American

Romanticism:

Lecture notes

Thursday 6 November: Walt Whitman, N 991-96, 1057-62 (“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), 1071-77 (“When Lilacs . . . “); “There Was a Child Went Forth“ (web post). Carl Sandburg, N 1987-90. Allen Ginsberg, N 2590-2602. Jack Kerouac, 2542-2551.

|

|

assignments,

final exam Whitman intro discussion: Matt Sandburg, Ginsberg, Kerouac [break] poetry: Dickinson poems |

|

Thursday 6 November: Walt Whitman, N 991-96, 1057-62 (“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”), 1071-77 (“When Lilacs . . . “); “There Was a Child Went Forth“ (web post). Carl Sandburg, N 1987-90. Allen Ginsberg, N 2590-2602. Jack Kerouac, 2542-2551; Thomas Wolfe, The Lost Boy (web post)

text-objective discussion leader: Matt Richards

poetry: Emily Dickinson, selected poems

poetry reader / discussion leader: volunteers to read poems and relate or contrast to objectives

Thomas Wolfe, The Lost Boy (web post) (1937)

(final paragraph)

And he knew that he would never come again, and that lost magic would not come again. Lost now was all of it--the street, the heat, King's Highway, and Tom the Piper's son, all mixed in with the vast and drowsy murmur of the Fair, and with the sense of absence in the afternoon, and the house that waited, and the child that dreamed. And out of the enchanted wood, that thicket of man's memory, Eugene knew that the dark eye and the quiet face of his friend and brother--poor child, life's stranger, and life's exile, lost like all of us, a cipher in blind mazes, long ago--the lost boy was gone forever, and would not return.

Assignments

Review course progress

Pre-Romantic > Romantic > post-Romantic

Survivals or revivals of Romantic style in later literary periods; participation in style by Native American and African American writers

Final 3 class meetings concern periods or movements after Romanticism / American Renaissance

next week: Realism (esp. "Psychological Realism"--Henry James and Edith Wharton)

following week: Local Color / Regionalism

final week: Harlem Renaissance / Modernism

Post-Romanticism: High Realism

Thursday 13 November: Henry James, N 1491-1532 (Daisy Miller: A Study)

text-objective discussion leader: Katie Breaux

poetry: Elizabeth Bishop, “The Fish,” N 2399

poetry reader / discussion leader: Kristin Hamon

web highlight (final exams ): Telishia Mickens

James (1843-1916) normally associated with "Realism," dominant American literary style after American Renaissance and Romantic era.

What traces of Romanticism remain?

What happens instead of Romanticism?

How essential is some element of Romanticism or romance for reader interest? (Daisy Miller was James's most popular story.)

Post-Romanticism: Harlem Renaissance & Jazz Age

Thursday 20 November:

Harlem Renaissance: Claude McKay, N 2-2086. Zora Neal Hurston, N 2157-61. Jean Toomer, N 2179-84. Langston Hughes N 2263-68. Countee Cullen, N 2283-87 + "From the Dark Tower" & "For a Poet" (web posts)

text-objective discussion leader (Harlem Renaissance): Ayme Christian

Jazz Age: F. Scott Fitzgerald, N 2184-2201 (“Winter Dreams”)

text-objective discussion leader (Fitzgerald): Laurie Forshage

Thursday 4 December: Final exam. Students may take final exam in-class or by email.

LITR 5536 American Realism syllabus

Whitman breaks out during Romantic era, many Romantic tendencies; but also some Realistic tendencies.

Broad question: What Romantic and Realistic styles or subjects appear in Whitman, and how does he resolve these different impulses or interests?

opportunity to refresh: How is Whitman's poetry still poetry, despite absence of formal mechanisms? What formal mechanisms remain? How does an "American style" of poetry result?

Sandberg and Ginsberg: peruse briefly for sake of continuity, influence of Whitman

Wolfe: how may prose style reflect Whitman's poetic style? What other Romantic features?

parallelism (+ anaphora)

Question: how or in what respects may Whitman's style or subject be considered either Romantic or Realistic?

Question: how does Whitman's revolution in style accommodate or complement his revolution in subject matter?

Wolfe

Questions:

In what ways is Wolfe obviously continuing to express a Romantic sensibility in the early 20th century?

How does Wolfe's prose style imitate Whitman's poetic style?

