|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

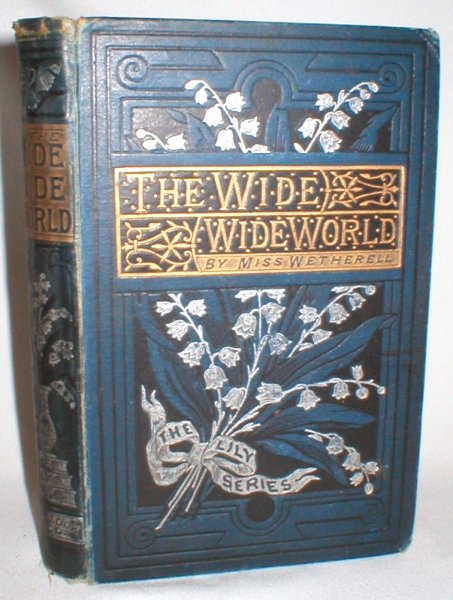

Susan B. Warner The Wide, Wide World

Chapter 17

|

|

[17.1] "Ellen

dear," said

[17.2] "Oh, no, Miss Alice, indeed we haven't; but we have got

through the worst."

[17.3] "Is the next one so bad it would spoil our supper?"

[17.4] "No," said

Ellen, "it couldn't do that, but it's bad enough though; it's

about my not going

to school. Miss Alice, I promised myself I would learn so much while mamma was

away, and surprise her when she came back, but instead of that I am not learning

anything. I don't mean not learning anything,"

said Ellen correcting herself;—"but I can't do much. When I found aunt Fortune

wasn't going to send me to school I determined I would try to study by myself;

and I have tried; but I can't get along."

[17.5] "Well now

don't lay down your knife and fork and look so doleful," said

[17.6] "Some things

I can manage well enough," said Ellen, "the easy things; but I cannot understand

my arithmetic without some one to explain it to me, and

French I can do nothing at all with, and that is what I wanted to learn

most of all

[unintentionally ironical];

and often I want to ask questions about my history."

[17.7] "Suppose," said Alice, "you go on studying by yourself as

much and as well as you can, and bring your books up to me two or three times a

week; I will hear and explain and answer questions to your heart's content,

unless you should be too hard for me. What do you say to that?"

[17.8] Ellen said nothing to it, but the color that rushed to her

cheeks,—the surprised look of delight,—were answer enough.

[17.9] "It will do

then," said

[17.10] "I don't know, ma'am; I am sorry."

[17.11] "So am I,

for your sake.

I can help you in Latin, if that would be any comfort to

you."

[17.12] "It wouldn't be much comfort to me," said Ellen, laughing;

"mamma wanted me to learn Latin, but I wanted to learn French a great deal more;

I don't care about Latin, except to please her."

[17.13] "Permit me to ask if you know English?"

[17.14] "Oh, yes, ma'am, I hope so; I knew that a great while ago."

[17.15] "Did you? I

am very happy to make your acquaintance then, for

the number of young

ladies who do know

English is in my opinion remarkably small. Are

you sure of the fact, Ellen?"

[17.16] "Why yes,

Miss

[17.17] "Will you

undertake to

write me a note of two pages

that shall not have one fault of grammar, nor one word spelt wrong, nor anything

in it that is not good English? You may

take for a subject the history of this

afternoon."

[literacy & “good English” as

class marker]

[17.18] "Yes, ma'am,

if you wish it. I hope

I can write a note

that long without making mistakes."

[17.20] "I will not stop to inquire," she

said, "whether that long

is Latin or French; but Ellen, my dear, it is not English."

[17.21] Ellen blushed a little, though she laughed too.

[17.22] "I believe I have got into the way of

saying that by hearing aunt Fortune and Mr. Van Brunt say it; I don't think I

ever did before I came here."

[local color / regional writing realistically represents local speech styles]

[17.23] "What are you so anxious to learn French for?"

[17.24] "Mamma knows it,

and I have often heard her talk French with a great many people; and papa and I

always wanted to be able to talk it too; and mamma wanted me to learn it; she

said there were a great many French books I ought to read."

[a few lines above, Mamma was for Latin]

[17.25] "That last is true, no doubt. Ellen, I will make a bargain

with you,—if you will study English with me, I will study French with you."

[17.26] "Dear Miss Alice," said Ellen, caressing her, "I'll do it

without that; I'll study anything you please."

