|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

George Orwell Shooting an Elephant 1936 |

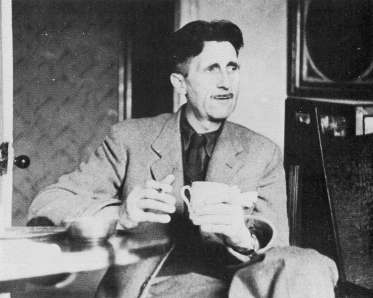

George Orwell (b. Eric Arthur Blair, 1903-1950) |

|

|

George Orwell is best-known for the dystopian-allegorical novels Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Animal Farm (1945), which remain staples of secondary and college reading lists. Orwell also endures as a writer and thinker with wide appeal. Both conservative and liberal commentators cite him as an incisive authority, sympathetic to the down and out but skeptical of official tyranny. Two texts by Orwell feature prominently in colonial and postcolonial literature, both critical of imperialism in Orwell's understated or ironical style: Burmese Days (1934, 1935), Orwell's first novel, is a fictional representation of events during the author's five years as a police officer in Burma (now renamed Myanmar), which was then part of India and the British Empire. "Shooting an Elephant" (1936) . . . (see below) Colonized by the British in the 1800s, Burma gained independence as a separate nation in 1948, when the British colony of India was partitioned to West Pakistan (now Pakistan), India, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and Burma. A military junta officially ruled Burma from 1962 to 2010, when free elections were held, though the military maintains oppressive influence. In 1989 the military government officially changed the nation's name from Burma to Myanmar, but either name remains contested. |

|

|

|

![]()

Discussion questions:

1. As formal genre, how does the personal essay resemble or vary from the novel or fiction?

2. How does Orwell's essay indicate or symbolize the "self-other" in terms of Europe and "East?" Where and how successfully are these symbolic divisions crossed, and how? What symbols (or sets of symbols) include both self and other?

3. If colonial literature posits the "self" as European "white man" and the "other" as Eastern, Oriental, Asian, or non-European "natives," how do the two different parties appear to and affect each other? (Put another way, how much does non-verbal social pressure effect a dialogue?)

4. How does the narrator both criticize and exemplify "Imperialism?" The narrator diffidently fills the role of the savior / oppressor of colonial / postcolonial fiction. How does the narrator exceed or vary this characterization? Consider irony.

5. What does the rifle signify in the European-Eastern dialogue? Preview effect of Crusoe's rifle on Friday.

![]()

Shooting an Elephant

(1936)

[1]

In Moulmein, in lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people—the only

time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me. I

was sub-divisional police officer of the town, and in an

aimless, petty kind of

way anti-European feeling was very bitter. No one had the guts to raise a riot,

but if a European woman went through the bazaars alone somebody would probably

spit betel juice over her dress. As a police officer I was an obvious target and

was baited whenever it seemed safe to do so. When a nimble Burman tripped me up

on the football [soccer] field and the referee (another Burman) looked the other way, the

crowd yelled with hideous laughter. This happened more than once. In the end the

sneering yellow faces of young men that met me everywhere, the insults hooted

after me when I was at a safe distance, got badly on my nerves. The young

Buddhist priests were the worst of all. There were several thousands of them in

the town and none of them seemed to have anything to do except stand on street

corners and jeer at Europeans.

[2]

All this was perplexing and upsetting. For

at that time I had already made up my mind that imperialism was an evil thing

and the sooner I chucked up my job and got out of it the better.

Theoretically—and secretly, of course—I was all for the Burmese and all against

their oppressors, the British. As for the job I was doing, I hated it more

bitterly than I can perhaps make clear. In a job like that you see the dirty

work of Empire at close quarters. The wretched prisoners huddling in the

stinking cages of the lock-ups, the grey, cowed faces of the long-term convicts,

the scarred buttocks of the men who had been flogged with bamboos—all these

oppressed me with an intolerable sense of guilt. But I could get nothing into

perspective. I was young and ill-educated and I had had to think out my problems

in the utter silence that is imposed on every Englishman in the East. I did not

even know that the British Empire is dying, still less did I know that it is a

great deal better than the younger empires that are going to supplant it. All I

knew was that I was stuck between my hatred of the empire I served and my rage

against the evil-spirited little beasts who tried to make my job impossible.

