LITR 5831 Colonial &

Postcolonial Literature

Lecture Notes

LITR MA comprehensive exam dates Fall 2015-16

November 6-8

November 20-22

Guantanamera lyrics (based on poem by Jose Marti, Cuban revolutionary poet, 1853-95)

Guantanamero by Sandpipers (1966)

first class meeting on Robinson Crusoe

discussion leader prsn

objective 1 & obj. 2

Crusoe 3.2 talked with them by signs, they were as much afraid of us

Orwell 7

Orwell question #3

3. If colonial literature posits the "self" as European "white man" and the "other" as Eastern, Oriental, Asian, or non-European "natives," how do the two different parties appear to and affect each other? (Put another way, how much does non-verbal social pressure effect a dialogue?)

General Discussion questions

4. If Crusoe is "the first English novel," how does it exemplify the genre or leave your expectations frustrated? How is the novel both romantic and realistic?

5. Dialogue / intertext Crusoe with Orwell's "Elephant": how are both colonial writings, but how does Orwell's text appear more modern, almost postcolonial?

Orwell question #1

1. As formal genre, how does the personal essay resemble or vary from the novel or fiction?

Cannibalism, repression of women, infanticide . . .

At what point does cultural dialogue become threatening?--and imperialism permissible?

1.1 my father a foreigner

1.3 going to sea, x-obey father, something fatal in that propensity of nature

1.5 middle state, middle of two extremes, most suited to human happiness

1.6 temperance, moderation, quietness, health, society

1.7 my elder brother for an example

1.9 I should certainly run away from my master

dialogue: 1.10 [mother paraphrased]; 1.17-1.19 real dialogue

1.28 polysyndeton

1.39 an irresistible reluctance continued to going home

2.2 habit of a gentleman, x-trade

2.5 a sailor and a merchant; for I brought home five pounds nine ounces of gold-dust for my adventure, which yielded me in London, at my return, almost 300 pounds; and this filled me with those aspiring thoughts which have since so completed my ruin.

2.8 from a merchant to a miserable slave

2.17 dialogue

2.19 I turned to the boy, whom they called Xury, and said to him, "Xury, if you will be faithful to me, I'll make you a great man;

2.20 Africa, cannibalism

2.22 the shoot gun

2.25 so much affection as made me love him ever after. Says he, "If wild mans come, they eat me, you go wey."

3.1 Cape Verde, ships from Europe {slave?]

3.2 black and naked

3.2 talked with them by signs, they were as much afraid of us

3.3 two mighty creatures, people esp women frightened, my gun

3.5 women as naked as the men

3.7 a Portuguese ship . . . bound to the coast of Guinea, for negroes.

3.9 a Scotch sailor

3.10 "Seignior Inglese" (Mr. Englishman), "I will carry you thither in charity

3.12 He offered me also sixty pieces of eight more for my boy Xury . . . he would give the boy an obligation to set him free in ten years, if he turned Christian

3.14 in a word, I made about two hundred and twenty pieces of eight of all my cargo; and with this stock I went on shore in the Brazils.

3.15 letter of naturalization, I purchased as much land that was uncured as my money would reach, and formed a plan for my plantation and settlement

3.16 made each of us a large piece of ground ready for planting canes [i.e. sugar] in the year to come. But we both wanted help; and now I found, more than before, I had done wrong in parting with my boy Xury.

3.17 I was coming into the very middle station, or upper degree of low life, which my father advised me to before, and which, if I resolved to go on with, I might as well have stayed at home

3.18 I lived just like a man cast away upon some desolate island, that had nobody there but himself.

3.21 she not only delivered the money, but out of her own pocket sent the Portugal captain a very handsome present for his humanity and charity to me.

3.23 the captain, had laid out the five pounds, which my friend had sent him for a present for himself, to purchase and bring me over a servant, under bond for six years' service,

3.24 means to sell them to a very great advantage

3.24 the first thing I did, I bought me a negro slave, and an European servant also—I mean another besides that which the captain brought me from Lisbon.

3.25 I raised fifty great rolls of tobacco

3.25 my head began to be full of projects and undertakings beyond my reach; such as are, indeed, often the ruin of the best heads in business

3.27 not only gold-dust, Guinea grains, elephants' teeth, &c., but negroes, for the service of the Brazils, in great numbers.

3.33 obeyed blindly the dictates of my fancy rather than my reason

3.33 an evil hour, the 1st September 1659, being the same day eight years that I went from my father and mother at Hull

3.34 such toys as were fit for our trade with the negroes, such as beads, bits of glass, shells, and other trifles, especially little looking-glasses, knives, scissors, hatchets, and the like.

3.38 we were rather in danger of being devoured by savages than ever returning to our own country.

