|

|

Homepage / Syllabus Spring 2016 companion courses: LITR 5831 Colonial-Postcolonial; LITR 4370 Tragedy

|

|

|

Meeting Days Monday 7-9:50pm Bayou 2235 Instructor: Craig White Office: Bayou 2529-8 Office Hours: 4-7 Mondays, 5-7 Tuesdays & by appointment Phone: 281 283 3380 Email: whitec@uhcl.edu

|

midterm & research plan

(20-30%)

research plan and options

(15-25 Feb.)

final exam

(25-35%) student presentations & participation |

Course Texts

|

Tragedies from Classical Greece |

Criticism & Theory |

Plays & Novels from 20th-Century Africa |

|

Aeschylus, The Oresteia (Agamemnon complete + selections from Libation Bearers & Eumenides) (458 BCE) Sophocles, Oedipus the King (429 BCE) Sophocles, Antigone (c. 442 BCE) Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus (406, 401 BCE)

|

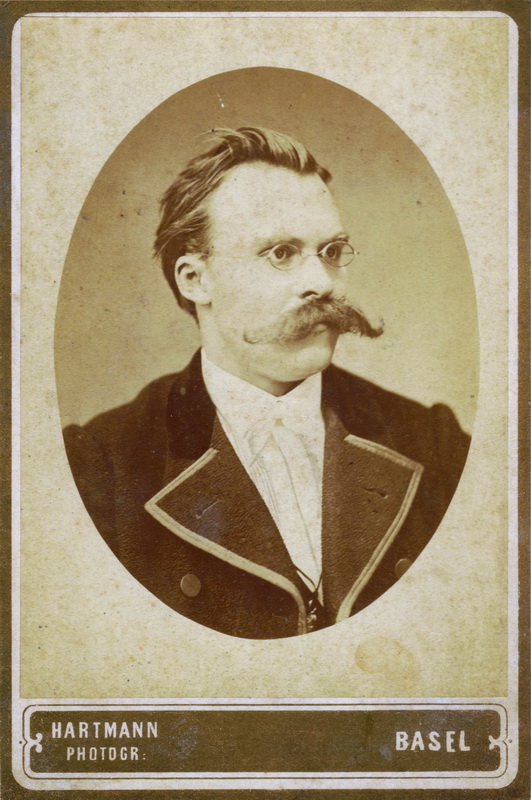

Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Shaun Whiteside (Penguin Classics; ISBN 978-0-14-043339-5)

|

Wole Soyinka,

Death & the King’s Horseman

(1975) Chinua Achebe,

Things Fall Apart

(1957) Buchi Emecheta, The Rape of Shavi (1983) (George Braziller, 978-0807611180) Ngugi wa Thiong’o,

A Grain of Wheat

(1967) |

Handouts (concerning Tragedy; links for African literature and culture appear in schedule)

Course

Premises, Objectives, & Terms

(continued below reading schedule)

Purposes:

1. To read together great ancient literature of Western Civilization with great modern literature from Africa, the continent whose relation with Western Civilization is most problematic or “other.”

2. To mediate the

prestige of classical Western literature with the competing claims of excellence

and representation of multicultural literature.

3. To extend or limit visions of humanity and genre across cultures—are people all the same, or do history and culture make us different?

4. What do we gain as readers by bringing two such distinct literary traditions into dialogue?

Premises:

1. Tragedy is regarded as the

greatest literary genre of

Western Literature, and its birth occurring during the "golden age" of Classical

Athens and the birth of Western Civilization..

2. Western Civilization typically excludes Africa.

(Exceptions: European colonialism of Africa + New World Slavery / African

Diaspora)

3. 20th-century

Postcolonial African literature includes texts with tragic narratives.

4. Africa as birthplace of humanity is also

where many modern crises play out (overpopulation, tropical diseases, genocide,

Moslem and Christian fundamentalism, resource extraction and environmental

degradation, postcolonial

states).

