|

Craig White's Literature Courses Critical Sources

Introduction to

as

Subject / Audience Identification |

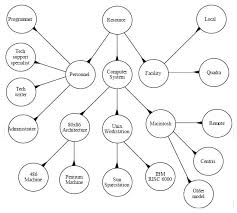

"Genres" are interrelated classifications with lists of recognizable attributes as in chart above on another subject |

Brief definition: genre = "A particular style or category of works of art; esp. a type of literary work characterized by a particular form, style, or purpose." (Oxford English Dictionary, 1.b.; eytmology: French genre or "kind")

Caution(s): This page offers more structure for "genre" than speakers normally use. Keep in mind these warnings:

![]() "There are no pure genres": nearly all works of art and

literature contain multiple dimensions or elements of other genres; e.g. "romantic comedy";

"cyber-thriller"; "gothic romance"

"There are no pure genres": nearly all works of art and

literature contain multiple dimensions or elements of other genres; e.g. "romantic comedy";

"cyber-thriller"; "gothic romance"

![]() Genres are not final answers but discussion points or starters

for criticism and evaluation.

Beware passing a point of diminishing returns!

Genres are not final answers but discussion points or starters

for criticism and evaluation.

Beware passing a point of diminishing returns!

![]() Genre is not a box in which to put a work of art but a yardstick to measure

it by.

Genre is not a box in which to put a work of art but a yardstick to measure

it by.

"Genre" is a flexible and adaptable term or concept. At its simplest genre is what you're discussing when you ask,

![]() "What kind of book is that?"

or

"What kind of movie do you want to see?" or "If I

watch go to this show with you, what am I getting into?"

"What kind of book is that?"

or

"What kind of movie do you want to see?" or "If I

watch go to this show with you, what am I getting into?"

Questions about genre may return a number of answers. "What kind of book?" may be "a novel" or "a detective novel." The answer to “what kind of movie?” might be “a comedy,” a romantic comedy," or “an action film,” or an "action-thriller." All of these are genres, more or less, and any work of literature may involve not one but several of these terms.

These familiar classifications amount to a "contract with the audience": a genre or any work of literature will offer standard features or fulfill expectations, norms, or "conventions" of style and tone. If the preview or trailer for a movie makes it look like a comedy, the audience trusts the movie will make us laugh. A reader purchasing a detective novel expects a mysterious crime (and a solution).

Most readers, critics, and students use “genre” in casual or unconscious ways, and some may resent genre analysis for making a box or cage in which to imprison a work of art—a coffin in which to bury it! If we regard genre more like a yardstick than a box, the terms helps identify and evaluate similarities and differences between similar texts, or distinguish something new and innovative from mere duplication (as in "potboilers" or "formula fiction").

For purposes of critical thinking, the study of genres is classification, taxonomy, or categorization, a process by which ideas or objects are recognized, differentiated, and evaluated.

![]()

Classifying classes or genres of literature

Basic definition from Oxford English Dictionary: genre 1.a. Kind; sort; style. b. spec. A particular style or category of works of art; esp. a type of literary work characterized by a particular form, style, or purpose. [A related term in modern use is "generic drug," meaning a type or category of drug similar to a larger family of drugs.]

In literature, genre may be classified in three broad, non-exclusive categories:

1. Subject / Audience Identification: The content, subject, "special interest" or "audience appeal" of a text, such as "a crime story" or a "teenage movie."2. Form: the form in which the text appears; specifically, the types and numbers of “voices” that present the genre

3. Narrative: the type of story or plot told or acted: comedy, romance, satire, tragedy, or combinations.Every specimen or text of literature can be classified not by just one of these categories but by all three. (Examples at bottom of screen.)

In keeping with the fluidity of genre, these categories are also "non-exclusive" of teach other. They often overlap—especially categories 1 & 3. That is, subject-genre of a text will often determine its narrative-genre. For instance, the subject genre of "comedy" usually entails the comedy narrative genre.

In contrast, the subject genre of romance as "love story" is more specific and limiting than the romance narrative, a quest or journey that may involve love, revenge, justice, honor, or rescuing a lost child.

