American Renaissance & American Romanticism:

The Byronic Hero

The Byronic hero is a fictional and cultural character type popular in the Romantic era and beyond. This character may appear in fiction, poetry, or history.

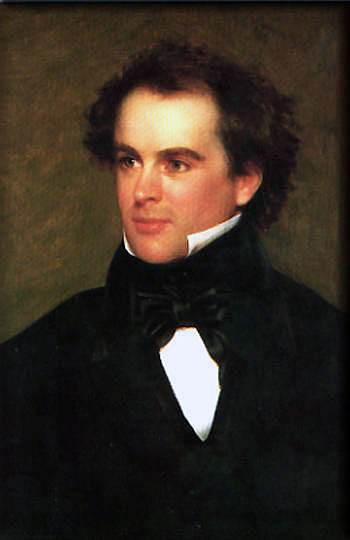

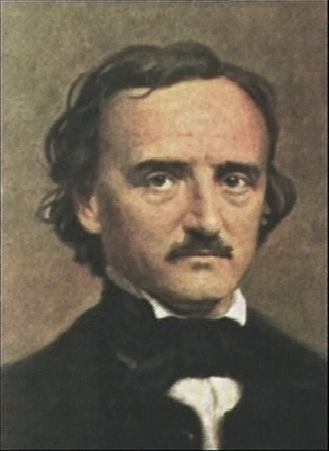

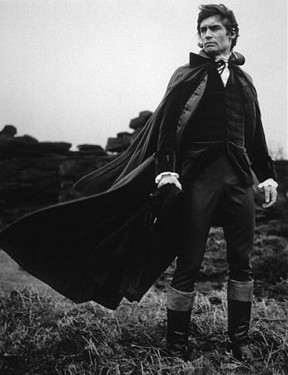

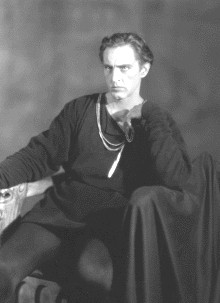

The term derives from the brilliant but scandalous English poet Lord Byron (1788-1824).

contemporary portraits of Byron

|

|

|

|

Qualities associated with the Byronic Hero:

dark, handsome appearance; brilliant but cynical and self-destructive

"wandering," searching behavior

haunted by some secret sin or crime, sometimes hints of forbidden love

modern culture hero: appeals to society by standing apart from society, superior yet wounded or unrewarded

fictional examples in American literature: Magua in Last of the Mohicans, Claggart in Billy Budd

Byronic authors in American literature: Poe,

|

|

|

Literary Development and Gender Variations:

As with the "fair lady-dark lady" tradition of literature, the dark Byronic hero is sometimes paired a more innocent, unmarked, even angelic figure.

For instance, the "dangerous" Byron was friends with the poet Shelley, who is often pictured as an angelic "Arial."

In Last of the Mohicans, the Byronic Magua opposes the princely Uncas.

In Jane Eyre (1847) by Charlotte Bronte, Jane must choose between the Byronic Rochester and the saintly St.-John Rivers.

In Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Bronte, Cathy chooses between the Byronic Heathcliff and the pleasant Edgar Linton.

|

|

|

Gender: The "Byronic" description is typically reserved for male characters; a corresponding woman character may fit the dark end of the "fair lady-dark lady" character structure.

In American Romantic literature, two woman nominees for Byronic traits may include the fictional character Cora in Cooper's Last of the Mohicans and the historical author Margaret Fuller (1810-1850).

|

|

|

Other literary examples of the Byronic hero:

Russian Literature:

| Alexander Pushkin, Eugene Onegin (1825-32) |

|

|

|

|

The Byronic Hero may be partly anticipated by Shakespeare's Hamlet (1601)

contemporary examples:

James Dean

Trent Reznor

Brandon Lee in The Crow

Layne Staley of Alice in Chains

Alan Rickman

Sean Connery

Sting

Tupac Shakur

Rufus Sewell in Dark City

LeStat in The Vampire Chronicles

Question:

How does the Byronic hero relate to Romanticism, historically and stylistically?

What is the significance of the Byronic hero as a "culture hero?"

Why does the paradigm, image, or symbol continue to recur and / or evolve?

What's ironical about the significance?

significance: culture hero who is dangerous to the culture for which he is a hero

Course Objectives

Objective 1: Literary Categories of Romanticism

-

To identify and criticize ideas or attitudes associated with Romanticism, such as desire and loss, rebellion, nostalgia, idealism, the gothic, the sublime, the individual in nature or separate from the masses.

-

Romance narrative: A desire for anything besides “the here and now” or “reality," the Romantic impulse, quest, or journey involves crossing physical borders or transgressing social or psychological boundaries in order to attain or regain some transcendent goal or dream.

-

A Romantic hero or heroine may appear empty or innocent of anything but readiness to change or yearning to re-invent the self or world.

Objective

1b. The Romantic Period

-

To observe Romanticism’s co-emergence in the late 18th through the 19th centuries with the middle class, cities, industrial capitalism, consumer culture, & nationalism.

-

To observe predictive elements in “pre-Romantic” writings from earlier periods such as “The Seventeenth Century” and the "Age of Reason."

-

To speculate on residual elements in “post-Romantic” writings from later periods incl. “Realism and Local Color,” "Modernism," and “Postmodernism.”

Objective

1c: Romantic Genres

To describe & evaluate leading literary genres of Romanticism:

-

the romance narrative or novel (journey from repression to transcendence)

-

the gothic novel or style (haunted physical and mental spaces, the shadow of death or decay; dark and light in physical and moral terms; film noir)

-

the lyric poem (a momentary but comprehensive cognition or transcendent feeling—more prominent in European than American Romanticism?)

-

the essay (esp. for Transcendentalists—descended from the Puritan sermon?)

Objective 2: Cultural Issues:

America as Romanticism, and vice versa

2a. To identify the Romantic era in the United States of America as the “American Renaissance”—roughly the generation before the Civil War (c. 1820-1860, one generation after the Romantic era in Europe).

2b. To acknowledge the co-emergence and convergence of "America" and "Romanticism." European Romanticism begins near the time of the American Revolution, and Romanticism and the American nation develop ideas of individualism, sentimental nature, rebellion, and equality in parallel.

2c. Racially divided but historically related "Old and New Canons" of Romantic literature:

-

European-American: from Emerson’s Transcendentalism and Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age

-

African American: from the Slave Narratives of Douglass and Jacobs to the Harlem Renaissance of Hughes, Hurston, and Cullen

-

American Indian: conflicted Romantic icon in Cooper and Zitkala-Sa.

-

(Mexican American Literature is not yet incorporated into this course—seminar will discuss.)

2d. Economically liberal but culturally conservative, the USA creates "Old and New Canons" also in terms of gender

-

masculine traditions: freedom and the frontier (with variations)

-

feminine traditions: relations and domesticity (with variations

-

Also consider “Classical” and “Popular” literature as gendered divisions.

2e. American Romanticism exposes competing or complementary dimensions of the American identity: is America a culture of sensory and material gratification or moral, spiritual, idealistic mission?

2f. If "America" and "Romanticism" converge, to what degree does popular American culture and ideology—from Hollywood to human rights—represent a derivative form of classic Romanticism?