American

Romanticism:

Lecture notes

Lincoln, Stowe, Thoreau

| preview discussion questions review film noir & gothic light/dark midterm review Stowe, Thoreau, Lincoln [break] Mexican America assignments > lyric, obj. 1 poetry: Amy Sidle |

|

Romanticism & Abolition: The Slave Narrative

Thursday 16 October: Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, N 804-825. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life . . . , N 920-991.

text-objective discussion leader: Cory Owens

poetry: Robert Hayden, "Those Winter Sundays," N 2424

poetry reader / discussion leader: Telishia Mickens

web highlight (final exams): Larry Finn

Romanticism & Abolition, 2nd meeting

Thursday 23 October: Monday: Abraham Lincoln, N 732-36. Harriet Beecher Stowe, selections from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, N 764-799. Thoreau, N 825-844 (“Resistance to Civil Government”).

Backgrounds to Civil Disobedience

text-objective discussion leader: Rachel Zoch

poetry: Theodore Roethke, "I Knew a Woman," N 2323

poetry reader / discussion leader: Amy Sidle

Course Objectives

Objective 1: Literary Categories of Romanticism

-

To identify and criticize ideas or attitudes associated with Romanticism, such as desire and loss, rebellion, nostalgia, idealism, the gothic, the sublime, the individual in nature or separate from the masses.

-

Romance narrative: A desire for anything besides “the here and now” or “reality," the Romantic impulse, quest, or journey involves crossing physical borders or transgressing social or psychological boundaries in order to attain or regain some transcendent goal or dream.

-

A Romantic hero or heroine may appear empty or innocent of anything but readiness to change or yearning to re-invent the self or world--esp. the golden boy and fair lady; see also their counterparts, the dark lady and the Byronic hero

Objective

1b. The Romantic Period

-

To observe Romanticism’s co-emergence in the late 18th through the 19th centuries with the middle class, cities, industrial capitalism, consumer culture, & nationalism.

-

To observe predictive elements in “pre-Romantic” writings from earlier periods such as “The Seventeenth Century” and the "Age of Reason."

-

To speculate on residual elements in “post-Romantic” writings from later periods incl. “Realism and Local Color,” "Modernism," and “Postmodernism.”

Objective

1c: Romantic Genres

To describe & evaluate leading literary genres of Romanticism:

-

the romance narrative or novel (journey from repression to transcendence)

-

the gothic novel or style (haunted physical and mental spaces, the shadow of death or decay; dark and light in physical and moral terms; film noir)

-

the lyric poem (a momentary but comprehensive cognition or transcendent feeling—more prominent in European than American Romanticism?)

-

the essay (esp. for Transcendentalists—descended from the Puritan sermon?)

Objective 2: Cultural Issues:

America as Romanticism, and vice versa

2a. To identify the Romantic era in the United States of America as the “American Renaissance”—roughly the generation before the Civil War (c. 1820-1860, one generation after the Romantic era in Europe).

2b. To acknowledge the co-emergence and convergence of "America" and "Romanticism." European Romanticism begins near the time of the American Revolution, and Romanticism and the American nation develop ideas of individualism, sentimental nature, rebellion, and equality in parallel.

2c. Racially divided but historically related "Old and New Canons" of Romantic literature:

-

European-American: from Emerson’s Transcendentalism and Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age

-

African American: from the Slave Narratives of Douglass and Jacobs to the Harlem Renaissance of Hughes, Hurston, and Cullen

-

American Indian: conflicted Romantic icon in Cooper and Zitkala-Sa.

-

(Mexican American Literature is not yet incorporated into this course—seminar will discuss.)

2d. Economically liberal but culturally conservative, the USA creates "Old and New Canons" also in terms of gender

-

masculine traditions: freedom and the frontier (with variations)

-

feminine traditions: relations and domesticity (with variations

-

Also consider “Classical” and “Popular” literature as gendered divisions.

2e. American Romanticism exposes competing or complementary dimensions of the American identity: is America a culture of sensory and material gratification or moral, spiritual, idealistic mission?

