American

Romanticism:

Lecture notes

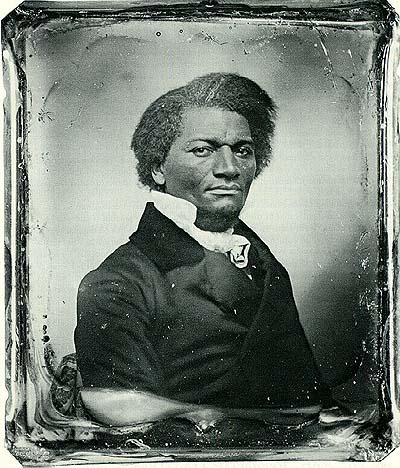

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life . . . ; Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

|

|

announcements, midterms, research, final web highlight: Larry Douglass, Jacobs discussion: Cory Owen [break] poetry: Tee Mickens Film Noir |

|

Romanticism & Abolition: The Slave Narrative

Thursday 16 October: Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, N 804-825. Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life . . . , N 920-991.

text-objective discussion leader: Cory Owens

poetry: Robert Hayden, "Those Winter Sundays," N 2424

poetry reader / discussion leader: Telishia Mickens

web highlight (final exams): Larry Finn

Course Objectives

Objective 1: Literary Categories of Romanticism

-

To identify and criticize ideas or attitudes associated with Romanticism, such as desire and loss, rebellion, nostalgia, idealism, the gothic, the sublime, the individual in nature or separate from the masses.

-

Romance narrative: A desire for anything besides “the here and now” or “reality," the Romantic impulse, quest, or journey involves crossing physical borders or transgressing social or psychological boundaries in order to attain or regain some transcendent goal or dream.

-

A Romantic hero or heroine may appear empty or innocent of anything but readiness to change or yearning to re-invent the self or world--esp. the golden boy and fair lady; see also their counterparts, the dark lady and the Byronic hero

Objective

1b. The Romantic Period

-

To observe Romanticism’s co-emergence in the late 18th through the 19th centuries with the middle class, cities, industrial capitalism, consumer culture, & nationalism.

-

To observe predictive elements in “pre-Romantic” writings from earlier periods such as “The Seventeenth Century” and the "Age of Reason."

-

To speculate on residual elements in “post-Romantic” writings from later periods incl. “Realism and Local Color,” "Modernism," and “Postmodernism.”

Objective

1c: Romantic Genres

To describe & evaluate leading literary genres of Romanticism:

-

the romance narrative or novel (journey from repression to transcendence)

-

the gothic novel or style (haunted physical and mental spaces, the shadow of death or decay; dark and light in physical and moral terms; film noir)

-

the lyric poem (a momentary but comprehensive cognition or transcendent feeling—more prominent in European than American Romanticism?)

-

the essay (esp. for Transcendentalists—descended from the Puritan sermon?)

Objective 2: Cultural Issues:

America as Romanticism, and vice versa

2a. To identify the Romantic era in the United States of America as the “American Renaissance”—roughly the generation before the Civil War (c. 1820-1860, one generation after the Romantic era in Europe).

2b. To acknowledge the co-emergence and convergence of "America" and "Romanticism." European Romanticism begins near the time of the American Revolution, and Romanticism and the American nation develop ideas of individualism, sentimental nature, rebellion, and equality in parallel.

2c. Racially divided but historically related "Old and New Canons" of Romantic literature:

-

European-American: from Emerson’s Transcendentalism and Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age

-

African American: from the Slave Narratives of Douglass and Jacobs to the Harlem Renaissance of Hughes, Hurston, and Cullen

-

American Indian: conflicted Romantic icon in Cooper and Zitkala-Sa.

-

(Mexican American Literature is not yet incorporated into this course—seminar will discuss.)

2d. Economically liberal but culturally conservative, the USA creates "Old and New Canons" also in terms of gender

-

masculine traditions: freedom and the frontier (with variations)

-

feminine traditions: relations and domesticity (with variations

-

Also consider “Classical” and “Popular” literature as gendered divisions.