However, subject-genres are more numerous and their names may change with fashion. For instance, comedy may multiply to "dumb and dumber comedy," "low comedy," "comedy of manners," dark comedy, situation comedy, sketch comedy, improvidsational comedy, etc.—though all will share (to some degree) the narrative of comedy.

![]()

1. Subject / Audience Identification refers to the content, subject matter, "special interest" or "audience appeal" of a text or genre, such as "a crime story," a "teen movie," an "adult film," or "a children's show."

This classification is the most obvious or popular use of "genre." When people ask, "What kind of book are you reading?" or "What kind of movie do you want to see?", what they really want to know is, "What is it about?" or “What are you interested in?”—to which one answers, for instance, "A thriller." Audiences outside literary studies often take representational and narrative genres for granted or remain unconscious of such distinctions.

“Special interest” or “audience identification” makes the connection between the subject of a genre and its audience. For instance, if we answer the movie question with “A chick-flick” or “a guy movie,” we provide information about the audience that also suggests the content of the movie. Often the audience identifies with the content or characters.

For examples of Subject / Audience Identification genres, see List of Genres, many of which fit this class of genre.

But examples are easy to come up with just by thinking of the kinds of books you like to read or the movies or tv shows you like to watch: "crime stories," boy-meets-girl, situation comedy or sitcom, science fiction, zombie flicks, slasher films, coming-of-age dramas, and on and on.

“Subject genre” concerns less the “form” of the genre (as in formal and narrative genres) than some content that is duplicated from one example to another, for example:

-

science fiction (Star Wars, Star Trek) techno-thrillers (Tom Clancy, Hunt for Red October, etc.)

-

police drama historical fiction, historical romance monster movies

-

gothic western novel / movie weepers or 3-hanky movies Tarzan stories / Tarzan movies

-

spy novels / spy movies / A James Bond movie

"Subject genre" is the simplest, most obvious way to classify literature and art, but its terms may serve more for convenient reference than intensive analysis (except for fans of this or that subject).

The second two approaches (“formal” and “narrative”) often have more academic prestige because their recurrent but variable patterns work across various texts regardless of subject or content.

![]()

2. “Formal genre”: number and types and number of voices + relation to the audience, or the "form" in which the text appears. There are three types and examples of formal genre, though a single text or performance may shift from one formal genre to another:

![]() 2a. Narrator or “Single Voice,”

in which one speaker or voice speaks directly to the audience.

Examples: lyric poems, songs, sermons, lectures, stand-up comic

monologues, news reports, or any other situation where a speaker directly

addresses an audience, camera, or microphone.

2a. Narrator or “Single Voice,”

in which one speaker or voice speaks directly to the audience.

Examples: lyric poems, songs, sermons, lectures, stand-up comic

monologues, news reports, or any other situation where a speaker directly

addresses an audience, camera, or microphone.

Examples of Single-Voice Narrator (e.g., speech, newscast, lyric poem)

Dr. Martin Luther King, I Have a Dream (1963)

Walt Whitman, "There Was a Child Went Forth"

Emily Dickinson, "A Narrow Fellow in the Grass"

![]() 2b. Drama or

Dialogue, in which

two or more characters speak directly with each other, which the audience

overhears.

Examples: most drama or plays,

most movies, most fictional television shows such as sit-coms or police dramas.

2b. Drama or

Dialogue, in which

two or more characters speak directly with each other, which the audience

overhears.

Examples: most drama or plays,

most movies, most fictional television shows such as sit-coms or police dramas.

Jerry Seinfeld stand-up (single-voice) > Seinfeld situation comedy

![]() 2c. Narrator + Dialogue, in which

two or more characters speak with each other while a narrator speaks directly to

the audience.

Examples:

fiction,

novels; the

epic (e.g. Iliad and

Odyssey, others); “film noir” movies or children's movies with voice-over narration; TV shows like The Wonder Years where an older narrator speaks to the audience

while a younger self speaks with other characters.

2c. Narrator + Dialogue, in which

two or more characters speak with each other while a narrator speaks directly to

the audience.

Examples:

fiction,

novels; the

epic (e.g. Iliad and

Odyssey, others); “film noir” movies or children's movies with voice-over narration; TV shows like The Wonder Years where an older narrator speaks to the audience

while a younger self speaks with other characters.

