|

Craig White's Literature Courses Gothic Variations esp. in American Literature see also gothic & the grotesque |

>

>

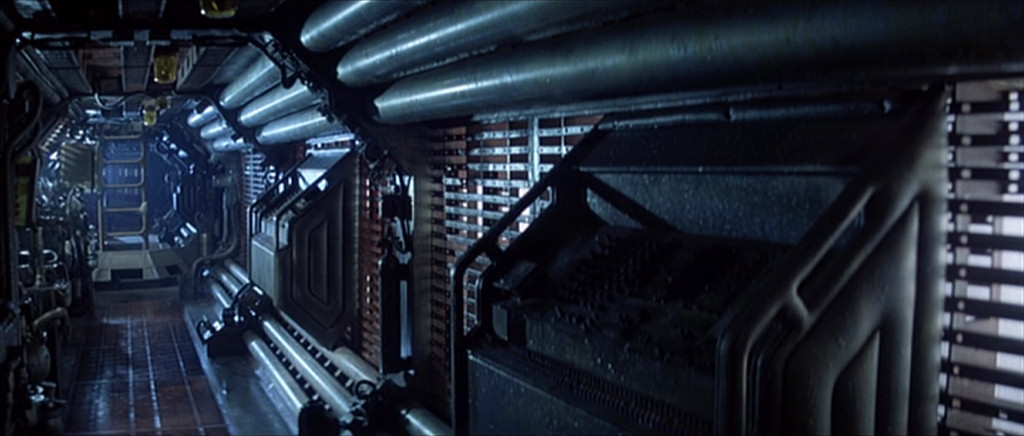

From traditional haunted castle to spaceship Nostromo in Alien (1979) |

Gothic stylings appear so persistently in popular and literary fiction that they must be more than surface phenomena. Instead they are symbols operating in a network of meaning that may be relocated from one situation to another.

The images and texts below indicate some of the variations the gothic has taken in the past two centuries, and before.

![]()

Deep Origins: Hell as prototype of Gothic, Heaven (or Eden) as Antitype

Visions of hell, devils, and demons, with Lucifer as the original Byronic hero: proud, rebellious, attractive, dangerous to know. As the gothic develops, such imagery becomes secularized but may still evoke the supernatural.

As with the fair lady-dark lady counterparts, a vision of Hell requires a complementary vision of Heaven whose parts oppose in terms of color codes, moral values, hygiene, etc.

|

|

In contrast to Hell's

disorder and darkness, Heaven in this popular art-print |

|

|

|

![]()

European Gothic: Haunted House & Haunted Mind

(sometimes haunted family or culture)

(in American literature, chiefly Poe)

Texts:

Edgar Allan Poe, The Fall of the House of Usher; William Wilson; The Raven

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rationale for European haunted house as mind: just as a house has rooms that remain locked because of past crimes and unquiet spirits (perhaps with connecting secret passages), the mind closes off or represses traumas, obsessions, fixations, other sources of disquiet.

Thus the haunted house corresponds to the haunted mind.

According to Freud, repressed fears never stay repressed, just as in the gothic the past like the dead does not stay buried. Correspondingly, the wrongs or traumas we repress can be awakened or triggered by any number of unexpected symbolic associations.

What the mind represses finds expression in dreams and symbols. Thus the gothic, like a bad dream, expresses fears we repress and either resolves anxiety or shifts blame to "other" culprits.

Young people's current obsession with zombies and other undead sorts like vampires may express their repressed fears of environmental and overpopulation apocalypse, violent unrest, suffering, epidemics, mass die-offs (already happening in animal world), mass-migrations, etc.

(Feel free to blame my Boomer generation, whom big government bought nearly-free public higher education and middle-class subsidies, and who responded by cutting their own taxes and telling Millennials to show character and be heroic like we weren't.)

For more illustrations of haunted house as mind, see Mazes & Labyrinths.

The gothic motif of "twinning" may also be psychological, indicating the divided nature of humanity, as in Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886) and Poe's William Wilson (1839).

