|

LITR 5431 Seminar in American Literature:

Romanticism lecture notes |

|

|

2 big questions for tonight re Romanticism--not that we'll finish but such questions can motivate, organize, extend and redeem teaching and learning

Is Romanticism simply an antiquarian subject--an object of charm and nostalgia from an earlier time that we indulge or condescend to--or are the dynamics and questions represented by Romanticism still living two centuries later, though in evolved or adapted forms?

Since Romanticism originated in Europe and extended to European-America, is its study limited to studies of Western Civilization? Or are its themes and dynamics universal? Either way, can studies of Romanticism fairly incorporate studies of multicultural traditions (in this case African America) that do not originate in Western Europe but are nonetheless involved through language and cultural exchange? (+ what further questions are raised?)

Course like Romanticism itself--doesn't define itself too closely, therefore adaptable to wide range of purposes

Discussion questions: What Romantic survivals or variations in today's readings? How much has Romanticism become a universal, and how much are its survivals quaint, limited, rote period references?

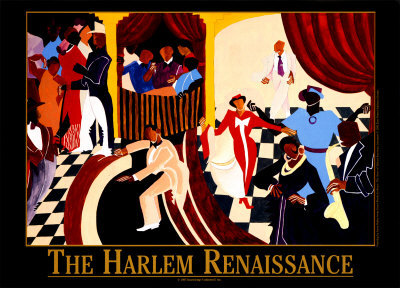

Literary periodization: The Harlem Renaissance and Fitzgerald's career are Modernist in chronology. For the Harlem Renaissance of African American culture, though, the term operates at one remove, as this movement is also associated with a more-or-less distinct cultural tradition and its diverse arts including jazz. As with classifying the Slave Narratives within Romanticism, is it fair to classify the Harlem Renaissance as Modernism?

White patrons of the Harlem Renaissance encouraged "primitivism" in their styles. Where and how does this aspect of Modernism appear?

achievement: Romanticism still means a lot of different things, but . . .

term provides shorthand for period, genres, values

any term can become oppressive or limiting, but may also provide yardstick for measuring difference or variation

last week: gothic > grotesque

practice language, practice critical thinking--the conversation continues even as differences are acknowledged

Fitzgerald, "Winter Dreams": 1. If Fitzgerald is a Modernist with a Realistic surface, how do he and this text continue to represent a romance narrative or a Romantic perspective? How much is Fitzgerald's persona, mystique, or perspective merely American? How has Romanticism changed in the century since its peak?

2. How does Judy Jones resemble Daisy Miller as "the American Girl" and subject / object of romance? Or Cora in Mohicans, Poe's Ligeia, Jacobs's slave girl, Sylvia in "White Heron," or Miranda in "The Grave?"

2.14 impossible to determine whether this question was ingenuous or malicious. [cf. Daisy]

2.16 arrestingly beautiful

2.18 All she needs is to be turned up and spanked for six months and then to be married off to an old-fashioned cavalry captain."

2.20 "she always looks as if she wanted to be kissed!

[2.37] "Go faster," she called, "fast as it'll go."

2.42 for the second time, her casual whim gave a new direction to his life.

4.5 she did it all herself. She was not a girl who could be "won" in the kinetic sense

4.36 She would have been soiled long since had there been anything to soil her—except herself—but this was her own self outpouring.

[4.49] "Of course you could never love anybody but me," she continued. "I like the way you love me. Oh, Dexter, have you forgotten last year?"

[4.52] Was she sincerely moved—or was she carried along by the wave of her own acting?

[4.53] "I wish we could be like that again," she said, and he forced himself to answer:

[4.61] "I'm more beautiful than anybody else," she said brokenly, "why can't I be happy?"

3. If Americans can't talk about class, how does Fitzgerald bring us near? Compare "class" as identity-determinant with race and gender?

4.8 No disillusion as to the world in which she had grown up could cure his illusion as to her desirability.

[1.11] The little girl who had done this . . . the almost passionate quality of her eyes. Vitality is born early in such women. It was utterly in evidence now, shining through her thin frame in a sort of glow.

