|

Craig White's Literature Courses Critical Sources

Notes to |

|

These links below take you to instructor's notes for each chapter, in case that helps you isolate what's meaningful from Nietzsche's text.

Students should also use the Glossary to Birth of Tragedy to help identify references or obscure vocabulary.

Introduction to Nietzsche and Birth of Tragedy

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is perhaps the most popular, widely read, and consistently influential philosopher in recent Western history, and his Birth of Tragedy (1872, 1886) is the most respected and influential study of tragedy besides Aristotle's Poetics (4th century BCE).

Nietzsche is the philosopher one is most likely to see being read in airports, coffee shops, etc.

He may be the most dashing, daring, disturbing, and readable of serious philosophers.

His philosophy of the "Overman" and the "Superman" who is not bound by traditional rules and laws is attractive to anti-government conservatives who exalt wealthy capitalists as superhuman figures who should not be regulated and taxed. (Compare Ayn Rand.)

Nietzche's popular reputation is far from universally positive. Theists often cite his declaration "God is dead" (while ignoring the quotation's next part: "and humanity has killed Him"). (Compare Karl Marx's description of religion as "the opiate of the people," which is followed by "and the heart of a heartless world.")

Another feature of Nietzsche's life-legend that many educated people know: In the last ten years of his life the great philosopher went insane and, after a series of strokes, became physically and mentally disabled, dying in 1900. For generations Nietzsche's madness was attributed to syphilis, but other historians and analysts now diagnose him as suffering from manic depression or other physiological disorders. (Psychological connections between mental disorders and genius are tantalizingly possible but not definitively proven.)

Nietzsche's legacy to both intellectual and popular culture is enormous. Even if you don't care to read and know his works, the attention he continues to attract testifies to his undeniable stature as one of history's most influential thinkers.

Nietzsche's death in 1900 is often seen as symbolic or prophetic of the twentieth century's descent into World War, totalitarianism, environmental destruction, and other chaotic trends.

Theists, on the other hand, sometimes fairly celebrate Nietzsche's death.

In the twentieth century, a popular graffiti in university restrooms read:

"God is dead."óNietzsche

"Nietzsche is dead."óGod

Unfortunately, Nietzsche's theories of the "ubermensch" (translated as "overman," "superman," or "superhuman") and the "will to power" are sometimes associated with Nazism, Hitler, and the Jewish Holocaust.

Nietzsche himself was not anti-semitic (anti-Jewish) and in fact despised anti-semitism, but after his death, one of his sisters published works associating his ideas with antisemitic thought.

People can still be seen reading Nietzsche in coffee-shops, airports, and on military bases. Appeal:

![]() Nietzsche is always radical. Just being seen reading him says you're brainy but

not soft.

Nietzsche is always radical. Just being seen reading him says you're brainy but

not soft.

![]() Nietzsche is often associated with the radical libertarian philosopher Ayn Rand

(1905-82), who is popular among ideologues of freemarket capitalism and

uninhibited individualism.

Nietzsche is often associated with the radical libertarian philosopher Ayn Rand

(1905-82), who is popular among ideologues of freemarket capitalism and

uninhibited individualism.

![]() Ayn Rand denied Nietzsche's influence on her

writings.

Ayn Rand denied Nietzsche's influence on her

writings.

![]() Nietzsche is

far more highly respected than Rand among professional philosophers.

Nietzsche is

far more highly respected than Rand among professional philosophers.

Next installment: overview of Nietzsche's contributions and where Birth of Tragedy fits in.

Overview: Nietzsche's later works, while still popular for philosophy, are increasingly rigorous, polemical, and of interest to philosophers or to Randian egoists and atheists.

Birth of Tragedy is more interesting and accessible to a Literature course because . . .

1. The subject of Birth of Tragedy is literary, cultural, and historical, written when Nietzsche was a professor of classical literature (esp. Greek and Roman literature). The text discusses Tragedy in grand conceptual terms (e.g. Apolline / Dionysiac), but he refers to characters and works of literature, and his style is literary, full of figures of speech (e.g., metaphors, allusions, symbols).

2. Nietzsche wrote Birth of Tragedy in his twenties, when his style is gentler and more playfully imaginative than in the more darkly confrontational writings of his maturity.

Reading tragedy and philosophy:

No one claims reading philosophy is easy, and only a small proportion of the population ever does.

Most people prefer to have their ideas and identifies reinforced. Most popular literature and culture says that you and people like you are just great or ready to be great. When we come out of a movie where the characters get revenge or achieve true love, we feel similarly rewarded and empowered.

But no real growth or extension of our abilities--no learning.

In contrast, more rigorous forms of literature like tragedy and philosophy challenge, test, and extend us.

Most people back off, and even the people who are willing to take the chance often need to read and re-read, experience and re-experience what works of genius are offering.

Point: if we don't immediately get it and feel rewarded and reinforced, usually we simply say "I don't like it" and return to the world with which we're comfortable.

