LITR 4232 American

Renaissance

Walt Whitman, introduction + “There Was a Child Went Forth” + selections from Song of Myself : sections 1-5, 19, 21, 24, 32-34, 46-52.

| Introducing Whitman presentation: Alicia Atwood--"Child Went Forth," Song of Myself [break] schedule to Thanksgiving Whitman style sheet--"Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" midterm & final |

|

Tuesday, 11 November: Walt Whitman first meeting: introduction 2190-95 + “There Was a Child Went Forth” + selections from Song of Myself : sections 1-5 (pp. 2210-13), 19 (p. 2223), 21 (pp. 2224-5), 24 (pp. 2227-9), 32-34 (pp. 2232-9), 46-52 (pp. 2249-54).

Text-Objective Discussion: Alicia D. Atwood

Thursday, 13 November: Whitman continued: “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” 2263-7

midterm & final

midterms returned Friday

grades

email for grade distribution

remaining schedule

Tuesday, 18 November: Abraham Lincoln 1627-37: "House Divided speech," “Gettysburg Address,” + “Second Inaugural Address.” Research Project due.

Text-Objective Discussion: Cathrine Marie Nunn

Thursday, 20 November: conclude Whitman: “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” 2282-8

Text-Objective Discussion: Lisa Wilson

Tuesday, 25 November: Emily Dickinson first meeting

Introduction 2554-58; Poems: "I like a look of Agony" (2558); "Wild Nights" (2565); "There's a certain slant of light" (2567); "I felt a Funeral, in my Brain" (2568)

Text-Objective Discussion: Bethany Roachell

Tuesday 18 November--3 classes in one: Lincoln, Whitman, Dickinson

presentations:

Cathrine (Lincoln)

Lisa (Whitman)

Bethany (Dickinson)

Overall point of study of Whitman:

Readers today find his style of poetry familiar--wide-open in terms of style and subject matter

But in the mid-1800s Whitman was a revolutionary--no one had written poetry like his before

"free verse" instead of structured, rhymed, parsed lines

poetry not just about pretty, heroic, or uplifting subjects, but poetry about intimacies and complexities of personal and cultural life

introduce Whitman

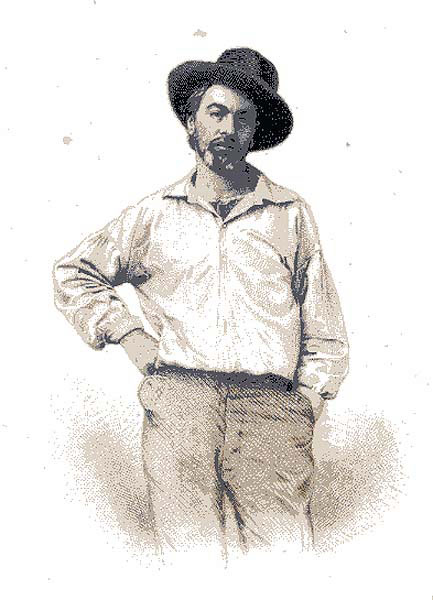

Images

of Whitman from the Walt Whitman Hypertext Archive

"Identification"

3. To use literature as a basis for discussing representative problems and subjects of American culture (New Historicism), such as equality; race, gender, class; modernization and tradition; the family; the individual and the community; nature; the writer's conflicted presence in an anti-intellectual society.

Whitman resolves poetically a problem in American society that can't be resolved otherwise.

All Americans are equal.

Each American is special, unique, an individual.

Inherent contradiction between equality and individuality?

works at inclusiveness, both good and bad are parts of world

identification

identification: absorption, expression of other; other's absorption, identification of self

(correspondence?)

what I assume you shall assume

opposite equals advance

union (sexual, mystical, or both)

union as sex and mysticism

Question: is Whitman talking about sex or God or both?

Metaphor: talking about one thing in terms of another.

"My love is like a red, red rose."

I believe in you my soul, the other I am must not abase

itself to you,

And you must not be abased to the other.

Loaf with me on the grass, loose the stop from your

throat,

Not words, not music or rhyme I want, not custom or lecture, not even the best,

Only the lull I like, the hum of your valved voice.

I mind how once we lay such a transparent summer morning,

How you settled your head athwart my hips and gently turn'd over upon me,

And parted the shirt from my bosom-bone, and plunged your tongue to my bare-stript

heart,

And reach'd till you felt my beard, and reach'd till you held my feet.

Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and knowledge

that pass all the argument of the earth,

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also my brothers, and the women my sisters

and lovers,

And that a kelson of the creation is love

And limitless are leaves stiff or drooping in the fields,

And brown ants in the little wells beneath them,

And mossy scabs of the worm fence, heap'd stones, elder, mullein and poke-weed.

Is this about sex or about a mystical union with God?