2.26 Later in the afternoon the sun went down with a riotous swirl of gold and varying blues and scarlets, and left the dry, rustling night of Western summer. Dexter watched from the veranda of the Golf Club, watched the even overlap of the waters in the little wind, silver molasses under the harvest-moon. Then the moon held a finger to her lips and the lake became a clear pool, pale and quiet. Dexter put on his bathing-suit and swam out to the farthest raft, where he stretched dripping on the wet canvas of the springboard.

2.28 a sort of ecstasy and it was with that ecstasy he viewed what happened to him now. It was a mood of intense appreciation, a sense that, for once, he was magnificently attuned to life and that everything about him was radiating a brightness and a glamour he might never know again.

2.35 a fish jumping and a star shining and the lights around the lake were gleaming.

Watching her was without effort to the eye, watching a branch waving or a sea-gull flying. [cf. Ligeia 6]

3.19 creating want

3.20 a proud, desirous little boy

[6.34] The dream was gone. Something had been taken from him. In a sort of panic he pushed the palms of his hands into his eyes and tried to bring up a picture of the waters lapping on Sherry Island and the moonlit veranda, and gingham on the golf-links and the dry sun and the gold color of her neck's soft down. And her mouth damp to his kisses and her eyes plaintive with melancholy and her freshness like new fine linen in the morning. Why, these things were no longer in the world! They had existed and they existed no longer.

[6.35] For the first time in years the tears were streaming down his face. But they were for himself now. He did not care about mouth and eyes and moving hands. He wanted to care, and he could not care. For he had gone away and he could never go back any more. The gates were closed, the sun was gone down, and there was no beauty but the gray beauty of steel that withstands all time. Even the grief he could have borne was left behind in the country of illusion, of youth, of the richness of life, where his winter dreams had flourished.

[6.36] "Long ago," he said, "long ago, there was something in me, but now that thing is gone. Now that thing is gone, that thing is gone. I cannot cry. I cannot care. That thing will come back no more."

[cf. conclusion to Wolfe's The Lost Boy]

[2.3] It was a small laundry when he went into it but Dexter made a specialty of learning how the English washed fine woollen golf-stockings without shrinking them, and within a year he was catering to the trade that wore knickerbockers.

[3.16] "I'm nobody," he announced. "My career is largely a matter of futures."

"I'm probably making more money than any man my age in the Northwest. I know that's an obnoxious remark, but you advised me to start right."

[3.19] There was a pause. Then she smiled and the corners of her mouth drooped and an almost imperceptible sway brought her closer to him

1.46 Dexter was unconsciously dictated to by his winter dreams.

3.1 he was better than these men. He was newer and stronger. Yet in acknowledging to himself that he wished his children to be like them he was admitting that he was but the rough, strong stuff from which they eternally sprang.

[4.28] The familiar voice at his elbow startled him. Judy Jones had left a man and crossed the room to him—Judy Jones, a slender enamelled doll in cloth of gold: gold in a band at her head, gold in two slipper points at her dress's hem. The fragile glow of her face seemed to blossom as she smiled at him. A breeze of warmth and light blew through the room. His hands in the pockets of his dinner-jacket tightened spasmodically. He was filled with a sudden excitement.

[Modernism: surprising and sometimes inconsistent metaphors for interior states; cf. Porter, "The Grave" para. 11: "Miranda, with her powerful social sense, which was like a fine set of antennae radiating from every pore of her skin, would feel ashamed "

Winter Dreams

1.4 car as class, class-struggle

[1.11] The little girl who had done this . . . the almost passionate quality of her eyes. Vitality is born early in such women. It was utterly in evidence now, shining through her thin frame in a sort of glow.

[1.15] "Well, I guess there aren't very many people out here this morning, are there?"

1.19 he had not realized how young she was

[1.34] Miss Jones and her retinue . . . became involved in a heated conversation, which was concluded by Miss Jones taking one of the clubs and hitting it on the ground with violence. For further emphasis she raised it again and was about to bring it down smartly upon the nurse's bosom

1.46 Dexter was unconsciously dictated to by his winter dreams.

[2.1] He wanted not association with glittering things and glittering people—he wanted the glittering things themselves. . . .. It is with one of those denials and not with his career as a whole that this story deals.