Poe's

"House of Usher" as face and eyes that look back at observer. (twinning &

correspondence)

![]()

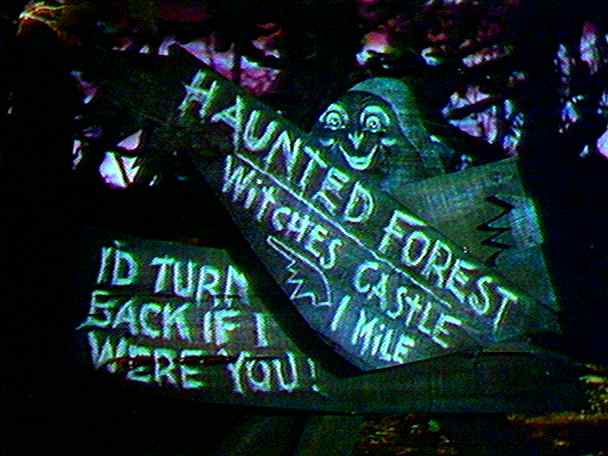

Wilderness Gothic: the Wilderness as site of past crimes & spirits of vengeance

Texts:

Charles Brockden Brown, Edgar Huntly (1799)

Washington Irving, Rip Van Winkle & The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans (1826)

Hawthorne, Young Goodman Brown

|

|

|

|

|

|

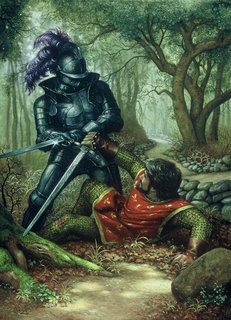

The haunted forest may be traced back to European fairy tales like Hansel & Gretel or tales of knights crossing unknown territories.

|

|

|

medieval manuscript showing knights battling in a wasteland setting

![]()

The Moral, Spiritual, or Puritan Gothic: Hawthorne especially,

but also Jonathan Edwards, Arthur Miller, Shirley

Jackson & others

Texts:

Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter, The Minister's Black Veil; Young Goodman Brown

Jonathan Edwards, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God

Shirley Jackson (1916-1965), "The Lottery," The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

Arthur Miller (1915-2005), The Crucible (1953)

The moral or spiritual gothic resumes some of the moral metaphysics of Western civilization's color code:

![]() light or white equals

goodness and order,

light or white equals

goodness and order,

![]() while darkness or blackness is associated with evil or the

unknown or disorder.

while darkness or blackness is associated with evil or the

unknown or disorder.

Though descended from Puritan stock, Hawthorne was not a religious man in any traditional or institutional sense, but he used gothic imagery or symbolism, including light and dark to create ambiguous modern scenarios in which good and evil, right and wrong, become tragically (and sometimes transcendently) mixed and fused with each other.

Light and dark mix to become shades of gray.

By generating such ambiguity and confusion, Hawthorne avoids fundamentalist moralism and depicts morality as an open-ended process by which humans keep learning what is right and wrong—and become more human by doing so.

|

|

|

|

|

|

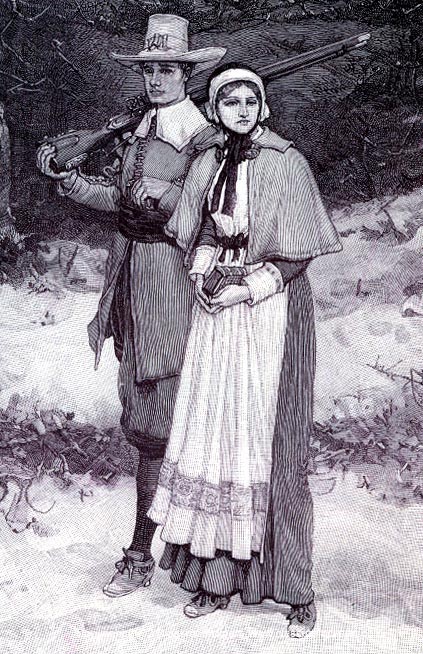

Below:

the

Salem Witch Trials offer a number of gothic

features:

false rumors of

the supernatural, past crimes, unjust deaths

|

|

|

![]()

The Multicultural / Imperial Gothic

Emily Bronte, Wuthering Heights (1847): Byronic character of Heathcliff may be bi-racial. He is brought from the port city of Liverpool, notable for its mixed assemblage of European, Caribbean, and African sailors. He is depicted as vengeful and resentful against his adoptive English family.

Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre (1847): Rochester's first wife Bertha, "the madwoman in the attic," is a Creole from the Caribbean islands. the "Creole" label was ambiguous but increasingly meant mixed-race. The darkness, vitality, and disorder of Bertha's hair is emphasized, as well as her irrational vengeance and wildness.

James Fenimore Cooper, The Last of the Mohicans (1826): The dark lady Cora is the child of the Scottish soldier Munro and a Caribbean woman of partial African descent.

Horror and voodoo movies (esp. from the 1930s) often depict white women characters under threat by Caribbean blacks or Creoles.

