|

Craig White's Literature Courses

authors |

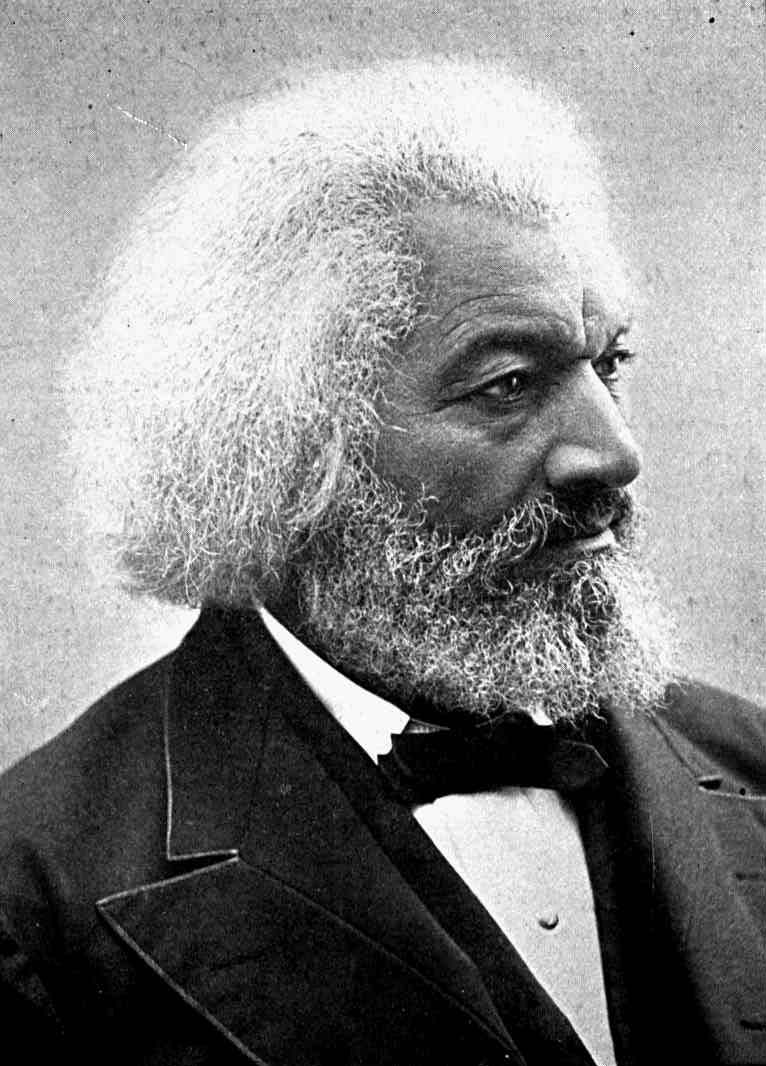

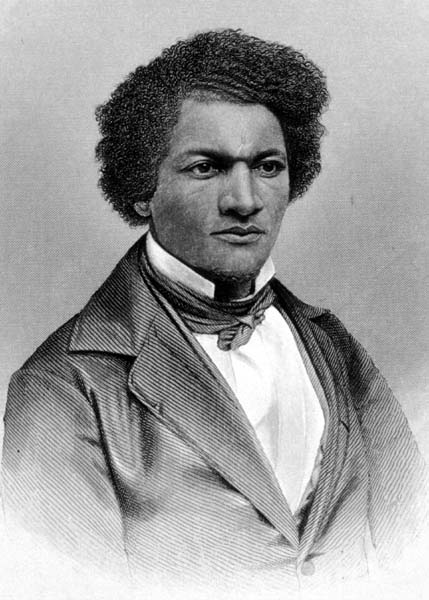

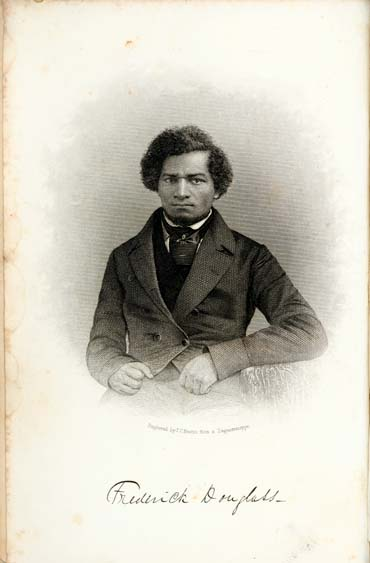

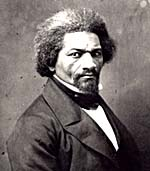

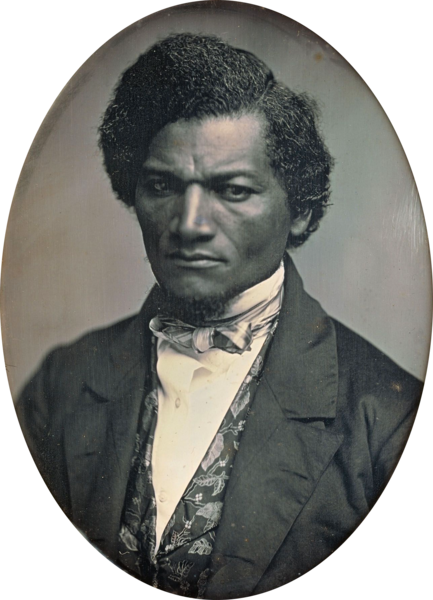

photo from frontispiece to Life & Times of Frederick Douglass |

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) |

|

Frederick Douglass was the leading African American author and activist of the 19th-century United States—"the Lincoln of African America," as he's sometimes characterized.

Born into slavery in 1818, Douglass was first raised by his maternal grandparents in their cabin on Maryland's Eastern Shore. As a boy and teenager he spent years in Baltimore, where he learned to read and write, largely on his own. Back on the Eastern Shore as a teenager, he worked several years as a field hand, subsequently returning to Baltimore and learning a trade as a ship's caulker while turning over most of his earnings to his master.

In 1838 (at around 20 years of age) Douglass's freeborn fiancee Anna Murray helped him escape to the North, where he became a shipyard laborer and subsequently a leading public speaker for the Abolition of slavery, then an author, journalist, and activist. Throughout his life Douglass campaigned for equal rights for all people, including women.

As a writer Douglass is best known for his mastery and development of the slave narrative. This popular autobiographical genre of a person's experience with slavery, escape to freedom, and commitment to Abolition or racial uplift became a foundational text or origin story for African American literature.

In 1845 Douglass published the first edition of his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.

Of hundreds of slave narratives published from the 1700s to the early 20th century, Douglass's is widely regarded as the genre's masterpiece. Douglass's Narrative is now widely read in American high schools and colleges as a foundational text of African American literature and an essential text of the American Renaissance.

Altogether Douglass wrote three versions of his life story—the second two expanding the contents of their predecessors:

-

