|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

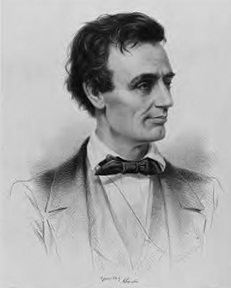

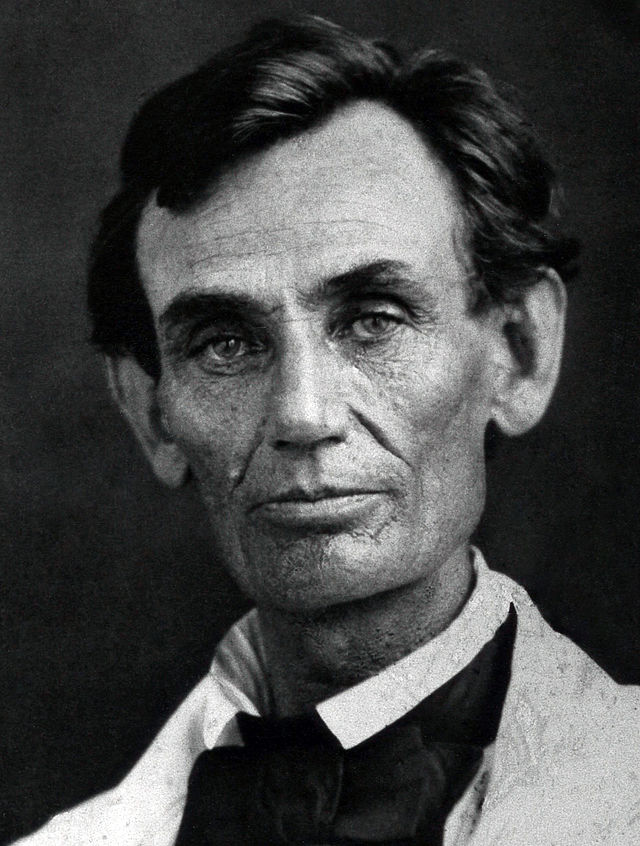

Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) The House Divided Speech 1858 (delivered on accepting the Illinois Republican nomination for U.S. Senate; Lincoln was elected U.S. President in 1860) |

|

Instructor's note: Two years before he was elected President of the

Part of the speech’s appeal was its application and extension

of a familiar biblical metaphor to a contemporary political problem: ongoing

tensions between slave and

In response,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The House Divided Speech

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention: [Republican state convention of 1858, which nominated Lincoln as its candidate for the U.S. Senare]

[1]

If we could first know where we are,

and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year since a policy

[Kansas-Nebraska Act

authored by

[2] Have we no tendency to the latter condition? [slavery spreading]

[3] Let any one who doubts, carefully contemplate that now almost complete legal combination—pieces of machinery [metaphor], so to speak—compounded of the Nebraska doctrine and the Dred Scott decision [1857 Supreme Court ruling that Constitution doesn't apply to African American slaves]. Let him consider, not only what work the machinery is adapted to do, and how well adapted, but also let him study the history of its construction, and trace, if he can, or rather fail, if he can, to trace the evidence of design, and concert of action, among its chief architects, from the beginning. [extended metaphor]

[4]

The new year of 1854 found slavery

excluded from more than half the States by State Constitutions, and from most of

the National territory by Congressional prohibition. Four days later, commenced

the struggle which ended in repealing that Congressional prohibition. This opened all the National

territory to slavery, and was the first point gained . . . .

[<Kansas-Nebraska Act]

[5] While the Nebraska Bill was passing through Congress, a law case [Dred Scott], involving the question of a negro's freedom by reason of his owner having voluntarily taken him first into a free State, and then into a territory covered by the Congressional prohibition, and held him as a slave for a long time in each, was passing through the United States Circuit Court for the District of Missouri; and both Nebraska Bill and lawsuit were brought to a decision in the same month of May, 1854. The negro's name was "Dred Scott," which name now designates the decision finally made in the case. Before the then next Presidential election [of 1856], the law case came to, and was argued in, the Supreme Court of the United States; but the decision of it was deferred until after the election. Still, before the election, Senator Trumbull, on the floor of the Senate, requested the leading advocate of the Nebraska Bill to state his opinion whether the people of a Territory can constitutionally exclude slavery from their limits; and the latter answers: "That is a question for the Supreme Court."

