|

Craig White's Literature Courses Terms / Themes

Scots-Irish see also History of Scots-Irish Immigration |

|

The Scotch-Irish are a major ethnic source of the USA's dominant culture, but their relationship with the dominant culture may be distanced or conflicted, to the extent that their behavior sometimes (and increasingly) resembles that of an emergent minority group that defines itself by grievances or exploitation.

For details on Scotch-Irish immgration, see History of Scots-Irish Immigration, but briefly they may be regarded as a third wave of immigration from the British Isles:

Wave 1 (or 2): 1620s-30s Puritan immigration from eastern England to Massachusetts Bay or "New England"; establishment of middle-class commonwealth with spiritual equality and values additional to wealth.

Wave 2 (or 1): 1607 (Jamestown) but mostly 1640s-50s "Cavalier" immigration from southern England to Virginia and other mid-Atlantic colonies; aristocratic society of large plantations with African American slaves instead of European peasants, plus some middle-class or working-class whites with smaller holdings.

Wave 3: 1700s Scotch-Irish immigration from Northern England, Scotland, and Ireland to interiors of mid-Atlantic and southern colonies, especially to foothills and Appalachian Mountains, where they served as buffer between Indians and East Coast elites.

If the earlier two waves create the "two sets of Founders" who establish orderly communities for organizing American life, the Scotch-Irish constitute a somewhat disorderly people who live restlessly under the status quo and make it respond to their needs.

If among the early European settlers the first two waves establish the systems, the Scotch-Irish increasingly become identified with "the people" (as in white people); e.g., the Okies in John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath.

"The people" alternately put their faith in and feel betrayed by the USA's governments and leadership, insisting they're the real America, and to a great extent they have succeeded in creating America in their own image.

John Wayne

(1907-79), American actor

of Scottish, Scotch-Irish, Irish, & English

descent

|

Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) World War 2 military cult film |

The greatest challenge to describing and analyzing the Scotch-Irish immigrant culture or ethnicity is that the terms of analysis are often set by the earlier settlers.

Thus the Scotch-Irish identify racially with the earlier settler elites of New England and Virginia but may express less commitment to education, literacy, and universal rights. (Such differences may be class differences as well as ethnic differences.)

In balance, the Scotch-Irish became indispensable to the eastern establishment, filling in the back-country areas and fighting Indians, and later supplying the largest ethnic contingent of soldiers to America's armed forces.

How the Scotch-Irish may resemble a minority:

Dependence on extended family

Traditions of personal and family honor (cf. "respect" for African Americans)

As with minority groups, mistrust of centralized authority and suspicion that any stranger expressing interest in your welfare is really out to get you.

Cultivation of alternative media, e.g. Fox News, talk radio.

Distinct musical traditions (Country & Western music derived from Scotch-Irish border ballads)

Early marriage and age-at-first-birth

(More development of this page for next week's class.)

Texts

David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford UP, 1989.

Rory Fitzpatrick, God's Frontiersmen: The Scots Irish Epic.

Joe Bageant, Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from the Class War. Crown, 2007.

possible offering of course as "Whiteness / Dominant Culture studies"--if course is dedicated to it, students may commit to study

Possible texts:

Winter's Bone

Bastard Out of Carolina

Born Fighting

Thunder Road

Of Plymouth Plantation and Exodus

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit

a military novel?

Country & Western music?

![]()

Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America (2004)

by James Webb

NY: Broadway, 2004.

|

|

Jim Webb (James H. Webb, Jr., b. 1946), a Virginian of Scots-Irish descent and the USA's most decorated Vietnam War Marine, became Secretary of Navy in the 1980s and later a respected novelist of Vietnam War (Fields of Fire [1978] + 5 other military novels) as well as a screenwriter and movie producer. In 2006 Webb was elected U. S. Senator from Virginia but chose not to run for re-election in 2012. (In 2006 Webb ran and won as a Democrat after being a Republican for most of his adult life. He strongly opposed President George W. Bush's war policies.) |

Foreword, xiii-xix

xiv. . . . in the context of recent American politics this is the story of the core culture around which Red State America has gathered and thrived. Its tendency toward egalitarian traditions, mistrust of central authority, frequent combativeness, and an odd indifference to wealth make the Scots-Irish a uniquely values based culture, whose historical journey has been marked by fiercely held loyalties to leaders who will not betray their ideals.