But if you stay with it on good faith that people of genius aren't just weird monsters but may have something to tell us that we have trouble hearing, then every time you read or experience their work, you get a little closer to what they learned and you may too.

In other words, try to get beyond . . .

"I like it" and "I get it"

to

"I don't know what I'm seeing but it may be worth finding out."

Compare shift from literature "I can identify with" (youth) to literature of strangeness or defamiliarization (maturity).

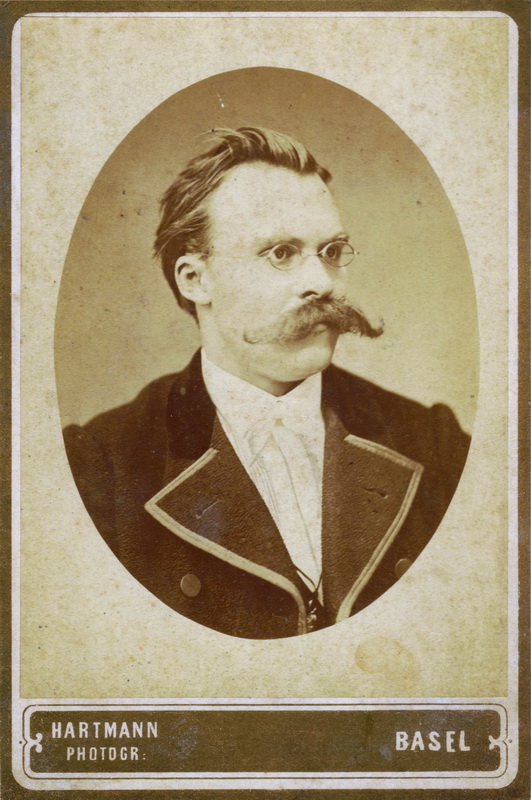

Friedrich Nietzsche ca. 1872

when he was professor of Classical Philology

at University of Basel, Switzerland

and wrote Birth of Tragedy

Takeaways from Birth of Tragedy

1. Apolline / Dionysiac (Apollonian / Dionysian)

|

Apolline |

Dionysiac |

|

order, stability |

disorder, chaos, change |

|

individuation (characters, actors), divisions or borders |

unity, group (chorus), dissolution of borders, inhibitions |

| reason, enlightenment, science | instinct, passion, belief |

2. Chorus as "Birth of Tragedy"

(resolves problem or question of chorus in Greek tragedy: how to teach, rationalize, redeem, or explain the chorus?)

historical: Tragedy began with dithyrambs sung in honor of Dionysus > one person stood as representative of suffering god > Aeschylus added second actor

[Greek tragic hero originally Dionysus, but two are more actors are Apolline b/c individuated]

audience identifies with chorus observing suffering of gods / mythic heroes

mythic: Nietzsche as a late Romantic writer envisions chorus as absorption into or unity with nature > individualized characters as society

cf. myth of Golden Age > contemporary fallen state

cf. Judeo-Christian [Semitic] myth of Eden, union with God > sin & separation from God

cf. Romantic childhood innocence > compromised adulthood

cf. all forms of nostalgia, instinctive human predisposition to glorify past and lament present

audience (with death of tragedy, birth of comedy) identifies not with chorus but with clever, humanistic characters (Euripides)

3. Euripides as death of tragedy

audience pleased, not challenged (see #2 above)

Aeschylus and Sophocles crafted narratives from myth; Euripides bases narratives on myths but brings tragic narratives into realistic, rational world of everyday society.

4. Sin, impiety, transgression against nature or gods > suffering, wisdom

Birth of Tragedy ch. 9, 46-7

Faron & others on tragedy not just being characters dying at end

Also appearance of tragedy with cultural confidence, not despair

Tragedy breaks old system, enables new? > progress?

Oresteia supports: Suffering > wisdom; Eumenides ends personal-vengeance cycle, establishes reconciliation through institutions

Sophocles's final play, Oedipus at Colonus, portrays tragic suffering as blessing, wisdom, transcendence

5. Tragedy originates and reappears as music > heroic opera of Wagner

Nietzsche wrote The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music in two stages:

1772: original chapters of The Birth of Tragedy that our class is reading, concerning origins of Greek tragedy in Chorus of Dionysiac worshippers

1886: additional chapters promoting the revival of the original tragic-mythic power in the Romantic operas of Richard Wagner.

Wagner based most of his operas on Germanic folk tales and Norse legends

Nietzsche and Wagner became friends in the 1880s but later fell out.

The narrative genres and characters are often (though not exclusively) either tragedies or tragic romances.

re-staged as opera (or ballet), but problem of tragedies as elite and educated, comedy and romance as vulgar or popular.)

Liebestod from Wagner's Tristan & Isolde (liebestod = "love-death")

potential significance:

love-death as sublime--both beautiful and threatening