With one part of my mind I thought of the British Raj as an unbreakable tyranny,

as something clamped down, in saecula saeculorum [forever

and ever], upon the will of prostrate

peoples; with another part I thought that the greatest joy in the world would be

to drive a bayonet into a Buddhist priest's guts. Feelings like these are the

normal by-products of imperialism; ask any Anglo-Indian official, if you can

catch him off duty.

[3] One day

something happened which in a roundabout way

was enlightening. It was a tiny incident in itself, but it gave me a better

glimpse than I had had before of the real nature of imperialism—the real motives

for which despotic governments act. Early one morning the sub-inspector at a

police station the other end of the town rang me up on the phone and said that

an elephant was ravaging the bazaar. Would I please come and do something about

it? I did not know what I could do, but I wanted to see what was happening and I

got on to a pony and started out. I took my rifle, an old 44 Winchester and much

too small to kill an elephant, but I thought the noise might be useful in

terrorem [warning]. Various Burmans stopped me on the way and told me about the elephant's

doings. It was not, of course, a wild elephant, but a tame one which had gone

"must." [<musth or rut] It had been chained up, as tame elephants always are when their attack

of "must" is due, but on the previous night it had broken its chain and escaped.

Its mahout [driver], the only person who could manage it when it was in that state, had

set out in pursuit, but had taken the wrong direction and was now twelve hours'

journey away, and in the morning the elephant had suddenly reappeared in the

town. The Burmese population had no weapons and were quite helpless against it.

It had already destroyed somebody's bamboo hut, killed a cow and raided some

fruit-stalls and devoured the stock; also it had met the municipal rubbish van

and, when the driver jumped out and took to his heels, had turned the van over

and inflicted violences upon it.

[4]

The Burmese sub-inspector and some

Indian constables were waiting for me in the quarter where the elephant had been

seen. It was a very poor quarter, a labyrinth of squalid bamboo huts, thatched

with palmleaf, winding all over a steep hillside. I remember that it was a

cloudy, stuffy morning at the beginning of the rains

[monsoon season]. We began questioning the

people as to where the elephant had gone and, as usual, failed to get any

definite information. That is invariably the case in the East; a story always

sounds clear enough at a distance, but the nearer you get to the scene of events

the vaguer it becomes. Some of the people said that the elephant had gone in one

direction, some said that he had gone in another, some professed not even to

have heard of any elephant. I had almost made up my mind that the whole story

was a pack of lies, when we heard yells a little distance away. There was a

loud, scandalized cry of "Go away, child! Go away this instant!" and an old

woman with a switch in her hand came round the corner of a hut, violently

shooing away a crowd of naked children. Some more women followed, clicking their

tongues and exclaiming; evidently there was something that the children ought

not to have seen. I rounded the hut and saw a man's dead body sprawling in the

mud. He was an Indian, a black Dravidian coolie [South

Indian laborer], almost naked, and he could not

have been dead many minutes. The people said that the elephant had come suddenly

upon him round the corner of the hut, caught him with its trunk, put its foot on

his back and ground him into the earth. This was the rainy season and the ground

was soft, and his face had scored a trench a foot deep and a couple of yards

long. He was lying on his belly with arms crucified and head sharply twisted to

one side. His face was coated with mud, the eyes wide open, the teeth bared and

grinning with an expression of unendurable agony. (Never tell me, by the way,

that the dead look peaceful. Most of the corpses I have seen looked devilish.)

The friction of the great beast's foot had stripped the skin from his back as

neatly as one skins a rabbit. As soon as I saw the dead man I sent an orderly to

a friend's house nearby to borrow an elephant rifle. I had already sent back the

pony, not wanting it to go mad with fright and throw me if it smelt the

elephant.