2 Scots-Irish presidents fit profile:

-

Ronald Reagan (1980-88)--successful Cold-War president personifying rugged individualism

-

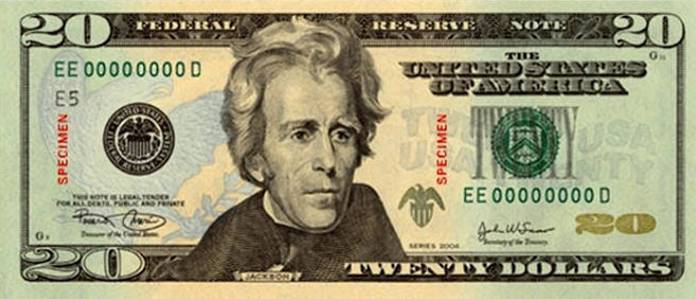

Andrew Jackson (1828-1836)--Indian fighter, Cherokee Trail of Tears

Andrew Jackson (1767-1845; President 1828-1836)

-

Indian fighter & hero of Battle of New Orleans at end of War of 1812

-

de-authorized national bank

-

founded modern Democratic Party

-

first U.S. President not from Atlantic Coast (Tennessee)

-

defied U.S. Supreme Court in forcing Southeast Indians on Trail of Tears

xv They [the Scots-Irish] were the original Jacksonians (indeed, Andrew Jackson defined them to America), and were among the strongest of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Democrats. Decades later they formed the core of the Reagan Democrats, and with that pendulum swing went the votes of the South over to the Republicans. Karl Rove understood them completely even if he did not overtly identify them ethnically, fashioning many of the emotional and values-based issues that consolidated the power of George W. Bush.

As the twentieth century moved forward toward the twenty-first, the impact of this culture grew, particularly in the military as well as in rural and blue-collar America.

Chapter 1. Big Mocassin Gap

4 [Celtic tribes of middle Europe] . . . did not retreat. But they refused to recognize leadership beyond their local tribes and thus would not become a nation. And they had a permeating discontent that caused the more determined of them to keep pushing, every generation, a little bit farther into the wild unknown.

5 . . . they became the British Empire's greatest voyagers, . . . settling in odd places all around the world. And for that splinter of them that became my people, the Scots-Irish, this meant the Appalachian Mountains, their first stop on their way to creating a way of life that many would come to call, if not American, certainly the defining fabric of the South and the Midwest as well as the core character of the nation's working class.

8 The slurs stick to me . . . . Rednecks. Trailer-park trash. Racists. Cannon fodder. My ancestors. My people. Me.

8 . . . in a society obsessed with multicultural jealousies, those who cannot articulate their ethnic origins are doomed to a form of social and political isolation. My culture needs to rediscover itself, and in so doing to regain its power to shape the direction of America.

Among leading themes:

-

Most Confederate soldiers were Scots-Irish

-

Plurality of Union soldiers and all wars since are Scots-Irish

As dominant culture:

Invisible, unmarked, very little attention, but very important

ethnic customs:

clan mentality, family honor, blood relation (clan = tribe)

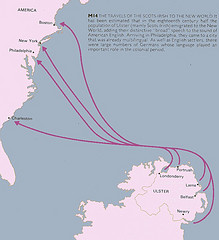

U. of Virginia website on Scots-Irish primarily in America

Scots emigration / immigration to the US (thanks, Carrie)

map juxtaposes Northern Ireland (lower right) with eastern colonial America (upper left)

Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (2012)

"Greater Appalachia was founded in the early eighteenth century by wave upon wave of rough, bellicose settlers from the war-ravaged borderlands of Northern Ireland, northern England, and the Scottish lowlands....these clannish Scots-Irish, Scots, and north English frontiersmen spread across the highland South and on into the southern tiers of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois; the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks; the eastern two-thirds of Oklahoma; and the hill country of Texas, clashing with Indians, Mexicans and Yankees as they migrated."

"Their ancestors had weathered 800 years of nearly constant warfare....Living

amid constant upheaval, many Borderlanders embraced a Calvinist religious

tradition—Presbyterianism—that held that they were God’s chosen people, members

of a biblical nation sanctified in blood and watched over by a wrathful Old

Testament deity. Suspicious of outside authority of any kind, the Borderlanders

valued individual liberty and personal honor above all else, and were happy to

take up arms to defend either."

