|

Craig White's authors |

|

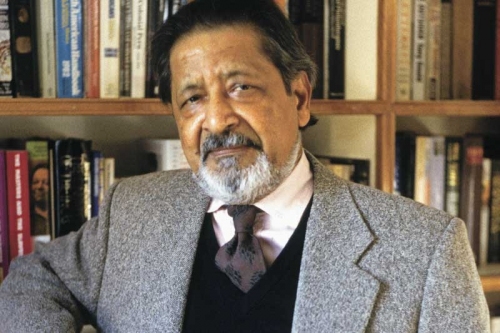

V.S. Naipaul (b. 1932, Trinidad) A Bend in the River (1979) |

|

Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2001, V. S. Naipaul's cosmopolitan lifestyle, prolific publishing, and distinguished style made him an important figure in the literary and critical movements of Postcolonialism in the second half of the twentieth century.

Naipaul was born in Trinidad to parents whose own parents had immigrated there from India in the later 1800s to escape famine and provide labor as indentured servants for sugar plantations in the Caribbean following the abolition of slavery. (British slave trade abolished in 1807; Indian workers also immigrated to British Guiana in northeastern South America.)

|

|

Naipaul's father received enough education to become a journalist with some literary ambitions, a life-story his son re-created in one of his most admired novels, A House for Mr. Biswas (1961). In 1939 Naipaul's family moved to Port of Spain, the Trinidadian capital, where Vidiadhar Sujarprasad (nicknamed Vidia) became an outstanding student. In 1950 he won a Trinidad Government scholarship to study English at Oxford University in England, where he also began to write. At Oxford he met Patricia Ann Hale. Their families opposed their relationship, but they secretly married in 1955. During this time Naipaul produced a regular BBC radio program on Caribbean writers and drafted a novel, Miguel Street, published in 1959.

Across the next half-century, Naipaul published 15 novels and 13 books of nonfiction, many of the latter collecting his extensive travel writing and cultural-historical analysis concerning the colonized and postcolonial world. He won the Booker Prize in 1971, was knighted in 1990, and in 2001 was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for having united perceptive narrative and incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories."

|

|

A Bend in the River (1979) may be Naipaul's most distinguished work of fiction, ranking #83 on the Modern Library's list of the 20th century's greatest novels.

Appearing in 1979, only a year after Orientalism, Edward Said's foundational work in Postcolonial Studies, A Bend in the River became an instant classic of postcolonial fiction.

Though set far from India, Trinidad, or England, the novel's characters and subjects reflect Naipaul's family history in various places and phases of various empires. Instead of presenting the postcolonial voice as one that is either authentic (the colonized) or corrupt (the colonizer), he describes a variety of characters who represent different or overlapping phases of disparate empires, including the postcolonial "Big Man" state in Africa and the Neocolonial empire emerging in the wake of anti-colonialism.

Having previously read one novel and two nonfiction books by Naipaul, I found A Bend in the River surprisingly beautiful and rewarding. If a dependable pleasure in aesthetics is to be surprised by pleasure, or a dependable aesthetic for humanity is finding oneself always able to like or admire a person more, the text and characters of this novel are easy to meet and get to know, but they also keep revealing their intelligence and character in unexpected but impressive ways.

The novel is set in the 1960s in a former British colony in East Africa that resembles Kenya in the years following its independence in 1963. The protagonist-narrator Salim is a member of a Moslem family on the African coast of the Indian Ocean—and implicitly a product or heritage of earlier Moslem or Indian empires (or at least traders). (See Arab, Kenyan)

|

|

|

The novel opens with Salim (b. 1940), the novel's protagonist and narrator, driving from his home in Kenya's Coast Province facing the Indian Ocean, to a trading town in the country's interior. Of his birth community, Salim reports:

![]() The coast was

not truly African. It was an Arab-Indian-Persian-Portuguese place, and we who

lived there were really people of the Indian Ocean. True Africa was at our back.

. . . [W]e looked east to the lands with which we traded--Arabia, India, Persia.

These were also the lands of our ancestors. But we could no longer say that we

were Arabians or Indians or Persians; when we compared ourselves with these

people, we felt like people of Africa.

The coast was

not truly African. It was an Arab-Indian-Persian-Portuguese place, and we who

lived there were really people of the Indian Ocean. True Africa was at our back.

. . . [W]e looked east to the lands with which we traded--Arabia, India, Persia.

These were also the lands of our ancestors. But we could no longer say that we

were Arabians or Indians or Persians; when we compared ourselves with these

people, we felt like people of Africa.

![]() My family was

Muslim. But we were a special group. We were distinct from the Arabs and other

Muslims of the coast; in our customs and attitudes we were closer to the Hindus

of northwestern India, from which we had originally come. When we had come no

one could tell me. We were not that kind of people. We simply lived; we did what

was expected of us, what we had seen the previous generation do. (10-11)

My family was

Muslim. But we were a special group. We were distinct from the Arabs and other

Muslims of the coast; in our customs and attitudes we were closer to the Hindus

of northwestern India, from which we had originally come. When we had come no

one could tell me. We were not that kind of people. We simply lived; we did what

was expected of us, what we had seen the previous generation do. (10-11)![]()

With Kenya's independence, this small coastal Muslim community is broken up. Indigenous Africans confiscate their properties, leading Salim to purchase a shop in the interior trading town from Nazruddin, his mentor and a businessman who is relocating his operations to Uganda (in central Africa). Salim is more or less betrothed to Nazruddin's daughter Kareisha (who is regularly referred to but never directly appears). Accompanying Salim from his home is a family slave, Metty, who is half-African and whose name derives from a French word (metis) for mixed blood.