2f. If "America" and "Romanticism" converge, to what degree does popular American culture and ideology—from Hollywood to human rights—represent a derivative form of classic Romanticism?

review film noir & gothic light/dark

last class ended with documentary on film noir--purpose: compare to gothic

femme fatale

light / dark

1d. “The Color Code”

-

Literature represents the extremely sensitive subject of skin color infrequently or indirectly.

-

Western civilization transfers values associated with “light and dark”—e. g., good & evil, rational / irrational—to people of light or dark complexions, with huge implications for power, validity, sexuality, etc.

-

This course mostly treats minorities as a historical phenomenon, but the biological or visual aspect of human identity may be more immediate and direct than history. People most comfortably interact with others who look like themselves or their family.

-

Skin color matters, but how much varies by circumstances.

-

See also Objective 3 on racial hybridity.

Norton Anthology, 931-2

The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave

by Frederick Douglass

(Boston, 1845)

CHAPTER I

I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvesttime, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twentyeight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

My mother was named Harriet Bailey. She was the daughter of Isaac and Betsey Bailey, both colored, and quite dark. My mother was of a darker complexion than either my grandmother or grandfather.

My father was a white man. He was admitted to be such by all I ever heard speak of my parentage. The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing; the means of knowing was withheld from me. My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant--before I knew her as my mother. It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. Frequently, before the child has reached its twelfth month, its mother is taken from it, and hired out on some farm a considerable distance off, and the child is placed under the care of an old woman, too old for field labor. For what this separation is done, I do not know, unless it be to hinder the development of the child's affection toward its mother, and to blunt and destroy the natural affection of the mother for the child. This is the inevitable result.

I never saw my mother, to know her as such, more than four or five times in my life; and each of these times was very short in duration, and at night. She was hired by a Mr. Stewart, who lived about twelve miles from my home. She made her journeys to see me in the night, travelling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of her day's work. She was a field hand, and a whipping is the penalty of not being in the field at sunrise, unless a slave has special permission from his or her master to the contrary--a permission which they seldom get, and one that gives to him that gives it the proud name of being a kind master. I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. Very little communication ever took place between us. Death soon ended what little we could have while she lived, and with it her hardships and suffering. She died when I was about seven years old, on one of my master's farms, near Lee's Mill. I was not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial. She was gone long before I knew any thing about it. Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.

Norton Anthology, 805-06

Boston 1861

I. Childhood

I was born a slave; but I never knew it till six years of happy childhood had

passed away. My father was a carpenter, and considered so intelligent and

skilful in his trade, that, when buildings out of the common line were to be

erected, he was sent for from long distances, to be head workman. On condition

of paying his mistress two hundred dollars a year, and supporting himself, he

was allowed to work at his trade, and manage his own affairs. His strongest wish

was to purchase his children; but, though he several times offered his hard

earnings for that purpose, he never succeeded.

In complexion my parents were a light shade of brownish yellow, and were termed mulattoes. They lived together in a comfortable home; and, though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise, trusted to them for safe keeping, and liable to be demanded of them at any moment. I had one brother, William, who was two years younger than myself--a bright, affectionate child.

I had also a great treasure in my maternal grandmother, who was a remarkable woman in many respects. She was the daughter of a planter in South Carolina, who, at his death, left her mother and his three children free, with money to go to St. Augustine, where they had relatives. It was during the Revolutionary War; and they were captured on their passage, carried back, and sold to different purchasers. . . .

She was much praised for her cooking; and her nice crackers became so famous in the neighborhood that many people were desirous of obtaining them. In consequence of numerous requests of this kind, she asked permission of her mistress to bake crackers at night, after all the household work was done; and she obtained leave to do it, provided she would clothe herself and her children from the profits. Upon these terms, after working hard all day for her mistress, she began her midnight bakings, assisted by her two oldest children. The business proved profitable; and each year she laid by a little, which was saved for a fund to purchase her children.

Her master died, and the property was divided among his heirs. The widow had her dower in the hotel which she continued to keep open. My grandmother remained in her service as a slave; but her children were divided among her master's children. As she had five, Benjamin, the youngest one, was sold, in order that each heir might have an equal portion of dollars and cents. There was so little difference in our ages that he seemed more like my brother than my uncle. He was a bright, handsome lad, nearly white; for he inherited the complexion my grandmother had derived from Anglo-Saxon ancestors. Though only ten years old, seven hundred and twenty dollars were paid for him.