5. What questions and possibilities do these conditions raise? What does it mean to study Tragedy and Africa together?

![]() Universal (simple) answer:

All people are basically the same, so tragedy is a universal genre. (immediately

gratifying but limiting)

Universal (simple) answer:

All people are basically the same, so tragedy is a universal genre. (immediately

gratifying but limiting)

![]() Historical (complicated) answer:

Tragedy in Western Civilization accompanies expansive periods of modern empire;

African tragedy rises in response to contact with Western Civilization,

modernity, and / or development as modern nation-states.

Historical (complicated) answer:

Tragedy in Western Civilization accompanies expansive periods of modern empire;

African tragedy rises in response to contact with Western Civilization,

modernity, and / or development as modern nation-states.

![]() Formal answer:

Tragedy or the tragic narrative may

constitute the modern human condition or

its expression.

Formal answer:

Tragedy or the tragic narrative may

constitute the modern human condition or

its expression.

![]() Forbidden answer:

“People like tragedy because they like seeing other people

worse off than they are.” (Confuses “tragedy”

with spectacle.)

Forbidden answer:

“People like tragedy because they like seeing other people

worse off than they are.” (Confuses “tragedy”

with spectacle.)

Be careful with

common, popular, or sentimental uses of “tragedy,” as in "What a tragedy!"

Non-academic speech applies the term to unfortunate events or untimely ends to

life-stories, especially when the end is undeserved. Literary Tragedy is more

complicated and less sentimental—no one is perfectly good, and no one escapes

blame—but like the sentimental usage it addresses questions of justice and

morality.

(course

objectives continue below reading schedule)

![]()

Reading & Presentation Schedule, spring 2016

|

Monday, 25 January: Course introduction Readings: Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, p. 14; notes + visit Birth of Tragedy Glossary + Apolline / Dionysiac; Discussion: instructor preview Oresteia trilogy |

Agenda: syllabus, organization, assignments presentations (student preferences) midterm, rationale for course [break] next week's assignments Aristotle's Poetics--spectacle begin Birth of Tragedy |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. What do we already know about classical Greek tragedy (or later tragedy)? 1a. Aristotle? Nietzsche? 2. What do we know (or think we know) about Africa? Colonialis and Postcolonialism? 2a. What knowledge of African literature or authors? Preview

default

discussion questions for every class: 1.

How or why is a text classified as a Tragedy or not? 2.

Do texts reflect universal or cultural values (i.e., Western

Civilization or African? Modern or Traditional?) 3.

What aspects of the text elude classification as Tragedy? What other

terms or categories are applicable? 4.

What is surprising about Tragedy? (As greatest genre, tragedy must

evolve) 5.

How does Tragedy complicate questions of crime and justice? 6.

How may Tragedy and Africa meet? |

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) |

![]()

|

Monday, 1 February: The Oresteia Readings: The Oresteia Trilogy of Aeschylus (only surviving trilogy of Greek tragedies): Agamemnon (complete); The Libation Bearers (excerpts); The Eumenides (excerpts) discussion leader: instructor Aristotle's Poetics: parts I, IV: instructor

Video presentation: Caryn Livingston Oakland production of Agamemnon (masks) humorous amateur silent production of Death of Agamemnon (YouTube) The Death of Agamemnon (Texas State U.)

Bacchae Presentation One (lines 1-72): instructor |

Agenda: genres + tragic narrative; business, assignments, presentation preferences history + universality? (intro video) Classical Greek Poets & Philosophers > Aeschylus (video); Aristotle's Poetics 4c, 13b, 13c, 14c discussion leader assignment video: Caryn [break] videos: RFK & MLK (l. 212) Euripides, Bacchae #5 Apolline / Dionysiac Oresteia as trilogy (compare O'Neill, Mourning Becomes Electra) assignments: mask videos |

|

|

Discussion

questions: 2. Everyone can agree that Agamemnon sacrificing his daughter Iphigenia is horrible, but in the spirit of tragedy, how is it that he's not just a villain or a bad guy as in romance? 3. What dramatic power in Cassandra's appearance & speech at end of Agamemnon? 4. Uses or repression of spectacle? 5. How may Agamemnon or The Oresteia exemplify Nietzsche's Apolline & Dionysiac?

