|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

Selections from James Fenimore Cooper A Narrative of 1757 (1826)

from chapters 16 & 17 |

The Last of the Mohicans (1936), on whose screenplay the 1992 film was based |

![]()

from Chapter 16

[16.1]

Major Heyward found Munro attended only by his daughters.

[16.2]

Not only the dangers through which they had passed, but those which still

impended above them, appeared to be momentarily forgotten, in the soothing

indulgence of such a family meeting. It seemed as if they had profited by the

short truce

[b/w English and French armies],

to devote an instant to

the purest and

best affection; the daughters forgetting their fears, and the veteran his

cares, in the security of the moment. Of this scene, Duncan, who, in his

eagerness to report his arrival, had entered unannounced, stood many moments an

unobserved and a delighted spectator. But the quick and dancing eyes of

[16.3]

"Major Heyward!”

[16.4]

"What of the lad?” demanded her father; "I have sent him to crack

[negotiate]

a little with the Frenchman. Ha, sir, you are young, and you're nimble! Away

with you, ye baggage; as if there were not troubles enough for a soldier,

without having his camp filled with such prattling hussies as yourself!”

[16.5]

Alice laughingly followed her sister, who instantly led the way from an

apartment where she perceived their presence was no longer desirable.

Munro, instead of demanding the result of the young man's mission, paced the

room for a few moments, with his hands behind his back, and his head inclined

toward the floor, like a man lost in thought. At length he raised his eyes,

glistening with a father's fondness, and exclaimed:

[16.6]

"They are a pair of excellent girls, Heyward, and such as any one may boast of.”

[16.7]

"You are not now to learn my opinion of your daughters, Colonel Munro.”

[16.8]

"True, lad, true,” interrupted the impatient old man; "you

were about opening your mind more fully on that matter the day you got in, but I

did not think it becoming in an old soldier to be talking of nuptial blessings

and wedding jokes when the enemies of his king were likely to be unbidden guests

at the feast. But I was wrong,

[16.9]

"Notwithstanding the pleasure your assurance gives me, dear sir, I have just

now, a message from Montcalm—"

[16.10]

"Let the Frenchman and all his host go to the devil, sir!” exclaimed the hasty

veteran. "He is not yet master of William Henry, nor shall he ever be, provided

Webb* proves himself the man he should. No, sir, thank Heaven we are not yet in

such a strait that it can be said Munro is too much pressed to discharge the

little domestic duties of his own family.

[16.11]

“Your mother was the only child of my bosom friend, Duncan;

and I'll just give you a hearing, though all the knights of

[16.12]

Heyward, who perceived that his superior took a malicious pleasure in exhibiting

his contempt for the message of the French general, was fain to humor a spleen

[temper]

that he knew would be short-lived; he therefore, replied with as much

indifference as he could assume on such a subject:

[16.13]

[Heyward:]

"My request, as you know, sir, went so far as to presume to the honor of being

your son.”

[16.14]

[Munro:]

"Ay, boy, you found words to make yourself very plainly comprehended. But, let

me ask ye, sir, have you been as intelligible to the girl?”

[16.15]

"On my honor, no,” exclaimed

[16.16]

[Munro:]

"Your notions are those of a gentleman, Major Heyward, and

well enough in their place.

But Cora Munro is a maiden too discreet, and of a mind too

elevated and improved, to need the guardianship even of a father.”

[16.17]

[

[16.18]

[Munro:]

"Ay—Cora! we are talking of your pretensions to Miss Munro, are we not, sir?”

[16.19]

"I—I—I was not conscious of having mentioned her name,”

said

[16.20]

"And to marry whom, then, did you wish my consent, Major

Heyward?” demanded the old soldier, erecting himself in

the dignity of offended feeling.

[16.21]

"You have another, and not less lovely child.”

[16.22] "

[16.23]

"Such was the direction of my wishes, sir.”