His sale was a terrible blow to my grandmother . . .

If white is good and black is wrong, what if you're black?

The most common and familiar "universals" may be culturally determined--and changeable.

African American literature explores alternative forms

Previews "the Black Aesthetic"--"Black is Beautiful!"

some variations from light-dark value scheme

European-derived model:

white = goodness, purity; black = evil, decay

African model?

white = oppression? daytime hours as white man's time

darkness = night as people's time, family time; fertility?

midterm review

review conference at any time this semester or beyond

all good, competent writers

downside: teachers praise you, leave you alone . . . students keep doing what's worked before

only known solution: to aspire to next level, negotiate with the gatekeeper--test or trial that stretches abilities

> reinforce thematic organization (to build ideas further, move faster, think harder & more systematically)

+ learn finer points like punctuation, style, diction

written comments > dialogue

rewrites?--no precise policy

always welcome to send in another version for posting to web

Re-grading more nebulous--must confer and show progress

sometimes effort is only factored into final grade

But point is not to make a grade but to improve

Scheduling: communicate at will, I don't resent prompts and reminders

learn together

Stowe, Thoreau, Lincoln

All of today's "Romantic" texts are also political. What is the relation between Romanticism and politics or, more generally, literary movements and social movements?

Questions for Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin

For much of the 20c, Stowe was dismissed as "sentimental." Why? Can she be defended from the accusation, or can sentimentality be redefined as a positive value or technique?

Previously we've observed a line between Romanticism and sentimentality

Romanticism and Transcendentalism

Romanticism and Christianity

passive resistance in Stowe?

Mario Savio, leader of Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, California, 1964.

From obituary: "Mario Savio, Protest Leader Who Set a Style, Dies at 53," New York Times 8 Nov. 1996, C21.

. . . Mr. Savio is remembered for the words he spoke on Dec. 2, 1964, from Sproul Plaza in front of Berkeley's main administration building, to a large crowd of protesters, many of whom took part in a sit-in inside the building and a campus strike.

"There is a time," he said, "when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part; and you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and make it stop. And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all."

The police arrested 800 of the protesters in what was the largest mass arrest in California history.

The sit-in was the climax of three months of student disorders in reaction to the university's decision to limit the activities of civil rights and political groups on the campus. Students contended that the restrictions abridged their constitutional rights. . . .

At a news conference after the Dec. 2 action, Mr. Savio said it had been the most successful student strike in American history, with only 17 per cent or 18 percent fo the students attending classes.

After a demonstration two months earlier, Mr. Savio was accused of biting a police officer's left thigh,, "breaking the skin and causing bruises." . . . Mr. Savio . . . apologized afterward to the officer because, as he put it, they were "both working-class kids."

Wendy Lasser, "Speech with the Weight of Literature," New York Times Book Review, 15 Dec. 1996, 43.

[Mario Savio] brought an innocence to the world—a pure, ingenuous, trusting sense of righteousness and compassion—that the world was ill equipped to handle. Sometimes, even before he died, I would think of him as a sainted Dostoyevskyan fool, like Prince Myshkin in "The Idiot." . . . He did not set out to be a martyr, certainly, but he was willing to lose in the name of justice; there were more important things to him than winning. "We are moving right now in a direction which one could call creeping barbarism," he said in 1994. "But if we do not have the benefit of the belief that in the end we will win, then we have to be prepared on the basis of our moral insight to struggle even if we do not know that we are going to win."

He was gentle, even to those who behaved brutally, and he was decent, even when he was angry. In 1964, when he clambered up on a police car to protest the arrest of a fellow student, he took off his shoes first so he wouldn't damage the car.