American Indians or Middle-Eastern Islamists as demonic terrorists.

![]()

Industrial-Urban Gothic

Texts: Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills (1861)

40]

. . . The rain was

falling heavily, as the woman, pail in hand, emerged from the mouth of the

alley, and turned down the narrow street, that stretched out, long and black . .

. . Here and there a flicker of gas lighted an uncertain space of

muddy footwalk and gutter* . . . .

[41]

Not many even of the inhabitants of a manufacturing town

know the vast *machinery of system by

which the bodies of workmen are governed

. . . . By night and day the work goes on, the unsleeping engines groan and shriek, the

fiery pools of metal boil and surge. Only for a day in the week, in

half-courtesy to public censure, the fires are partially veiled; but as soon as

the clock strikes midnight, the great furnaces break forth with renewed fury,

the clamor begins with fresh, breathless vigor, the engines sob and shriek like

"gods in pain."

[42] As Deborah hurried down through the heavy rain, the noise of these thousand engines [furnaces] sounded through the sleep and shadow of the city like far-off thunder. . . .

[43]

Perhaps, if she had

possessed an artist's eye, the picturesque oddity of the scene might have made

her step stagger less, and the path seem shorter; but to her the mills were only

"summat deilish* to look at by

night."

[44]

The road leading to the mills had been quarried from the

solid rock, which rose abrupt and bare on one side of the cinder-covered road,

while the river, sluggish and black, crept past on the other. The mills for

rolling iron are simply immense tent-like roofs, covering acres of ground, open

on every side. Beneath these roofs Deborah looked in on

a city of fires, that burned hot and

fiercely in the night. Fire in every horrible form: pits of flame waving in the

wind; liquid metal-flames writhing in tortuous streams through the sand; wide

caldrons filled with boiling fire, over which bent ghastly wretches stirring the

strange brewing; and through all, crowds of half-clad men, looking like

revengeful ghosts in the red light, hurried, throwing masses of glittering fire.

It was like a street in Hell. Even Deborah muttered, as she crept through,

"looks like t' Devil's place!" It did,—in more ways than one.

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

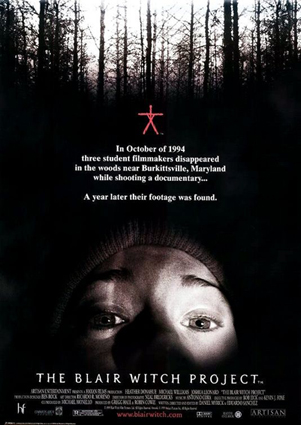

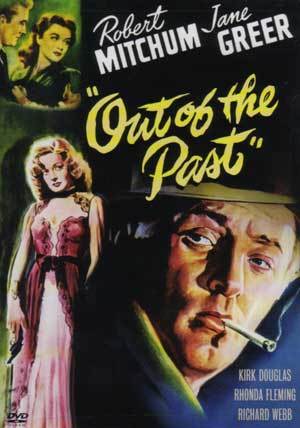

Urban gothic—film noir (dark detective films like The Big Sleep, The Maltese Falcon, Chinatown, Body Heat, LA Confide

Suburban

gothic—Nightmare on Elm Street

![]()

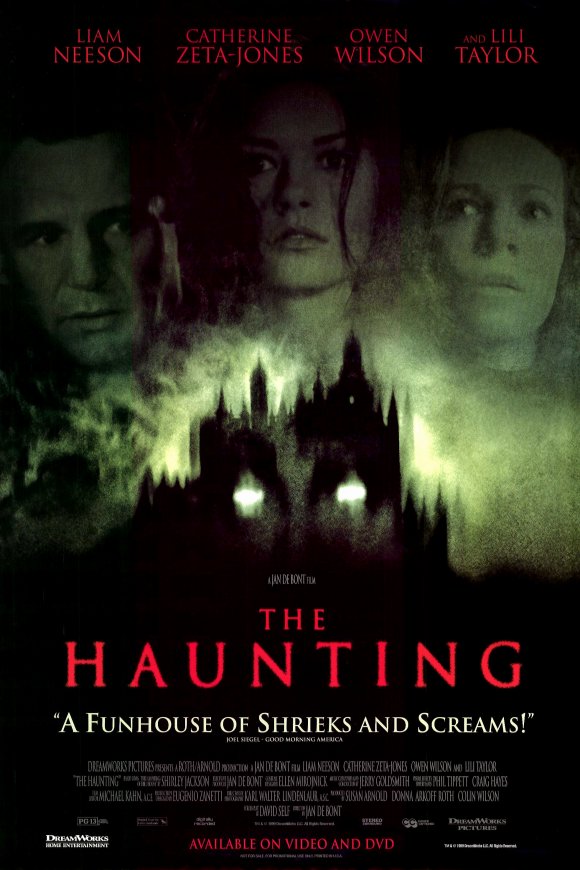

Gothic Architecture

|

|

|

Exterior set of The Haunting (1963)

adapted from Shirley Jackson,

The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

![]()

