|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

Walt Whitman

Whitman's Status, Style,

|

Whitman (1819-92) |

Whitman is widely celebrated as "America's greatest poet." Such "greatness" is neither exclusive nor comprehensive, as the work of other American poets—Dickinson, Stevens, Eliot, Frost, Plath, Lowell—may be finer, subtler, or more learned.

Whitman's greatness stands on some important facts of literary history:

![]() Whitman enjoyed

a long and highly productive career,

compared to many poets. He wrote (and continually revised) a vast number of poems of varying

quality.

Whitman enjoyed

a long and highly productive career,

compared to many poets. He wrote (and continually revised) a vast number of poems of varying

quality.

![]() Whitman is the

first great poet to write extensively in

"free verse."

His development of this style advanced its development among most major poets

since.

Whitman is the

first great poet to write extensively in

"free verse."

His development of this style advanced its development among most major poets

since.

![]() Corresponding to changes in poetic

style, Whitman changed the subject matter of poetry.

Corresponding to changes in poetic

style, Whitman changed the subject matter of poetry.

![]() These changes in style and subject relate poetry to common

life

These changes in style and subject relate poetry to common

life

![]() Free verse

tries to imitate normal speech and everyday language (though still elevated

in some ways)

Free verse

tries to imitate normal speech and everyday language (though still elevated

in some ways)

![]() Whitman's

poetry attempts to make poetic the everyday events of common life. Instead

of Romantic scenes featuring noble knights and fair ladies, his poetry

describes common American men and women in the city and on the frontier.

Whitman's

poetry attempts to make poetic the everyday events of common life. Instead

of Romantic scenes featuring noble knights and fair ladies, his poetry

describes common American men and women in the city and on the frontier.

![]() Ironically,

unschooled people rarely admire Whitman as much as educated elites.

(Common people prefer sing-song rhymes and escapist sentiments)

Ironically,

unschooled people rarely admire Whitman as much as educated elites.

(Common people prefer sing-song rhymes and escapist sentiments)

![]() Whitman is

the most influential American poet,

nationally

and internationally:

Writers influenced by Whitman.

Whitman is

the most influential American poet,

nationally

and internationally:

Writers influenced by Whitman.

![]() Whitman's poetry sometimes has a

wince-factor that puts off

readers, but like other other great authors, the longer you know him, the more

you admire.

Whitman's poetry sometimes has a

wince-factor that puts off

readers, but like other other great authors, the longer you know him, the more

you admire.

Great poetry merges style and subject. Whitman's experiments in free verse complement his experiments in subject matter. Free verse frees subject matter.

![]()

Whitman as "revolutionary" poet.

![]() Readers today find his style of poetry familiar—wide-open

in term of style and subject matter

Readers today find his style of poetry familiar—wide-open

in term of style and subject matter

![]() But in the mid-1800s Whitman was a revolutionary—no one

had written poetry like his before. (A few had experimented, but Whitman stayed

with it.)

But in the mid-1800s Whitman was a revolutionary—no one

had written poetry like his before. (A few had experimented, but Whitman stayed

with it.)

![]() "free verse" instead of structured, rhymed,

metrical lines of

formal verse

"free verse" instead of structured, rhymed,

metrical lines of

formal verse

![]() poetry not just about pretty, heroic, or uplifting

subjects, but poetry engages intimacies and complexities of modern

life.

poetry not just about pretty, heroic, or uplifting

subjects, but poetry engages intimacies and complexities of modern

life.

![]()

|

Whitman's stylistic techniques Free verse poetry dispenses with regular rhyme and meter but is never completely free of poetic conventions: figures of speech (esp. metaphor), alliteration and assonance, occasional or interior rhymes, and rhetorical enhancements of everyday speech. Formal qualities of Whitman's free verse:

Stylistic eccentricities:

|

from "There Was a Child Went Forth"

The early lilacs became part of this child,

And grass and white and red morning-glories, and white and red clover, and the song of the phoebe-bird,

And the Third-month lambs and the sow's pink-faint litter, and the mare's foal and the cow's calf,

And the noisy brood of the barnyard or by the mire of the pond-side,

And the fish suspending themselves so curiously below there, and the beautiful curious liquid,

And the water-plants with their graceful flat heads, all became part of him.