[2.3] It was a small laundry when he went into it but Dexter made a specialty of learning how the English washed fine woollen golf-stockings without shrinking them, and within a year he was catering to the trade that wore knickerbockers.

2.4 a guest card to the Sherry Island Golf Club

lessen the gap which lay between his present and his past.

2.14 impossible to determine whether this question was ingenuous or malicious. [cf. Daisy]

2.16 arrestingly beautiful

2.18 All she needs is to be turned up and spanked for six months and then to be married off to an old-fashioned cavalry captain."

2.20 "she always looks as if she wanted to be kissed!

[2.25] "Better thank the Lord she doesn't drive a swifter ball," said Mr. Hart, winking at Dexter. [class-inclusion]

2.26 Later in the afternoon the sun went down with a riotous swirl of gold and varying blues and scarlets, and left the dry, rustling night of Western summer. Dexter watched from the veranda of the Golf Club, watched the even overlap of the waters in the little wind, silver molasses under the harvest-moon. Then the moon held a finger to her lips and the lake became a clear pool, pale and quiet. Dexter put on his bathing-suit and swam out to the farthest raft, where he stretched dripping on the wet canvas of the springboard.

2.28 a sort of ecstasy and it was with that ecstasy he viewed what happened to him now. It was a mood of intense appreciation, a sense that, for once, he was magnificently attuned to life and that everything about him was radiating a brightness and a glamour he might never know again.

2.34 I live in a house over there on the Island, and in that house there is a man waiting for me. When he drove up at the door I drove out of the dock because he says I'm his ideal."

2.35 a fish jumping and a star shining and the lights around the lake were gleaming.

Watching her was without effort to the eye, watching a branch waving or a sea-gull flying. [cf. Ligeia 6]

[2.37] "Go faster," she called, "fast as it'll go."

2.42 for the second time, her casual whim gave a new direction to his life.

3.1 he was better than these men. He was newer and stronger. Yet in acknowledging to himself that he wished his children to be like them he was admitting that he was but the rough, strong stuff from which they eternally sprang.

[3.9] "Do you mind if I weep a little?" she said.

3.11 There was a man I cared about, and this afternoon he told me out of a clear sky that he was poor as a church-mouse.

[3.14] "Let's start right," she interrupted herself suddenly. "Who are you, anyhow?"

[3.15] For a moment Dexter hesitated. Then:

[3.16] "I'm nobody," he announced. "My career is largely a matter of futures."

"I'm probably making more money than any man my age in the Northwest. I know that's an obnoxious remark, but you advised me to start right."

[3.19] There was a pause. Then she smiled and the corners of her mouth drooped and an almost imperceptible sway brought her closer to him

3.19 creating want

3.20 a proud, desirous little boy

4.1 Dexter surrendered a part of himself to the most direct and unprincipled personality with which he had ever come in contact. Whatever Judy wanted, she went after with the full pressure of her charm.

4.2 a beautiful and romantic thing to say

4.3 one of a varying dozen who circulated about her.

4.3 Judy made these forays upon the helpless and defeated without malice, indeed half unconscious that there was anything mischievous in what she did.

4.5 she did it all herself. She was not a girl who could be "won" in the kinetic sense

4.6 The helpless ecstasy of losing himself in her was opiate rather than tonic.

4.8 No disillusion as to the world in which she had grown up could cure his illusion as to her desirability.

4.11 ecstatic happiness and intolerable agony of spirit

4.12 occurred to him that he could not have Judy Jones.

4.13 It hurt him that she did not miss these things—that was all.

4.14 the young and already fabulously successful Dexter Green

4.16 He ceased to be an authority on her.

4.17 Irene would be no more than a curtain spread behind him, a hand moving among gleaming tea-cups, a voice calling to children . . . fire and loveliness were gone, the magic of nights and the wonder of the varying hours and seasons . . . slender lips, down-turning, dropping to his lips and bearing him up into a heaven of eyes. . . . The thing was deep in him. He was too strong and alive for it to die lightly.

