|

Craig White's authors |

|

Le Ly Hayslip (1949- ) |

|

|

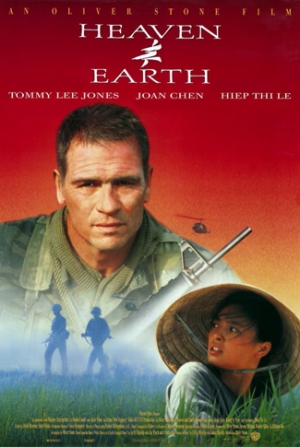

Le Ly Hayslip, born in a village near the city of Danang near the border of North and South Vietnam in 1949, is author of two memoirs about growing up during the French-Vietnamese War (1946-1954) and the American-Vietnamese War (1955-1975), after which she moved with her older American husband to the United States,and developed careers as a businesswoman and a philanthropist devoted to healing relationships between the Vietnamese and American nations and peoples. Ms. Hayslip's first memoir, When Heaven and Earth Changed Places (Doubleday, 1989), became the basis for Academy Award-winning director Oliver Stone's 1993 film Heaven and Earth, which after Platoon (1986) and Born on the Fourth of July (1989) completed Stone's trilogy of Vietnam War films. (Stone is also known for directing Wall Street [1987], The Doors [1991], JFK [1991], and the forthcoming 2016 film Snowden.) |

|

|

The selections by Hayslip in Immigrant Voices,

vol. 2

The twenty-year-old Le Ly's visit to th

In a return to Vietnam, Le Ly observes the bargaining or "haggling" at a local market: "Most unusual to me is the quarrelsome way in which they bargain . . . "Still, the longer I watch, the more I sense another force at work—something I had forgotten about in the supermarkets of America: the power of community. In the United States, I had learned to bargain only for luxuries—a car or a house. Here, people bargain from one meal to the next—consumer and producer looking each other in the eye and taking nothing for granted. The contract they arrive at—the "price" of a mango or a fig—is really an affirmation of their need for one another; a pledge of trust in the midst of suspicion; a lesson in how to survive as a community when that sense of community itself has been shattered." —When Heaven and Earth Changed Places, 209. |

|

Our

|

Immigrant Voices' selections from Child of War, Woman of Peace conclude with a powerful vision in which Le Ly finds herself alone in a national park whose lake smokes like Buddhist visions of hell. When an antlered deer stag appears, Le Ly mixes Buddhist and American references to interpret the deer as a symbol of courage amid suffering. She resolves that she can want what her new homeland offers: "I was starving and ready for anything from the great American banquet." Such a blend of myths often appears in Asian American literature, for instance Amy Tan's The Joy Luck Club (1989) and Maxine Hong Kingston's Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book (1989). Ending at this moment of resolution, our excerpts in Immigrant Voices give the impression that Le Ly's story will follow the typical contours of the American immigrant story of shock followed by acceptance and assimilation. |

|

|

In the larger context of her two book-length memoirs, this impression of Le Ly's experience as a standard immigrant narrative is misleading. In subsequent chapters, Le Ly decides not to continue in the United States but return to Vietnam to come to terms with her family and other unfinished business. The Paris Peace Talks between the United States and North Vietnam in the early 1970s appear to promise a peaceful resolution to the long war, and Le Ly's husband Ed, unsatisfied by his work status stateside, relocates himself, Le Ly, and sons Jimmy and Tommy to the North-South border area of Vietnam, near Le Ly's earlier bases in her village and Danang. Back again in Vietnam, Le Ly finds herself re-embroiled in the family and village conflicts that the Vietnamese Wars exacerbate and complicate. During Ed's absences for work she falls in love with an Italian-American Army Major, who arranges for her family's rescue when the North Vietnamese Army over-runs the border areas and initiates the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975. These passages and the entirety of both memoirs are vivid, readable, and eventful. Every page finds the narrator-heroine struggling to act conscientiously but always in a fresh crisis of survival, whether military or financial, or finding her way in family or love relationships. In the remaining 300 pages of Child of War, Woman of Peace, Ed Munro dies of emphysema and Le Ly reluctantly marries a man from Ohio, Dennis Hayslip, who looks like trouble but rescues Le Ly's sister Lan from Vietnam at the height of the refugee crisis as the North conquered the South in 1975. Le Ly has a third son (Alan) by Dennis, but Dennis is increasingly troubled by alcohol, paranoia, and rising debt from his purchasing of firearms. |

|

After Dennis's and Le Ly's divorce and his death by accident or suicide while living in his van, Le Ly continues to have difficulties knowing which American men to trust. Her story may be an example of a "war bride"—an under-explored category in American Immigrant Literature. (See graduate student Sheila Morris's research post about her mother's experience as a war bride.)

Le Ly may also represent the "heroic, clueless first generation" of immigrant families (Obj. 2d), while her sons exemplify the divided generation who speak better English and are generally Americanized but retain Old-World allegiances to their parents, as they remain faithful and supportive of their mother despite her marital difficulties.

In other respects, however, Le Ly represents not a traditional immigrant but a "trans-national migrant"—"in the 21st century, more and more people will belong to two or more societies at the same time. This is what many researchers refer to as transnational migration. Transnational migrants work, pray, and express their political interests in several contexts rather than in a single nation-state."