[16.24]

The young man awaited in silence the result of the

extraordinary effect produced by a communication, which, as it now appeared, was

so unexpected. For several minutes

Munro

paced the chamber with long and rapid strides, his rigid features working

convulsively, and every faculty seemingly absorbed in the musings of his own

mind. At length, he paused directly in front of Heyward, and riveting his eyes

upon those of the other, he said, with a lip that quivered violently:

[16.25]

"Duncan Heyward, I have loved you for the sake of

him whose blood* is in your veins

; I have loved you for your own good qualities; and I have loved you, because I

thought you would contribute to the happiness of my child. But all this love

would turn to hatred, were I assured that what I so much apprehend

[fear]

is true.”

[16.26]

"God forbid that any act or thought of mine should lead to such a change!”

exclaimed the young man, whose eye never quailed under the penetrating look it

encountered. Without adverting to the impossibility of the other's comprehending

those feelings which were hid in his own bosom, Munro suffered himself to be

appeased by the unaltered countenance he met, and with a voice sensibly

softened, he continued:

[16.27]

"You would be my son, Duncan, and

you're ignorant of the history of the

man you wish to call your father. Sit ye down, young man, and I will open to

you the wounds of a seared

[scorched]

heart, in as few words as may be suitable.”

[16.28]

By this time, the message of

[French General]

Montcalm was as much forgotten by him who bore it

[

[16.29]

[Munro:]

"You'll know, already, Major Heyward, that

my family was both ancient and honorable,”

commenced the Scotsman; "though it might

not altogether be endowed with that amount of wealth that should correspond

with its degree. I was, maybe, such an one as yourself when I plighted my faith

to Alice Graham, the only child of a neighboring laird

[landowner]

of some estate.

[16.30]

[Munro continues:]

“But the connection was disagreeable to her father, on more accounts than my

poverty. I did, therefore, what an honest man should—restored the maiden her

troth

[freed her from their engagement],

and departed the country in the

[military]

service of my king. I had seen many regions, and had shed

much blood in different lands,

before

duty called me to the islands of the West Indies

[

[16.31]

[Munro continues:]

There it was

my lot

to form a connection with one who in time became my wife, and the mother of

Cora. She was the daughter of a gentleman of those isles, by a lady whose

misfortune it was, if you will,” said the old man, proudly, "to

be descended, remotely, from that unfortunate class who are so basely enslaved

to administer to the wants of a luxurious people.

[Cora is part African]

Ay, sir, that is a curse, entailed on

[16.32]

"'Tis most unfortunately true, sir,” said

[16.33] "And you cast it on my child as a reproach!

You scorn to mingle

the blood of the Heywards with one so degraded—lovely and virtuous though she

be?” fiercely demanded the jealous parent.

[16.34]

"Heaven protect me from a prejudice so unworthy of my reason!” returned Duncan,

at the same time conscious of such a feeling, and that as deeply rooted as if it

had been engrafted in his nature.

"The sweetness, the beauty, the witchery of your younger daughter, Colonel

Munro, might explain my motives without imputing to me this injustice.”

[16.35] "Ye are right, sir,” returned the old man, again changing

his tones to those of gentleness, or rather softness; "the girl is the image of

what her mother was at her years, and before she had become acquainted with

grief. When

death deprived me of my wife I returned to

[16.36]

"And became the mother of

[16.37]

"She did, indeed,” said the old man, "and dearly did she pay for the blessing

she bestowed. But she is a saint in heaven, sir; and it ill becomes one whose

foot rests on the grave to mourn a lot so blessed. I had her but a single year,

though; a short term of happiness for one who had seen her youth fade in

hopeless pining.”

