|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

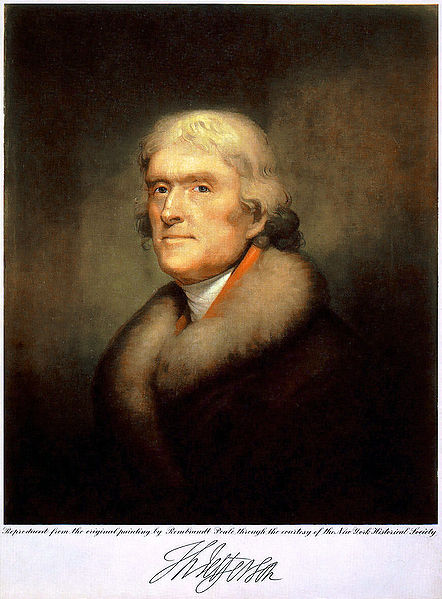

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) on American Indians from Notes on the State of Virginia (1787) (Query 6: Productions mineral, vegetable and animal; Query 11: Aborigines) |

|

from Query 6: Productions mineral, vegetable and animal

[para. 1a] The Indian of North America . . . , I can speak of him somewhat from my own knowledge, but more from the information of others better acquainted with him, and on whose truth and judgment I can rely. From these sources I am able to say, in contradiction to this representation [by a French naturalist who claimed that American creatures were weaker than those of the Old World], that he is neither more defective in ardor, nor more impotent with his female, than the white reduced to the same diet and exercise: that he is brave, when an enterprize depends on bravery; education with him making the point of honor consist in the destruction of an enemy by stratagem, and in the preservation of his own person free from injury; or perhaps this is nature; while it is education which teaches us to honor force more than finesse: that he will defend himself against an host of enemies, always choosing to be killed, rather than to surrender, though it be to the whites, who he knows will treat him well: that in other situations also he meets death with more deliberation, and endures tortures with a firmness unknown almost to religious enthusiasm with us: that he is affectionate to his children, careful of them, and indulgent in the extreme: that his affections comprehend his other connections, weakening, as with us, from circle to circle, as they recede from the center: that his friendships are strong and faithful to the uttermost extremity [*see Jefferson's note at paragraph end]: that his sensibility is keen, even the warriors weeping most bitterly on the loss of their children, though in general they endeavour to appear superior to human events: that his vivacity and activity of mind is equal to ours in the same situation; hence his eagerness for hunting, and for games of chance. [*Jefferson's note: A remarkable instance of this appeared in the case of the late Col. Byrd (Wm. Byrd II, 1674-1744), who was sent to the Cherokee nation to transact some business with them. It happened that some of our disorderly people had just killed one or two of that nation. It was therefore proposed in the council of the Cherokees that Col. Byrd should be put to death, in revenge for the loss of their countrymen. Among them was a chief called Siḷuee, who, on some former occasion, had contracted an acquaintance and friendship with Col. Byrd. He came to him every night in his tent, and told him not to be afraid, they should not kill him. After many days deliberation, however, the determination was, contrary to Siḷuee's expectation, that Byrd should be put to death, and some warriors were dispatched as executioners. Siḷuee attended them, and when they entered the tent, he threw himself between them and Byrd, and said to the warriors, `this man is my friend: before you get at him, you must kill me.' On which they returned, and the council respected the principle so much as to recede from their determination.]

[1b] The women are submitted to unjust drudgery. This I believe is the case with every barbarous people. With such, force is law. The stronger sex therefore imposes on the weaker. It is civilization alone which replaces women in the enjoyment of their natural equality. That first teaches us to subdue the selfish passions, and to respect those rights in others which we value in ourselves. Were we in equal barbarism, our females would be equal drudges. The man with them is less strong than with us, but their woman stronger than ours; and both for the same obvious reason; because our man and their woman is habituated to labour, and formed by it. With both races the sex which is indulged with ease is least athletic. An Indian man is small in the hand and wrist for the same reason for which a sailor is large and strong in the arms and shoulders, and a porter in the legs and thighs. --