The field-sprouts of Fourth-month and Fifth-month became part of him, |

![]()

Whitman's subject matter & themes

Whitman's subject matter diverged sharply from most popular and classic poetry up to his time.

-

Much classic poetry of the Romantic era developed subjects far from everyday life, deep in an idealized past, far from the city life that more and more readers experienced, or high in the realm of intellect or fantasy.

-

Much popular poetry of the American Renaissance was sentimental, glorifying domestic life or describing daring adventures.

Comparatively, Whitman's subject matter was intimate, raw, exploratory, unafraid of descending into dirt and potential degradation. Instead of poetry just being about flowers or heroes of the past and their noble sentiments, poetry becomes more about everyday life, including the streets and farms of common American life, its common people, and the problems they face in terms of democracy, sexual identity, race, etc.

Consequently, Whitman incorporates literary Realism even though he wrote mostly during the Romantic era.

Whitman's themes:

-

Shifting relations between self and other, soul and nature, the individual and the masses—sometimes one is absorbed in the other, sometimes they separate and stand apart before rejoining (correspondence)

-

Identification and inclusiveness (correspondence + catalog)

-

Mystical transcendence and absorption (correspondence)

-

Sexually suggestive imagery

-

Courage and honesty—Whitman faces what needs to be faced. Poetry is not an evasion or escape but a direct, highly-charged encounter.

Whitman's poetry works to resolve a problem in American society that can't be resolved except poetically or mystically.

- All Americans are equal.

- Each American is special, unique, an individual.

Inherent contradiction between equality and individuality?

Some resolutions:

-

"what I assume you shall assume"

-

"opposite equals advance"

-

self-other & union (sexual, mystical, or both)

![]()

What's Romantic about Whitman?

-

heroic individualism (balanced by attempts to connect self w/ other)

-

some poems follow romance narrative of quest or journey

-

evocations of nature as sublime, spiritualized, sometimes seen through child-like eyes

-

tender depictions of human relations and sentiments

-

bold new ideas and depictions such as human equality including race, women, alternative sexualities

![]()

What's Realistic about Whitman?

-

attention to detail may evoke particular time and place

-

Whitman is an urban poet who often depicts the emerging American reality of city life instead of the nostalgia of country life

-

Whitman mixes good and bad instead of setting them in stark Romantic opposition.

![]()

Teaching Whitman

Like Emerson, Whitman so exceeds every category and offers

so many radiating lines of thought, that controlling or guiding a discussion may

be futile.

As with Emerson, some students will be inspired—"I never liked poetry, but I like this."

On the other hand, some students who already like poetry will find Whitman crude and offensive, or they'll miss the more musical qualities that free verse gives up.

Overall, Whitman's not especially complicated, but there's also no end to him, either in the number of poems he wrote or the number of different angles from which they may be read.

![]()

Whitman as "America's Greatest Poet?"

Whitman is generally regarded as "the greatest American poet." Such a description is not necessarily the same as "the best," "the finest," "the most accomplished," "the most brilliant" poet, etc.

What makes a great writer or artist?

Quality of work: attracts, intrigues, challenges, motivates audience

*Whitman's poetry continually attracts and rewards new readers.

Significance of work: A great artist's work does not escape from the problems of the world but engages and, as far as possible, resolves them.

*Whitman is the "greatest American poet because more than any other he gives voice to some of the great themes or issues that animate the nation or people. Whitman’s most persistent American theme is (from objective 3) “the individual and the community,” which might be rephrased thus: How can you have a community of individuals? How can everyone be special and equal? ("Song of Myself" introduces him as "Walt Whitman, an American.")

Quantity of work: most great artists are highly productive, not just creating one masterpiece but a number of important pieces

*Nearly all of Whitman's best work appeared in the first 10 years of his career (1855-1865), but he always continued writing new poems, refining old poems, promoting his career.

Maturation, development, variation across career: great artists try different ideas, media, techniques—not just "one-trick ponies"

*Our first 3 poems appear in 1855-56 and demonstrate the breakthrough of the Whitman style, but "Lilacs" in 1865 shows some maturation of the style.

Great artists inherit and extend other artists' work: they know what's happened before, honoring, challenging, extending it.

*Though not classically educated, Whitman read widely in popular and classical literature, honored Emerson and other predecessors and saw himself as fulfilling their mission.

Great artists reshape or reform or revolutionize media and genres.