[6] The election came. Mr. Buchanan was elected, and the endorsement, such as it was, secured. That was the second point gained . . . . The Presidential inauguration came, and still no decision of the court; but the incoming President, in his inaugural address, fervently exhorted the people to abide by the forthcoming decision, whatever it might be. Then, in a few days, came the decision.

[7]

The reputed author of the Nebraska

Bill [Senator

Douglas,

[8]

At length a squabble springs up

between the President and the author of the Nebraska Bill

[Douglas],

on the mere question of fact, whether the Lecompton Constitution was or was not

in any just sense made by the people of Kansas; and in that quarrel the latter

[Douglas]

declares that all he wants is a fair vote for the people,

and that he cares not whether slavery be voted down or voted up. I do not

understand his declaration, that he cares not whether slavery be voted down or

voted up, to be intended by him other than as an apt definition of the policy he

would impress upon the public mind . . . . That principle is the only shred left

of his original

[9] The several points of the Dred Scott decision, in connection with Senator Douglas's "care not" policy, constitute the piece of machinery, in its present state of advancement. This was the third point gained. The working points of that machinery are:

[10]

Firstly, That no negro slave imported as such from Africa, and

descendant of such slave, can ever be a citizen of any State, in the sense of

that term as used in the Constitution of the

[11]

Secondly, That, "subject to the

Constitution of the

[12] Thirdly, That whether the holding a negro in actual slavery in a free State makes him free, as against the holder, the United States courts will not decide, but will leave to be decided by the courts of any slave state the negro may be forced into by the master. This point is made, not to be pressed immediately; but, if acquiesced in for a while, and apparently endorsed by the people at an election, then to sustain the logical conclusion that what Dred Scott's master might lawfully do with Dred Scott, in the free State of Illinois, every other master may lawfully do with any other one, or one thousand slaves, in Illinois, or in any other free State.

[13]

Auxiliary to all this, and working hand in hand with it, the Nebraska

doctrine, or what is left of it, is to educate and mould public opinion, at

least Northern public opinion, not to care whether slavery is voted down or

voted up. This shows exactly where we now are; and partially, also, whither we

are tending . . .

[14] Why was the amendment, expressly declaring the right of the people, voted down? Plainly enough now,—the speaking out then would have damaged the "perfectly free" argument upon which the election was to be carried. Why the outgoing President's felicitation on [speech in favor of] the endorsement? Why the delay of a re-argument? Why the incoming President's advance exhortation in favor of the decision? These things look like the cautious patting and petting of a spirited horse preparatory to mounting him, when it is dreaded that he may give the rider a fall. [<metaphor] And why the hasty after-endorsement of the decision by the President and others?

[15] We cannot absolutely know that all these exact adaptations are the result of preconcert [collusion, design, plan, conspiracy]. But when we see a lot of framed timbers, different portions of which we know have been gotten out at different times and places and by different workmen,—Stephen, Franklin, Roger, and James, for instance,—and when we see these timbers joined together, and see they exactly make the frame of a house or a mill [<variations and extensions of "house" metaphor>], all the tenons and mortises exactly fitting, and all the lengths and proportions of the different pieces exactly adapted to their respective places, and not a piece too many or too few,—not omitting even scaffolding,—or, if a single piece be lacking, we see the place in the frame exactly fitted and prepared yet to bring such piece in,—in such a case, we find it impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin and Roger and James all understood one another from the beginning, and all worked upon a common plan or draft drawn up before the first blow was struck . . . .

Source: Roy P. Basler, ed., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 2 (1953), 461-68.

Lincoln in 1858, year of "House Divided" speech