[1c] They raise fewer children than we do. The causes of this are to be found, not in a difference of nature, but of circumstance. The women very frequently attending the men in their parties of war and of hunting, child-bearing becomes extremely inconvenient to them. It is said, therefore, that they have learnt the practice of procuring abortion by the use of some vegetable; and that it even extends to prevent conception for a considerable time after. During these parties they are exposed to numerous hazards, to excessive exertions, to the greatest extremities of hunger. Even at their homes the nation depends for food, through a certain part of every year, on the gleanings of the forest: that is, they experience a famine once in every year. With all animals, if the female be badly fed, or not fed at all, her young perish: and if both male and female be reduced to like want, generation becomes less active, less productive. To the obstacles then of want and hazard, which nature has opposed to the multiplication of wild animals, for the purpose of restraining their numbers within certain bounds, those of labour and of voluntary abortion are added with the Indian. No wonder then if they multiply less than we do. Where food is regularly supplied, a single farm will shew more of cattle, than a whole country of forests can of buffaloes. The same Indian women, when married to white traders, who feed them and their children plentifully and regularly, who exempt them from excessive drudgery, who keep them stationary and unexposed to accident, produce and raise as many children as the white women. Instances are known, under these circumstances, of their rearing a dozen children. An inhuman practice once prevailed in this country of making slaves of the Indians. It is a fact well known with us, that the Indian women so enslaved produced and raised as numerous families as either the whites or blacks among whom they lived. --

[1d] It has been said, that Indians have less hair than the whites, except on the head. But this is a fact of which fair proof can scarcely be had. With them it is disgraceful to be hairy on the body. They say it likens them to hogs. They therefore pluck the hair as fast as it appears. But the traders who marry their women, and prevail on them to discontinue this practice, say, that nature is the same with them as with the whites. . . .

[1e]

The principles of their society forbidding all compulsion, they are

to be led to duty and to enterprize by personal influence and persuasion. Hence

eloquence in council, bravery and address in war, become the foundations of all

consequence with them. To these acquirements all their faculties are directed.

Of their bravery and address in war we have multiplied proofs, because we have

been the subjects on which they were exercised.

[2a] Of their eminence in oratory we have fewer examples, because it is displayed chiefly in their own councils. Some, however, we have of very superior lustre [brilliance, glory]. I may challenge the whole orations of Demosthenes and Cicero [classical Roman orators], and of any more eminent orator, if Europe has furnished more eminent, to produce a single passage, superior to the speech of Logan, a Mingo chief, to Lord Dunmore, when governor of this state. And, as a testimony of their talents in this line, I beg leave to introduce it, first stating the incidents necessary for understanding it.

[2b] In the spring of the year 1774, a robbery and murder were committed on an inhabitant of the frontiers of Virginia, by two Indians of the Shawanee tribe. The neighbouring whites, according to their custom, undertook to punish this outrage in a summary [rapid, thoughtless] way. Col. Cresap, a man infamous for the many murders he had committed on those much-injured people, collected a party, and proceeded down the Kanhaway in quest of vengeance. Unfortunately a canoe of women and children, with one man only, was seen coming from the opposite shore, unarmed, and unsuspecting an hostile attack from the whites. Cresap and his party concealed themselves on the bank of the river, and the moment the canoe reached the shore, singled out their objects, and, at one fire, killed every person in it.

[2c] This happened to be the family of Logan, who had long been distinguished as a friend of the whites. This unworthy return provoked his vengeance. He accordingly signalized [distinguished] himself in the war which ensued. In the autumn of the same year, a decisive battle was fought at the mouth of the Great Kanhaway, between the collected forces of the Shawanees, Mingoes, and Delawares, and a detachment of the Virginia militia. The Indians were defeated, and sued for peace. Logan however disdained to be seen among the suppliants. But, lest the sincerity of a treaty should be distrusted, from which so distinguished a chief absented himself, he sent by a messenger the following speech to be delivered to Lord Dunmore.

|

[[2d] Logan's message to the Whites `I appeal to any white man to say, if ever he entered Logan's cabin hungry, and he gave him not meat; if ever he came cold and naked, and he clothed him not. During the course of the last [previous] long and bloody war, Logan remained idle in his cabin, an advocate for peace. Such was my love for the whites, that my countrymen pointed as they passed, and said, `Logan is the friend of white men.' I had even thought to have lived with you, but for the injuries of one man. Col. Cresap, the last spring, in cold blood, and unprovoked, murdered all the relations of Logan, not sparing even my women and children. There runs not a drop of my blood in the veins of any living creature. This called on me for revenge. I have sought it: I have killed many: I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace. But do not harbour a thought that mine is the joy of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will not turn on his heel to save his life. Who is there to mourn for Logan? -- Not one.' |