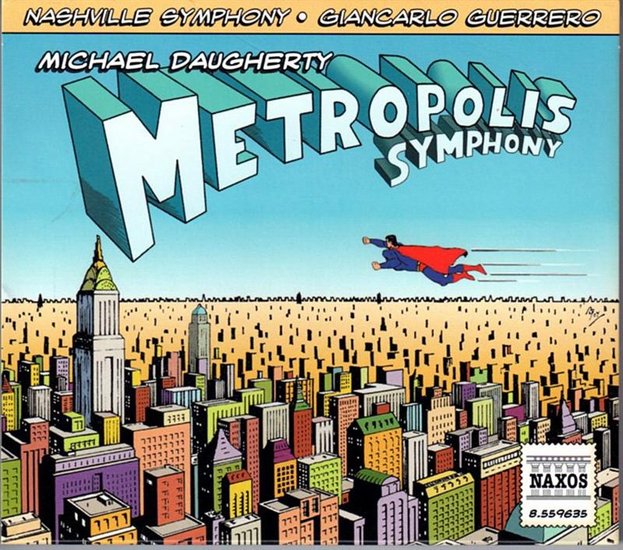

Comic Books / Superheroes:

Superman's Metropolis as daylight city of

progress,

Batman's Gotham City as gothic hell

|

|

Gothan City, from Batman: the Animated Series

|

![]()

