|

Craig White's Literature Courses Historical Backgrounds Uncas (title character of The Last of the Mohicans) |

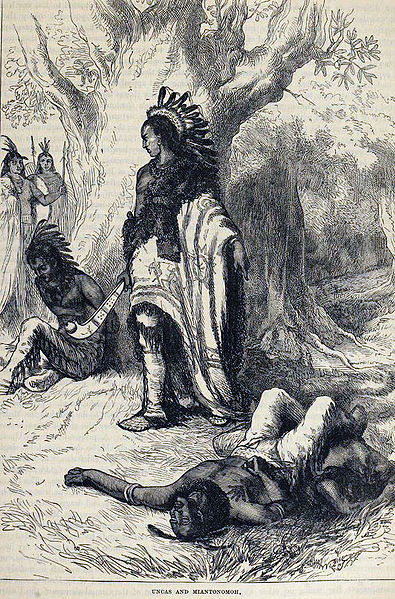

illustration of Uncas in Last of the Mohicans |

The fictional Uncas is title character of James Fenimore Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans (1826), a historical novel of the French and Indian War (1757-63).

Implicit in Cooper's depiction of Uncas's family throughout The Leatherstocking Tales (1823-41): the fictional Uncas's family is descended from a historic Indian leader named Uncas.

The historical Uncas (c. 1588-1683) was an ally of the English settlers, particularly the Pilgrims of Massachusetts, against his Indian rivals, esp. the powerful Narragansett tribe. He and the Mohegans fought on the English side in Indian wars including King Philip's War of 1675-6. (See Captivity of Mary Rowlandson)

Several passages concerning the historic Uncas appear in Of Plymouth Plantation, Governor William Bradford's chronicle of the Pilgrims' voyages from England to Holland to settlement in Massachusetts.

from 1637:

That I may make an end of this matter: this Secaucus (the Pequots' chief sachem [war leader]) being fled to the Mohawks, they cut off his head, with some other of the chief of them, whether to satisfy the English, or rather the Narragansetts, (who, as I have since heard, hired them to do it,) or for their own advantage, I well know not; but thus this war [the Pequot War of 1637] took end.

The rest of the Pequots were wholly driven from their place, and some of them submitted themselves to the Narragansetts, and lived under them; others of them betook themselves to the Mohegans, under Uncas, their sachem [chief], with the approbation [approval] of the English of Connecticut, under whose protection Uncas lived, and he and his men had been faithful to them in this war, and done them very good service.

But this did so vex the Narragansetts, that they had not the whole sway over them, as they have never ceased plotting and contriving how to bring them under, and because they cannot attain their ends, because of the English who have protected them, they have sought to raise a general conspiracy against the English, as will appear in an other place.

from 1643:

[T]he Narragansetts, after the subduing of the Pequots, thought to have ruled over all the Indeans about them; but the English, especially those of Connecticut holding correspondence [communication] and friendship with Uncas, sachem [chief] of the Mohegan Indians which lived near them, . . . and he had been faithful to them in the Pequot war, they were engaged to support him in his just liberties, and were contented that such of the surviving Pequots as had submited to him should remain with him and quietly under his protection.

This did much increase his [Uncas's] power and augment his greatness, which the Narragansetts could not endure to see. But Miantonomo, their chief sachem, (an ambitious and politic man,) sought privately and by treachery (according to the Indian manner) to make him away, by hiring some to kill him. Sometimes they assayed [attempted] to poison him; that not taking, then in the night time to knock him on the head in his house, or secretly to shoot him, and such like attempts. But none of these taking effect, he [Uncas] made open war upon him [Miantonomo] (though it was against the covenants [treaties] both between the English and them [the two Indian tribes], as also between themselves [the Indians], and a plain breach of the same).

He [Uncas] came suddenly upon him [Miantanomo] with 900 or 1000 men (never denouncing [threatening] any war before). The others' [Narragansetts'] power at that presents [time] was not above half so many; but it pleased God to give Uncas the victory, and he slew many of his [Miantanomo's] men, and wounded many more; but the chief of all was, he [Uncas] took Miantinomo prisoner. And seeing he [Miantanomo] was a great man, and the Narragansetts a potent people and would seek revenge, he would do nothing in the case without the advice of the English; so he (by the help and direction of those of Connecticut) kept him prisoner till this meeting of the comissioners.

The comissioners weighed the cause and passages, as they were clearly represented and sufficiently evidenced betwixt Uncas and Miantonomo; and the things being duly considered, the comissioners apparently saw that Uncas could not be safe while Miantanomo lived, but, either by secret treachery or open force, his life would still be in danger. Wherefore they thought he might justly put such a false and bloodthirsty enemy to death; but in his own jurisdiction, not in the English plantations. And they advised, in the manner of his death all mercy and moderation should be showed, contrary to the practice of the Indians, who exercise tortures and cruelty. And, Uncas having hitherto showed himself a friend to the English, and in this craving their advice, if the Narragansett Indians or others shall unjustly assault Uncas for this execution, upon notice and request, the English promise to assist and protect him as far as they may against such violence.

This was the issue of this business. The reasons and passages hereof are more at large to be seen in the acts and records of this meeting of the comissioners. And Uncas followed this advice, and accordingly executed him, in a very fair manner, acording as they advised, with due respect to his honor and greatness.

later illustration: "Uncas and Miantanomo"