Statue in Logan, WV, of

|

[3] Before we condemn the Indians of this continent as wanting genius, we must consider that letters have not yet been introduced among them. Were we to compare them in their present state with the Europeans North of the Alps, when the Roman arms and arts first crossed those mountains, the comparison would be unequal, because, at that time, those parts of Europe were swarming with numbers [of people]; because numbers [i.e., increased population] produce emulation [or competition], and multiply the chances of improvement, and one improvement begets another. Yet I may safely ask, How many good poets, how many able mathematicians, how many great inventors in arts or sciences, had Europe North of the Alps then produced? And it was sixteen centuries after this before a Newton could be formed. I do not mean to deny, that there are varieties in the race of man, distinguished by their powers both of body and mind. . . .

[4] . . . `America has not yet produced one good poet.' When we shall have existed as a people as long as the Greeks did before they produced a Homer, the Romans a Virgil, the French a Racine and Voltaire, the English a Shakespeare and Milton, should this reproach be still true, we will enquire from what unfriendly causes it has proceeded, that the other countries of Europe and quarters of the earth shall not have inscribed any name in the roll of poets. But neither has America produced `one able mathematician, one man of genius in a single art or a single science.' In war we have produced a Washington, whose memory will be adored while liberty shall have votaries, whose name will triumph over time, and will in future ages assume its just station among the most celebrated worthies of the world, when that wretched philosophy shall be forgotten which would have arranged him among the degeneracies of nature. In physics we have produced a Franklin, than whom no one of the present age has made more important discoveries, nor has enriched philosophy with more, or more ingenious solutions of the phaenomena of nature. We have supposed Mr. Rittenhouse [David Rittenhouse, 1732-96, American astronomer] second to no astronomer living . . . . As in philosophy and war, so in government, in oratory, in painting, in the plastic art, we might show that America, though but a child of yesterday, has already given hopeful proofs of genius, as well of the nobler kinds, which arouse the best feelings of man, which call him into action, which substantiate his freedom, and conduct him to happiness, as of the subordinate, which serve to amuse him only. We therefore suppose, that this reproach is as unjust as it is unkind; and that, of the geniuses which adorn the present age, America contributes its full share. For comparing it with those countries, where genius is most cultivated, where are the most excellent models for art, and scaffoldings for the attainment of science, as France and England for instance, we calculate thus. The United States contain three millions of inhabitants; France twenty millions; and the British islands ten. We produce a Washington, a Franklin, a Rittenhouse. France then should have half a dozen in each of these lines, and Great-Britain half that number, equally eminent. It may be true, that France has: we are but just becoming acquainted with her, and our acquaintance so far gives us high ideas of the genius of her inhabitants. . . . The present war having so long cut off all communication with Great-Britain, we are not able to make a fair estimate of the state of science in that country. The spirit in which she wages war is the only sample before our eyes, and that does not seem the legitimate offspring either of science or of civilization. The sun of her glory is fast descending to the horizon. Her philosophy has crossed the Channel, her freedom the Atlantic, and herself seems passing to that awful dissolution, whose issue is not given human foresight to scan.

![]()

James River, Virginia, referenced in para.

below

(Chesapeake Bay at upper right;

North Carolina to South)

from Query 11: Aborigines

[5]

When the first effectual settlement of our colony was made, which was in 1607,

the country from the sea-coast to the mountains, and from Patowmac to the most

southern waters of James river, was occupied by upwards of forty

different tribes of Indians. Of these the

Powhatans

[Pocahontas's people], the Mannahoacs, and

Monacans, were the most powerful. Those between the sea-coast and falls of

the rivers, were in amity with one another, and attached to the

Powhatans as their link of union. Those

between the falls of the rivers and the mountains, were divided into two

confederacies; the tribes inhabiting the head waters of Patowmac and

Rappahanoc being attached to the Mannahoacs; and those on the upper parts

of James river to the Monacans. But the

Monacans and their friends were in amity with the

Mannahoacs and their friends, and waged joint

and perpetual war against the Powhatans.