[16.38]

There was something so commanding in the distress of the old man, that Heyward

did not dare to venture a syllable of consolation. Munro sat utterly unconscious

of the other's presence, his features exposed and working with the anguish of

his regrets, while heavy tears fell from his eyes, and rolled unheeded from his

cheeks to the floor. At length he moved, and as if suddenly recovering his

recollection; when he arose, and taking a single turn across the room, he

approached his companion with an air of military grandeur, and demanded:

[16.39]

"Have you not, Major Heyward, some communication that I should hear from the

marquis de Montcalm?”

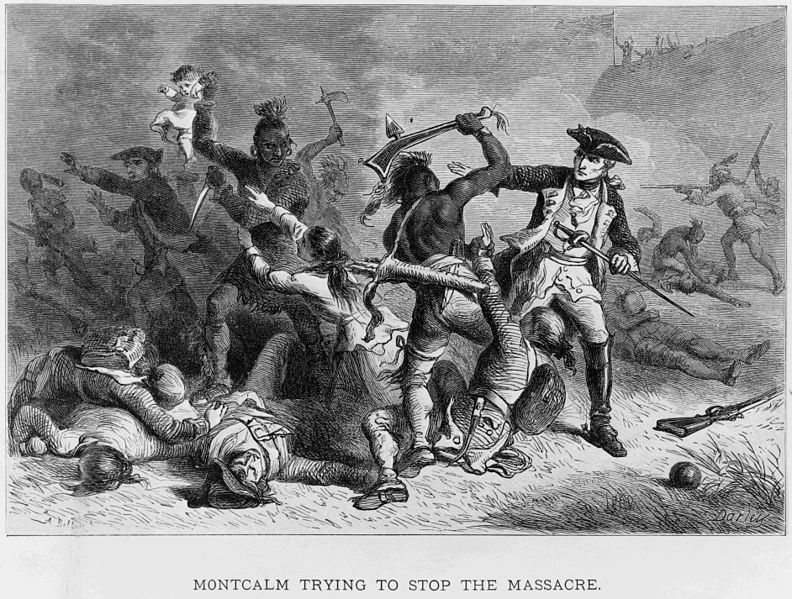

[The rest of Chapter 16 describes negotiations with French General Montcalm.

Munro agrees to surrender Fort William Henry to the superior forces of the

French and their Indian allies. The English forces may honorably relinquish the

fort by marching out with

their weapons unloaded.

![]()

from Chapter 17

[Chapter

17 opens with French General Montcalm (also a historic figure) meeting by

night with Magua, a leader among Indians opposing the English. Magua dislikes

letting the English keep their weapons, as these would normally be among the

spoils or loot claimed after a victory. This discontent sets up a massacre as

the English leave Fort William Henry.

[As in Mary Rowlandson’s Captivity Narrative, note how the enemy Indians are depicted in terms similar to current depictions of terrorists: uncivilized, hot-headed, willing to attack women and children]

[17.1] . .

. By this time the signal for departure

[from the fort]

had been given, and the head of the English column was in motion. The sisters

started at the sound, and glancing their eyes around, they saw the white

uniforms of the French grenadiers

[soldiers],

who had already taken possession of the gates of the fort. At that moment an

enormous cloud seemed to pass suddenly above their heads, and, looking upward,

they discovered that they stood beneath the wide folds of the standard

[flag]

of

[17.2]

"Let us go,” said Cora; "this is no longer a fit place for the children of an

English officer.”

[family + national honor]

[17.4]

As they passed the gates, the French officers, who had learned their rank

[officers = gentlemen],

bowed often and low, forbearing, however, to intrude those attentions which they

saw, with peculiar tact, might not be agreeable.

As every vehicle and each beast of

burden was occupied by the sick and wounded, Cora had decided to endure the

fatigues of a foot march, rather than interfere with their comforts. Indeed,

many a maimed and feeble soldier was compelled to drag his exhausted limbs in

the rear of the columns, for the want of the necessary means of conveyance in

that wilderness. The whole, however, was in motion; the weak and wounded,

groaning and in suffering; their comrades silent and sullen;

and the women and children in terror,

they knew not of what.