4.27] "Hello, darling."

[4.28] The familiar voice at his elbow startled him. Judy Jones had left a man and crossed the room to him—Judy Jones, a slender enamelled doll in cloth of gold: gold in a band at her head, gold in two slipper points at her dress's hem. The fragile glow of her face seemed to blossom as she smiled at him. A breeze of warmth and light blew through the room. His hands in the pockets of his dinner-jacket tightened spasmodically. He was filled with a sudden excitement.

[Modernism: surprising and sometimes inconsistent metaphors for interior states; cf. Porter, "The Grave" para. 11: "Miranda, with her powerful social sense, which was like a fine set of antennae radiating from every pore of her skin, would feel ashamed "

[4.31] She turned and he followed her. She had been away—he could have wept at the wonder of her return. She had passed through enchanted streets, doing things that were like provocative music. All mysterious happenings, all fresh and quickening hopes, had gone away with her, come back with her now.

4.36 She would have been soiled long since had there been anything to soil her—except herself—but this was her own self outpouring.

[4.39] "Have you missed me?" she asked suddenly.

[4.45] "I'm awfully tired of everything, darling." She called every one darling, endowing the endearment with careless, individual comraderie. "I wish you'd marry me."

[4.46] The directness of this confused him. He should have told her now that he was going to marry another girl, but he could not tell her. He could as easily have sworn that he had never loved her.

[4.49] "Of course you could never love anybody but me," she continued. "I like the way you love me. Oh, Dexter, have you forgotten last year?"

[4.52] Was she sincerely moved—or was she carried along by the wave of her own acting?

[4.53] "I wish we could be like that again," she said, and he forced himself to answer:

4.57 "I don't want to go back to that idiotic dance—with those children."

[4.58] Then, as he turned up the street that led to the residence district, Judy began to cry quietly to herself. He had never seen her cry before.

[4.61] "I'm more beautiful than anybody else," she said brokenly, "why can't I be happy?"

[6.5] "Judy Simms," said Devlin with no particular interest; "Judy Jones she was once."

[6.9] "Oh, Lud Simms has gone to pieces in a way. I don't mean he ill-uses her, but he drinks and runs around "

[6.11] "No. Stays at home with her kids."

[6.13] "She's a little too old for him," said Devlin.

[6.23] "Well, that's, I told you all there is to it. He treats her like the devil. Oh, they're not going to get divorced or anything. When he's particularly outrageous she forgives him. In fact, I'm inclined to think she loves him. She was a pretty girl when she first came to Detroit."

[6.29] "I'm not trying to start a row," he said. "I think Judy's a nice girl and I like her. I can't understand how a man like Lud Simms could fall madly in love with her, but he did." Then he added: "Most of the women like her."

[6.34] The dream was gone. Something had been taken from him. In a sort of panic he pushed the palms of his hands into his eyes and tried to bring up a picture of the waters lapping on Sherry Island and the moonlit veranda, and gingham on the golf-links and the dry sun and the gold color of her neck's soft down. And her mouth damp to his kisses and her eyes plaintive with melancholy and her freshness like new fine linen in the morning. Why, these things were no longer in the world! They had existed and they existed no longer.

[6.35] For the first time in years the tears were streaming down his face. But they were for himself now. He did not care about mouth and eyes and moving hands. He wanted to care, and he could not care. For he had gone away and he could never go back any more. The gates were closed, the sun was gone down, and there was no beauty but the gray beauty of steel that withstands all time. Even the grief he could have borne was left behind in the country of illusion, of youth, of the richness of life, where his winter dreams had flourished.

[6.36] "Long ago," he said, "long ago, there was something in me, but now that thing is gone. Now that thing is gone, that thing is gone. I cannot cry. I cannot care. That thing will come back no more."

[cf. conclusion to Wolfe's The Lost Boy]

![]()

Harlem Renaissance writers: 4. What is Modernist yet resiliently Romantic about these writers and their texts? How do they inherit, capitalize on, and transform Romantic styles or subjects?