![]()

|

|

|

w/ links for the Center for Scotch-Irish Studies, the Journal of Scotch-Irish Studies, and the Scotch-Irish Society

From:

White, Craig [mailto:whitec@uhcl.edu]

Sent: Monday, May 14, 2012 8:24 PM

To: Michael Scoggins;

cntrsis@aol.com;

rmacmast@ufl.edu

Cc: White,

Doris

Subject: Inquiry regarding Scots-Irish immigrant narratives

Dear Mr. Scoggins & Drs. Alexander & MacMaster,

This summer and fall I teach graduate and undergraduate

courses on American Immigrant Literature and wondered if you could help me

identify some possible narratives to include by Scots-Irish or Scotch-Irish

writers.

If interested,

here is a link to my graduate course—the website is currently in reconstruction,

but you’ll get an idea of its range:

http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/LITR/5731im/

The last couple times I’ve taught

this content, I’ve offered tentative instruction on Scots-Irish immigration as a

foundation for the USA’s dominant culture. Normally that identity is illustrated

by literature of the Puritans and Pilgrims. Since my Anglo-Texan

students, largely descended from immigrants from Virginia, Tennessee, and other

Southern states, don’t much recognize Puritan values beyond a certain point,

I’ve become sensitized to including some backgrounds on those immigrants from

the British Isles from whom they’re more likely to be descended,

consulting James Webb’s

Born Fighting and maps to

at least explain the Scots-Irish identity, of which a few of my students prove

nominally aware.

But these

lessons make little impression because I provide no texts for

them to read and react to. The Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary

Jemison (http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/texts/Amerind/Jemison/JemisonNDX.htm)

features some brief references to this background, and I’ve thought of using a

text like Dorothy Allison’s

Bastard Out of Carolina

(1992), which demonstrates some positive and negative traits of this

culture group but never directly mentions the background—a condition that

appears typical of all later texts if only because the Scotch-Irish

identity is so unknown even to those who bear it.

I’ve installed a link to your center and will review your

journal’s contents but thought I’d start my inquiry with you, as you’re bound to

be familiar with some of the frustrations of Scotch-Irish research. Thanks for

any attention to this inquiry and best wishes to your work.

Craig White

![]()

Prof. Craig,

I apologize for the delay in getting back to you. If I am

interpreting your e-mail correctly, you are looking for first-person

accounts by immigrants of Scotch-Irish ancestry or descendants of that group who

provide some insight into their heritage and what it means to be Scotch-Irish,

at least to them. As you have pointed out, there aren’t that many early

first-person accounts that delve specifically into the Scotch-Irish identity. I

can refer you to a few sources that might be helpful in your curriculum, and

hopefully these will lead you to others.

One source that includes

first-person accounts of the Scotch-Irish settlement of the Shenandoah Valley is

Samuel Kercheval, John Jeremiah

Jacob, and Charles James Faulkner, eds.,

A History of the Valley of Virginia

(1833, 1850; 3rd

ed., rev. and extended, Woodstock, VA: W. N. Grabill, 1902). Another

source that might be helpful, at least as regards South Carolina and the

colonial/Revolutionary War era, is Elizabeth Ellet’s three-volume set

The Women of the American

Revolution (New York: Charles

Scribner, 1853-1854, reprinted several times since). Mrs. Ellet

collected the stories of women from all over the eastern seaboard who

were involved in the Revolution, some first hand, some second hand.

Volume 3 of her trilogy contains a large number of oral

history accounts that were collected by Daniel Green Stinson of Chester County,

SC. Stinson was the son of first-generation Scotch-Irish

immigrants who settled in what is now Chester County, SC prior to the

Revolutionary War. Growing up, he heard stories from the original settlers

about their experiences during the colonial and Revolutionary War period, in a

part of the country that was settled almost exclusively by Scotch-Irish

Presbyterians from Ulster (and a smaller number of Scottish Presbyterians from

lowland Scotland). Stinson never published his research, but he

provided his notes to Mrs. Ellet, who edited them and published them in Volume 3

of her trilogy (which she acknowledged in the introduction to that volume).