[again historical fiction or the historic romance refocuses from public/historic to personal/family]

[17.5]

As the confused and timid throng left the protecting mounds of the fort, and

issued on the open plain, the whole scene was at once presented

to their eyes. At a little distance on the right, and somewhat in the rear, the

French army stood to their arms,

Montcalm having collected his parties, so soon as his guards had possession of

the works. They were attentive but silent observers of the proceedings of the

vanquished, failing in none of the stipulated

military honors, and offering no

taunt or insult, in their success, to their less fortunate foes.

Living masses of the English, to the

amount, in the whole, of near three thousand, were moving slowly across the

plain, toward the common center, and gradually approached each other, as they

converged to the point of their march, a vista

[opening, prospect]

cut through the lofty trees, where the road to the Hudson entered the forest.

Along the sweeping borders of the woods hung

a dark cloud of savages, eyeing the

passage of their enemies, and hovering at a distance,

like vultures who were only kept

from swooping on their prey by the presence and restraint of a superior army.

A few

[French-allied Indians]

had straggled among the conquered columns, where they stalked in sullen

discontent; attentive, though, as yet, passive observers of the moving

multitude.

[17.6]

The advance

[army contingent at front of column],

with Heyward at its head, had already reached the defile [meeting point for path

of departure], and was slowly disappearing

[into forest],

when the attention of Cora was drawn to

a collection of stragglers by the sounds of contention. A truant provincial

[colonist trailing behind]

was paying the forfeit of his disobedience, by being plundered

[by the Indians]

of those very effects which had caused him to desert his place in the ranks. The

man was of powerful frame, and too avaricious

[greedy]

to part with his goods without a struggle.

Individuals from either party

interfered; the one side to prevent and the other to aid in the robbery. Voices

grew loud and angry, and a hundred savages appeared, as it were, by magic, where

a dozen only had been seen a minute before. It was then that

Cora saw the form of Magua gliding among

his countrymen, and speaking with his fatal and artful eloquence. The mass of

women and children stopped, and hovered together like alarmed and fluttering

birds. But the cupidity

[rapacity]

of the Indian

[plural reference to Indians plundering greedy white man]

was soon gratified, and the different bodies again moved slowly onward.

[17.7] The savages now fell back, and seemed content to let their

enemies advance without further molestation. But,

as the female crowd approached them, the

gaudy colors of a shawl attracted the eyes of a wild and untutored Huron. He

advanced to seize it without the least hesitation. The woman, more in terror

than through love of the ornament, wrapped her child in the coveted article, and

folded both more closely to her bosom. Cora was in the act of speaking, with an

intent to advise the woman to abandon the trifle, when the savage relinquished

his hold of the shawl, and tore the screaming infant from her arms.

Abandoning everything to the greedy grasp of those around her, the mother

darted, with distraction in her mien

[bearing, composure],

to reclaim her child. The Indian smiled grimly, and extended one hand, in sign

of a willingness to exchange, while, with the other, he flourished the babe over

his head, holding it by the feet as if to enhance the value of the ransom.

[17.8]

"Here—here—there—all—any—everything!” exclaimed the breathless woman, tearing

the lighter articles of dress from her person with ill-directed and trembling

fingers; "take all, but give me my babe!”

[17.9]

The savage spurned the worthless rags, and perceiving that the shawl had already

become a prize to another, his bantering but sullen smile changing to a gleam of

ferocity, he dashed the head of the infant against a rock, and cast its

quivering remains to her very feet. For an instant the mother stood, like a

statue of despair, looking wildly down at the unseemly object, which had so

lately nestled in her bosom and smiled in her face; and then she raised her eyes

and countenance toward heaven, as if calling on God to curse the perpetrator of

the foul deed.