We are told that the Powhatans,

Mannahoacs, and

Monacans, spoke languages so radically different, that

interpreters were necessary when they transacted business. Hence we may

conjecture, that this was not the case between all the tribes, and probably that

each spoke the language of the nation to which it was attached; which

we know to have been the case in many particular instances. Very

possibly there may have been anciently three different stocks, each of which

multiplying in a long course of time, had separated into so many little

societies. This practice results from the circumstance of their having never

submitted themselves to any laws, any coercive power, any shadow of government.

Their only controls are their manners, and that moral sense of right and wrong,

which, like the sense of tasting and feeling, in every man makes a part of his

nature. An offence against these is punished by contempt, by exclusion from

society, or, where the case is serious, as that of murder, by the individuals

whom it concerns. Imperfect as this species of coercion may seem,

crimes are very rare among them: insomuch that were it

made a question, whether no law, as among the savage Americans, or too much law,

as among the civilized Europeans, submits man to the greatest evil, one who has

seen both conditions of existence would pronounce it to be the last

[Jefferson as limited-government conservative or

libertarian]: and that the sheep are happier of themselves, than

under care of the wolves. It will be said, that great

[large] societies cannot exist without

government. The Savages therefore break them into small ones.

[6]

The

territories of the Powhatan confederacy, south of the Patowmac,

comprehended about 8000 square miles, 30 tribes, and 2400 warriors.

Capt.

[John] Smith tells us, that within 60

miles of James town were 5000 people, of whom 1500 were warriors. From this we

find the proportion of their warriors to their whole inhabitants, was as 3 to

10. The Powhatan confederacy then would consist of about 8000

inhabitants, which was one for every square mile; being about the

twentieth part of our present population in the same territory, and the

hundredth of that of the British islands.

[low population density of premodern subsistence

societies]

[7] Besides these, were the Nottoways, living on Nottoway river, the Meherrins and Tuteloes on Meherrin river, who were connected with the Indians of Carolina, probably with the Chowanocs.

. . . What would be the melancholy sequel of their [the Indians'] history, may however be augured from the census of 1669; by which we discover that the tribes therein enumerated were, in the space of 62 years, reduced to about one-third of their former numbers. Spirituous liquors, the small-pox, war, and an abridgment of territory, to a people who lived principally on the spontaneous productions of nature, had committed terrible havoc [devastation] among them, which generation [reproduction, fertility], under the obstacles opposed to it among them, was not likely to make good. That the lands of this country were taken from them by conquest, is not so general a truth as is supposed. I find in our historians and records, repeated proofs of purchase, which cover a considerable part of the lower country; and many more would doubtless be found on further search. The upper country we know has been acquired altogether by purchases made in the most unexceptionable form.

[8] Westward of all these tribes, beyond the mountains, and extending to the great lakes, were the Massawomecs, a most powerful confederacy, who harrassed unremittingly the Powhatans and Manahoacs. These were probably the ancestors of the tribes known at present by the name of the Six Nations.

[9] Very little can now be discovered of the subsequent history of these [the westward] tribes severally. . . . There remain of the Mattaponies three or four men only, and they have more negro than Indian blood in them. They have lost their language, have reduced themselves, by voluntary sales, to about fifty acres of land, which lie on the river of their own name, and have, from time to time, been joining the Pamunkies, from whom they are distant but 10 miles. The Pamunkies are reduced to about 10 or 12 men, tolerably pure from mixture with other colours. [<in contrast to Latin American cultures that recognize more interracial unions, early Anglo-USA culture delegates racial mixing to minorities.] The older ones among them preserve their language in a small degree, which are the last vestiges on earth, as far as we know, of the Powhatan language. [<non-written languages are always only a generation from extinction] They have about 300 acres of very fertile land, on Pamunkey river, so encompassed by water that a gate shuts in the whole. Of the Nottoways, not a male is left. A few women constitute the remains of that tribe. They are seated on Nottoway river, in Southampton county, on very fertile lands. At a very early period, certain lands were marked out and appropriated to these tribes, and were kept from encroachment by the authority of the laws. They have usually had trustees appointed, whose duty was to watch over their interests, and guard them from insult and injury.