At length Le Ly accepts that she will not achieve the traditional, stable marriage and family she was taught to want as a young woman in Vietnam—a family and village life she experienced only briefly in the few years of relative peace between the French-Vietnamese War and the American-Vietnamese War. Instead she makes the most of her in-between status as a Vietnamese woman whom fate propelled to the United States, and she devotes herself to doing what she can to repair relations between her two nations and peoples. As her memoir ends, she establishes a non-profit non-governmental organization, the East Meets West Foundation, which cooperates with Vietnameses Veterans organizations to build health clinics in Le Ly's native village and elsewhere.

|

|

|

|

|

|

When Heaven and Earth Changed Places

The plainspoken but evocative description of challenges under stress reminded me of two early American classics of nonfiction:

![]() Mary

Rowlandson, Narrative of

the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682)

Mary

Rowlandson, Narrative of

the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682)

![]() Frederick

Douglass, Narrative of the

Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845)

Frederick

Douglass, Narrative of the

Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845)

In all three memoirs, the author is someone possessing remarkable intelligence, resourcefulness, and resilience who, it turns out, can also write very efficiently and compellingly.

Le Ly Hayslip had only a third-grade education; Rowlandson was a minister's wife when women were expected to be able to read but not to write; and Douglass, barred by law from education, taught himself to read and write.

We probably never would have heard of any of these people except that social disruptions thrust them into crises they needed to survive and then explain to others.

In contrast, however, Hayslip's memoirs are much longer than Rowlandson's and Douglass's classics. Every page she writes is well-written and full of events and even wisdom, but because she remains mostly a private citizens, a reader eventually questions learning so much of her private travails with her family and the men in her life, compared to reading the biography of a public figure who has influenced history and about whom others talk and disagree.

Were the Viet Cong comparable to Middle Eastern terrorists?

The divisions in Le Ly's family and village are powerfully convincing that

[Mid-1970s] . . . Many came to Houston, which the federal government designated as a major resettlement site along with cities in California. Its humid climate was reminiscent of Vietnam, and ample jobs and a cheap cost of living also drew refugees here. Today, the city has the nation's largest Vietnamese population outside of the San Jose and Los Angeles area. Nearly 111,000 live in the metropolitan region, two-thirds of whom were born abroad, according to the U.S. Census. They're an integral part of Houston's culture, with Vietnamese street signs, shops and restaurants lining Bellaire Boulevard and a history of political representation at City Council.

But when they first came, in the 1970s and 1980s, nearly two-thirds of the country told pollsters that they didn't want them.

In Houston, racial tensions erupted. Vietnamese shrimpers in Seabrook and Galveston clashed with white fishermen, and a Ku Klux Klan group threatened them, sailing around the bay in menacing white robes and burning effigies. U.S. marshals were ordered to protect the Vietnamese boats, and a federal lawsuit filed on their behalf eventually chased the Klan out of state.

It was a terrifying time. To help their community, some Vietnamese investors purchased rundown complexes in south Houston as a safe space for their compatriots. The largest, Thai Xuan, still exists today near Hobby Airport. Its 1,000 Vietnamese residents have transformed it into a token of the old country, renewing traditions and existing almost entirely in Vietnamese. Women still wear nón lás, cream-colored cone-shaped hats made of straw, and sell fried egg rolls in the parking lot. . . .

. . . Such strong cultural ties mean that many Vietnamese tend to stick close to one another. They cluster in Midtown and south Houston and around sprawling Bellaire Boulevard, Census data shows. The more prosperous congregate around a sliver of Memorial or in Sugar Land.

Experts say it's partly the circumstance of their arrival. Their evacuation, so sudden and traumatic, coupled with the harsh Communist punishment endured by many left behind, forged for them a shared identity around the idea that they can never go home again. Language bonds them together, as does gratitude for the generosity they have encountered.

"I appreciate America opening its arms and taking me in," said Truong, now 64. "This is the greatest country in the world." . . .

[Side-Bar to article]

![]() Nearly 800,000 Vietnamese came to the United States as

refugees between 1974 and 2013, with one-quarter arriving in just the first

three years.

Nearly 800,000 Vietnamese came to the United States as

refugees between 1974 and 2013, with one-quarter arriving in just the first

three years.

![]() According to the United Nations high commissioner for

refugees, as many as 400,000 Vietnamese who fled by boat died at sea.

According to the United Nations high commissioner for

refugees, as many as 400,000 Vietnamese who fled by boat died at sea.

![]() Houston has the nation's largest Vietnamese population

outside of the San Jose and Los Angeles area—nearly 111,000 residents.

Houston has the nation's largest Vietnamese population

outside of the San Jose and Los Angeles area—nearly 111,000 residents.

![]() The United States is home to the largest Vietnamese

diaspora in the world, and their remittances make up about 7 percent of the

communist country's gross domestic product.

The United States is home to the largest Vietnamese

diaspora in the world, and their remittances make up about 7 percent of the

communist country's gross domestic product.

![]() Hubert Vo, a Vietnamese refugee, became the first

Vietnamese to be elected to the Texas Legislature in 2004

Hubert Vo, a Vietnamese refugee, became the first

Vietnamese to be elected to the Texas Legislature in 2004

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()