Wolfe writes at same time as Fitzgerald--Why has Fitzgerald survived while Wolfe has faded?

Wolfe 1900-1938 (Four major novels: Look Homeward, Angel [1929); Of Time and the River [1935]; The Web and the Rock [1939]; You Can't Go Home Again [1940])

Fitzgerald 1896-1940 (Four major novels: This Side of Paradise [1920]; The Beautiful and the Damned [1922]; The Great Gatsby [1925]; Tender is the Night [1934])

Both also wrote numerous short stories . . .

Possible to work in Hemingway to comparison? Especially Nick Adams stories?

Recall that Faulkner, other great fiction writer of period, appeared in class meeting on Poe.

(Short answer: Fitzgerald's a better writer, but what standards are being used to make that judgment?)

Instructor's notes:

In what ways is Wolfe obviously continuing to express a Romantic sensibility in the early 20th century?

Childhood

Loss + idealization of absence (>desire)

cycle of desire and loss (cf. Poe in "Ligeia")

industrialization as antagonist of Romantic nature or world

disappearance of lost vision into natural world / childhood

Does Romanticism blur all objects of desire together? Nature, childhood, beautiful youth (Uncas, brother, Ligeia), the past . . . .

How does Wolfe's prose style imitate Whitman's poetic style?

Use of "long line"