3.50 that there should not be one soul saved but myself; for, as for them, I never saw them afterwards, or any sign of them, except three of their hats, one cap, and two shoes that were not fellows. [realistic detail]

4.3 a fresh renewing of my grief; for I saw evidently that if we had kept on board we had been all safe

4.3 all the ship's provisions were dry and untouched by the water

4.4 a great deal of labor and pains > raft

4.5 tools more valuable than gold

4.9 efficient realistic description of natural process effecting rescue of raft

4.10 realistic description, too much detail? but consistent observation

4.12 the first gun that had been fired there since the creation of the world

4.13 some wild beast might devour me, though, as I afterwards found, there was really no need for those fears.

4.18 a creature like a wild cat

4.24 now thirteen days on shore

4.24 about thirty-six pounds value in money—some European coin, some Brazil, some pieces of eight, some gold, and some silver.

[4.25] I smiled to myself at the sight of this money: "O drug!" (cf. utopias)

4.25 upon second thoughts I took it away

4.26 when I looked out, behold, no more ship was to be seen!

4.40 thus I made me a cave, just behind my tent, which served me like a cellar to my house.

4.43 goats in the island

4.43 from whence I concluded that, by the position of their optics, their sight was so directed downward that they did not readily see objects that were above them; so afterwards I took this method—I always climbed the rocks first, to get above them, and then had frequently a fair mark.

[4.45] Having now fixed my habitation, I found it absolutely necessary to provide a place to make a fire in, and fuel to burn: and what I did for that, and also how I enlarged my cave, and what conveniences I made, I shall give a full account of in its place; but I must now give some little account of myself, and of my thoughts about living, which, it may well be supposed, were not a few.

4.46 a determination of Heaven

4.46 so without help, abandoned, so entirely depressed, that it could hardly be rational to be thankful for such a life.

4.47 something always returned swift upon me to check these thoughts

4.47 reason, as it were, expostulated with me the other way

4.50 And now being about to enter into a melancholy relation of a scene of silent life, such, perhaps, as was never heard of in the world before, I shall take it from its beginning, and continue it in its order. It was by my account the 30th of September, when

4.51 lose my reckoning of time for want of books, and pen and ink, and should even forget the Sabbath days

4.51 a great cross, I set it up on the shore where I first landed—"I came on shore here on the 30th September 1659."

4.53 pens, ink, and paper, several parcels in the captain's, mate's, gunner's and carpenter's keeping; three or four compasses, some mathematical instruments, dials, perspectives, charts, and books of navigation,

4.53 two or three Popish prayer-books

4.69 scarce any condition in the world so miserable but there was something negative or something positive to be thankful for in it [aphorism]

4.69 to set, in the description of good and evil, on the credit side of the account.

4.73 to make such necessary things as I found I most wanted, particularly a chair and a table

4.73 as reason is the substance and origin of the mathematics, so by stating and squaring everything by reason, and by making the most rational judgment of things, every man may be, in time, master of every mechanic art.

4.75 began to keep a journal of every day's employment

![]()

discuss Crusoe

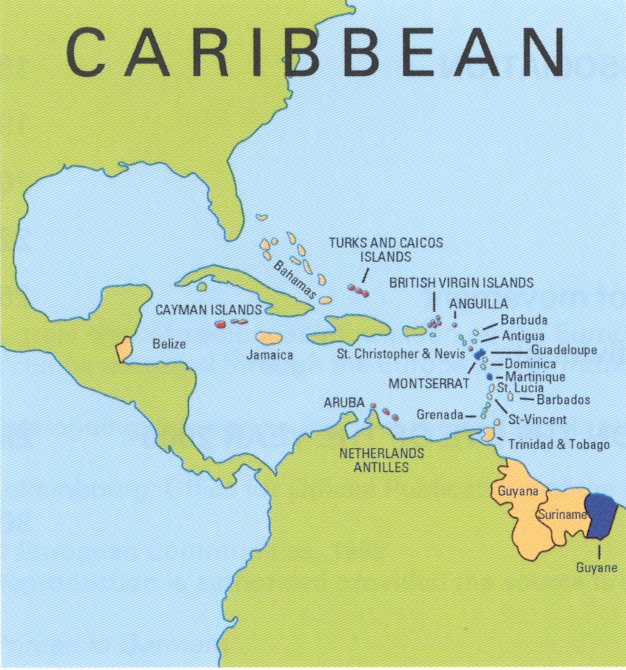

The CARIBBEAN / The "New World"

Daniel Defoe’s Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719)

in dialogue with

Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy (1990)

Robinson Crusoe the “first” English novel: heavy on narrative, short on dialogue

If you haven’t read Robinson Crusoe before, ask yourself . . .

What do you know about the story? What images does our culture share from the text, regardless of whether we’ve read it or not?

What changes when you actually read it?

One of biggest challenges: What about presence of slavery? How does that affect the popular image of Robinson Crusoe?

Added questions:

How do you identify Robinson Crusoe as a novel?

What makes you not want to call it a novel?