[5] The orderly came back in a few minutes with a rifle and five

cartridges, and meanwhile some Burmans had arrived and told us that the elephant

was in the paddy fields below, only a few hundred yards away. As I started

forward practically the whole population of the quarter flocked out of the

houses and followed me. They had seen the rifle and were all shouting excitedly

that I was going to shoot the elephant. They had not shown much interest in the

elephant when he was merely ravaging their homes, but it was different now that

he was going to be shot. It was a bit of fun to them, as it would be to an

English crowd; besides they wanted the meat. It made me vaguely uneasy. I had no

intention of shooting the elephant—I had merely sent for the rifle to defend

myself if necessary—and it is always unnerving to have a crowd following you. I

marched down the hill, looking and feeling a fool, with the rifle over my

shoulder and an ever-growing army of people jostling at my heels. At the bottom,

when you got away from the huts, there was a metalled

[gravel] road and beyond that a

miry waste of paddy fields a thousand yards across, not yet ploughed but soggy

from the first rains and dotted with coarse grass. The elephant was standing

eight yards from the road, his left side towards us. He took not the slightest

notice of the crowd's approach. He was tearing up bunches of grass, beating them

against his knees to clean them and stuffing them into his mouth.

[6] I had

halted on the road. As soon as I saw the elephant I knew with perfect certainty

that I ought not to shoot him. It is a serious matter to shoot a working

elephant—it is comparable to destroying a huge and costly piece of machinery—and

obviously one ought not to do it if it can possibly be avoided. And at that

distance, peacefully eating, the elephant looked no more dangerous than a cow. I

thought then and I think now that his attack of "must"

[rut] was already passing off;

in which case he would merely wander harmlessly about until the mahout [driver] came back

and caught him. Moreover, I did not in the least want to shoot him. I decided

that I would watch him for a little while to make sure that he did not turn

savage again, and then go home.

[7]

But at that moment I glanced round at the

crowd that had followed me. It was an immense crowd, two thousand at the least

and growing every minute. It blocked the road for a long distance on either

side. I looked at the sea of yellow faces above the garish clothes—faces all

happy and excited over this bit of fun, all certain that the elephant was going

to be shot. They were watching me as they would watch a conjurer about to

perform a trick. They did not like me, but with the magical rifle in my hands I

was momentarily worth watching. And suddenly I realized that I should have to

shoot the elephant after all. The people expected it of me and I had got to do

it; I could feel their two thousand wills pressing me forward, irresistibly. And

it was at this moment, as I stood there with the rifle in my hands, that I first

grasped the hollowness, the futility of the white man's dominion in the East.

Here was I, the white man with his gun, standing in front of the unarmed native

crowd—seemingly the leading actor of the piece; but in reality I was only an

absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind. I

perceived in this moment that when the white man turns tyrant it is his own

freedom that he destroys. He becomes a sort of hollow, posing dummy, the

conventionalized figure of a sahib [Urdu "sir" for

addressing Europeans; cf. Swahili Bwana]. For it is the condition of his rule that he

shall spend his life in trying to impress the "natives," and so in every crisis

he has got to do what the "natives" expect of him. He wears a mask, and his face

grows to fit it. I had got to shoot the elephant. I had committed myself to

doing it when I sent for the rifle. A sahib has got to act like a sahib; he has

got to appear resolute, to know his own mind and do definite things. To come all

that way, rifle in hand, with two thousand people marching at my heels, and then

to trail feebly away, having done nothing—no, that was impossible. The crowd

would laugh at me. And my whole life, every white man's life in the East, was

one long struggle not to be laughed at.

[8]

But I did not want to shoot the

elephant. I watched him beating his bunch of grass against his knees, with that

preoccupied grandmotherly air that elephants have. It seemed to me that it would

be murder to shoot him. At that age I was not squeamish about killing animals,

but I had never shot an elephant and never wanted to. (Somehow it always seems

worse to kill a large animal.) Besides, there was the beast's owner to be

considered. Alive, the elephant was worth at least a hundred pounds; dead, he

would only be worth the value of his tusks, five pounds, possibly. But I had got

to act quickly. I turned to some experienced-looking Burmans who had been there

when we arrived, and asked them how the elephant had been behaving. They all

said the same thing: he took no notice of you if you left him alone, but he

might charge if you went too close to him.

[9] It was perfectly clear to me

what I ought to do. I ought to walk up to within, say, twenty-five yards of the

elephant and test his behavior. If he charged, I could shoot; if he took no

notice of me, it would be safe to leave him until the mahout

[elephant-driver] came back. But also

I knew that I was going to do no such thing. I was a poor shot with a rifle and

the ground was soft mud into which one would sink at every step. If the elephant

charged and I missed him, I should have about as much chance as a toad under a

steam-roller. But even then I was not thinking particularly of my own skin, only

of the watchful yellow faces behind. For at that moment, with the crowd watching

me, I was not afraid in the ordinary sense, as I would have been if I had been

alone. A white man mustn't be frightened in front of "natives"; and so, in

general, he isn't frightened. The sole thought in my mind was that if anything

went wrong those two thousand Burmans would see me pursued, caught, trampled on

and reduced to a grinning corpse like that Indian up the hill. And if that

happened it was quite probable that some of them would laugh. That would never

do.