She was spared the sin of such a prayer for, maddened at his disappointment, and

excited at the sight of blood, the Huron

mercifully drove his tomahawk into her own brain. The mother sank under the

blow, and fell,

grasping at her child, in death, with the same engrossing

love that had caused her to cherish it when living.

|

[17.10]

At that dangerous moment, Magua placed his hands to his mouth, and raised the

fatal and appalling whoop.

The scattered Indians started at the well-known cry, as coursers

[race-horses]

bound at the signal to quit the goal; and directly there

arose such a yell along the plain, and through

the arches of the wood

[wilderness gothic],

as seldom burst from human lips before. They who heard it listened with a

curdling horror at the heart, little inferior to that dread which may be

expected to attend the blasts of the final summons.

[sublime mix of terror and power]

[17.11]

More than two thousand raving savages broke from the forest at the signal, and

threw themselves across the fatal plain with instinctive alacrity

[eagerness].

We shall not dwell on the revolting horrors that succeeded. Death was

everywhere, and in his most terrific and disgusting aspects.

Resistance only served to inflame the murderers, who inflicted their furious

blows long after their victims were beyond the power of their resentment.

The flow of blood might be likened to

the outbreaking of a torrent; and as the natives became heated and maddened by

the sight, many among them even kneeled to the earth, and drank freely,

exultingly, hellishly, of the crimson tide.

[over-the-top gothic sensationalism depicts Indians as demons]

[17.12] The trained bodies of the troops threw themselves quickly

into solid masses, endeavoring to awe their assailants by the imposing

appearance of a military front. The experiment in some measure succeeded, though

far too many suffered their

unloaded

muskets to be torn from their hands, in the vain hope of appeasing the

savages.

|

|

[17.13] In such a scene none had leisure to note the fleeting

moments. It might have been ten minutes (it seemed an age) that

the sisters had stood riveted to one

spot, horror-stricken and nearly helpless. When the first blow was struck,

their screaming companions had pressed upon them in a body, rendering flight

impossible; and now that fear or death had scattered most, if not all, from

around them, they saw no avenue open, but such as conducted to the tomahawks of

their foes. On every side arose shrieks, groans, exhortations and curses. At

this moment,

[17.14] "Father—father—we are here!” shrieked

[17.15] The cry was repeated, and in terms and tones that might

have melted a heart of stone, but it was unanswered. Once, indeed, the old man

appeared to catch the sound, for he paused and listened; but

[17.16]

"Lady,” said Gamut

[the psalmist David],

who, helpless and useless as he was, had not yet dreamed of deserting his trust,

"it is the jubilee of the devils*,

and this is not a meet place for Christians to tarry in. Let us up and fly.”

[17.17]

"Go,” said Cora, still gazing at her unconscious sister; "save thyself. To me

thou canst not be of further use.”

[17.18] David comprehended the unyielding character of her

resolution, by the simple but expressive gesture that accompanied her words. He

gazed for a moment at

the dusky forms

that were acting their hellish rites on every side of him, and his tall

person grew more erect while his chest heaved, and every feature swelled, and

seemed to speak with the power of the feelings by which he was governed.

[17.19]

"If the Jewish boy*

might tame the great spirit of Saul by the sound of his harp, and the words of

sacred song, it may not be amiss,” he said, "to try the potency

[power]

of music here.”

[17.20]

Then raising his voice to its highest tone, he poured out a strain

[melody]

so powerful as to be heard even amid the din of that bloody field. More than one

savage rushed toward them, thinking to rifle

[rob]

the unprotected sisters of their attire, and bear away their scalps; but when

they found this strange and unmoved figure riveted to his post, they

[marauding Indians]

paused to listen. Astonishment soon changed to admiration,

and they passed on to other and less

courageous victims, openly expressing their satisfaction at the firmness with

which the white warrior sang his death song

[a ritual of Indian captives under torment].

Encouraged and deluded by his success, David exerted all his powers to extend

what he believed so holy an influence.