Oresteia as a trilogy:

6. Libation Bearers: How does Electra model the "Electra Complex" relative to the Oedipal Complex? 7. Euminides: How "tragic" is the ending of The Eumenides & the Oresteia trilogy? Compare to end of comedy in narrative genres. Can it all still be a tragedy if everyone doesn't die at the end? 8. What does the trilogy achieve in terms of civilization? If the Furies or Vengeful Ones are changed into Eumenides or Kindly Ones, what progress has been made? |

Orestes slaying Clytaemnestra |

![]()

|

Monday, 8 February: Death & the King's Horseman Readings:

videos: D&KH video 1; dance; Soyinka interview (6:30); Fela Kuti (38) |

Agenda: presentations; introduction to D&KH discussion questions tragic narrative + comedy & romance Trojan Women at Obsidian Theater Aristotle: mimesis + learning videos

|

|

|

Discussion Questions for 8 & 15 February: 1. Using Aristotle's Poetics and text-to-text comparison with Oresteia, How may Death and the King's Horseman be a tragedy or not? What advantages and disadvantages to identifying a modern African drama with a Classical Greek tragedy? Consider: family, learning, masks, mixed characters (Jane, Chief's son); spectacle; tragic narrative; setting (market v. palace / urban center)? 1b. Compare to Nietzsche's Birth of Tragedy, esp. Apolline & Dionysiac?

default

discussion questions: 1.

How or why is a text classified as a Tragedy or not? 2.

Do texts reflect universal or cultural values (i.e., Western

Civilization or African? Modern or Traditional?) 3.

What aspects of the text elude classification as Tragedy? What other

terms or categories are applicable? 4.

What is surprising about Tragedy? (As greatest genre, tragedy must

evolve) 5.

How does Tragedy complicate questions of crime and justice? 6.

How may Tragedy and Africa meet? |

Egungun masquerade dance garment  Yoruba Divination Tray |

|

Monday, 15 February: Death & the King's Horseman Readings:

Bacchae Presentation Two (lines 73-332): instructor |

Agenda: midterm Trojan Women Shared & Unique Elements & Themes: Tragedy & Africa discussion: Jeanette Bacchae

|

![]()

Monday, 22 February: (early) midterm exam: no regular class meeting; instructor keeps office hours 4-10; email exams due by weekend of 26-28 February.

![]()

|

Monday, 29 February: Oedipus Rex: begin Theban Cycle Readings: Sophocles, Oedipus the King (429 BCE) The Oedipus Complex, including selections from Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams Video presentation: (2+ scenes from following links): Oedipus Rex: the Short, Short Version; Opening of 1984 TV movie of Oedipus the King, part one; Oedipus Rex (1957 film); 1968 film of Oedipus the King Video presentation: Niki Bippen

|

Agenda: Model Assignments; schedule NYT article on tragedies; Oresteia & O'Neill's Mourning Becomes Electra Questions re Obsidian Theater's The Trojan Women by Euripides Birth of Tragedy: Hanna Discussion questions video Aristotle, Poetics & Oedipus Oedipal conflict and Hamlet

|

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. Oedipus the King is often proclaimed the greatest classical tragedy, but no one considers it friendly or easy to like, and in fact it's rarely performed. What are the obstacles to enjoying this play? What types of pleasure are possible? Why is it so difficult to identify or sympathize with Oedipus as a tragic hero? 2. If Oedipus the King isn't "friendly," the Oedipus Complex is also a challenging subject. Why do literary texts and literary studies keep representing and discussing such a repellent story or subject? How viable (or obsolete) is the Oedipus Conflict for discussing literature, particularly tragedy? How does the concept survive in popular and academic culture, even as an object of satire? Identify impulses to dismiss and ignore it, or grounds for its persistence and validity? 2a. How much may the Oedipal Conflict apply to previous course readings? Aeschylus's Libation Bearers is sometimes cited for the female-correspondent Electra Complex, but more particularly how may the Oedipal Conflict appear in Death and the King's Horseman, esp. the relation of Elesin and Olunde? (though the mother figure is conspicuously absent except perhaps in the figure of Iyaloja, whose own son's marriage plans are disrupted by Elesin's attraction to the son's fiancee). 3. Oedipus as a character is often discussed in terms of fate vs. free will, and the "tragic flaw" or hamartia. How to characterize Oedipus's tragic flaw and how it relates to the mixed characterization of tragedy? 4. How much is spectacle repressed or indulged in the conclusions to Oedipus the King and Hamlet? 5. "Detective stories" remain a popular variation on the romance narrative in which a conflict is introduced or social order is disturbed, evil is projected on a villain, and social order is restored with the villain's punishment. (examples?) In what ways is Oedipus the King like a detective story? In what ways essential to tragedy does it differ?