[10] There was only one alternative. I shoved the cartridges into the

magazine and lay down on the road to get a better aim. The crowd grew very

still, and a deep, low, happy sigh, as of people who see the theatre curtain go

up at last, breathed from innumerable throats. They were going to have their bit

of fun after all. The rifle was a beautiful German thing with cross-hair sights.

I did not then know that in shooting an elephant one would shoot to cut an

imaginary bar running from ear-hole to ear-hole. I ought, therefore, as the

elephant was sideways on, to have aimed straight at his ear-hole, actually I

aimed several inches in front of this, thinking the brain would be further

forward.

[11] When I pulled the trigger I did not hear the bang or feel the

kick—one never does when a shot goes home—but I heard the devilish roar of glee

that went up from the crowd. In that instant, in too short a time, one would

have thought, even for the bullet to get there, a mysterious, terrible change

had come over the elephant. He neither stirred nor fell, but every line of his

body had altered. He looked suddenly stricken, shrunken, immensely old, as

though the frightful impact of the bullet had paralysed him without knocking him

down. At last, after what seemed a long time—it might have been five seconds, I

dare say—he sagged flabbily to his knees. His mouth slobbered. An enormous

senility seemed to have settled upon him. One could have imagined him thousands

of years old. I fired again into the same spot. At the second shot he did not

collapse but climbed with desperate slowness to his feet and stood weakly

upright, with legs sagging and head drooping. I fired a third time. That was the

shot that did for him. You could see the agony of it jolt his whole body and

knock the last remnant of strength from his legs. But in falling he seemed for a

moment to rise, for as his hind legs collapsed beneath him he seemed to tower

upward like a huge rock toppling, his trunk reaching skyward like a tree.

He

trumpeted, for the first and only time. And then down he came, his belly towards

me, with a crash that seemed to shake the ground even where I lay.

[12] I got

up. The Burmans were already racing past me across the mud. It was obvious that

the elephant would never rise again, but he was not dead. He was breathing very

rhythmically with long rattling gasps, his great mound of a side painfully

rising and falling. His mouth was wide open—I could see far down into caverns of

pale pink throat. I waited a long time for him to die, but his breathing did not

weaken. Finally I fired my two remaining shots into the spot where I thought his

heart must be. The thick blood welled out of him like red velvet, but still he

did not die. His body did not even jerk when the shots hit him, the tortured

breathing continued without a pause. He was dying, very slowly and in great

agony, but in some world remote from me where not even a bullet could damage him

further. I felt that I had got to put an end to that dreadful noise. It seemed

dreadful to see the great beast Lying there, powerless to move and yet powerless

to die, and not even to be able to finish him. I sent back for my small rifle

and poured shot after shot into his heart and down his throat. They seemed to

make no impression. The tortured gasps continued as steadily as the ticking of a

clock.

[13] In the end I could not stand it any longer and went away. I heard

later that it took him half an hour to die. Burmans were bringing dash and

baskets even before I left, and I was told they had stripped his body almost to

the bones by the afternoon.

[14]

Afterwards, of course, there were endless

discussions about the shooting of the elephant. The owner was furious, but he

was only an Indian and could do nothing. Besides, legally I had done the right

thing, for a mad elephant has to be killed, like a mad dog, if its owner fails

to control it. Among the Europeans opinion was divided. The older men said I was

right, the younger men said it was a damn shame to shoot an elephant for killing

a coolie, because an elephant was worth more than any damn Coringhee coolie

[laborer from town of Coringa in southern India]. And

afterwards I was very glad that the coolie had been killed; it put me legally in

the right and it gave me a sufficient pretext for shooting the elephant. I often

wondered whether any of the others grasped that I had done it solely to avoid

looking a fool.

Indian Elephant

article comparing Berkeley police pepper-spray incident to "Shooting an Elephant"