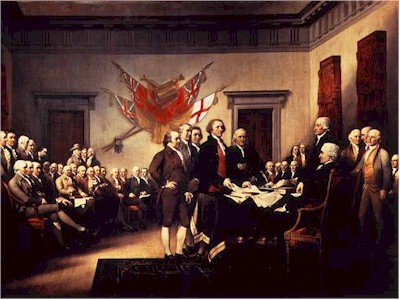

specific social problem: two generations after "All men are created equal," slavery grows and spreads

larger social problem: experiment of moral society in a political state in which religion is private, neither promoted nor discouraged by the state (issue is not just political but economic: capitalism defines good in terms of property and profits, not any higher spiritual good--though the concepts are not necessarily contradictory)

How to influence the American state morally?

civil disobedience backgrounds

Mexican America

2c. Racially divided but historically related "Old and New Canons" of Romantic literature:

-

European-American: from Emerson’s Transcendentalism and Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age

-

African American: from the Slave Narratives of Douglass and Jacobs to the Harlem Renaissance of Hughes, Hurston, and Cullen

-

American Indian: conflicted Romantic icon in Cooper and Zitkala-Sa.

-

(Mexican American Literature is not yet incorporated into this course—seminar will discuss.)

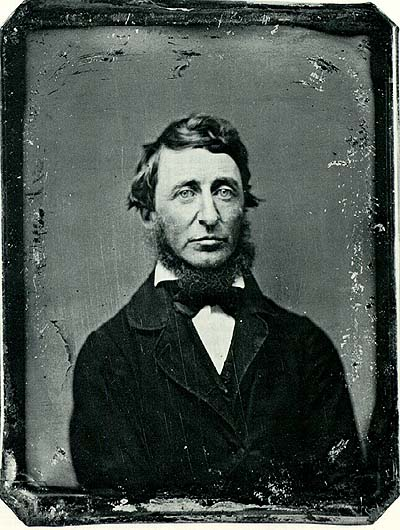

Thoreau

"the present Mexican war"

Texas Independence from Mexico > Republic of Texas 1836

Annexation of Texas to USA

U.S.-Mexican War or Mexican-American War 1846-48

In the U.S., the war is sometimes called the Mexican War. In Mexico, it is called la intervención norteamericana (the North American Intervention) or la guerra del 47 (the War of '47).

"Resistance to Civil Government" published 1849

historical maps of American expansion in early 1800s

Question whether new territories would be slave or free led directly to Civil War 15 years later.

Plus questions raised as to whether southwestern lands are properly Indian, Mexican, or USA--not just legal identity but who will inhabit them.

"cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico . . . "

Problems of including Mexico in early American literature:

1. geographical distance b/w Southwest and New England, where most American literature in English is concentrated.

2. language differences--most literature of Southwest from early 19th century appears as journalism in Spanish, or Anglo travelers' accounts

3. In New-World Catholic countries, literacy may be more concentrated in religious orders, not as widespread among common people.

Excuses! . . . It may take only a generation to change such orientations, attitudes, knowledge. By the time your age cohort is teaching a course like this, the course may look very different--as it now looks different from when I took similar courses.

Question of what literary instruction is for . . .

Knowledge of traditions?

Training in critical thinking and discussion?

Knowledge of traditions? > whose traditions?

What selection of texts? "People of color" or "great white fathers?"

Should our readings reflect the students in the classroom, or should all students be expected to read classic texts of the western tradition?

When teaching multicultural texts like Jacobs and Douglass, what methods, emphases, and lessons?

Should the difference be emphasized, or the places where they meet?

Specifically, should we read Douglass and Jacobs as . . .

examples of slave narratives, important foundation and expression of a distinct African American literary tradition?

or as examples of Romanticism?

assignments > lyric, obj. 1

Romanticism & Transcendentalism

Thursday 30 October: Ralph Waldo Emerson, N 488-97, 520-25, 532-37 (introduction & opening sections of Nature, The American Scholar, & Self-Reliance). (Try to finish at least one of these essays.) Margaret Fuller, N 736-47.

text-objective discussion leader: Kristin Hamon

poetry: Denise Levertov, "The Jacob's Ladder," N 2553

poetry reader / discussion leader: Dawlat Yassin

Romantic Free-Style: Whitman and descendents

Thursday 6 November: Walt Whitman, N 991-96, 1057-62 (“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), 1071-77 (“When Lilacs . . . “); “There Was a Child Went Forth“ (web post). Carl Sandburg, N 1987-90. Allen Ginsberg, N 2590-2602. Jack Kerouac, 2542-2551.