The unwonted

[unexpected]

sounds caught the ears of a distant savage,

who flew raging from group to group, like one who, scorning to touch the vulgar

herd, hunted for some victim more worthy of his renown. It was

Magua, who uttered a yell of pleasure

when he beheld his ancient prisoners again at his mercy.

[17.21] "Come,” he said,

laying his soiled hands on the dress of Cora, "the wigwam of the Huron is still

open. Is it not better than this place?”

[17.22]

"Away!” cried Cora, veiling her eyes from his revolting aspect.

[17.23] The Indian laughed tauntingly, as he

held up his reeking

[bloody]

hand, and answered: "It is red, but it comes from white veins!”

[blood = race]

[17.24]

"Monster! there is blood, oceans of blood, upon thy soul; thy spirit has moved

this scene.”

[17.25] "Magua is a great chief!” returned the exulting savage,

"will the

dark-hair go to his tribe?”

[17.26]

"Never! strike if thou wilt, and complete thy revenge.”

He hesitated a moment, and then catching the light and senseless form of

[17.27]

"Hold!” shrieked Cora, following wildly on his footsteps; "release the child!

wretch! what is't you do?”

[17.28]

But Magua was deaf to her voice; or, rather, he knew his power, and was

determined to maintain it.

[17.29]

"Stay—lady—stay,” called Gamut, after the unconscious Cora. "The holy charm is

beginning to be felt, and soon shalt thou see this horrid tumult stilled.”

[17.30] Perceiving that, in his turn, he was unheeded, the faithful

David followed the distracted sister, raising his voice again in sacred song,

and sweeping the air to the measure, with his long arm, in diligent

accompaniment.

In this manner they

traversed the plain, through the flying, the wounded and the dead. The

fierce Huron was, at any time, sufficient for himself and the victim that he

bore

[Magua carries off the unconscious Alice];

though Cora would have fallen more than

once under the blows of her savage enemies, but for the extraordinary being

[Gamut, still singing]

who stalked in her rear, and who now appeared to the astonished natives gifted

with the protecting spirit of madness.

[17.31]

Magua, who knew how to avoid the more pressing dangers, and also to elude

pursuit, entered the woods through a low ravine, where he quickly found the

Narragansetts

[the sisters’ horses],

which the travelers had abandoned so shortly before, awaiting his appearance, in

custody of a savage as fierce and malign in his expression as himself. Laying

[17.32] Notwithstanding the horror excited by the presence of her

captor, there was a present relief in escaping from the bloody scene enacting on

the plain, to which Cora could not be altogether insensible. She took her seat,

and held forth her arms for her sister, with

an air of entreaty and love that even

the Huron could not deny. Placing

[17.33] They soon began to ascend; but as the motion had a tendency

to revive the dormant faculties of her sister, the attention of Cora was too

much divided between the tenderest solicitude in her behalf, and in listening to

the cries which were still too audible on the plain, to note the direction in

which they journeyed. When, however, they gained the flattened surface of the

mountain-top, and approached the eastern precipice, she recognized the spot to

which she had once before been led under the more friendly auspices of the

scout. Here Magua suffered them to dismount; and notwithstanding their own

captivity, the curiosity which seems

inseparable from horror, induced them to gaze at the sickening sight below.

[spectacle]

[17.34]

The cruel work was still unchecked. On every side the captured were flying

before their relentless persecutors, while the armed columns of the Christian

king

[of France]

stood fast in an apathy

[immobility]

which

has never been explained, and which has left an immovable blot on the otherwise

fair escutcheon

[honor]

of their leader. Nor was the sword of death stayed until cupidity got the

mastery of revenge. Then, indeed, the shrieks of the wounded, and the yells of

their murderers grew less frequent, until, finally, the cries of horror were

lost to their ear, or were drowned in the loud, long and piercing whoops of the

triumphant savages.

End Chapter 17.

[Thus begins Cora’s and Alice’s second

captivity narrative,

which the final two thirds of the novel resolve.]

![]()

![]()