The

Varieties of Religious Experience

(1902)

by William James

| Lecture

XVI and XVII: MYSTICISM |

|

.

. . First of all, then, I ask, What does the expression 'mystical states of

consciousness' mean? How do we part off mystical states from other states?

The words 'mysticism' and 'mystical' are often used as terms of mere reproach,

to throw at any opinion which we regard as vague and vast and sentimental, and

without a base in either facts or logic. For some writers a 'mystic' is any

person who believes in thought-transference, or spirit-return. Employed in this

way the word has little value: there are too many less ambiguous synonyms. So,

to keep it useful by restricting it, I will do what I did in the case of the

word 'religion,' and simply propose to you four marks which, when an experience

has them, may justify us in calling it mystical for the purpose of the present

lectures. In this way we shall save verbal disputation, and the recriminations

that generally go therewith.

- 1. Ineffability.- The handiest of the

marks by which I classify a state of mind as mystical is negative. The

subject of it immediately says that it defies expression, that no adequate

report of its contents can be given in words. It follows from this that its

quality must be directly experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred

to others. In this peculiarity mystical states are more like states of

feeling than like states of intellect. No one can make clear to another who

has never had a certain feeling, in what the quality or worth of it

consists. One must have musical ears to know the value of a symphony; one

must have been in love one's self to understand a lover's state of mind.

Lacking the heart or ear, we cannot interpret the musician or the lover

justly, and are even likely to consider him weak-minded or absurd. The

mystic finds that most of us accord to his experiences an equally

incompetent treatment.

- Noetic quality.-

Although so similar to states of feeling, mystical states seem to those who

experience them to be also states of knowledge. They are states of insight

into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect. They are

illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance, all

inarticulate though they remain; and as a rule they carry with them a

curious sense of authority for after-time.

These two characters will entitle any state to be called mystical, in the sense in which I use the word. Two other qualities are less sharply marked, but are usually found. These are: - Transiency.- Mystical states cannot be sustained for long. Except in rare instances, half an hour, or at most an hour or two, seems to be the limit beyond which they fade into the light of common day. Often, when faded, their quality can but imperfectly be reproduced in memory; but when they recur it is recognized; and from one recurrence to another it is susceptible of continuous development in what is felt as inner richness and importance.

- Passivity.- Although the oncoming of mystical states may be facilitated by preliminary voluntary operations, as by fixing the attention, or going through certain bodily performances, or in other ways which manuals of mysticism prescribe; yet when the characteristic sort of consciousness once has set in, the mystic feels as if his own will were in abeyance, and indeed sometimes as if he were grasped and held by a superior power. This latter peculiarity connects mystical states with certain definite phenomena of secondary or alternative personality, such as prophetic speech, automatic writing, or the mediumistic trance. When these latter conditions are well pronounced, however, there may be no recollection whatever of the phenomenon and it may have no significance for the subject's usual inner life, to which, as it were, it makes a mere interruption. Mystical states, strictly so called, are never merely interruptive. Some memory of their content always remains, and a profound sense of their importance. They modify the inner life of the subject between the times of their recurrence. Sharp divisions in this region are, however, difficult to make, and we find all sorts of gradations and mixtures.

The

well-known passage from Walt Whitman is a classical expression of this sporadic

type of mystical experience.

"I believe in you, my Soul...

Loaf with me on the grass, loose the stop from your throat;...

Only the lull I like, the hum of your valved voice.

I mind how once we lay, such a transparent summer morning.

Swiftly arose and spread around me the peace and knowledge that pass all the

argument of the earth,

And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own,

And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,

And that all the men ever born are also my brothers and the women my sisters and

lovers,

And that a kelson of the creation is love."

"The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability

to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the

ability to function."

(F. Scott Fitzgerald, from The Crack-Up)

Bernini, St. Teresa in Ecstasy, the Vatican, Rome

from the Works of St. Teresa, quoted in Marcelle Auclair, Teresa of Avila, trans. Kathleen Pond (Image, 1959), p. 105.

I saw an angel close to me, on my left, in bodily shape a thing granted to me but rarely. He was not large, but small, very beautiful, his face radiant. . . . He held a long golden lance in his hand and I thought its tip was all flames. He seemed to plunge it several times into my heart, right to the very depths of me. When he drew it out, he seemed to pluck my heart out with it, leaving me all on fire with an immense love of God. The pain was so sharp that I moaned but the delight of this tremendous pain is so overwhelming that one cannot wish it to leave one, nor is the soul any longer satisfied with anything less than God. It is a spiritual, not a bodily pain, although the body has some part, even a considerable part, in it. It is an exchange of courtesies between the soul and God . . . so sweet that I beg God to let whoever thinks I'm not telling the truth taste it. . . .