1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (app. 100 pages in Library of America compendium edition)

-

1855 My Bondage and My Freedom (app. 350 pages)

-

1881, 1892 The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (app. 600 pages)

Each later volume includes the text of the previous volume(s) with new materials added or interpolated; the autobiographies are not sequential (like Maya Angelou's 5 memoirs beginning with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings) but incremental.

![]()

Other highlights of Douglass's career:

1847 begins editing and writing his own newspaper (orig. title The North Star, later Frederick Douglass' Paper with variations).

His newspaper's motto: "Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren."

1848 attends Seneca Falls Convention, the USA's first women's rights convention that produced the Declaration of Sentiments based on the Declaration of Independence. Douglass spoke in favor of women's suffrage, supporting the convention's organizer Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

late 1850s meets repeatedly with John Brown, radical abolitionist and leader of 1859 insurrection-raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Douglass supported some of Brown's earlier schemes to free slaves and weaken the Southern slave system but argued against the Harpers Ferry raid.

1863 Douglass confers with President Abraham Lincoln concerning conditions and treatment of African American soldiers in Union army, an interview depicted in The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.

1877 appointed U.S. Marshal to District of Columbia (escorted foreign dignitaries to meet President of USA; led inaugural procession).

1881 apointed Recorder of Deeds for District of Columbia.

1889-91 appointed U.S. Consul-General to the Republic of Haiti. ("Consul-general" comparable to "Ambassador.")

1892 supervises construction of rental housing for blacks in Fells Point neighborhood of Baltimore on former site of Dallas Street Station Methodist Episcopal Church, which he attended in 1820s-30s; buildings are now known as "Douglass Place" in National Register of Historic Places.

After Douglass's death, his birthday (14 February, by his designation) became the seed of Black History Month.