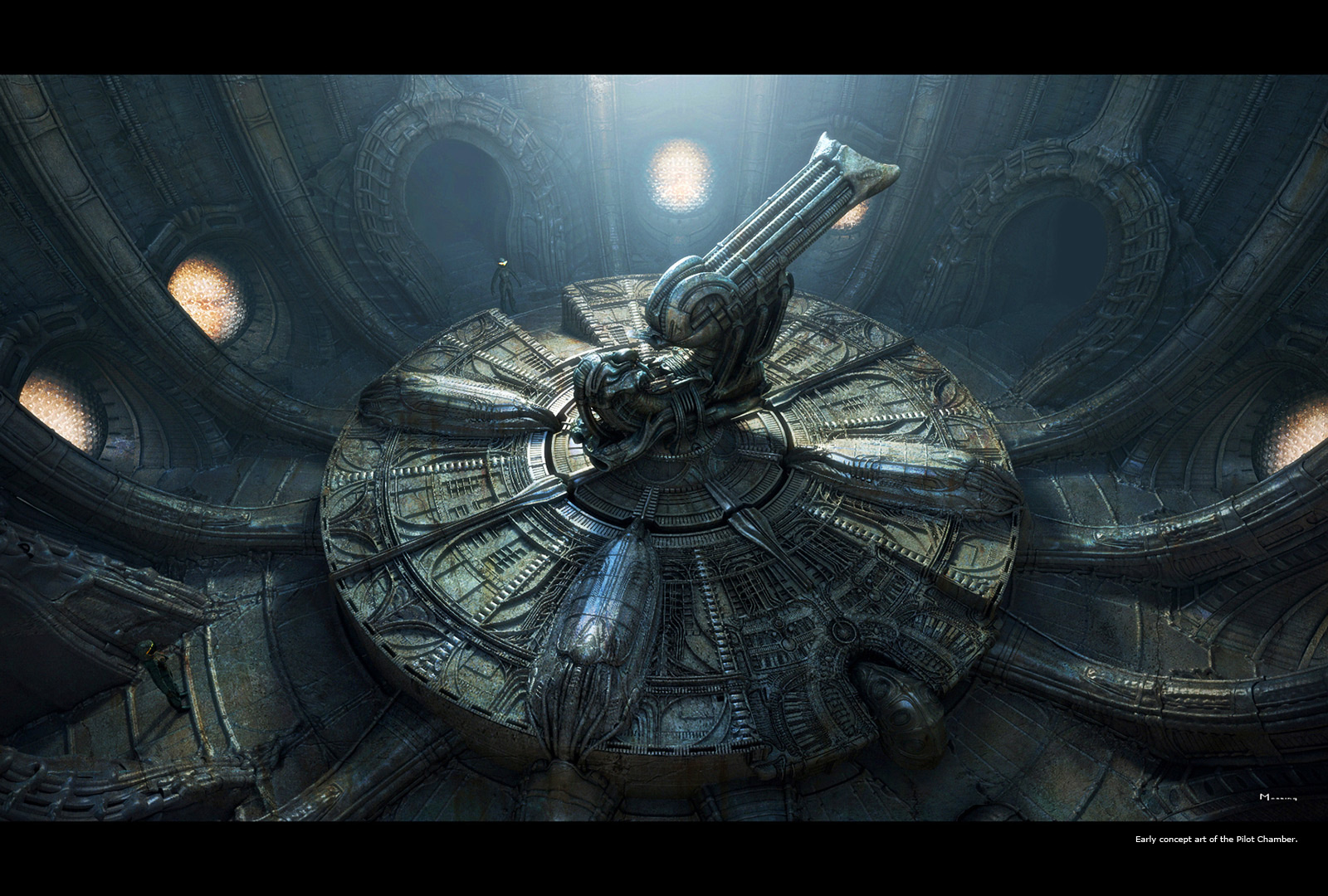

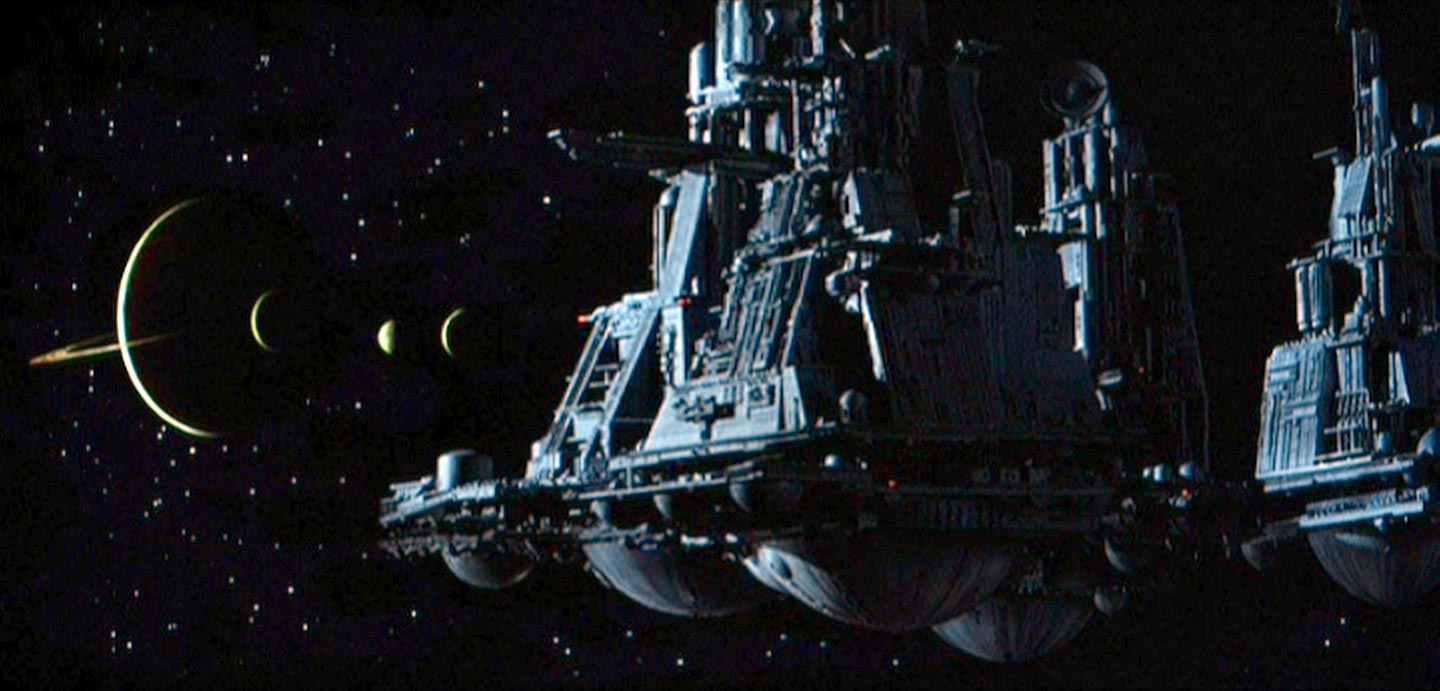

Science Fiction / Extraterrestrial Gothic

Alien (1979)

|

|

|

![]()

