg)

North Korea, Liberation Day festival

May Day, Soviet Union