text-objective discussion leader: Matt Richards

poetry: Emily Dickinson, selected poems

poetry reader / discussion leader: volunteers to read poems and relate or contrast to objectives

Context for this class

Last week through next week

Peak period of American Romanticism as concurrent with "American Renaissance" or antebellum decades (i. e., before Civil War)

Period when literature and history blended--sometimes hard to know which you're talking about

Last week: American Renaissance as first great generation of African American writers, primarily writing "slave narratives"--literature inseparable from history of abolition

This week, two white literary activists in abolition movement plus American President most identified with end of slavery

In what ways is Douglass romantic?

slave narrative as quest

hero's desire to re-invent self, claim humanity and rights

Douglass is named after a character in a Sir Walter Scott poem

Some gothic characterizations: Mr. Gore, Mr. Severe (compare Jacobs on Dr. Flint as "demon in the pit")

What about Douglass diverges from Romanticism and/or turns more toward a distinct African American literature than toward mainstream western literature?

Their genre is first and foremost a slave narrative, not a romance. "Romance" is only useful for describing the form of the narrative--certainly not the content.

notes from last class, student discussion: "cracked hands," whippings, blood as reality of labor, pain, suffering--not romanticized but made real

Neither Douglass nor Jacobs have nostalgia for pastoral countryside

Jacobs 820

Douglass 946

> Harlem Renaissance associated with city, not countryside (compare American Renaissance)

Where might the two traditions meet and influence each other?

some variations from light-dark value scheme

European-derived model:

white = goodness, purity; black = evil, decay

African model?

white = oppression? daytime hours as white man's time

darkness = night as people's time, family time; fertility?

Some evidence of this in slave narratives, but keep in mind especially for Harlem Renaissance at end of semester.

Specific exercise:

Read a passage in Douglass, evaluate for both

P. 957 in anthology

“Sunday was my only leisure time. . . . My sufferings on the plantation seem now life a dream rather than a stern reality.

Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails . . . .

“You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave! . . . You are freedom’s swift-winged angels, that fly around the world; . . . O that I could also go! . . . If I could fly! . . . I will run away. . . . I had as well be killed running as die standing. . . It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom. . . . Meanwhile I will try to bear up under the yoke. I am not the only slave in the world. . . . It may be that my misery in slavery will only increase my happiness when I get free. There is a better day coming.”

What's Romantic about this passage?

What's African American?

What's Romantic?

individual against backdrop of nature--> Emerson, Edwards, others

transcendence

escape from here and now to future day

What's African-American?

"chains" aren't necessarily metaphorical

"the dream"--not necessarily achieved, but still a promise

"If I could fly!"--theme of "Flying Africans" in various African American texts like The People Could Fly, Song of Solomon, many others

Resolutions:

Literary study usually does not choose one voice to the exclusion of another

Instead, usually tries to "add voices"--potential problems with overloading, but potentially keeps voices in dialogue.

Therefore, the short answer is to read Douglass and Jacobs as "Romanticism" and "Multiculturalism," not to mention Feminism and other interests.

Irony: it's not a short answer . . . a semester's only so long, and students read less and less

Or they're reading differently, in different media

Methods of dialogue and discourse adapt us to change

digital / electronic media will take humanity into unimaginable territories

question whether same intellectual depth is possible as in print-reading

Model of history and literature together

966 more than Patrick Henry

1776: American Revolution for Independence

"all men are created equal"

> 1840s-60s: Abolition of slavery + early feminism--continuity or extension of American experiment in equality, literacy, and self-government

Discuss Stowe

Uncle Tom's Cabin as "great American novel?"--diverse ways of discussing its impact and qualities

1. politically, most powerful novel in history (not just in USA--influences also in Russia, Thailand--see Anna & the King of Siam)--Lincoln to Stowe: "So you're the little woman who started this big war?"