[17.27] "Dear Ellen, I believe you would. But I should like to know

it for my own sake; we'll study it together; we shall get along nicely, I have

no doubt; we can learn to read it, at least, and that is the main point."

[17.28] "But how shall we

know what to call

[how to pronounce] the

words?" said Ellen, doubtfully.

[17.29] "That is a

grave question," said

[17.30] "Mrs. Vawse!" repeated Ellen;—"not the

grandmother of that Nancy Vawse?"

[17.31] "The very

same. Her name is not Vawse; the country people call it so, and I being one of

the country people have fallen into the way of it; but

her real name is Vosier. She was born a

Swiss, and brought up in a wealthy French family, as the personal attendant

of a young lady to whom she became exceedingly attached. This lady finally

married an American gentleman; and so great was Mrs. Vawse's love to her, that

she left country and family to follow her here. In a few years her mistress

died; she married; and since that time she has been tossed from trouble to

trouble;—a perfect sea of troubles;—till now she is left like a wreck upon this

mountain top. A fine wreck she is! I go to see her very often, and next time I

will call for you, and we will propose our French plan; nothing will please her

better, I know. By the way, Ellen,

are

you as well versed in the other common branches of education as you are in your

mother tongue?"

[17.32] "What do you mean, Miss Alice?"

[17.33] "Geography, for instance; do you know it well?"

[17.34] "Yes, ma'am; I believe so; I am sure I have studied it till I

am sick of it."

[17.35] "Can you give me

the boundaries of Great Thibet

[

[17.36] Ellen hesitated.

[17.37] "I had

rather not try," she said,—"I am not sure.

I can't remember

those queer countries in Asia and South America half so well as Europe and

[17.38] "Do you know

anything about the surface of the country in

[17.39] "Why no, ma'am," said Ellen; "nobody ever taught me that."

[17.40] "Would you like to go over the Atlas again, talking about all

these matters, as well as the mere outlines of the countries you have studied

before?"

[17.41] "Oh, yes, dearly!" exclaimed Ellen.

[17.42] "Well, I think we

may let Margery have the tea-things. But here is Captain's cake."

[in earlier chapters “the Captain” was Ellen’s father, but no big deal]

[17.43] "Oh, may I give him his supper?" said Ellen.

[17.44] "Certainly. You must carve it for him; you know I told you he

is very particular. Give him some of the egg, too—he likes that. Now where is

the Captain?"

[17.45] Not far off;

for scarcely had

[17.46] "He

generally has his supper in the outer kitchen," said

[17.47] "How handsome he is! and how large!" said Ellen.

[17.48] "Yes, he is very handsome, and more than that he is very

sensible, for a cat. Do you see how prettily his paws are marked? Jack used to

say he had white gloves on."

[17.49] "And white boots too," said Ellen. "No, only one leg is

white; pussy's boots aren't mates. Is he good-natured?"

[17.50] "Very—if you don't meddle with him."

[17.51] "I don't call that being good-natured," said Ellen laughing.

[17.52] "Nor I; but truth obliges me to say the Captain does not

permit any body to take liberties with him. He is a character, Captain Parry.

Come out on the lawn, Ellen, and we will let Margery clear away."

[17.53] "What a

pleasant face Margery has," said Ellen, as the door closed behind them; "and

what a

pleasant way she has of speaking. I like to hear her,—the words come out so

clear, and I don't know how, but not like other people."

[17.54] "You have a quick ear, Ellen; you

are very right. Margery had lived too long in

[17.55] "Then Margery is English?" said Ellen.

[17.56] "To be sure. She came over with us twelve years ago for the

pure love of my father and mother; and I believe now she looks upon John and me

as her own children. I think she could scarcely love us more if we were so in

truth. Thomas—you haven't seen Thomas yet, have you?"

[17.57] "No."

[17.58] "He is an

excellent good man in his way, and as faithful as the day is long; but he isn't

equal to his wife. Perhaps I am partial; Margery came to

[17.59] "But, Miss Alice!—"

[17.60] "What, Miss Ellen?"

[17.61] "You said

Margery came over with you?

"

[17.62] "Yes; is that what makes you look so astonished?"

[17.63] "But then you are English, too?"

[17.64] "Well, what of that? you won't love me the less, will you?"