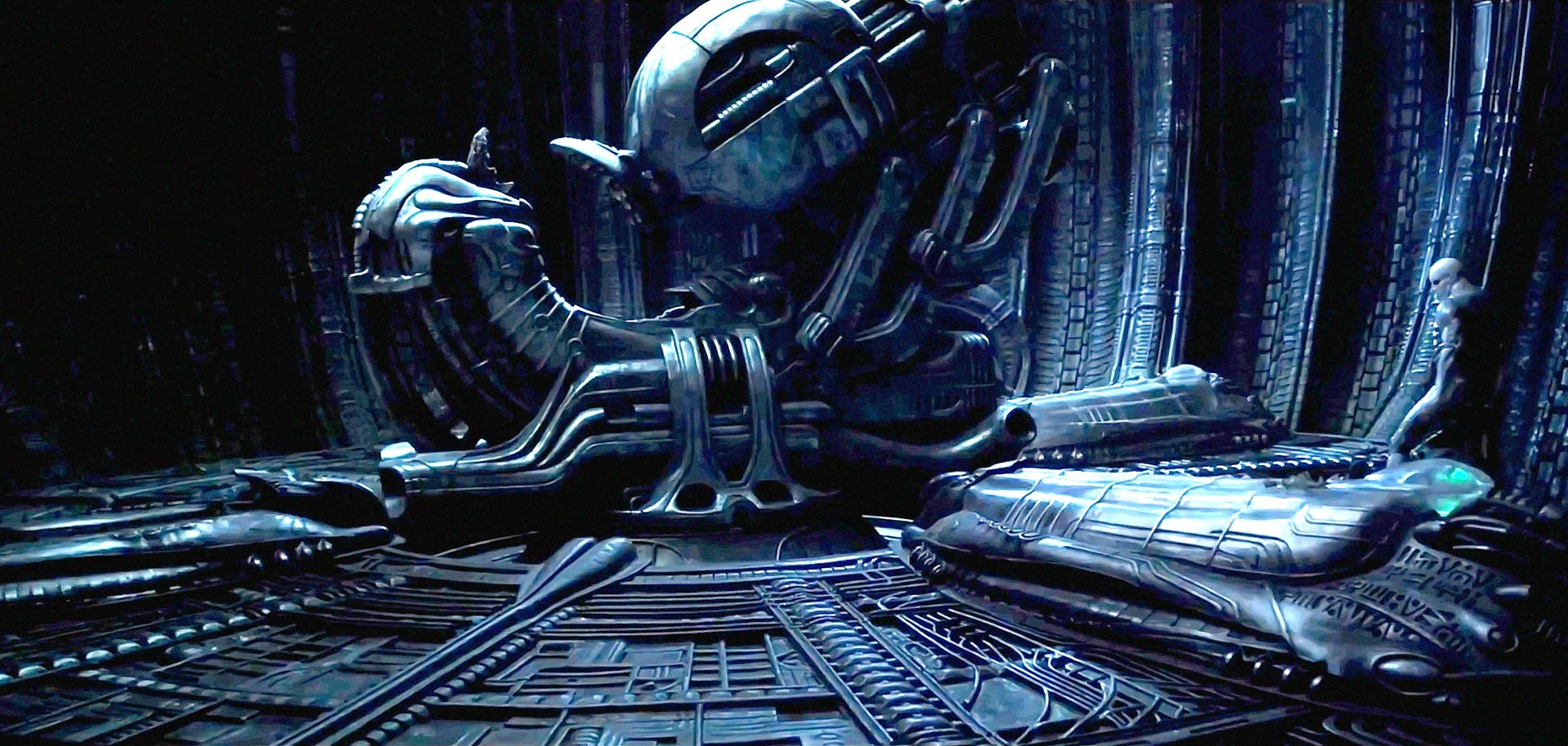

Alien vs. Predator (2004)

![]()

