|

Craig White's Literature Courses Formal or Fixed Verse (compare free verse) |

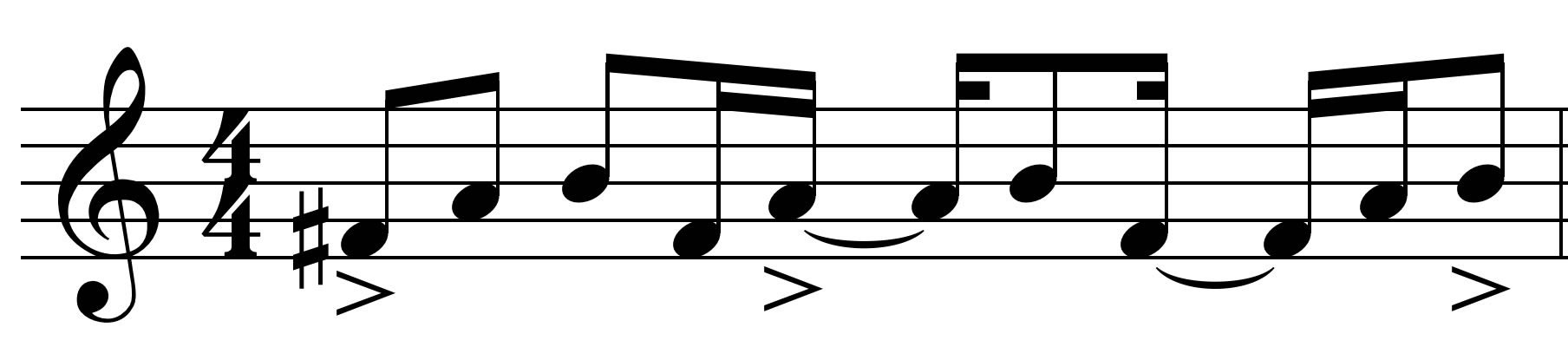

Rhyme & rhythm (meter) helped singers memorize epic poems like The Iliad or Beowulf, which were sung & heard, not read |

Formal or fixed verse takes many different forms, but since

the advent of free verse it refers especially to

poetry with intentional, regular rhymes and rhythm or meter that

enhance the sonic or musical effects of language.

Meter is "the beat" or rhythmic structure of lines in a poem. The most familiar metric line for English speakers is iambic pentameter, found in Shakespeare's plays and the blank or heroic verse of John Milton’s epic Paradise Lost, and other formal poems and classical English drama. (Examples below.)

Rhyme is repetition (in English) of vowel and consonant sounds, usually at the end of a line, as in the rhyming couplet (2-line unit) that concludes Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29:

For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

Besides end-rhyme, these lines'

meter is

iambic pentameter—each line has five 2-stroke “feet”

with an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (think of "feet" as

"steps," like in a dance):

for THY sweet LOVE reMEMbered SUCH wealth BRINGS

that THEN i SCORN to CHANGE my STATE with KINGS.

(No one really speaks the poem in a perfectly sing-song way, but the lines' formal regularity aids memorization and adds order and beauty.)

Other essential terms for formal verse:

Stanzas (Oxford English Dictionary): A group of lines of verse . . . arranged according to a definite scheme which regulates the number of lines, the metre, and (in rhymed poetry) the sequence of rhymes; normally forming a division of a song or poem consisting of a series of such groups constructed according to the same scheme.

Common types of stanzas: quatrain (4 lines), couplet (2 lines), triplet (3 lines).

Prosody or the study of verse meters considers many varieties of metric feet (e.g., iamb, trochee, spondee) and lines (pentameter, tetrameter, trimester), as well as stanza units of lines including couplet, triplet, quatrain, sestet, octet, which may appear in countless poetic genres such as ballad, sonnet, ode, villanelle, rondeau, etc.

Such units may appear more technical and forbidding than they are; many such forms thrive in popular songs, where even if you don’t know the terms you can tell when a line has too many syllables or feet, or when a rhyme sounds forced or wrong.

Rhymes too have variants such as half-rhymes, sight-rhymes, and internal rhymes instead of end-rhymes.

![]()

Historic Background for Formal Verse

(Since most poetry today isn't fixed or formal, why was it in the past?)

Fixed verse's many forms are the work of many days for devoted students, but why did these forms dominate poetry of the past?—especially since free vers is the assumed form of more recent or modern poetry?

The short answer is poetry's association with music and song. Like songs even today, poetry in the past was experienced not so much on the page but more in person, heard aloud, in sung or spoken forms, and the poet or singer was expected to know poetry by memory, just as singers at a concert or actors on a stage are expected to memorize their lines.

In brief, meter and rhyme are MNEMONIC or MEMORY-REINFORCING: regular rhythm and rhyme cue the memory to what comes next.

As easy proof, many students sooner or later have to memorize and recite a poem or a passage from a play. Almost invariably the poem assigned will be rhymed or metrical or both.

In contrast, the exact form of free verse is comparatively hard to remember and recite. In contrast to the spoken or oral tradition that underlies formal poetry, free verse appeared in the mid-1800s simultaneous with the industrial expansion of printing that made books and magazines available to a growing class of literate people.

Formal verse has revived somewhat in the past generation with the New Formalism movement.

Otherwise formal verse survives in greeting cards and didactic poetry, which may unfortunately associate fixed forms with cliched sentiments or simple morals.

![]()

Blank or Heroic Verse in English

Oxford English Dictionary. blank verse n. verse without rhyme; esp. the iambic pentameter or unrhymed heroic, the regular measure of English dramatic and epic poetry . . .

Examples of Blank or Heroic Verse (i.e. unrhymed iambic pentameter)

John Milton, Paradise Lost (1674)—opening lines:

Of Man's First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that

Forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste

Brought Death into the World, and all

our woe,

With loss of EDEN, till one greater Man

Restore us, and

regain the blissful Seat . . . .

(Milton referred to this form as "English heroic verse without rhyme," but the 17th century also referred to it as "blank verse.")

![]()

Other popular examples of "heroic" or "blank verse" (unrhymed iambic pentameter):

Most parts of Shakespeare's plays are written in blank verse, e.g. . . .

from Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet (ca. 1595), Act 2, Scene 2

Romeo: Lady, by yonder blessed moon I vow

That tips with silver all these fruit-tree tops.

Juliet: O, swear not by the moon, the

inconstant moon,

That monthly changes in her circled orb,

Lest that thy

love prove likewise variable.

![]()

Ulysses (1833, 1842) by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

. . . 'Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

Push

off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose

holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars,

until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down;

It may be we

shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. . . .

(ll. 57–64)

![]()

Harlem Dancer (1922) by Claude McKay

Applauding youths laughed with young

prostitutes

And watched her perfect,

half-clothed body sway;

Her voice was like the sound of

blended flutes

Blown by black players upon a picnic day. . . .

(ll. 1-4)

![]()

Examples of formal or fixed verse:

William Blake, "The Tyger" (1794)

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Sonnets from the Portuguese, #43 ("How do I love thee? . . . )

Robert Burns, "A Red, Red Rose" (1794)

Robert Frost, "The Road Not Taken" (1915)

Thomas Hardy, "The Oxen" (1915)

A. E. Housman, from A Shropshire Lad, #40 ("Into my heart an air that kills")

Claude McKay, "Harlem Shadows" (1922)

Claude McKay, "America" & "The White City" (sonnets)

Edgar Allan Poe, "Annabel Lee" (1849)

William Ernest Henley, "Invictus" (1875)