[17.65] "Oh, no,"

said Ellen; "my

own mother came from

[17.66] "I am English born, Ellen, but you may

count me half American if

you like, for I have spent rather more than half my life here. Come this way,

Ellen, and I'll show you my garden. It is some distance off, but as near as a

spot could be found fit for it."

[17.67] They quitted the house by a little steep path leading down

the mountain, which in two or three minutes brought them to a clear bit of

ground. It was not large, but lying very prettily among the trees, with an open

view to the east and southeast. On the extreme edge and at the lower end of it

was fixed a rude bench, well sheltered by the towering forest trees. Here Alice

and Ellen sat down.

[17.68] It was near sunset; the air cool and sweet; the evening light

upon field and sky.

[17.69] "How fair it

is!" said

[17.70] "I wish they wouldn't, I am sure," said Ellen. "I am sorry

enough they are coming."

[17.71] "Why?—all seasons have their pleasures. I am not sorry at

all; I like the cold very much."

[17.72] "I guess you wouldn't, Miss Alice, if you had to wash every

morning where I do."

[17.73] "Why, where is that?"

[17.74] "Down at the spout."

[17.75] "At the

spout —what is that, pray?"

[17.76] "The spout of water, ma'am, just down a little way from the

kitchen door. The water comes in a little long, very long, trough from a spring

at the back of the pig-field, and at the end of the trough, where it pours out,

is the spout."

[17.77] "Have you no conveniences for washing in your room?"

[17.78] "Not a sign of such a thing, ma'am. I have washed at the

spout ever since I have been here," said Ellen, laughing in spite of her

vexation.

[17.79] "And do the pigs share the water with you?"

[17.80] "The pigs? Oh, no, ma'am; the trough is raised up from the

ground on little heaps of stones; they can't get at the water,—unless they drink

at the spring, and I don't think they do that, so many big stones stand around

it."

[17.81] "Well, Ellen, I must say that is rather uncomfortable, even

without any danger of four-footed society."

[17.82] "It isn't so bad just now," said Ellen, "in this warm

weather, but in that cold time we had a week or two back, do you remember, Miss

Alice?—just before the Indian summer began?—oh, how disagreeable it was! Early

in the morning, you know,—the sun scarcely up, and the cold wind blowing my hair

and my clothes all about; and then that board before the spout, that I have to

stand on, is always kept wet by the spattering of the water, and it's muddy

besides and very slippery,—there's a kind of green stuff comes upon it; and I

can't stoop down for fear of muddying myself; I have to tuck my clothes round me

and bend over as well as I can, and fetch up a little water to my face in the

hollow of my hand, and of course I have to do that a great many times before I

get enough. I can't help laughing," said Ellen, "but it isn't a laughing matter

for all that."

[17.83] "So you wash your face in your hands and have no pitcher but

a long wooden trough?—Poor child! I am sorry for you; I think you must have some

other way of managing before the snow comes."

[17.84] "The water is bitter cold already," said Ellen, "it's the

coldest water I ever saw. Mamma gave me a nice dressing-box before I came away,

but I found very soon this was a queer place for a dressing-box to come to. Why,

Miss Alice, if I take out my brush or comb I haven't any table to lay them on

but one that's too high, and my poor dressing-box has to stay on the floor. And

I haven't a sign of a bureau,—all my things are tumbling about in my trunk."

[17.85] "I think if

I were in your place I would not permit that

at any rate," said

[17.86] "Well, so they do," said Ellen,—"pretty good order; I didn't

mean 'tumbling about' exactly."

[17.87] "Always try to say what you mean

exactly."

[17.88] "But now, Ellen, love, do you know I must send you away? Do

you see the sunlight has quitted those distant hills? and it will be quite gone

soon. You must hasten home."

[17.89] Ellen made

no answer.

[17.90] "Next week,

if nothing happens, we will begin to

be busy with our books. You shall come to me Tuesday and Friday; and all the

other days you must study as hard as you can at home, for I am very particular,

I forewarn you."

[17.91] "But suppose aunt Fortune should not let me come?" said Ellen

without stirring.

[17.92] "Oh, she will. You need not speak about it; I'll come down

and ask her myself, and nobody ever refuses me anything."

[17.93] "I shouldn't think they would," said Ellen.

[17.94] "Then don't

you set the first example," said

[17.95] "Dear Miss Alice!—How can I promise that?"

[17.96] "Dear Ellen,

it is very easy. There is One who has promised to hear and answer you when you

cry to him; he will make you in his own likeness again; and to know and love him

and not be happy, is impossible. That blessed Savior!"—said

[17.97] Ellen was silent, though entering into the feeling of the

words.