default

discussion questions: 2.

Do texts reflect universal or cultural values (i.e., Western

Civilization or African? Modern or Traditional?) 3.

What aspects of the text elude classification as Tragedy? What other

terms or categories are applicable? 5.

How does Tragedy complicate questions of crime and justice? |

Oedipus w/ Antigone & Ismene |

![]()

|

Readings:

begin Chinua Achebe,

Things Fall Apart

(1957)

Bacchae

Presentation

Three (lines 333-539): Aristotle's Poetics: parts XIV, XV, XVIII; Discussion: instructor

|

Agenda: midterms, research schedule, presentations final course text? Bacchae: Heather Aristotle's Poetics and Oedipus the King [break] discussion: Jeanette |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. Things Fall Apart is taught in high schools and colleges across the United States. If someone has read only one novel written by an African, that novel is usually Things Fall Apart. How many of you read it before? For which courses, with what lessons, themes, emphases? 1a. Why or how does this novel succeed for so many diverse readers? If your answer is "universal," what are the attractions and dangers of "universal themes?" How can the dialogue or dialogic process manage those conflicts? 1b. How may the Oedipal Complex appear in Things Fall Apart, particularly in the relationship of Okonkwo and his son Nwoye? Is the Oedipal Complex unique to the western culture of modernization, or common to the west and Africa? 2. What about African people qualifies as “traditional?" What attractions and risks to tradition? e.g. What ranges to women's status in traditional societies? Traditional culture as gendered culture? 13, 23, 64, 109-10 Added observation and question: In the second half of Things Fall Apart, the novel's narrative pace and the immediacy or intensity of the reader's involvement seems to slacken, so that in past seminars students often concentrate on the opening third and the final chapter (Okonkwo's suicide) while largely ignoring the bulk of the novel’s second half (, and I myself don’t remember those parts nearly as well. Could our attention be more focused on the violence that punctuates the plot? (While we're at it, how do Achebe's representations of violence fit with tragedy's management of spectacle?)

default

discussion questions for every class: 1.

How or why is a text classified as a Tragedy or not? 2.

Do texts reflect universal or cultural values (i.e., Western

Civilization or African? Modern or Traditional?) 3.

What aspects of the text elude classification as Tragedy? What other

terms or categories are applicable? 5.

How does Tragedy complicate questions of crime and justice? 6.

How may Tragedy and Africa meet? |

|

|

(14 March spring break: no class meeting) > Readings:

complete Chinua Achebe,

Things Fall Apart

(1957) Bacchae Presentation Four (lines 540-814): instructor Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, Chapter 8, pp. 40-45 notes + Birth of Tragedy Glossary; Discussion: Caryn Livingston |

Agenda: schedule, assignments, question re final text Bacchae part 4 Birth of Tragedy: Caryn [break] Things discussion: Heather Objective 1 caveat; universal humanism & cultural-historical respect

|

![]()

First Research Post due 21-26 March (not required from students writing research essays or research journals)

![]()

|

Readings:

Bacchae Presentation Five (lines 814-1126): Hanna Mak Video presentation: Antigone (1984 TV movie), part 1; part 2; part 3; part 4; part 5; part 6; part 7; part 8; part 9; part 10; part 11 Presenter: Nikki Bippen |

