|

Craig White's Literature Courses Critical Sources

Notes to Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

Chapter 12 |

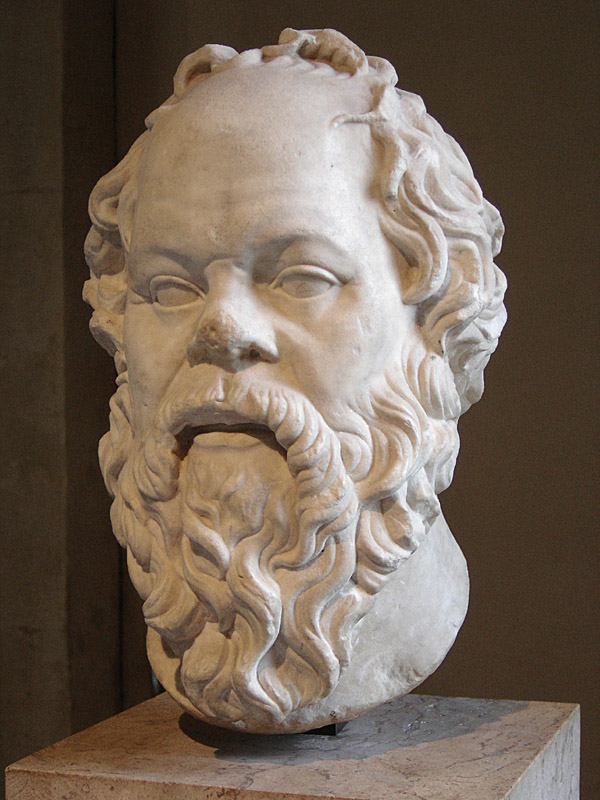

Socrates (bust), the Louvre |

[Instructor's notes: start with Dionysiac / Apolline (exemplified by tragedies of Aeschylus & Sophocles)

> with Euripides, dialectic becomes Dionysian / Socratic (Classical Greek Poets & Philosophers)

Dionysian chorus as primitive myth; abandonment to conditions, instinct

Review chapter 11:

55 Euripides brought

the spectator on stage

58

two

spectators as sole judges and masters competent to judge

One = Euripides himself as thinker: richness of critical talent

59 > 2nd spectator who did not understand tragedy and therefore chose to ignore it

Chapter 12

59 name for 2nd

spectator? >

Contradictory and

incommensurable elements of Aeschylean tragedy

Duality of chorus

and tragic hero = Apolline & Dionysiac

intention

of Euripides:

excision of primitive and powerful Dionysiac, rebuilding of tragedy on non-Dionysian

60

Dionysus bewitches intelligent adversary: e.g., Pentheus in

Bacchae

Cadmus and

Tiresias (and Euripides): the reasoning of the cleverest individual cannot overthrow ancient

popular traditions

[Euripides’s]

tragedy is a protest against the fulfillment of his intentions

Dionysus hounded

from stage by a daemonic power that spoke through Euripides

Euripides merely a mask: deity that

spoke was a new-born daemon named

Socrates

New opposition:

Dionysiac and Socratic

Conflict >

downfall of Greek tragedy

Socratic intention

vanquished Aeschylean tragedy

[from glossary: 60 the Socratic intention: Nietzsche argues that Socrates, founder of Western philosophy, believes that intellectual analysis generates and disseminates goodness in the leadership and citizenry, and that . . .

Euripides’s tragedies imitate this process when their protagonists explicate and defend their motivations in a context of rational humanistic comprehension and an everyday world they share with the average citizen.

In contrast, according to Nietzsche, the earlier Greek tragedians

(Aeschylus and Sophocles) did not rely on a rationally enlightened world but

brought spectators into contact with a deeper, irrational, ecstatic existence

embodied in myth and mystery (or, following Dionysus, intoxication or altered

mental states).

61 > a

dramatized epic:

an Apolline sphere of art in which

tragic

effects were impossible.

Power of Apolline

epic: entirely illusion and delight and redemption in illusion

Internal dreaming;

therefore never entirely an actor

Euripides draws up

the plan as a Socratic thinker, puts it into effect as a passionate actor

Euripidean tragedy . . . has made the greatest possible break with the Dionysiac elements

needs new stimuli, neither Apolline

or Dionysiac: cool, paradoxical

thoughts

62 Euripides achieves fiery emotions rather than Dionysiac ecstasies

Highly realistic counterfeits, inartistic naturalism

Phenomenon of

aesthetic

Socratism: “to be beautiful everything must

first be intelligible.”

Insistent critical process

Euripidean

prologue: what will happen; therefore no suspense, tension

Pathos rather than plot

A missing link for listener, gap in mesh of preceding story

63 In these

opening scenes Aeschylus and Sophocles employed the subtlest devices to give the

spectator, as if by chance, all the threads that he would need for a complete

understanding; a feature which preserves the noble artistry that masks the

necessary

formal element, making it look accidental.

Euripides’s prologue before exposition via deity: cf. notorious deus ex machina

Anaxagoras / Euripides first sober philosopher / poet in a

company of drunkards

Sophocles on Aeschylus: did right thing but unconsciously

64 Plato: poets cf. soothsayers & oneiromancers

‘everything must be conscious before it can be beautiful”

Socrates = 2nd

spectator who didn’t understand the older tragedy

Socrates = new Orpheus against Dionysus

Euripides