There are some similar accounts in Volume 1 of the trilogy, but Volume 3 has the

largest number of accounts describing the lives of these women (and by

extension, their sons, daughters, and husbands), and it is an invaluable

resource for studying this particular time period in the Carolina Piedmont.

I would also recommend the

publications of Dr. Grady McWhiney and Dr. David Hackett Fischer,

who drew on a large number of primary sources for their work. McWhiney published

several scholarly articles in the Journal

of Southern History, including

“Celtic Origins of Southern Herding Practices” (Vol. 5, No. 2, May

1985) and he is the author of Cracker

Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South

(Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988). His research is more generally

focused on the overall Celtic ancestry of Southerners, which

includes Scottish, Scotch-Irish, Irish, and Welsh, but it is a

good reference for original source material that includes first-person accounts.

Part 4 of Fischer’s monumental study

Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), is an invaluable as a source of

references for the settlement of the Southern backcountry by immigrants

from northern Britain and northern Ireland. It also includes detailed

descriptions of the various lifeways that were transported from these areas to

the colonial backcountry, including language and speech. The relevant sections

of both books that deal with literature and speech ways would be good references

for your class and would provide leads for further research.

Much of the information regarding the

history and heritage of the Scotch-Irish, at least in the Carolina Piedmont

where I live, is found in the early histories of the Presbyterian Church

and the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church. I would recommend Dr.

George Howe’s History of the Presbyterian Church in

South Carolina, Vol. 1 (Columbia, SC: Duffie and

Chapman, 1870), and Dr. Robert Lathan’s History of

the Associate Reformed Synod of the South

(Harrisburg, PA: published for the author, 1882). Both these books have a wealth

of information on the early settlement of the Southern uplands by

Scotch-Irish Presbyterians and Scottish Presbyterians during the 18th

century, and the religious heritage of their descendants into

the 19th

century.

Much of my own

research relates to the Scotch-Irish settlement of the Carolina upcountry and

their involvement in the Revolution. Many of the primary sources that I have

utilized are military records—state audited accounts, federal

pension applications, and memoirs written by veterans of the war and their

descendants. The memoirs in particular might be useful to you as examples of

writing by Scotch-Irish veterans of the war in the late 18th

and early 19th

centuries. If you are interested, I would refer you to my book

The Day It Rained Militia

(Charleston: The History Press, 2005) as a source for many of these accounts

relating to the Scotch-Irish involvement in the Revolution in the

Carolinas.

I hope this information is helpful.

Please feel free to contact me if I can be of further assistance.

Michael C.

Scoggins

Historian,

Culture & Heritage Museums

Research

Director, Southern Revolutionary War Institute

212 East

Jefferson Street

York, SC 29745

Phone

803.684.3948 X31

Fax

803.684.0230

Shenandoah Valley

David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford UP, 1989.

Rory Fitzpatrick, God's Frontiersmen: The Scots Irish Epic.

Joe Bageant, Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from the Class War. Crown, 2007.

possible offering of course as "Whiteness / Dominant Culture studies"--if course is dedicated to it, students may commit to study

Possible texts:

Winter's Bone

Bastard Out of Carolina

Born Fighting

Thunder Road

Of Plymouth Plantation and Exodus

The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit

a military novel?

Country & Western music?

Colin Woodard, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America (2012)

"Greater Appalachia was founded in the early eighteenth century by wave upon wave of rough, bellicose settlers from the war-ravaged borderlands of Northern Ireland, northern England, and the Scottish lowlands....these clannish Scots-Irish, Scots, and north English frontiersmen spread across the highland South and on into the southern tiers of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois; the Arkansas and Missouri Ozarks; the eastern two-thirds of Oklahoma; and the hill country of Texas, clashing with Indians, Mexicans and Yankees as they migrated."

"Their ancestors had weathered 800 years of nearly constant warfare....Living

amid constant upheaval, many Borderlanders embraced a Calvinist religious

tradition—Presbyterianism—that held that they were God’s chosen people, members

of a biblical nation sanctified in blood and watched over by a wrathful Old

Testament deity. Suspicious of outside authority of any kind, the Borderlanders

valued individual liberty and personal honor above all else, and were happy to

take up arms to defend either."