![]()

New York Times review of David Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (2018)

Interview with David Blight, author, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (2018)

![]()

Douglass's Personal Life

Anna Murray Douglass (1813-82) |

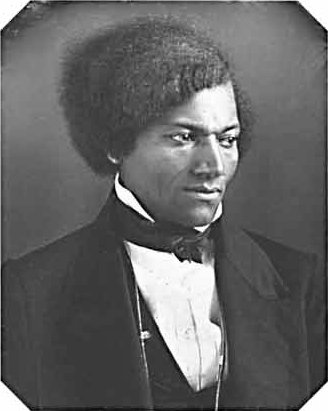

Frederick Douglass, photo from 1848 |

Born in 1818 as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. His mother Harriet Bailey was a slave who, Douglass reports in My Bondage and My Freedom, could read and write. In Narrative Douglass writes that "[t]he opinion was . . . whispered that my master was my father," but Douglass never identifies which of his owners is referred to, and Bondage and Freedom expresses doubts on this rumor.

In 1838—at age 20—Douglass escaped to the North and, eleven days later in New York City, married Anna Murray (1813-82), a freeborn African American woman working as a laundress in Denton, Maryland. Taking her laundry work to the town's docks, she met Frederick who was employed on the docks as a ship's caulker.

Anna Murray helped Douglass escape by providing him with sailor's clothing from her laundry work and giving him part of her savings, augmented by selling a feather bed.

Within ten years of their marriage the Douglasses had five children: Rosetta, Lewis, Frederick Jr., Charles and Annie.

Anna was active in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. When the Douglasses lived in Rochester, NY, their home served as a station on the Underground Railroad to nearby Canada.

In 1877 the family moved to a home above the Anacostia River in Washington, DC, naming it Cedar Hill, which is now the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