Agenda: assignments, research schedule, final text discussion and video: Niki [break] Bacchae: Hanna Birth of Tragedy |

|

|

Discussion Questions: 1. A generation ago, Oedipus the King was the standard "classical tragedy" read in secondary schools. Today the tragedy of choice is Antigone, which is more popular to teach as classical tragedy in schools today—why? What are its appeals compared to Oedipus the King? How does Antigone feel more popular and appear more modern? (tragedy modernizes)

2. Only men wrote Greek tragedies, but women often appear as central characters. What conflicts or responsibilities do women represent that make their lives appropriate subjects for tragedy? In Antigone, for instance, how does the title character's acting out expose larger problems in Thebes and its leadership? 3. Who is the play's tragic hero? Antigone or Creon? How much does Creon's tragic flaw appear as a crisis of masculinity? Compare Creon to Okonkwo or Pilkings as tragic hero. How much may the tragic flaw be described as a simple failure of humanity? 4. How comical (or potentially comic) are the Guard's repeated appearances? ll. 256 ff., 366, 385, 432-450 |

Antigone accounting to the Chorus |

![]()

|

Readings:

Buchi Emecheta, The

Rape of Shavi (1983), through chapter 10 (p.88). Nietzsche, Birth of Tragedy, Chapters 9-10, pp. 45-54 notes + Birth of Tragedy Glossary; Discussion: Jeanette Smith Instructor presentation: Aeschylus's Seven Against Thebes |

Agenda: research, assignments, additional questions re Shavi? presentations? discussion: Hanna [break] Birth of Tragedy: Jeanette instructor presentation |

|

|

Discussion Questions:

1.

Rape of Shavi can be identified with a number of genres:

science fiction,

utopian fiction,

allegory,

melodrama, and more.

How may its narrative be classified as a

tragedy or not? How much does

the presence of

other genres support or conflict with a reading of the

Shavi as

Tragedy? 2. Dramatic tragedies often feature women in central roles but are written almost exclusively by men. Tragic narratives do appear in women's fiction—e.g. Toni Morrison, George Eliot, Emily Bronte. How does woman's authorship inflect tragic narrative and characterization in these and other texts but especially Rape of Shavi? 3. How may The Rape of Shavi exemplify post-colonial fiction, particularly in its moral and political characterizations of the colonizers and colonized? How do the two cultures exemplify modern and traditional ways? May the shift from tradition to modernity be associated with the appearance of tragedy in emergent empires or nations? 4. How may Patayon, Shoshovi, and Asogba exemplify the Oedipal Complex? How may the Oedipal Conflict mediate the shift from tradition to modernity? 5. Who are potential tragic heroes of the novel, with what tragic flaws? Consider Asogba, Flip? May the novel's discussions whether the "other" is human be associated with the tragic flaw? 6. Evaluate Emecheta's style. How much does it resemble Achebe's in its apparent naivete or flat affect? How much may this apparent naivete or artlessness be an artful stratagem?

Default questions: Do texts reflect universal or cultural values (i.e., Western

Civilization or African? Modern or Traditional?) |

|

|

Readings: Buchi Emecheta, The Rape of Shavi (1983) , complete Bacchae Presentation Six (lines 1126-1431): Caryn Livingston

|

Agenda: 7xThebes (greaves, sacrifice); Looking at Antigone review Birth of Tragedy: Heather Bacchae: Caryn Shavi discussion |

![]()

Research Essays, Research Journals, or 2nd Research Posts due 12-16 April.