2e. American Romanticism exposes competing or complementary dimensions of the American identity: is America a culture of sensory and material gratification or moral, spiritual, idealistic mission?

2f. If "America" and "Romanticism" converge, to what degree does popular American culture and ideology—from Hollywood to human rights—represent a derivative form of classic Romanticism?

announcements, midterms, research, final

WELCOME

NEW LITERATURE GRADUATE STUDENTS!

WELCOME BACK

RETURNING LITERATURE GRADUATE STUDENTS!

YOU’RE INVITED

TO A PARTY!

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 18, 7-10

Bring a guest, if you wish.

At the home of:

Peter and Gretchen Mieszkowski

4023 Manorfield Dr.

Seabrook, TX 77586

281-474-3836

Featuring:

Get-to-know-each-other party games

Refreshments

Desserts by Drs. Diepenbrock and Klett

Questions for discussion:

Can historical texts concerning social movements also be Romantic?

At what points do Romanticism and realism conflict or overlap?

In what ways does the Slave Narrative resemble a romance narrative?

Additional questions:

In what ways are Douglass & Jacobs Romantic?

What about Douglass or Jacobs turns more toward a distinct African American literature than toward mainstream western literature?

Assignments

Romanticism & Abolition, 2nd meeting

Backgrounds to Civil Disobedience

Thursday 23 October: Monday: Abraham Lincoln, N 732-36. Harriet Beecher Stowe, selections from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, N 764-799. Thoreau, N 825-844 (“Resistance to Civil Government”).

text-objective discussion leader: Rachel Zoch

poetry: Theodore Roethke, "I Knew a Woman," N 2323

poetry reader / discussion leader: Amy Sidle

specific social problem: two generations after "All men are created equal," slavery grows and spreads

larger social problem: experiment of moral society in a political state in which religion is private, neither promoted nor discouraged by the state (issue is not just political but economic: capitalism defines good in terms of property and profits, not any higher spiritual good--though the concepts are not necessarily contradictory)

How to influence the American state morally?

civil disobedience backgrounds

At what points do Romanticism and realism conflict or overlap?

In what ways does the Slave Narrative resemble a romance narrative?

Additional questions:

In what ways are Douglass & Jacobs Romantic?

What about Douglass or Jacobs turns more toward a distinct African American literature than toward mainstream western literature?

At what points do Romanticism and realism conflict or overlap?

In what ways does the Slave Narrative resemble a romance narrative?

Physical movement from North to South

Status movement from slavery to freedom

949 Abolition

975 but . . .

p. 959

“Sunday was my only leisure time. . . . My sufferings on the plantation seem now life a dream rather than a stern reality.

Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails . . . .

“You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave! . . . You are freedom’s swift-winged angels, that fly around the world; . . . O that I could also go! . . . If I could fly! . . . I will run away. . . . I had as well be killed running as die standing. . . It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water. This very bay shall yet bear me into freedom. . . . Meanwhile I will try to bear up under the yoke. I am not the only slave in the world. . . . It may be that my misery in slavery will only increase my happiness when I get free. There is a better day coming.”

What's Romantic about this passage?

What's African American?

What's Romantic?

individual against backdrop of nature--> Emerson, Edwards, others

transcendence (> Transcendentalism)

escape from here and now to future day

What's African-American?

"chains" aren't necessarily metaphorical

"the dream"--not necessarily achieved, but still a promise

From "Minority Literature" courses

Objective 1: Minority Definitions

American minorities are defined not by numbers but by power relations modeled on ethnic groups’ problematic relation to the American dominant culture.

1a. Involuntary participation and continuing oppression—the American Nightmare

Unlike the dominant immigrant culture, ethnic minorities did not choose to come to America or join its dominant culture. (African Americans were kidnapped, American Indians were invaded.)

. . .

1d. “The Color Code”

-

Literature represents the extremely sensitive subject of skin color infrequently or indirectly.

-

Western civilization transfers values associated with “light and dark”—e. g., good & evil, rational / irrational—to people of light or dark complexions, with huge implications for power, validity, sexuality, etc.