"Cedar Hill," Douglass's home near the Anacostia River in Washington DC,

now the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

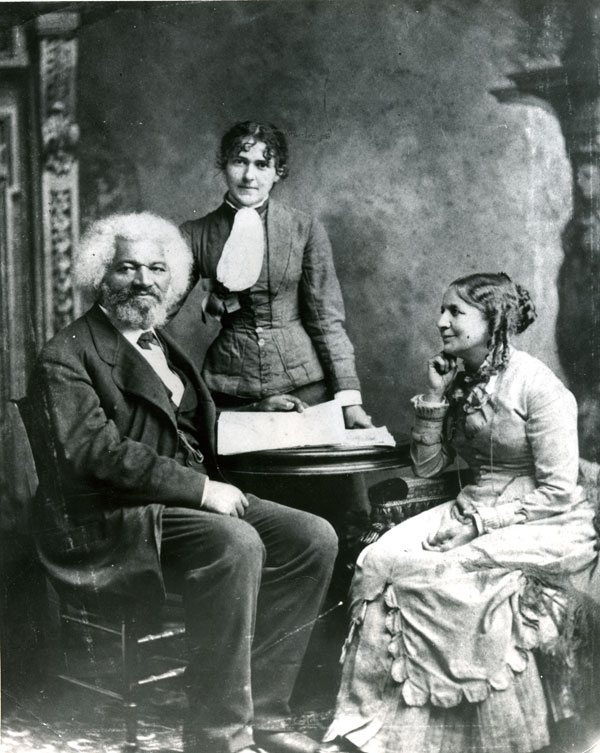

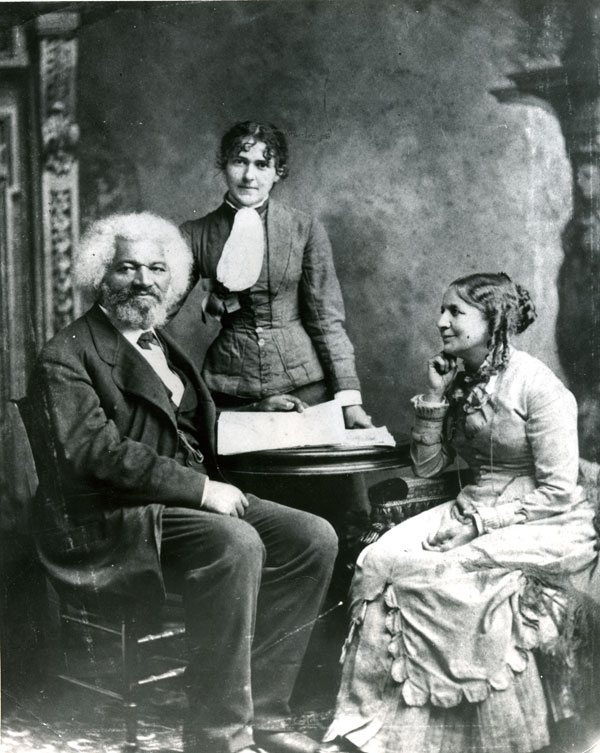

Two years after Anna's death in 1882, Douglass married the white feminist Helen Pitts (1838-1903). Both families resented the inter-racial marriage, to which Douglass remarked:

"This proves I am impartial. My first wife was the color of my mother and the second, the color of my father."

foreground: Douglass & Helen Pitts Douglass

background: Eva Pitts, Helen's

sister

Douglass's autobiographies refer only occasionally and briefly to his family. This absence of personal references is frustrating today but unremarkable for a public figure of his time. Neither of his wives is directly represented or quoted.

Douglass mentions his difficulty in arranging his children's equal education and his sons' careers as soldiers for the Union in the Civil War or as aides in his publishing ventures.

In a brief digression Douglass reports his grief at the death of his last child Annie in 1847 while he is overseas: "news reached me from home of the death of my beloved daughter. Annie, the light and life of my house. Deeply distressed by this bereavement, and acting upon the impulse of the moment, regardless of the peril, I at once resolved to return home, and took the first outgoing steamer" (LT part 2, ch. 10).

![]()

Review of My Bondage and My Freedom & The Life & Times of Frederick Douglass

In the parlance of modern blogging: "We read it so you don't have to."

But why for this seminar? Many of us are already teaching or will teach, and all of us will continue reading as a way of exploring identity in a changing world.

Ongoing pedagogical effort to combine two strands of reading in instruction of literature:

1. Traditional canon: great authors writing timeless works, mostly representing identities and values of elite or dominant cultures

2. Expanded canon of multicultural and women's writings, more or less representing voices and identities of marginal or oppressed people(s).

Previous solutions, variously practiced in public or private schools: maintain traditional canon of "excellence" while devoting spare time or specialized classes to "representative" or "under-represented" authors, texts, and traditions.

Emergent solution: With familiarity and practice teaching, borders between "excellence" and "representative" become dialogues or exchanges.

Comparable phenomenon: old racial-identity borders are increasingly crossed now, but research shows such boundaries were always crossed, as in Douglass's and Jacobs's genetic backgrounds.

As population demographics grow more diverse, text-selections respond to who's reading and who's teaching.

My generation was mostly educated in Old Canon but began reading and integrating New Canon. For subsequent generations, both canons are normal and dialogues natural.

Specific scholarly and teaching purposes—what do with reading and knowledge?

Dr. White's personal-professional motives in reading:

I've been teaching Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass in one course or another for 20+ years. Since students often like Narrative, I repeatedly mentioned existence of Douglass's later installments but never read them myself. Conscience twinged more each time I said this, so when a 2012 student (Jason Kimbrell) proposed a research journal on Douglass's My Bondage & My Freedom (Investigating Frederick Douglass: A Research Journal, I took the opportunity.

Overcoming a professional danger for dominant-culture scholars teaching multicultural literature: Since my generation's reading was very monocultural, knowing even a little of multicultural or minority literature imparted an aura of expertise for someone my age. But a scholar learns to call his own bluff and to demand continuing reading and research. What sufficed a generation or decade ago sounds stale or canned by now. Just like in my 20s, completing a difficult reading assignment refreshed my sense of progress and opened to new possibilities for learning and research.

For class:

1. Extend knowledge of literary history and major authors (most serious readers know Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass but most non-specialists stop there, less than halfway through his eventful and productive life);

discuss, evaluate how a writer grows across career (Bondage & Freedom written after ten years more of reading and writing; Life & Times written comparatively later in life, after Civil War and Reconstruction)

2. Apply to today's discussion question on Romanticism and Realism.

3. Develop research for presentation or publication

![]()

1. Extend knowledge of literary history and major authors (most serious readers know Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass but most non-specialists stop there, less than halfway through his eventful and productive life)

Discuss, evaluate how a writer grows across career (Bondage & Freedom written after ten years more of reading and writing; Life & Times written comparatively later in life, after Civil War and Reconstruction)

Slave narrative as one of two unique literary contributions by North America to World literature--the other being the captivity narrative.