2. revolutionized publishing industry--greatest bestseller of its time, took advantage of "second" printing revolution (steam-driven industrial presses) and of increasing literacy rates in population

p. 772, bottom paragraph

Uncle Tom's Cabin & American Culture

3. major contribution of first great generation of educated urban women writers, particularly of "sentimental fiction"

the "other" American Renaissance--bestsellers mostly by women, mostly concerning courtship, family, surrogate families

compare Charlotte Temple 2 generations earlier

4. Stowe as member of great American evangelical-educational family, the Beechers

Harriet, Lyman, & Henry Ward Beecher

(contrast the Beechers' "hotter" evangelical Christianity with the Transcendentalists' "cooler" Unitarianism.)

5. Stowe as one of American literature's best writers of English

Background for discussion:

As Thoreau implies in "Resistance of Civil Government," most citizens of the northern United States got along with doing business with the slaveholding south, saw it as a status quo that they couldn't easily change, someone else's business--the usual rationalizations people make concerning injustice as long as they don't perceive themselves suffering from it.

Until westward expansion, most non-Southern Americans thought slavery would eventually decline and prove unprofitable, problem would be worked out by economic and social progress

1830s-40s: expansion of slavery into new Southern states like Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, Southwest territories taken from Mexico like Texas

1850: Fugitive Slave Law

1851-2: publication of Uncle Tom's Cabin, first in serial form, then as bestseller

1861-65: American Civil War

Question for discussion:

Based on your readings, how did Uncle Tom's Cabin turn Stowe into "the little woman who started this big war?"

Thoreau

|

|

|

problem of moral society in state separated from religion (not just political state, but economics of capitalism)

How to influence morally?

civil disobedience backgrounds

statue of Gandhi in Herman Park

assignments

1. Insofar as you understand Transcendentalism, how do Emerson's writings exemplify this movement or framework of thought? Compare, contrast Thoreau, Fuller.

2. How is Transcendentalism compatible with or distinct from Romanticism?

3. How does Fuller vary Emerson's Transcendentalism in a feminist direction?

Identifying Transcendentalism

as

a movement in American Renaissance Literature

The Web of American Transcendentalism (Virginia Commonwealth University)

Project in American Literature on Transcendentalism

Like Romanticism, “Transcendentalism” is a big, baggy word that can mean many different things. Overall it's not as big or enduring a concept as Romanticism--though it can be stretched and expanded.

In the simplest historical terms, Transcendentalism is a name for a loosely associated movement or group of intellectuals, writers, and religious or social leaders in New England in the 1830s-1850s who shared similar backgrounds, styles, and interests.

Most important figures: Emerson, Fuller, Thoreau

Next in importance: Bronson Alcott (father of Louisa May Alcott), Theodore Parker, Charles Ripley, Henry James Senior, Jones Very.

Sometimes other American Renaissance writers are included because of stylistic or thematic resemblances in their literature, plus some of this group were personally acquainted with the Transcendentalists.*

What these Transcendentalists had in common:

Pastors, members, or children of members of the Unitarian Church, in which Transcendentalism may be seen as a movement.

Emerson is at the center of the movement: most Transcendentalists were his friends or professional acquaintances.

History of the Unitarian Church:

17th century: Puritanism (Congregational

Church) >

late 18th century, early 19th

century: Congregationalism (Trinitarian) + Unitarian

1830s-1850s: Unitarianism > Transcendentalism

How do we get from Puritanism to Transcendentalism?

“Puritanism” is generally a bad word in modern discourse, and “hip” literary people usually shun Puritanism reflexively. But students of American literature and culture have to build a respectful relationship with the Puritans for the following reasons:

1. Puritans were highly literate people. If you’re a student of early American literature and culture, New England has far more records and texts to study than any other part of the USA. New England has continued to produce the most important writers to American literature. (Beyond the American Renaissance, think Robert Frost, e e cummings, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bishop, Thomas Pynchon.)

2. If most literary people are less than gung-ho about America’s possible image as an aggressively capitalist, imperialist nation, New England is among the only parts of the country founded for reasons other than economic opportunity a consistent home for movements involving Abolition of slavery, Women’s Rights, Pacifism, religious tolerance, and environmentalism.

How did the Puritans turn into “Yankee Liberals?”

Puritanism in New England. A “hot” church or religious movement “cools off.”