5. As with the slave narratives, how does including African American literature stress and test the limits of Romanticism? Should minority traditions be mainstreamed or separate but equal?

Recall discussion of slave narratives: mainstream Romanticism or separate tradition of African American literature?

rationale for mainstreaming: may help create common ground for different cultural traditions

rationale against mainstreaming: common ground is still on dominant culture's terms; separate tradition threatened by assimilation

possible resolution: acknowledge shared forms but also differences

Harlem Renaissance might be studied not as phenomenon of Romanticism but within several other traditions or lines of study:

African American or Minority Literature

Modernism (1st half of 20th century)

Interdisciplinary or multi-media movement: not just literature but music (jazz), theater, and visual art, not to mention study of cultural movement involving migration of many rural or southern blacks to northern urban centers.

(As a result of this last aspect, much Harlem Renaissance material is finding a home on the web--literature + visuals + sound.)

Zora Neal Hurston, "How it Feels to be Colored Me"

Discussion for Hurston, "How it Feels to be Colored Me":

Is African American literature / culture / identity part of larger American identity or separate?

Hurston as figure of Harlem Renaissance; experience crossing from black to white cultures > in-between attitude

Hurston's life 1891-1960

Harlem Renaissance 1910s-20s > Great Depression 1929 & New Deal 1930s-40s

Hurston studies at Columbia University w/ leading anthropologists, does anthropological field-work in Florida

Hurston sometimes in conflict with male leaders of Harlem Renaissance

Hurston popular performer in Jazz-Age settings for white patrons (much black-white cultural interaction in Jazz Age in USA & Europe)

Hurston opposed New Deal government action to employ poor and securitize middle-class

> found herself on opposite sides politically from most African Americans

> worked for various right-wing organizations opposing New Deal

Continued writing and publishing in 1930s and 40s

Near end of life, worked as domestic

Grave marker provided by Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple

How may "How it Feels to be Colored Me" embody both the Dream and the American Dream? In what ways does it depict both an African American experience and a more universal or all-American experience?

Is the text an essay or a story?

2 affirmation of black or individual identity; cf. Jacobs not knowing she was a slave; also Douglass in Bondage & Freedom

3 family oppose?

Chamber of Commerce

4 [performance] deplored joyful, but their Zora

5 Zora > little colored girl

6 not tragically colored, x-sobbing school of negrohood [Emersonian self-reliance, disocciation]

7 slaves x-depression

7 Slavery is the price I paid for civilization, and the choice was not

with me. It is a bully adventure and worth all that I have paid through

my ancestors for it. No one on earth ever had a greater chance for

glory. The world to be won and nothing to be lost. It is thrilling to

think, to know that for any act of mine, I shall get twice as much

praise or twice as much blame. It is quite exciting to hold the center

of the national stage, with the spectators not knowing whether to laugh

or to weep.

8 The game of keeping what one has is never so exciting as the game of

getting.

14 across the ocean and the continent that have fallen between us. He is so pale with his whiteness then and I am so colored.

15 Seventh Avenue, Harlem City

[16]

I have no separate feeling about being an American citizen and colored. I am

merely a fragment of the Great Soul that surges within the boundaries. My

country, right or wrong.

[17]

Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It

merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company?

It's beyond me.

18 a brown bag of miscellany . . . in company with other bags, white, red and yellow.

18 Who knows?

Claude McKay, "Harlem Dancer," "Harlem Shadows," "If We Must Die"

models: sonnet forms, European genres, aesthetics

"Harlem Shadows": Realism: lower-class characters, prostitutes, dancers

"desire's call" degraded

"heart of me . . . street to street"

race-conscious as separate from universal?

"Harlem Dancer" [real self inside]

individual separate from masses

perfection of form

"If We Must Die"

idealized situation

archaic language

primitivism

honor: let us nobly die

Langston Hughes, "Harlem" & "Dream Variations,"

models: jazz and other African American musical forms

jazz as primitive

"How it Feels to be Colored Me" 12

rhymes

natural metaphors for soul

Realism: vernacular speech "done shut"

Lenox Avenue, local color, regional detail

tears as loss

rhyme scheme improvised