Of hundreds of slave narratives published from the 1700s to the early 20th century, Douglass's is widely regarded as the genre's masterpiece. Douglass's Narrative is now widely read in American high schools and colleges as a foundational text of African American literature and an essential text of the American Renaissance.

Altogether Douglass wrote three versions of his life story—the second two expanding the contents of their predecessors:

-

1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (app. 100 pages in Library of America compendium edition)

-

1855 My Bondage and My Freedom (app. 350 pages)

-

1881, 1892 The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (app. 600 pages)

Development / relationship of three autobiographies:

Each later volume contains the previous volume(s); the autobiographies are not sequential (like Maya Angelou's 5 memoirs beginning with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings) but incremental.

What's new and what changes from Narrative of Life of Frederick Douglass (1845, app. 100 pages) to My Bondage and My Freedom (1855, app. 300 pages)?

Biggest surprise: Not that much completely new material—only 4 new chapters at end describing tours of England, various meetings and events. Douglass writes these chapters as though readers are already familiar with these activities. Their appeal is mostly journalistic, as they mention famous people and comment on issues of the day, but they lack the depth and representational detail of the chapters on slavery, a situation he had to represent and explain to Northern readers.

Also at end of Bondage and Freedom, an Appendix of speeches and letters, surprisingly good—increasing awareness that Douglass made his living as a professional public speaker.

In Bondage & Freedom Douglass describes his need to go beyond simple storytelling to analysis, explanation, meaning in his public speaking as a former slave:

Changes in his story of slavery and escape:

![]() Adds details, contexts, sets up events to have more meaning. Cf. family story you later

hear again.

Adds details, contexts, sets up events to have more meaning. Cf. family story you later

hear again.

![]() Straight story of events >

intellectual and spiritual autobiography, the life of a mind (cf. Henry Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Cardinal Newman, Dorothy Day).

Straight story of events >

intellectual and spiritual autobiography, the life of a mind (cf. Henry Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Cardinal Newman, Dorothy Day).

![]() Pleasure in Douglass's explication of stages of

thought and learning + agreeable conclusions

Pleasure in Douglass's explication of stages of

thought and learning + agreeable conclusions

Adds Christian thematics. Contrast appendix to Narrative, which acknowledges but doesn't resolve controversy over his treatment of "Southern religion." Bondage & Freedom more completely incorporates his own religious growth and sensitivities. (Example of praying after fight with Covey)

But not just intellectual or bookish pleasures.

Characters are added, introduced, or more fully sketched, and their personalities influence the themes in development. (Characters essential to literary aesthetics.)

First & later descriptions of Sophia Auld teaching Frederick how to read. (chapter 10)

10B Chesapeake Bay scene in Narrative; reproduced intact in My Bondage & My Freedom, ch. 15

10D Sandy + fight with Covey; compare ch. 17 of Bondage & Freedom

adds Hughes and Caroline to Covey scene

resistance of Henry: internal characterization, intellectualize, thematize + general enhancement of action

Outcome from familiarity with My Bondage and My Freedom:

Literary excellence of My Bondage and My Freedom means it could be assigned for advanced students instead of Narrative (but class-time would require two weeks instead of one).

![]()

What's new and what changes from Narrative of Life of Frederick Douglass (1845, app. 100 pages) and My Bondage and My Freedom (1855, app. 300 pages) to Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, 1892; app. 600 pages).

![]() First half of Life and Times is nearly a copy of Bondage and

Freedom, with a few paragraphs dropped or added here and there; since

slavery and persecution is over, he includes more names of people in North who

helped him when he arrived there after escaping.

First half of Life and Times is nearly a copy of Bondage and

Freedom, with a few paragraphs dropped or added here and there; since

slavery and persecution is over, he includes more names of people in North who

helped him when he arrived there after escaping.

![]() One major addition: includes

description of escape itself.

Now that slavery has ended, he can freely discuss escape routes, who helped him,

etc. The escape is expertly written, but interestingly its actual events occur

without much drama or peril. The result is less Romantic than the results of

one's imagination when the information was withheld.

One major addition: includes

description of escape itself.

Now that slavery has ended, he can freely discuss escape routes, who helped him,

etc. The escape is expertly written, but interestingly its actual events occur

without much drama or peril. The result is less Romantic than the results of

one's imagination when the information was withheld.