[10] The Monacans and their friends, better known latterly by the name of Tuscaroras, were probably connected with the Massawomecs, or Five Nations [The Iroquois Confederacy] . For though we are told their languages were so different that the intervention of interpreters wasnecessary between them, yet do we also learn that the Erigas, a nation formerly inhabiting on the Ohio, were of the same original stock with the Five Nations, and that they partook also of the Tuscarora language. Their dialects might, by long separation, have become so unlike as to be unintelligible to one another. We know that in 1712, the Five Nations received the Tuscaroras into their confederacy, and made them the Sixth Nation. . . . [ ]

[11] I know of no such thing existing as an Indian monument: for would not honour with that name arrow points, stone hatchets, stone pipes, and half-shapen images. Of labour on the large scale, I think there is no remain as respectable as would be a common ditch for the draining of lands: unless indeed it be the Barrows [burial mounds], of which many are to be found all over this country. These are of different sizes, some of them constructed of earth, and some of loose stones. That they were repositories of the dead, has been obvious to all: but on what particular occasion constructed, was matter of doubt. . . .

Indian Barrows or burial mounds

|

|

|

[12] There being one of these in my neighbourhood, I wished to satisfy myself whether any, and which of these opinions were just. For this purpose determined to open and examine it thoroughly. It was situated on the low grounds of the Rivanna [tributary of James River], about two miles above its principal fork, and opposite to some hills, on which had been an Indian town. It was of a spheroidical form, of about 40 feet diameter at the base, and had been of about twelve feet altitude, though now reduced by the plough to seven and a half, having been under cultivation about a dozen years. Before this it was covered with trees of twelve inches diameter, and round the base was an excavation of five feet depth and width, from whence the earth had been taken of which the hillock was formed. I first dug superficially in several parts of it, and came to collections of human bones, at different depths, from six inches to three feet below the surface. These were lying in the utmost confusion, some vertical, some oblique, some horizontal, and directed to every point of the compass, entangled, and held together in clusters by the earth. Bones of the most distant parts were found together, as, for instance, the small bones of the foot in the hollow of a skull, many skulls would sometimes be in contact, lying on the face, on the side, on the back, top or bottom, so as, on the whole, to give the idea of bones emptied promiscuously from a bag or basket, and covered over with earth, without any attention to their order. . . . I proceeded then to make a perpendicular cut through the body of the barrow, that I might examine its internal structure. . . . The bones nearest the surface were least decayed. No holes were discovered in any of them, as if made with bullets, arrows, or other weapons. I conjectured that in this barrow might have been a thousand skeletons. Every one will readily seize the circumstances above related, which militate against the opinion, that it covered the bones only of persons fallen in battle; and against the tradition also, which would make it the common sepulchre of a town, in which the bodies were placed upright, and touching each other. Appearances certainly indicate that it has derived both origin and growth from the accustomary collection of bones, and deposition of them together . . . .

[13] But on whatever occasion they [the barrows or mounds] may have been made, they are of considerable notoriety [fame, common knowledge] among the Indians: for a party [of Indians] passing, about thirty years ago, through the part of the country where this barrow is, went through the woods directly to it, without any instructions or enquiry, and having staid about it some time, with expressions which were construed to be those of sorrow, they returned to the high road, which they had left about half a dozen miles to pay this visit, and pursued their journey. There is another barrow, much resembling this in the low grounds of the South branch of Shenandoah, where it is crossed by the road leading from the Rock-fish gap to Staunton. Both of these have, within these dozen years, been cleared of their trees and put under cultivation, are much reduced in their height, and spread in width, by the plough, and will probably disappear in time. There is another on a hill in the Blue ridge of mountains, a few miles North of Wood's gap, which is made up of small stones thrown together. This has been opened and found to contain human bones, as the others do. There are also many others in other parts of the country.

[14] Great question has arisen from whence came those aboriginal inhabitants of America? . . . the late discoveries of Captain Cook [James Cook (1728-79), British explorer of Pacific], coasting from Kamschatka [peninsula in Russian far east] to California, have proved that, if the two continents of Asia and America be separated at all, it is only by a narrow strait. So that from this side also, inhabitants may have passed into America: and the resemblance between the Indians of America and the Eastern inhabitants of Asia, would induce us to conjecture, that the former [Indians] are the descendants of the latter [Asians], or the latter of the former: excepting indeed the Eskimos . . . . A knowledge of their several languages would be the most certain evidence of their derivation which could be produced. . . . It is to be lamented then, very much to be lamented, that we have suffered so many of the Indian tribes already to extinguish, without our having previously collected and deposited in the records of literature, the general rudiments at least of the languages they spoke. . . .

![]()

![]()