-

This course mostly treats minorities as a historical phenomenon, but the biological or visual aspect of human identity may be more immediate and direct than history. People most comfortably interact with others who look like themselves or their family.

-

Skin color matters, but how much varies by circumstances.

-

See also Objective 3 on racial hybridity.

p. 817

some variations from light-dark value scheme

European-derived model:

white = goodness, purity; black = evil, decay

African model?

white = oppression? daytime hours as white man's time

darkness = night as people's time, family time; fertility?

Some evidence of this in slave narratives, but keep in mind especially for Harlem Renaissance at end of semester.

Douglass pp 931-2

Leftover notes from previous classes

(From LITR 5535 2005)

web-highlight(s)

from previous semesters’ research projects: Matt Mayo

Prior to this class, I was completely

unfamiliar with the term Byronic Hero. As we discussed the term in class, I began to realize that

many of the “common” heroes of today, at least partially, fit our

definition. Our example of Magua,

from The Last of the Mohicans, presented a fairly good prototype. Other

characters such as Batman or William Wallace, from the movie Braveheart, also

spring to mind when discussing this topic. These characters present the full

range of human emotion. By

displaying their darkness and depth, we can more readily identify with them.

By way of contrast, heroes with purely good characteristics, or

one-dimensional heroes, are becoming more difficult to find.

In this genre, one of the first heroes to come to mind is Superman. Superman never shows us a dark or brooding side of his

character. For this hero, there is

a clear line between right and wrong, or good and evil.

As a result, we are given very little to work with in the way of depth

for the character. His background

is fairly well flushed out, yet Superman is very flat when compared to more

fully developed heroes, such as Jean Valjean from Les Miserables.

Subject

Headings:

What

is a Byronic Hero?

Was

Byron’s life Romantic?

Student

Paper & Internet Review

Conclusion

After completing my research, I feel I have a

better understanding of what goes into the making of a Byronic hero.

The characteristics and traits are clearly linked to the Romantic genre

of writing. Additionally, I have a greater appreciation of how Byron's

life and personality caused the development of a new literary term.

Throughout my research, I found myself trying

to identify Byronic heroes from literature or recent movies.

While going through this process, I found myself repeatedly bumping into

the standard American success storyline. Often,

a heroic character must overcome some sort of early trauma or difficulty in

order to transcend in to something greater for the betterment of others.

In this instance, the hero may have some Byronic qualities, but

ultimately falls short of being a complete Byronic hero…

Nature

in American Literature and Poetry

Introduction

Nature, particularly “an uncultivated or wild

area…or a countryside,” provides colors, expression, life, and beauty

(Oxford 968). Even the idea of

wilderness, with all of its innate beauty, inspires many people, both

artistically and philosophically. For

some, beauty and nature can cause moments of ecstasy, where they are

aesthetically lifted to another plane of consciousness.

John Miller, in his essay, “Beauty: A Path to Ecstasy,” explains:

Beauty

can lead us from the mundane to the sublime.

The beauty of Nature awakens in us the love of beauty; and if we respond

deeply, we may experience moments of ecstasy.

Beauty [and Nature] inspire the arts, whose very creative process may

occasion ecstasy. These experiences

reveal that love and bliss form the essence of our own nature.

(Abstract)

A beautiful sight in nature evokes unexplainable

emotions and feelings within a person. This

poses the question, “How can a person possibly describe these feelings brought

about by nature?” The following

journal is an attempt to understand this question through: a better

understanding of aesthetics, a survey of American authors and poets whom often

use nature in their works, and research of the differences in Nature writing

among authors of Romantic fiction, transcendentalists, and poets of the late

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Aesthetics?

Survey of Authors

Conclusion

Conclusion

Nature

can easily be considered a universal bond between human beings, in that any

person can, if they choose, experience it.

This journal only provides a starting point for research into theories

relating beauty and the environment and the way they are perceived by people.

Literature seems to be a reliable canvas for nature, as seen through the

works of Cooper, Emerson, Dickinson, Frost, and Cummings; however, other forms

of art might also express the aesthetic effects of beauty.

Further research may lead to the illustration of nature by Impressionist

painters, such as Monet, or to various musicians and their works.