![]() Greater sense of Douglass's career as a public speaker; cf. television

talking head or "public intellectual"

Greater sense of Douglass's career as a public speaker; cf. television

talking head or "public intellectual"

Comparable to political autobiographies today, Life and Times gives an inside look at current events across a very eventful lifetime.

Life and Times Parts 1 & 2 (app. 500 pages) completed in 1881.

In 1891-2 Douglass adds Part 3 concerning the 1880s till time of writing: mostly journalistic reports of his actions with political institutions, appointments, and campaigns, climaxing in his controversial tenure as Consul-General to Haiti. (A U.S. Navy commander intervened to disrupt his diplomacy to establish a U.S. coaling base in Haiti.)

Douglass wrote for contemporaries, not for later readers

Information on John Brown may be invaluable to historians, but he also provides information, representations, and language from Lincoln, Stowe, and other historical figures.

from Section Two, Chapters 11 & 12: Descriptions of Lincoln

Support of women's rights

Life and Times, part 2, ch. 18. [These passage follow a review of women leaders in the anti-slavery moment:]

There were many such to greet me and welcome me to my newly-found heritage of freedom. They met me as a brother, and by their kind consideration did much to make endurable the rebuffs I encountered elsewhere. . . .

Observing woman's agency, devotion, and efficiency in pleading the cause of the slave, gratitude for this high service early moved me to give favorable attention to the subject of what is called "woman's rights" and caused me to be denominated a woman's-rights man. I am glad to say that I have never been ashamed to be thus designated. Recognizing not sex nor physical strength, but moral intelligence and the ability to discern right from wrong, good from evil, and the power to choose between them, as the true basis of republican government, to which all are alike subject and all bound alike to obey, I was not long in reaching the conclusion that there was no foundation in reason or justice for woman's exclusion from the right of choice in the selection of the persons who should frame the laws, and thus shape the destiny of all the people, irrespective of sex. . . .

If intelligence is the only true and rational basis of government, it follows that that is the best government which draws its life and power from the largest sources of wisdom, energy, and goodness at its command. . . .

But it is not my purpose to argue the question here, but simply to state in a brief way the ground of my espousal of the cause of woman's suffrage. I believed that the exclusion of my race from participation in government was not only a wrong, but a great mistake, because it took from that race motives for high thought and endeavor and degraded them in the eyes of the world around them. Man derives a sense of his consequence in the world not merely subjectively, but objectively. If from the cradle through life the outside world brands a class as unfit for this or that work, the character of the class will come to resemble and conform to the character described. To find valuable qualities in our fellows, such qualities must be presumed and expected. I would give woman a vote, give her a motive to qualify herself to vote, precisely as I insisted upon giving the colored man the right to vote; in order that she shall have the same motives for making herself a useful citizen as those in force in the case of other citizens. In a word, I have never yet been able to find one consideration, one argument, or suggestion in favor of man's right to participate in civil government which did not equally apply to the right of woman.

Spelling of Douglass:

As with Poe, teaching Frederick Douglass always faces the inevitable problem of initiating students into how spell these authors' names in an unusual but accurate way.

Not Edgar Allen Poe, but Edgar Allan Poe

Not Frederick Douglas, but Frederick Douglass

Now, having read Life and Times, Douglass shows himself aware that "Douglass" is a misspelling of its source . . . and so generations of students have an additional but unnecessary struggle:

Narrative 11.22 I gave Mr. Johnson the privilege of choosing me a name, but told him he must not take from me the name of "Frederick." I must hold on to that , to preserve a sense of my identity. Mr. Johnson had just been reading the "Lady of the Lake," [poem by Sir Walter Scott, 1810] and at once suggested that my name be "Douglass." From that time until now I have been called "Frederick Douglass" . . . .

