|

Craig White's Literature Courses Sentimental Stereotype related term: Romantic Racism |

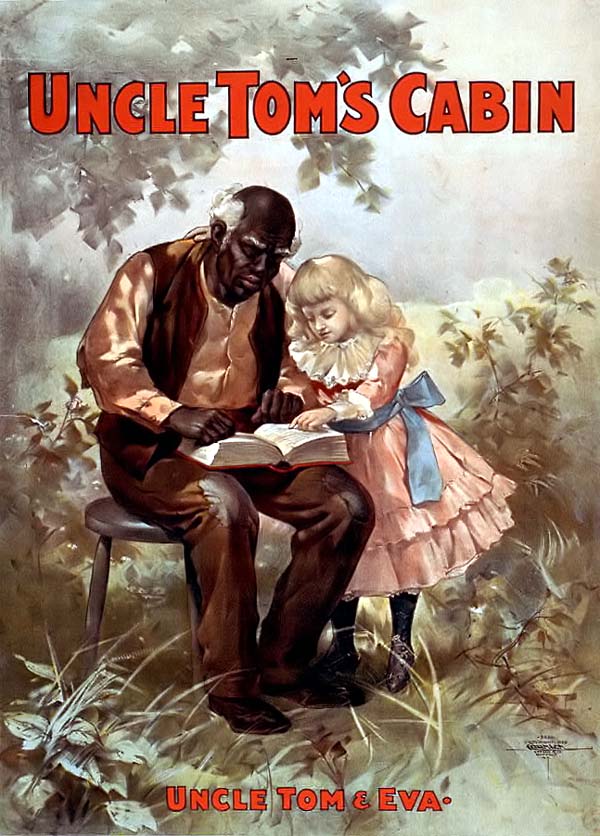

"Uncle Tom" is a familiar "sentimental stereotype" |

"Stereotypes" negatively erase individuality and reinforce racial, class, or gender bias.

"Sentimental," however, may positively signify warm and fuzzy associations like love, family, community, and tradition.

When these two concepts--stereotypes & sentiment--meet, what happens? Is the effect negative, positive, or ambiguous?

Examples below from classic American authors are not equivalent to the worst kinds of racism; usually intended as gentle comedy, their writing demonstrates perceptive or expressive limits that can be interpreted negatively:

-

True to comedy, the human form is diminished rather than enhanced (Aristotle, Poetics, II, V). The joke is shared by the author and audience but not by the subject.

-

Characterization relies on preconceived associations or images that erase individuality or particularity, allowing the audience to think of people as predictable types requiring no consideration of human complexity or suffering.

Contemporary examples:

"The Magical Negro"--coined by filmmaker Spike Lee to describe character archetype / stereotype in recent Hollywood films

Director Spike Lee slams 'same old' black stereotypes in today's films, Yale Bulletin & Calendar, 2 March 2001

"That Old Black Magic" by Christopher John Farley, Time 27 Nov. 2000 on The Legend of Bagger Vance; also explains "Bigot with a Heart of Gold"

TV Tropes on "Magical Negro" & other sentimental stereotypes

TV Tropes on "Whoopi Epiphany Speech"

TV Tropes on "Black Best Friend"

TV Tropes on "Inspirationally Disadvantaged"

TV Tropes on "Magical Native American"

TV Tropes on "Disposable Woman"

TV Tropes on the "Latin Lover"

TV Tropes on "Asian Gal with White Guy"

TV Tropes on "Asian Store Owner"

![]()

Examples from early American literature

Examples from Washington Irving, Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1820):

[Ichabod Crane's class] was suddenly interrupted by the appearance of a negro in tow-cloth jacket and trowsers. a round-crowned fragment of a hat, like the cap of Mercury, and mounted on the back of a ragged, wild, half-broken colt, which he managed with a rope by way of halter. He came clattering up to the school-door with an invitation to Ichabod to attend a merry-making or "quilting-frolic," to be held that evening at Mynheer [mein herr or m'lord] Van Tassel's; and having delivered his message with that air of importance and effort at fine language which a negro is apt to display on petty embassies of the kind, he dashed over the brook, and was seen scampering, away up the Hollow, full of the importance and hurry of his mission.

[Later at Katrina Van Tassel's party] . . . now the sound of the music from the

common room, or hall, summoned to the dance. The musician was an old gray-headed negro, who had been the itinerant

orchestra of the neighborhood for more than half a century. His instrument was

as old and battered as himself. The greater part of the time he scraped on two

or three strings, accompanying every movement of the bow with a motion of the

head; bowing almost to the ground, and stamping with his foot whenever a fresh

couple were to start.

Ichabod prided himself upon his dancing as much as upon his vocal powers. . . . He was the admiration of all the negroes; who, having gathered, of all ages and sizes, from the farm and the neighborhood, stood forming a pyramid of shining black faces at every door and window; gazing with delight at the scene; rolling their white eye-balls, and showing grinning rows of ivory from ear to ear.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, "Sojourner Truth: The Libyan Sibyl" (April 1863)

Her tall form, as she rose up before me, is still vivid to my mind. She was dressed in some stout, grayish stuff, neat and clean, though dusty from travel. On her head she wore a bright Madras handkerchief, arranged as a turban, after the manner of her race. She seemed perfectly self-possessed and at her ease,—in fact, there was almost an unconscious superiority, not unmixed with a solemn twinkle of humor, in the odd, composed manner in which she looked down on me. Her whole air had at times a gloomy sort of drollery which impressed one strangely. . . .

I should have said that she was accompanied by a little grandson of ten years,—the fattest, jolliest wooly-headed little specimen of Africa that one can imagine. He was grinning and showing his glistening white teeth in a state of perpetual merriment, and at this moment broke out into an audible giggle, which disturbed the reverie into which his relative was falling. . . .

from James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans (1826): (In the scene below, Uncas appears as the archetype of "the noble savage")

[6.4] At a little distance in advance stood Uncas, his whole person thrown powerfully

into view.

The travelers anxiously regarded the upright, flexible figure of

the young Mohican, graceful and

unrestrained in the attitudes and movements of nature. Though his person was

more than usually screened by a green and fringed hunting-shirt, like that of

the white man, there was no concealment to his dark, glancing, fearless eye,

alike terrible and calm; the bold outline of his high, haughty

features, pure in their native red;

or to the dignified elevation of his receding forehead, together with all the

finest proportions of a noble head, bared to the generous scalping tuft. It was

the first opportunity possessed by Duncan and his companions to view the marked

lineaments of either of their Indian attendants, and each individual of the

party felt relieved from a burden of doubt, as the proud and determined, though

wild expression of the features of the young warrior forced itself on their

notice. They felt it might be a being partially benighted in the vale of

ignorance, but it could not be one who would willingly devote his rich natural

gifts to the purposes of wanton treachery. The ingenuous Alice gazed at his free

air and proud carriage, as she would have looked upon

some precious relic of the Grecian

chisel

[i.e.,

comparing Uncas to a heroic Greek statue come to life], to which life had been imparted by the intervention of a miracle;

while Heyward, though accustomed to see

the perfection of form which abounds among the uncorrupted natives, openly

expressed his admiration at such an unblemished specimen of the noblest

proportions of man.

|

|

|

![]()