![]()

|

Monday, 18 April: Oedipus at Colonus (Meeting Canceled—Inclement Weather) Readings: Sophocles, Oedipus at Colonus (406, 401 BCE) Video presentation: scene(s) from Gospel at Colonus; presenter: Heather Minette Schutmaat |

Agenda: research schedule, preview final exam next class discuss Oedipus at Colonus Gospel at Colonus: Heather assignments |

|

|

Discussion Questions: Oedipus at Colonus: The Furies are back! (These spirits of revenge pursued Orestes in the Oresteia. Here, the grove where Oedipus & Antigone rest is sacred to Furies, who would naturally be scandalized by Oedipus's crimes.) 1. Compare the chorus's and audience's potential catharsis of "pity and fear" for Oedipus to our reactions to the same character in Oedipus the King. Since modern audiences typically have difficulty identifying with Oedipus as King, how may our attitudes to him change in this play? 2. Oedipus acts helpless, but how helpless is he really, and how much is he controlling the action? How convincing are his speeches justifying his past sins? Evidence of tragic flaw? 2a. Continuing #2, what about Oedipus's character is revealed by his cursing of Polyneices? Why is the scene so powerful and meaningful? Compare to Bible's parable of the Prodigal Son? (Potential contrast of Abrahamic and Classical Greek-Roman ethics) 2b. Since Antigone is Oedipus's true child, compare her character in Oedipus at Colonus to her character in Antigone. 3. How does Oedipus's death resemble the conclusion of a romance as transcendence? (narrative genres) 3a. Compare conclusion to conclusion of the Oresteia trilogy in The Eumenides? 4. Discuss spectacle in Oedipus at Colonus's finale or elsewhere in play? What advantages to showing or not showing rescues, divine actions, etc.? 5. Not to press comparisons to diminishing returns, but how might Oedipus's resolution appear Christ-like or compatible with the Christ story? (This potential analogy is partly encouraged by the translator's use of biblical language.) 6. Formal question: How do the rhymes and meters of the century-old translation of Oedipus at Colonus affect our reading of the play and our potential sense of its presentation (as poetry, song, dance) to an ancient Greek audience? |

Oedipus repudiating Polyneices |

![]()

|

Monday, 25 April: A Grain of Wheat Readings: Ngugi wa Thiong’o, A Grain of Wheat (1967); app. half-way, through ch. 7, p. 121 Text guide: A Grain of Wheat; Kenya Bacchae Presentation Seven (lines 1431-1776): Hanna Mak Instructor's presentation: review of V.S. Naipaul, A Bend in the River |

Agenda: final exam preview 2016 < 1916 the Easter Rising, Ireland; Yeats, "Easter 1916" review Oedipus at Colonus: instructor Bacchae: Hanna [break] begin Grain of Wheat Derek Walcott, "A Far Cry from Africa" Naipaul, Bend in River |

|

|

default

discussion questions:

1.

How or why may this text be classified as a Tragedy or not? 2.

Do tragedies reflect universal or cultural values? (i.e., Western

Civilization or African? Modern or Traditional?) 3.

What aspects of the text elude classification as Tragedy? What other

terms or categories are applicable? 4.

How does Tragedy complicate questions of crime and justice? 5.

How may Tragedy and Africa meet?

7. Compare the Rung'ei Market to the market in Death and the King's Horseman, the Greek theater and its settings for tragedy settings, the agora of Greek public life, and the field and stage for the Uhuru celebrations. (New York Review of Books) How may "staging" affect the content or effect of a tragedy?—that is, do tragedies require a central stage or ground where all characters may meet, where the domains of public and private also converge, and where spectacle may be expressed or repressed? 8. Discussion of question #1 above sometimes mentioned that a text "feels like a tragedy," sometimes specified as an ominous tone or atmosphere and a sense of inevitable doom plus or minus suspense. How may this atmosphere, tone, or tension be present in Grain of Wheat? 8a. How may the quality of characterization in Grain of Wheat immediately strike a reader as tragic? 9. How may the conclusion of Grain of Wheat and our other tragic texts represent irony, and how may irony, which is popularly associated with diminution or cynicism, be associated with the greatness of tragedy? |

|

|

Monday, 2 May: A Grain of Wheat Readings:

Ngugi wa Thiong’o,

A Grain of Wheat

(1967)

|

Agenda: final exam Gospel at Colonus: Heather [break + evaluations] discuss Grain of Wheat

|

![]()

Monday, 9 May: Final Exam (email submission window: 3-10 May)

![]()

Course

Premises, Objectives, & Terms

(continued from above)

Literary Objective 1:

Elements of Tragedy as greatest genre

1a. Tragedy is the greatest

narrative genre of western civilization or

world literature. (Narrative genre

= “contract with the audience” for how a story begins, proceeds, and ends. Other

main narrative genres: romance, comedy)

How do we define greatness?