Life and Times part 2, ch. 2: Once initiated into my new life of freedom and assured by Mr. Johnson that I need not fear recapture in that city, a comparatively unimportant question arose, as to the name by which I should be known thereafter, in my new relation as a free man. The name given me by my dear mother was no less pretentious and long than Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. I had, however, while living in Maryland, disposed of the Augustus Washington, and retained only Frederick Bailey. Between Baltimore and New Bedford, the better to conceal myself from the slave-hunters, I had parted with Bailey and called myself Johnson; but finding that in New Bedford the Johnson family was already so numerous as to cause some confusion in distinguishing one from another, a change in this name seemed desirable. Nathan Johnson, mine host, was emphatic as to this necessity, and wished me to allow him to select a name for me. I consented, and he called me by my present name,--the one by which I have been known for three and forty years,—Frederick Douglass. Mr. Johnson had just been reading the "Lady of the Lake," and so pleased was he with its great character that he wished me to bear his name. Since reading that charming poem myself, I have often thought that considering the noble hospitality and manly character of Nathan Johnson, black man though he was, he, far more than I, illustrated the virtues of the Douglas of Scotland. Sure am I that if any slave-catcher had entered his domicile with a view to my recapture, Johnson would have been like him of the "stalwart hand."

![]()

2. Apply to today's discussion questions on Romanticism and Realism.

1. What problems arise in discussing genres like slave narratives in terms of literary styles like Romanticism or Realism? What challenges, problems, or advantages from discussing such texts as literature rather than cultural or historical documents?

Question 2. What may be inherently Romantic about the symbols and values of the slave narrative? How may its structure or sequence resemble the romance narrative?

Question 3. What realities or realistic descriptions fall outside Romantic style or violate the romance narrative?

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl 21.5

from Section Two, Chapter One: Escape from Slavery

![]()

3. Develop research for presentation or publication

As with Research Journal or Research Reports, equipped for a next move of a conference presentation or publication.

Combine new knowledge with previous knowledge, make comparisons.

Frederick Douglass, c. 1818-95 repeated updates and enlargement of autobiography |

Walt Whitman, 1819-92 continual updates and enlargement of Leaves of Grass (collection of poetry) |

Comparison: Walt Whitman's poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which originally appears in 1855

Conclusion: Leaves of Grass

1855, 1856, 1860, 1867, 1871–72, and 1881. Others add in the 1876, 1888–89, and 1891-92 (the "deathbed edition").

1855: 12 poems, 95 pages

1891-2 "deathbed edition": 400+ poems

quotation from LG: Who holds this book holds a man

or Henry James, New York Edition

Louise Erdrich, Love Medicine 1984; revised and expanded 1993; re-revised 2009

appeals: combines mainstream author (Whitman) with minority author (Douglass) under unifying formal interpretation

![]()

370 (ch. 24) 1845 "pamphlet" (irony)

How does Bondage & Freedom change from Narrative?

Adds details, contexts, sets up events so they have more meaning. Cf. family story that you later learn more of.

Straight story of events > intellectual autobiography, the life of a mind; cf. Henry Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Cardinal Newman: pleasure in following Douglass's explication of stages of though and learning + agreeable conclusions

In Bondage & Freedom Douglass describes this need to go beyond simple storytelling to analysis, explanation, meaning in his public speaking as a former slave:

Adds Christian thematics; contrast appendix to Narrative

But not just intellectual or bookish pleasures.

Characters are added, introduced, or more fully sketched, and their personalities influence the themes in development. (Characters essential to literary aesthetics.)

First & later descriptions of Sophia Auld teaching Frederick how to read. (chapter 10)

10B Chesapeake Bay scene in Narrative; reproduced intact in My Bondage & My Freedom, ch. 15

10D Sandy + fight with Covey; compare ch. 17 of Bondage & Freedom

adds Hughes and Caroline to Covey scene

resistance of Henry: intellectualize, thematize + general enhancement of action

from Ch. 25: Various Incidents

Questions:

What learn about "school reading" and "advanced reading?"

What do your students need? What do you need?

What about how a writer or thinker grows and learns and changes style?

![]()

Highlights from The Life & Times of Frederick Douglass

from Section Two, Chapter One: Escape from Slavery

from Section Two, Chapters 11 & 12: Descriptions of Lincoln

notes 407 speech in England 1846: love religion of love to God and man, golden rule

I hate the slaveholding, the woman-whipping, the mind-darkening, the soul-destroying religion that exists in the southern states fo America

412 Letter to His Old Master

413 anniversary of my emancipation

419 heard some of the old slaves talking of their parents having been stolen from Africa

414-15 We want to live in the land of our birth

416 think of dear children

417 my own dear sisters and only brother, 418 seize your own lovely daughter (domestic: family as moral)

