|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

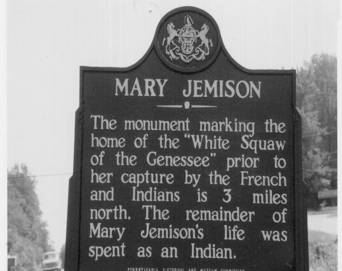

selections from NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF MRS. MARY JEMISON

|

|

[1.1]

. . . On the account of the great length

of time that has elapsed since I was separated from my parents and friends, and

having heard the story of their nativity only in the days of my childhood, I am

not able to state positively, which of the two countries, Ireland or Scotland,

was the land of my parents’ birth and education. It, however, is my impression,

that they were born and brought up in

[1.2]

My Father's name was Thomas Jemison, and my mother's before her marriage with

him, was Jane Erwin. Their affection for each other was mutual . . . .

[1.3]

Resolved to leave the land of their nativity they removed from their residence

to a port in Ireland, where they . . . set sail for this country, in the year

1742 or 3 on board the ship Mary William, bound to Philadelphia, in the state of

Pennsylvania.

[1.4]

The intestine

[internal]

divisions, civil wars, and ecclesiastical

[institutional-church]

rigidity and domination that prevailed those days, were the causes of their

leaving their mother country [for] a

home in the American wilderness, under the mild and temperate government of the

descendants of William Penn

[i.e., Quakers]

. . . .

[1.5]

In

[1.6]

In the course of their voyage I was born . . . .

[1.7]

Excepting my birth, nothing remarkable occurred to my parents on their passage,

and they were safely landed at

[1.8]

During this period my mother had two sons, between whose ages there was a

difference of about three years: the oldest was named Matthew, and the other

Robert.

[1.9]

. . . Our mansion

[house]

was a little paradise. . . . Frequently I dream of those happy days: but . . .

they have left me to be carried through a long life, dependent for the little

pleasures of nearly seventy years, upon the tender mercies of the Indians!

In the spring of 1752, and through the

succeeding seasons, the stories of Indian barbarities inflicted upon the whites

in those days, frequently excited in my parents the most serious alarm for our

safety.

[These paragraphs describe events of the French and Indian War, 1754-63; as in

Narrative of Mary Rowlandson

[King Philip's War],

compare descriptions of Indians to modern terrorists.]

[1.10]

The next year the storm gathered faster; many murders were committed; and many

captives were exposed to meet death in its most frightful form, by having their

bodies stuck full of pine splinters, which were immediately set on fire, while

their tormentors, exulting in their distress, would rejoice at their agony!

[ritual fire-torture, practiced by some

Iroquois on their enemies]

[1.11]

In 1754, an army for the protection of the settlers, and to drive back the

French and Indians, was raised from the militia of the colonial governments, and

placed (secondarily) under the command of

Col. George Washington. . . . The

French and Indians . . . grew more and more terrible. The death of the whites,

and plundering and burning their property, was apparently their only object . .

. .

[1.12]

The winter of 1754-5 was as mild as a common fall season, and the spring

presented a pleasant seed time, and indicated a plenteous harvest. . . .

[1.13]

But alas! how transitory are all human affairs! . . . In one fatal day our

prospects were all blasted; and death, by cruel hands, inflicted upon almost the

whole of the family.

[1.14]

On a pleasant day in the spring of 1755 . . . I was sent to a neighbor's house,

a distance of perhaps a mile, to procure a horse and return with it the next

morning. I went as I was directed. I was

out of the house in the beginning of the evening, and saw a sheet widespread

approaching towards me, in which I was caught (as I have ever since believed)

and deprived of my senses! The family soon found me on the ground, almost

lifeless, (as they said,) took me in . . . till day-break, when my senses

returned, and I soon found myself in good health, so that I went home with the

horse very early in the morning.

[1.15]

The appearance of that sheet, I have ever considered as a forerunner of the

melancholy catastrophe that so soon afterwards happened to our family

. . . .

![]()

map indicating Scotch-Irish

immigration

(not to scale; Northern Ireland at bottom; American Atlantic

ports at left)