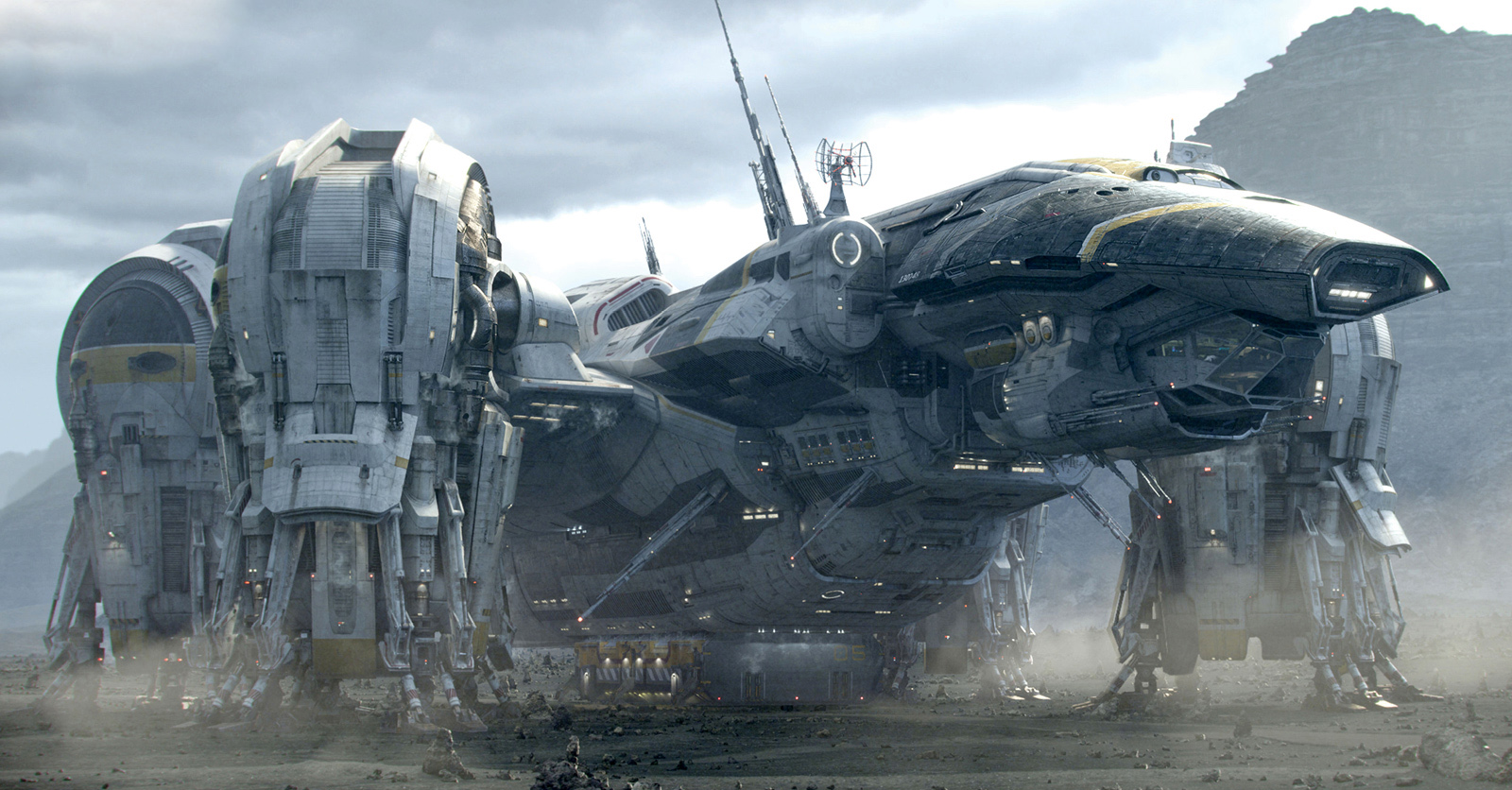

Prometheus (2012)

|

|

|

![]()

Alien Covenant (2017)

|

|

|

gothic as grotesque

![]()