Wonder Years (1988-93) situation comedy featuring voice-over

Out of the Past (1947 film noir)

Fiction: F. Scott Fitzgerald, "Winter Dreams" (1923)

Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (1719)

Critical sources for formal genre: "Form" is both an abstract idea and an actual phenomenon. If you imagine people talking, what form does your imagination take? Is someone speaking directly to you, or do you see and hear people talking among themselves as though you're not there? Or some combination?

The standard critical source for "formal genre" is Plato, The Republic. c. 373 BCE: "[A story] may be either simple narration, or imitation, or a union of the two."

The standard critical source for "formal genre" is Plato, The Republic. c. 373 BCE: "[A story] may be either simple narration, or imitation, or a union of the two."

![]() "simple narration" refers to

2a above: a "narrator" or "single-voiced" representation.

(Plato's example is the "ode" or lyric

"simple narration" refers to

2a above: a "narrator" or "single-voiced" representation.

(Plato's example is the "ode" or lyric

![]() "imitation" or

mimesis here refers to 2b above: "drama or

dialogue," which is how humans appear when they're talking among themselves

"imitation" or

mimesis here refers to 2b above: "drama or

dialogue," which is how humans appear when they're talking among themselves

![]() "a union

of the two" refers to 2c "narrator +

dialogue," a form Plato would

have known via epic poetry.

"a union

of the two" refers to 2c "narrator +

dialogue," a form Plato would

have known via epic poetry.

These options develop from theories of representation, imitation, or mimesis: "Art imitates reality," or "art represents nature." That is, literature (or art) is not nature or reality itself but something humans make that resembles, interprets, or shapes reality or nature. In this usage, form therefore refers to the way art appears or presents itself as an imitation of reality.

![]()

3. “Narrative genre” refers to the type of story or plot that a work of literature tells or enacts. The source for such literary criticism is Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (1957), according to which there are four basic story lines:

Though distinct, these narratives often work in combination—for instance, romantic comedy. Or an episode of one narrative genre may appear in another, like the comic gravedigger’s scene in the tragedy of Hamlet.

Tragedy. The story begins with a problem that is significant to society, its leaders, or its representatives. The problem may rise from a temptation or error that human beings recognize within themselves, such as greed, pride, or self-righteousness.

The problem is intimate and integral to human identity; it is not "objectified" to a villain or outside force, as in romance. Good and bad are not split, but mixed.

Action consists of an attempt to discover the truth about the problem, to follow or trace or absorb its consequences, to restore justice (even at cost to oneself), or to regain moral control of the situation.

The tragic narrative concludes with resolution of the problem and restoration of justice, often accompanied by the death, banishment, or quieting of the tragic hero.

Comedy. This story-line often begins with a problem or a mistake (as in mistaken identity), but the problem is less significant than tragedy. The problem may involve a recognizable social situation, but unlike tragedy, the problem does not intimately threaten or shake the audience, the state, or the larger world. (Compared to tragedy, comedy doesn't have consequences. When someone falls down, they get back up.

The problem or conflict often takes the form of mistaken or false identity: one person being taken for another, disguises, cross-dressing, dressing up or down, mixed signals. The action consists of characters trying to resolve the conflict or live up to the demands of the false identity, or of other characters trying to reconcile the “new identity” with the “old identity.”

Comedy ends with the problem overcome or the disguise abandoned. Usually the problem was simply “a misunderstanding” rather than a tragic error. The concluding action of a comedy is easy to identify. Characters join in marriage, song, dance, or a party, demonstrating a restoration of unity. (TV "situation comedies" like Friends or How I Met Your Mother end with the characters re-uniting in a living room or some other common space.)

Occasionally, as in slapstick or farce, comic endings are “circular” with the beginning: the comic characters simply “run away,” supposedly to continue the comic action elsewhere, as in the conclusion of some sketches by the Three Stooges or Laurel and Hardy.

In “dark comedy,” the conclusion is sometimes one of exhaustion, as in The War of the Roses or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.

Romance.

Protagonists are motivated by desire for fulfillment or a vision of transcendent grace; cf. desire and loss.