17th century: Puritanism as part of Protestant Reformation. Boston as the “City on a Hill,” the “City of God” > Salem Witch Trials

18th century: Enlightenment, Age of Reason. As education spreads, the western world opens to increasing knowledge of other religions besides Christianity and regret over excesses of religious behavior (e. g., Salem Witch Trials). “Unitarianism” appears as an attempt to recognize the “unity” of God throughout nature and the world and to “rationalize” religious behavior (e. g., to improve ethics and social justice rather than prepare for the hereafter).

Historical Note: Unitarianism is never a large, mass movement; its influence derives from social prestige and intellectual depth. At the same time that Unitarianism is emerging as a “cool” religion, “hot” religions such as Methodism, Baptistry, Mormonism, the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Seventh-Day Adventists are starting to bubble up all over the country. (“Hot” religions tend to emphasize individual salvation and the wellbeing of their religious community; “cool” religions tend to emphasize social justice on a larger scale.)

Peak period of Unitarianism: late 1700s, early 1800s.

Emergence of Transcendentalism: 1830s-50s.

Is Transcendentalism a religion? Obviously some religious

themes, but never organized enough institutionally to become a religion of its

own. You could call it a religious movement, but not a religion.

Why can public schools study Transcendentalism and not Baptistry or Mormonism?

*literary prestige

*”universality” of religious themes and images—its range of reference isn’t restricted to one religion

*no conversion motive: rather than draw a person to a particular way of thinking, Transcendentalism seeks for each individual to come to terms with whatever’s at work inside.

*Why religious conservatives can still gripe:

Transcendentalism can sound like “New Age” thinking in its imagery of

self-liberation and its diverse religious traditions—though New Age writing

tends to be much lazier. Also, Unitarianism and Transcendentalism can be said to

resemble “secular humanism” in terms of de-emphasizing a supreme divine

authority beyond the human realm.

Genres: mostly non-fiction and poetry. Non-fiction may extend from Emerson’s essays to Thoreau’s intellectual memoirs to Fuller’s blend of essay and autobiography to sermons by Transcendentalist pastors.

Sometimes other American Renaissance writers are

included because of stylistic or thematic resemblances in their literature,

plus some of this group were personally acquainted with the Transcendentalists.*

*Whitman is the most frequent inclusion. His reading of

Emerson was essential to his intellectual growth (“I was simmering, simmering,

simmering . . . . Emerson brought me to a boil.”). When Whitman mailed Emerson

a first edition of Leaves of Grass,

Emerson wrote him back: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

Emerson’s essay “The Poet” appears to anticipate the changes Whitman makes

in American poetry.

*Hawthorne and Melville are sometimes categorized as

“Dark Transcendentalists” (compared to Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman as

“Light Transcendentalists”). Hawthorne knew Emerson and lived in Concord

(home of Emerson and Thoreau), and some of Hawthorne’s and Melville’s

symbols and themes may resemble those of Transcendentalism. But he and Melville

were more critical than supportive of Transcendentalism, and they primarily

wrote fiction rather than the genres associated with Transcendentalism.

*Occasionally, listings will include American Renaissance writers as diverse as Emily Dickinson and Frederick Douglass among the Transcendentalists. Doubtless these authors read Emerson and other Transcendentalists, and some resemblances can be found between their patterns of thought and imagery and those of the Transcendentalists. But in such applications “Transcendentalism” becomes so broad that the term loses any historical specificity and begins to blur differences for the sake of emphasizing unity—which sounds like what the Transcendentalists were often about!

textual form of Transcendentalism

"Transcendence"--compare action at end of romance narrative

The conclusion of a romance narrative is typically “transcendence”—“getting away from it all” or “rising above it all.” The characters “live happily ever after” or “ride off into the sunset” or “fly away” from the scenes of their difficulties (in contrast with tragedy’s social engagement or comedy’s restored unity).

Thoreau 847 "a higher law"

851 a point of view a little higher

852 higher sources

852 the individual as a higher and independent power

civil disobedience backgrounds

Abraham Lincoln, N 757-760.

What's Romantic, or not, about Lincoln? (both his life and his writing)

What comparisons to Douglass?

"new birth of freedom"