*Perhaps Whitman's greatest contribution. In poetry, Whitman both "freed verse" and opened poetry to new subjects, themes, contents (no longer was poetry "just pretty flowers," etc.)

Just as great artists are influenced by previous ones, so they influence other artists.

*It's commonly acknowledged that all American poets must come to terms with Whitman, either following in his style (Stevens, Ginsberg) or reacting against it (T. S. Eliot).

pro: (wild people, experimental forms,

raw emotions): Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Elizabeth Bishop, Diane

Wakowski, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Thomas Wolfe, + many others

con: (refined people, style, and subjects): T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Dickinson, Marianne Moore

*Whitman also has considerable international influence. He was admired by contemporary British poets such as Tennyson and Swinburne, whom he influenced. His free-verse style also influenced continental European poets in France and Italy, etc.

*Compared to tightly focused and quirkily lyrical poets like Dickinson, Whitman translates well.

*Whitman's style and subject matter also

influential on South and Central American poets: Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, J. L. Borges

If interested in Neruda, see Il Postino (The Postman)

*Whitman widely seen as the first great modern poet, in terms of poetic style and lifestyle.

Lifestyle: artist as bohemian, non-conformist, “other,” outsider trying to connect.

+ freeing of verse & expansion of

poetic subject matter shook up poetic world, now standard

Whitman's life and image.

|

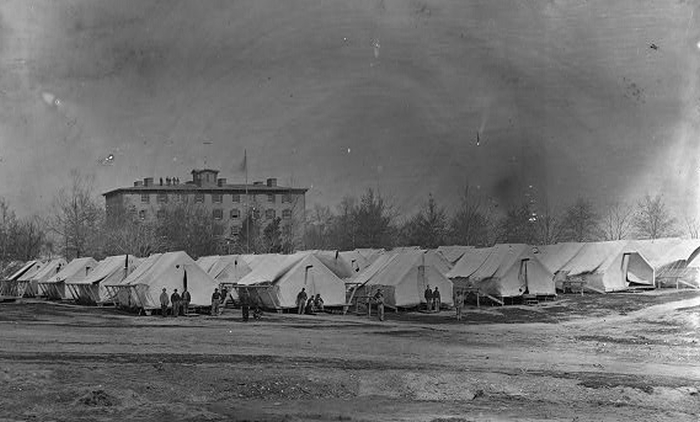

Whitman was born in 1819 on Long Island in a rural area near New York City and grew up there and in Brooklyn as part of a large working-class family whose mother was of Quaker descent and whose father knew Thomas Paine, the most radical of the USA's founders. Whitman's formal schooling ended at age 11, after which he worked in print shops and taught school on Long Island, then moved to New York City to write for and edit several newspapers (then a booming industry). In the city Whitman frequented public libraries, attended operas, plays, and lectures, and joined a debating society. Around 1850 Whitman began composing the poems that in 1855 formed his first (and continuing) book of poety, Leaves of Grass, which he self-printed and published. Like most books of poetry, Leaves of Grass drew little general attention, but the reaction it received was sharply divided between those who regarded his work as crude and reckless, and a few who saw its revolutionary potential. For the rest of his life, in the face of critical indifference, disgust, and occasional validation, Whitman continued to write and publish poems that were added to Leaves of Grass. In 1862 during the Civil War, one of Whitman's brothers was wounded, leading the poet, then in his early 40s, to travel to Washington DC, where he found his brother in good condition, but Whitman stayed to help with the many wounded soldiers at makeshift hospitals there. For three years Whitman worked in the day as a clerk in government offices, then spent afternoons raising money and other contributions to aid the wounded, whom he visited most nights, working as a nurse's aide, writing letters for, and otherwise helping the wounded and their attendants. > |

Whitman's wartime labors prematurely aged him, and in the 1870s he suffered a series of disabling strokes. Aided by a small but growing number of admirers, Whitman continued to write and support himself not only through poetry but occasional journalism and lectures until his death in 1892. Whitman's sexuality has always been an important or controversial dimension to his image as a great American poet. Despite his occasional protests and cover-ups, he maintained a series of same-sex relations, typically with younger working men. His hospital work during the Civil War is often interpreted as providing a socially-permitted expression of his instinctive affection for young men. Whitman as prototypical modern gay poet:

|

|

|

|