Attempt to capture copious and elusive reality—1689

Inclusion of common materials of everyday life

Use of long line enables (somewhat) the other two

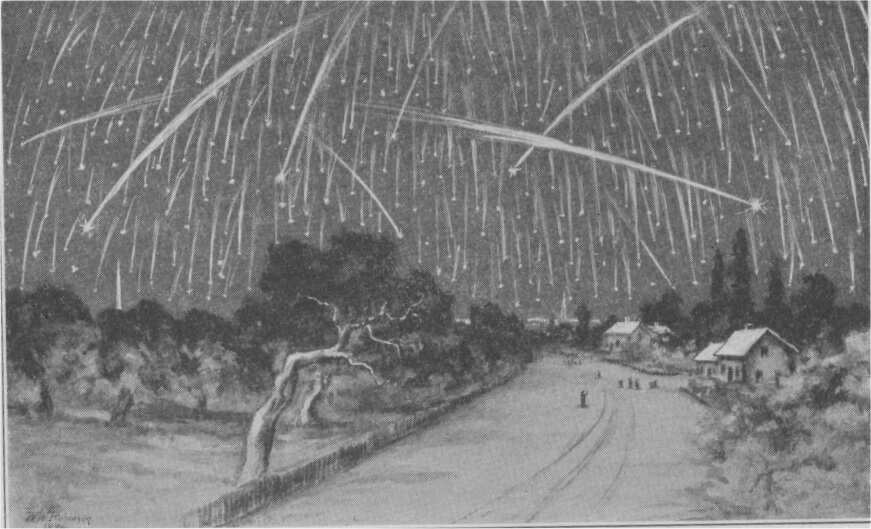

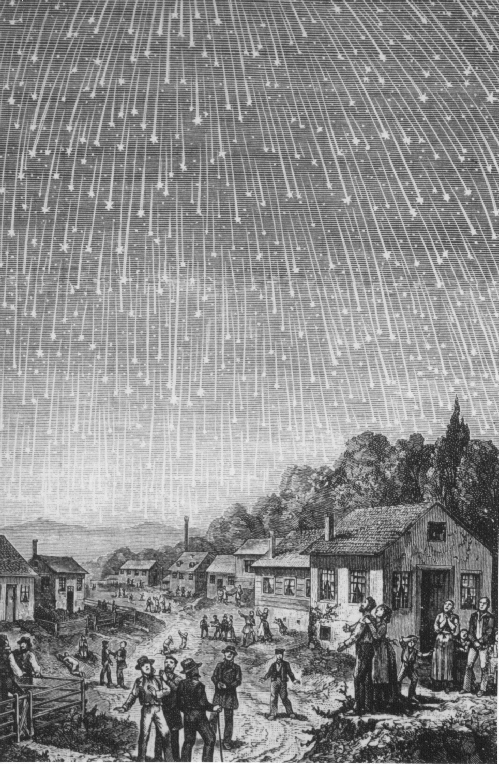

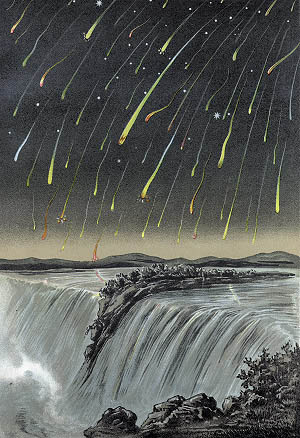

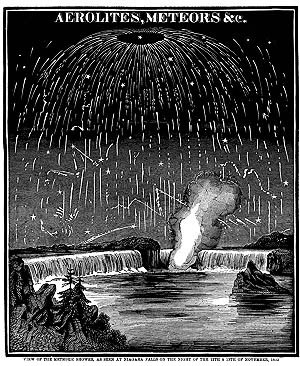

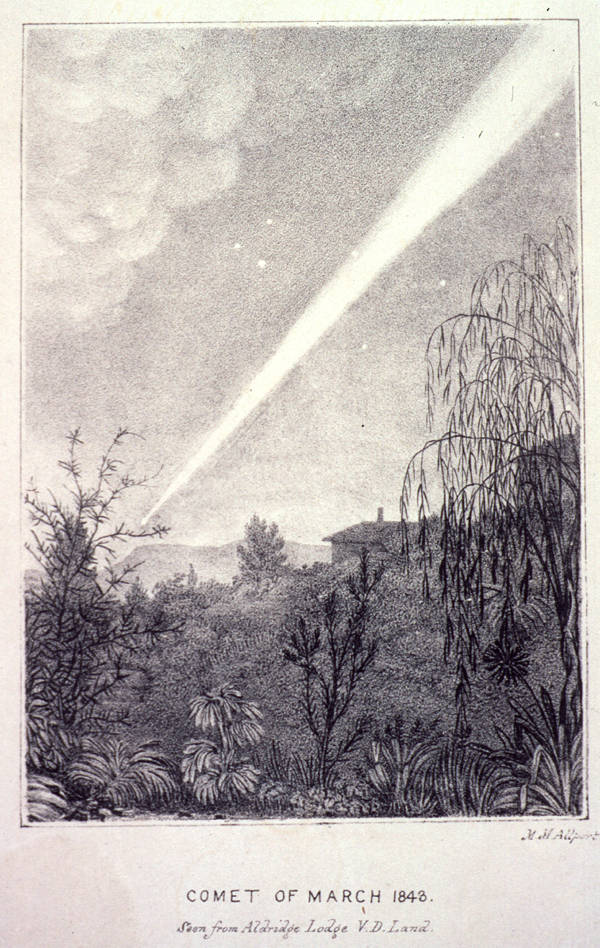

Astronomical events of American Renaissance

Meteor Storm of 1833

Great Comet of 1843

Walt Whitman, Specimen Days. Prose Works 1892, v. 1, ed. Floyd Stovall (New York UP, 1963)

94 "The Weather.--Does it Sympathize with these Times?"

Whether the rains, the heat and cold, and what underlies them all, are affected with what affects man in masses, and follows his play of passionate action, strain'd stronger than usual, and on a larger scale than usual--whether this, or no, it is certain that there is now, and has been for twenty months or more, on this American continent north, many a remarkable, many an unprecedented expression of the subtile air above us and around us. There, since this war, and the wide and deep national agitation, strange analogies, different combinations, a different sunlight, or absence of it; different products even out of the ground. After every great battle, a great storm. Even civic events the same. On Saturday last . . . . As the President came out on the capitol portico, a curious little white cloud, the only one in that part of the sky, appear'd like a hovering bird, right over him.

Indeed, the heavens, the elements, all the meteorological influences, have run riot for weeks past. Such caprices, abruptest alternation of frowns and beauty, I never knew. . . . Nor earth nor sky ever knew spectacles of superber beauty than some of the nights lately here. The western star, Venus, in the earlier hours of the evening, has never been so large, so clear; it seems as if it told something, as if it held rapport indulgent with humanity, with us Americans. Five or six nights since, it hung close by the moon, then a little past its first / 95 quarter. The star was wonderful, the moon like a young mother. The sky, dark blue, the transparent night, the planets, the moderate west wind, the elastic temperature, the miracle of that great star, and the young and swelling moon swimming in the east, suffused the soul. . . . .