1b. Special interests:

Narrative as ritual

Greek Tragedy and African culture as unifying artistic

experience (poetry, dance, song, community, world)

Ritual as dance, procession; sacrifice; cf. liturgy,

cult, costumes, masks / masques; cf. communion, baptism, wedding; funeral)

Ritual as reconciliation between humans and gods or

divine.

1c. Formal genre: drama and novel

dramatic art as "imitation," mimesis, or dialogue

fictional art as narrative + dialogue

Essential literary terms:

genre, narrative (story), tragedy, comedy, romance, satire, character, irony,

spectacle, “blood” as family and violence, masks / masques; tragic flaw (hubris,

hamartia), figure of speech; riddle; family romance; personal is political.

Historical Objective 2:

Western Civilization & Postcolonial Africa

2a.

If classical

2b.

If Western Civilization is

modern and Africa

is

traditional, how do Tragedy and Postcolonial

African literature make a dialogue between tradition and modernity?

Other non-western cultures [e.g., Asia] may also be more

traditional than modern

All cultures make some balance b/w stability & change,

past and future

2c.

How does African literature make us see Western

culture differently?

2d.

What advantages to learning history through

representational arts like drama and fiction?

2e.

Tragedy rises

not

when a nation or people are depressed but when they are confident and

enterprising. In contrast, when anxiety and uncertainty unsettle a people or

nation, they turn to popular escapist genres like comedy and romance.

Moral Obj. 3: Are Tragedy &

Multicultural Literature Good 4U?

3a. Literature often functions

as a field of “secular religion” in which

ethical questions are demonstrated and discussed; e.g., Why did this character

act as he or she did? Did this character make the right choice? Why or why not?

3b. Faith-based, mystical, or

other-worldly religions may appear in

literature but usually don’t have final authority. Nothing does! We keep talking

a new world into being.

3c. All people hunger for grand

moral narratives in which characters like us

appear naturally virtuous, heroic, and triumphant, while others (i.e., “them,”

“the bad guys,” “terrorists”) are willfully malicious, hypocritical, and doomed

to defeat.

Popular literature laughs off good characters’ sins or

mistakes (comedy), or shows good & evil as polar extremes, good guys vs. bad

guys, white hats and black hats (romance)—such simple distinctions have wide

appeal.

Tragedy as mental and emotional exercise “beyond good and

evil” (Nietzsche), or thinking rationally and analytically instead of

passionately, deliberately instead of impulsively about human limits.

3d. Aesthetic &

ethical values and terms for tragedy: (Aesthetics

= study of beauty or pleasure; fulfillment of formal expectations; cf. sublime)

How do audiences enjoy tragedy, and why might tragedy do

us good?

Can taste be educated? People naturally like romance,

adventure, spectacle, and happy or triumphant endings, but can we learn to

appreciate tragedy’s subtler, less natural, tougher pleasures?

Contrast easy, push-button

emotions of sentimentality, escapism, triumph.

If

literature’s

purpose is entertainment plus education, do we

learn more from Tragedy?

To assert the purpose of tragic art for a “feel-good”

society.

Is it possible to defend a genre for being less popular?

Can being less popular be a positive quality? On what grounds can such an

anti-democratic or elitist value be defended?

Tragedy as family

values: From the

start Aristotle associates Tragedy with stories of families.

“Happy families are all alike;

each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” (Tolstoy,

Anna Karenina)

Contrast morality &

moralism

morality = honest struggle

to resolve right and right (e.g., abortion, capital punishment; just wars)

moralism = absolute right

and wrong; whoever’s moralizing is right, and whoever disagrees is automatically

wrong.

(Some instructional links for inclusion)

More Africans Enter U.S.

Than in Days of Slavery

![]()

Caryatids, Erechtheion

theater at Epidaurus, 4c BCE