Ian Watt, "Robinson Crusoe, Individualism, and the Novel" (handout)

classic "historicist" reading of novel

start article, through p. 69

1. To bring classic literature of European colonialism and emerging literature from the postcolonial world into dialogue.

Robinson Crusoe as fundamental or "classic" expression of modern western ideology--what we think without knowing we think it

reinforces Bakhtin on novel as genre of modernity: open-ended future, multivocal expression

Watt associates emergence of the novel with emergence of individualism and capitalism

Since article was written in 1957, literary studies would add "colonialism"

![]()

|

|

Daniel Defoe Adventures of Robinson Crusoe |

|

Robinson Crusoe Island (Juan Fernandez)

Alexander Selkirk, the real Robinson Crusoe

online copy of Robinson Crusoe

biography of Defoe with links to pages on Crusoe & Further Adventures

Defoe's sentences

not a modern sentence--very little subordination

long sentences, but not like Faulkner's long sentences

typical of 16th-17th century prose: plain speech, but adds and adds, piles up predicates.

Walcott poem: "Crusoe's Island"

Preview questions:

1. The poem makes numerous references to elements of the Genesis Creation story--e. g., "Adam," "Eden," + other biblical allusions. What are the implications of the myths or stories involved?

2. What contrasts and continuities are possible between the poem's speaker as a lonely Crusoe type and the "black little girls" at the end?

3. What are the implications for Friday's racial identity?

Crusoe can't return home, but rebuilds home in strange land.

Aaron Schneider's written answers to discussion questions, fall 2009

1. If Crusoe is the “1st English Novel” how does it exemplify the genre or leave your expectations frustrated?

In identifying Robinson Crusoe as the “1st English Novel” we can assume it to have characteristics of the Romantic time period from which the English Novel evolved. In matching the novel to 18th century literature, we find that Defoe attains the characteristics of nature, love of the common man, heroism, and the love of strange and faraway places. In our protagonist we find the plight of a common man rising to heroism. While Crusoe could be considered a shallow, emotionless character, he could also be considered a hero because of his victory over his circumstances. Not only does he survive a tragic storm at sea, he manages to build a life out of nothing (pulling himself up by his own bootstraps) on a deserted island. His closeness with nature (while in conflict with it) and using what Mother Nature provides allows for his survival. The fact that Defoe chooses to have our protagonist endure these hardships in isolation only helps to re-enforce the Christian allegory that man is dependent on a greater being. In incorporating all of these elements, Defoe does indeed satisfy the expectations of being the “1st English Novel”

2. What attitudes does Crusoe show toward home, family, and career? How are these modern or traditional?

As we are introduced to Robinson Crusoe, we are also introduced to a very modern protagonist. Perhaps it is because he could be deemed as a “modern” character that Defoe chooses to punish him many times over for the very modern decisions he makes. We see the tradition of the time period through Crusoe’s parents who are both very passionate about family and the middle class lifestyle. They believe in the ideals of contentment with being “upper-lower class” and in one pursuing a profession within the community. It is the hope of Crusoe’s father that he will enter a respectable trade as an apprentice in order to stay close to family and kinsmen. Crusoe’s desire is not to endanger his relationship with his family (though he shows no deep attachment to them other than worrying about religious implications placed on him for disobeying them), but to express his individualism, which is a very modern way of thinking. In a traditional community authority figures set the rules determining what is right and wrong and those in the community typically obey for the fear and embarrassment of retribution. In a modern society, such as we live today, young men and women simply see these rules as the line to cross; they are made for nothing more than breaking. Crusoe’s career choice does not stem necessarily from a “passion for the sea” or a desire to pursue a particular profession because it is his “dream”, but rather to show that he is capable of making decisions for himself. In making these decisions, we are many times led back to Crusoe feeling he has been “cursed” or “condemned” for disobeying his father’s advice. It would seem that Defoe is suggesting, in accordance with the times, that the traditional lifestyle is correct and youths must face the trials of inexperience that comes with rebellious decisions.

3. How does Crusoe’s individual life correspond to England’s history as an imperial-colonial nation?

Robinson Crusoe’s life (up through The Journal) appears to directly correspond with England’s identity as an imperial-colonial nation. Numerous times throughout the text Crusoe has the opportunity to stay at home and create a modest life for himself; instead, he chooses to travel abroad and seek out destinations and adventures in other nations. Instead of being content with what he already has, he is driven by blind ambition which even he cannot explain (as stated in the text), “But I was hurried on, and obeyed blindly the dictates of my fancy rather than my reason”. (60) In much the same way, England was driven to consume 25% of the world’s landmass to possess other people and their properties. Crusoe’s sole purpose in taking his “fatal trip” is to deal in slave ownership and trading for his plantation in Brasils. While it is safe to state that without “adventurers” and “pioneers” the country we now live in might not have been founded, it is this pursuit of adventure and lack of contentment that aligns our novel’s protagonist Robinson Crusoe with his English homeland.