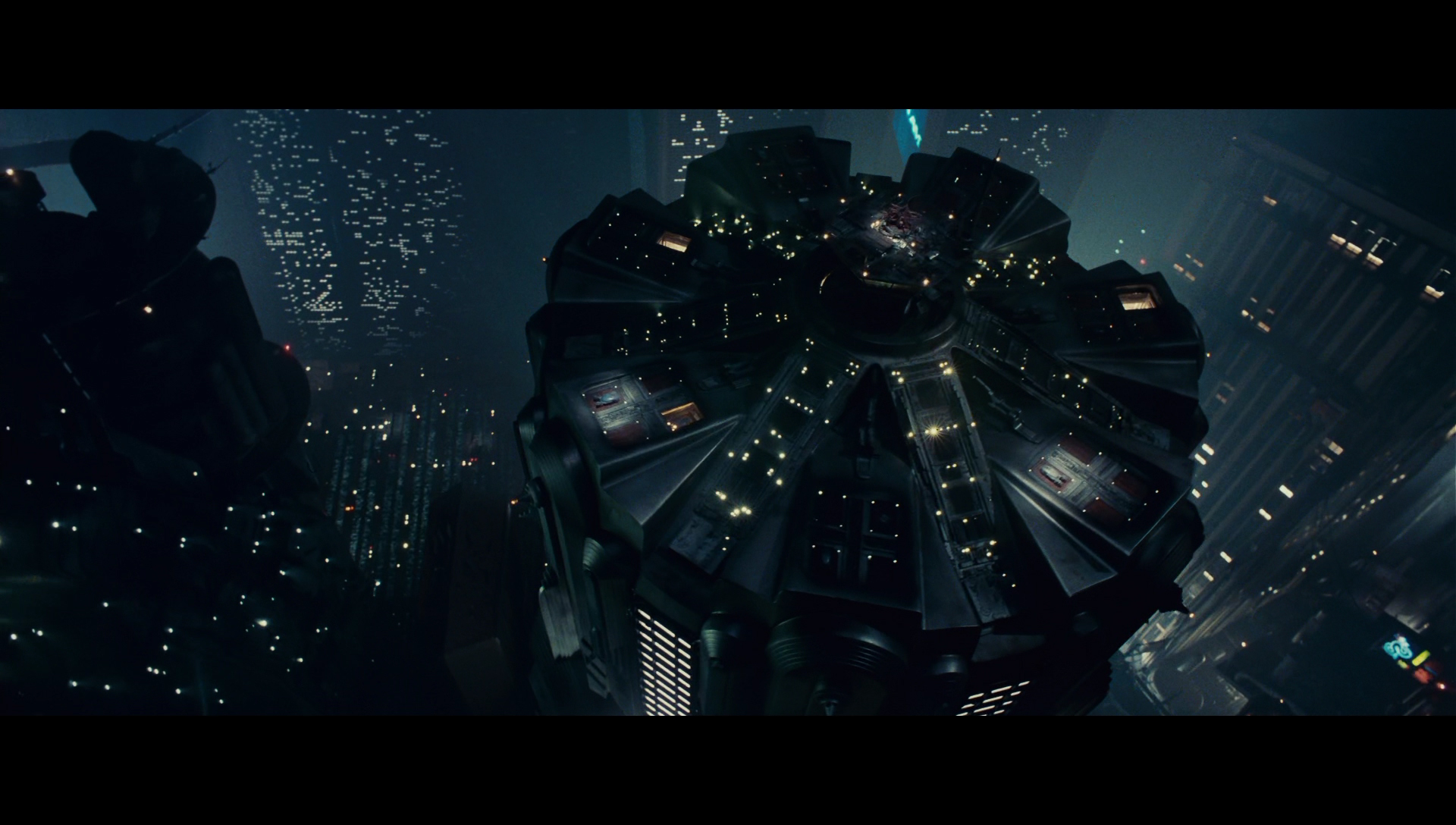

Blade Runner (1982)

|

|

|

![]()

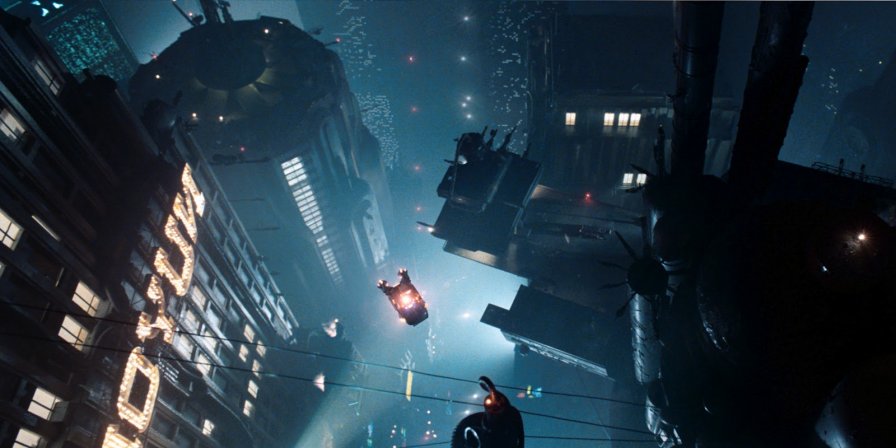

Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

|

|

|