Satire. The word “satire” appropriately comes from Greek for “mixed-dish,” as its story-line tends to be extremely episodic and opportunistic, and the genre typically involves elements of other genres including comedy, humor, wit, and fantasy.

-

The satirized topic may be humanity or society in general, or particular classes or pastimes [e.g., Christmas, the Prom, freshman year], but typically the genre satirizes politics, sex, and religion. Since laughter is pleasing and diverting and makes one feel superior, satire may enjoy more liberty than other genres in treating such sensitive subjects.

-

As another disarming device, the narrator or protagonist of satire may be a "naif"--an innocent person (usually young and likeable) who appears to lack any pre-existing attitudes toward right or wrong in what s/he observes, and so makes the object of satire appear more preposterous. Examples: Candide in Voltaire's Candide, Huck in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Austin Powers, etc. Compare deadpan style.

-

As a "mixed dish," the satiric narrative may depend for its narrative integrity on the audience’s knowledge of the original story being satirized. Gulliver's Travels (1726) may begin as a satire not only of European societies but of The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1718), published only 8 years earlier.

-

In (fairly) recent instances, the Hot Shots movies may appear to be simply an unconnected series of goofy scenes unless you’ve seen Top Gun and other warrior-hero movies, in which case you know that episodes from the satire spoof or parody episodes from the original films. Young Frankenstein similarly depends on a familiarity with the original Frankenstein or at least with the cliches of old-time horror movies.

-

More recent examples:

-

Scary Movie series spoofs I Saw What you Did Last Summer, Blair Witch Project, Scream (itself a satire), etc.

-

Not Another Teen Movie (2001) parodies Pretty in Pink, She's All That, 10 Things I Hate About You, + references to American Pie, The Breakfast Club, Footloose, The Karate Kid, and other examples of the "Teen Movie" genre, with stock character types like "the Pretty Ugly Girl," "the Popular Jock," "the Cocky Blonde Guy," "the Nasty Cheerleader," and "the Token Black Guy."

-

Structurally, the satirical narrative will end somewhat like the original narrative, but, in terms of tone, the seriousness or pretensions of the original narrative will be deflated.

As a single-voiced example, an impersonator depends on his audience’s pre-knowledge of a celebrity’s mannerisms and foibles. (E.g., when an actor on Saturday Night Live imitates a U.S. President or candidate, the audience recognizes the candidate's pre-existing quirks and finds pleasure in the quality of their mimesis.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

As exhausting as this handout may be, it’s not exhaustive! “Genre” remains a capacious, slippery, and evolving term and concept. The purpose of these classifications is more to exercise critical thinking than to provide final answers.

For those considering graduate school, some problems inherent in “genre studies”

“Genre courses” like “Tragedy,” “Comedy,” “Introduction to Fiction (or Poetry or Drama),” or “Film as Literature” tend to be popular mainstays in college curricula, but genre scholarship as such has a lackluster reputation. Why?

-

Genres may be regarded as elementary knowledge.

-

Genres impinge on so many other subjects that findings may evade reduction or specification.

-

Any attempt at finality in describing a genre may ascribe an artificial purity or purity to an evolving entity.

![]()

Every work of literature involves at least one subject genre, one formal genre, & one narrative genre.

*A stand-up comedian’s monologue is “single-voiced” in representation and “comic” in terms of narrative (by attempting to conclude on a big audience-uniting laugh.)

- Subject / Audience: dating, politics, romance, domestic, social classes—topics may vary with audience or venue.

- Form: single-voiced (one person talking to audience, w/ variations like enactments of dialogues or exchanges with audience)

- Narrative: “comic” through impersonations (false identity), put-downs (deflation, restoration of order), conclusion on big audience-uniting laugh.

*The novel The Scarlet Letter

- Subject: social and ethical issues; human relations between individuals and their community; Puritanism and the American past, etc.

- Form: narrator (voice describing setting, characters, and action) + two or more characters in dialogue (Hester, Dimmesdale, and Pearl in conversation with each other).

- Narrative: romance (as when Hester transcends her complications by becoming an “angel” at the end) shaded by tragedy (as in Dimmesdale’s fall through his own faults and errors).