431 what to the Slave is the Fourth of July; Rochester 5 July 1852

The Slavery Party 440 Pierce represents slavery party

Bondage & Freedom notes

230 "Abolition" interpreted; language for meaning

change: Severe > Sevier

cf. experience of Deerslayer epilogue

184-5 quotes Narrative < "sketching my life"

184 visits Ireland during famine of 1845-6

259 cf. Equiano as perpetual separation / insecurity (x-proslavery)

BUT narration / description > generalization

259? + situates Bay scene (contrast 1st time writer)

265 master-slave dynamic + 266 names dynamic

267-9 Chesapeake Bay Scene reproduced

google "better day coming"

270 x-victim > truthful impression

brutalized > converse (Covey)

276 slaveholders dread labor

human-property; master-slave

284-5 adds Hughes and Caroline to Covey scene

298 textuality! Columbian Orator + 305

300 digressing

300 met several slaves . . . once my scholars . . . obtained their freedom

303 spirit-devouring thralldom

304 chain metaphor; cf. Jacobs

natural and inborn right

305 reading on human rights = intertextuality

319 resistance of Henry: intellectualize, thematize + general enhancement of action

language still familiar from my world

new version as sequel + remake

321 dialogue; cf. Col Orator

cf. lawyer making case

325 scandal of 1 Christian selling another to Georgia traders (represses action)

326 ch. 20 "Well! dear reader, . . . "

Was he helped? possible answer: he's so charismatic that even owners want him to like them; cf presence to Denjel, MJ, Tupac, Ice Cube

330 slavery > clas conflict

336 city: colored persons who could instruct me

cf. Franklin: East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society

349 The dreams of my childhood and the purposes of my adulthood were now fulfilled

355 Columbian Oragor

355 plain, Quaker dress

356 "among the Quakers"

366 a confession of very low origin

367 now reading and thinking; x-narrate > denounce

370 1845 "pamphlet" (irony)

379 Joseph Sturge of society of Friends (1793-1859)

381-2 religious controversy; Free Church of Scotland

393 children at north: the old black man

396 color prejudice not natural but social

401 Dickens's Notes on America

402 Whittier

devastating combination of politeness and acerbity

413 deserted at escape

414 slaves talk of Africa

414-5 We want to live in the land of our birth . . . .

417 grandmother

429 living God, natural and revealed

447 but one such man

449 HBStowe

449 Pierpont, North Star (John Pierpont, 1789-1866)

450 one man

451 every new-born white babe

danger: slave narrative = only story possible? (no reference to slavery in title of Life and Times)

cf. Leaves of Grass as multiple expanding editions with appendices

chapters > titles

cf. Narrative to Mary Rowlandson Narrative

reading three autobios as tracing growth of writer's mind; extraordinary trial of growth of human mind at somewhat late stage of development

possible to imagine reading non-sequentially? increasingly

analysis, detail, characters, rhetoric give NLFD readers a reason to buy this book too; cf. music fans

more detail risks particularizing, "granular"

character sketches

Great Farm songs: more context

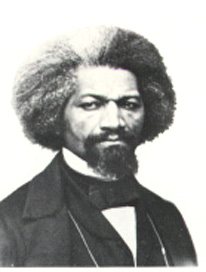

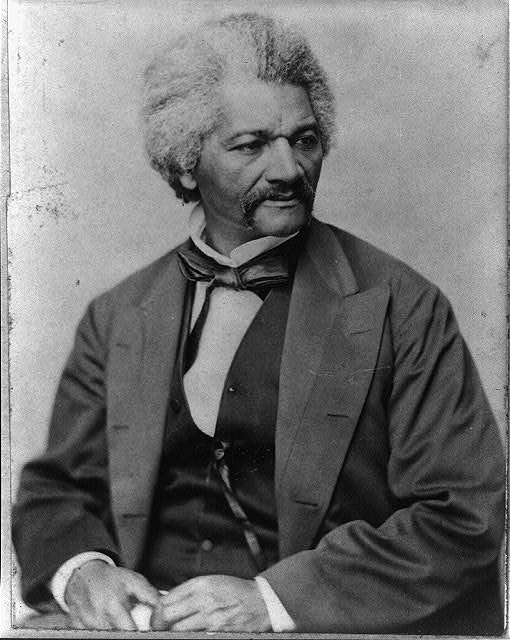

Photos of Douglass (to be arranged)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

from Ch. 25: Various Incidents