Salim sells simple goods like toothbrushes, razors, and aluminum pans. One of his best customers is Zabeth, an African market woman who trades with villages deep in the forest. Zabeth is herself an outsider who reputedly protects herself with magic. At length she leaves her son Ferdinand (sired by a father from yet another African region) under Salim's guidance when he enrolls in a military school near the town.

The unnamed town, when Salim arrives there, is half-destroyed by the war for Independence, and the town's cathedral and the European suburb—known as the Domain—are in ruins. "The Big Man," who led the nation to independence and now serves as president, builds a half-finished industrial park in the Domain and adds new housing as outside experts arrive to help with the land's renewal. Indar, a childhood friend of Salim's in his birth community, arrives after studying in London and introduces Salim to Raymond, a British historian who plans a study of the new nation but mostly publishes prestigious propaganda for the Big Man. Yvette, Raymond's younger Belgian wife, begins an extended affair with Salim.

The Big Man, who may be partly modeled after Kenya's Independence leader and founding President Jomo Kenyatta, appears directly only briefly in the novel, but his presence and his plans for the country both encourage the town's development and, increasingly, threaten it. The novel repeatedly notes the Big Man's appearance in oversized photos and paintings in public places, a familar technique of authoritarian governments dedicated to a Cult of Personality (e.g., Hitler, Stalin, Mao).

Amid this rising dread and uncertainty, the theme or lesson of the novel recurs to a realization by Indar who studied in London and attempted to join the diplomatic corps of his home country through its offices there but was rejected because his Indian-African descent bespoke "divided loyalties" (149). Perceiving that the postcolonial state is as racist and corrupt as the colonial empire, Indar refects:

![]() We have to

learn to trample on the past, Salim. . . . It isn't easy

to turn your back on the

past. It isn't something you can decide to do just like that. It is somethign

you have to arm yourself for, or grief will ambush and destroy you. . . . (141)

We have to

learn to trample on the past, Salim. . . . It isn't easy

to turn your back on the

past. It isn't something you can decide to do just like that. It is somethign

you have to arm yourself for, or grief will ambush and destroy you. . . . (141)

![]() I had begun to

understand . . . that my anguish about being a man adrift was false, that for me

that dream of home and security was nothing more than a dream of isolation,

anachronistic and stupid and very feeble. I belonged to myself alone. . . .

(151)

I had begun to

understand . . . that my anguish about being a man adrift was false, that for me

that dream of home and security was nothing more than a dream of isolation,

anachronistic and stupid and very feeble. I belonged to myself alone. . . .

(151)

At length the Big Man's programs rely for support on appeals to indigenous Africans, making the town's conditions for non-natives unstable. Eventually Salim can flee only by the aid of Ferdinand, who has re-appeared as the town's military boss. The river on which Salim escapes by steamboat has been a recurrent feature and symbol of the landscape's perilous history. The steamboat tows a passenger barge. At sunset dozens of dugouts rush out to the larger boats but are ambushed by soldiers.

![]() It was in this

darkness that abruptly, with many loud noises, we stopped. There were shouts

from the barge, the dugouts with us, and from many parts of the steamer. Young

men with guns had boarded the steamer and tried to take her over. But they had

failed; one young man was bleeding on the bridge above us. The fat man, the

captain, remained in charge of his vessel. We learned that later.

It was in this

darkness that abruptly, with many loud noises, we stopped. There were shouts

from the barge, the dugouts with us, and from many parts of the steamer. Young

men with guns had boarded the steamer and tried to take her over. But they had

failed; one young man was bleeding on the bridge above us. The fat man, the

captain, remained in charge of his vessel. We learned that later.

![]() At the same

time what we saw was the steamer searchlight, playing on the riverbank, playing

on the passenger barge, which had snapped loose and was drifting at an angle

through the water hyacinths at the edge of the river. The searchlight lit up the

barge passengers, who, behind bars and wire guards, as yet scarecely seemed to

understand that they were adrift. Then there were gunshots. The searchlight was

turned off; the barge was no longer to be seen. The steamer started up again and

moved without lights down the river, away from the area of battle. The air would

have been full of moths and flying insects. The searchlight, while it was on,

had shown thousands, white in the white light.

At the same

time what we saw was the steamer searchlight, playing on the riverbank, playing

on the passenger barge, which had snapped loose and was drifting at an angle

through the water hyacinths at the edge of the river. The searchlight lit up the

barge passengers, who, behind bars and wire guards, as yet scarecely seemed to

understand that they were adrift. Then there were gunshots. The searchlight was

turned off; the barge was no longer to be seen. The steamer started up again and

moved without lights down the river, away from the area of battle. The air would

have been full of moths and flying insects. The searchlight, while it was on,

had shown thousands, white in the white light.

END