[17.98] "Remember him dear Ellen;—remember your best friend. Learn

more of Christ, our dear Savior, and you can't help but be happy. Never fancy

you are helpless and friendless while you have him to go to. Whenever you feel

wearied and sorry, flee to the shadow of that great rock; will you?—and do you

understand me?"

[17.99] "Yes,

ma'am,—yes, ma'am," said Ellen, as she lifted her lips to kiss her friend.

[17.100] "Now Ellen,

dear, you must go; I

dare not keep you any longer. It will be too late now, I fear, before you reach

home."

[17.101] Quick they mounted the little path again, and soon were at

the house; and Ellen was putting on her things.

[17.102] "Next Tuesday remember,—but before that! Sunday,—you are to

spend Sunday with me; come bright and early."

[17.103] "How early?"

[17.104] "Oh, as early as you please—before breakfast—and our Sunday

morning breakfasts aren't late, Ellen; we have to set off betimes to go to

church."

[17.105] Kisses and goodbyes; and then Ellen was running down the road

at a great rate, for twilight was beginning to gather, and she had a good way to

go.

[17.106] She ran till

out of breath; then walked a while to gather breath; then ran again. Running

down hill is a pretty quick way of travelling; so before very long

she saw her aunt's house at a distance. She walked now. She had come all

the way in good spirits, though with a sense upon her mind of something

disagreeable to come; when she saw the house this disagreeable something

swallowed up all her thoughts, and she walked leisurely on, pondering what

she had to do and what she was like to meet in the doing of it.

[17.107] "If aunt

Fortune should be in a bad humor—and say something to vex me,—but I'll not be

vexed. But it will be very hard to help it;—but I

will not be vexed;—I have done wrong, and I'll tell her so, and ask

her to forgive me;—it will be hard,—but I'll do it—I'll say what I ought to say,

and then however she takes it I shall have the comfort of knowing I have done

right." "But," said conscience, "you must not say it stiffly and proudly; you

must say it humbly and as if you really felt and meant it." "I will," said

Ellen.

[17.108] She paused

in the shed and looked through the window to see what was the promise of things

within. Not good;

her aunt's step sounded

heavy and ominous; Ellen guessed she was not in a pleasant state of mind.

She opened the door,—no doubt of it,—the whole air of Miss Fortune's figure, to

the very handkerchief that was tied round her head, spoke displeasure.

[17.109] "She isn't in a good mood," said Ellen, as she went up stairs

to leave her bonnet and cape there;—"I never knew her to be good-humored when

she had that handkerchief on."

[17.110] She returned to the kitchen immediately. Her aunt was busied

in washing and wiping the dishes.

[17.111] "I have come home rather late," said Ellen pleasantly;—"shall

I help you, aunt Fortune?"

[17.112] Her aunt cast a look at her.

[17.113] "Yes, you may help me. Go and put on a pair of white gloves

and a silk apron, and then you'll be ready."

[17.114] Ellen looked down at herself. "Oh, my merino! I forgot about

that. I'll go and change it."

[17.115] Miss Fortune said nothing, and Ellen went.

[17.116] When she came back the things were all wiped, and as she was

about to put some of them away, her aunt took them out of her hands, bidding her

"go and sit down!"

[17.117] Ellen obeyed

and was mute; while

Miss Fortune dashed

round with a display of energy there seemed to be no particular call for,

and speedily had everything in its place and all straight and square about the

kitchen. When she was, as a last thing, brushing the crumbs from the floor into

the fire she broke the silence again. The old grandmother sat in the chimney

corner, but she seldom was very talkative in the presence of her stern daughter.

[17.118] "What did you come home for tonight? Why didn't you stay at

Mr. Humphreys'?"

[17.119] "Miss Alice didn't ask me."

[17.120] "That means I suppose that you would if she had?"

[17.121] "I don't know, ma'am; Miss Alice wouldn't have asked me to do

anything that wasn't right."

[17.122] "Oh, no!—of course not;—Miss Alice is a piece of perfection;

everybody says so; and I suppose you'd sing the same song who haven't seen her

three times."

[17.123] "Indeed I would," said Ellen; "I could have told that in one

seeing. I'd do anything in the world for Miss Alice."

[17.124] "Ay—I dare

say—that's the way of it.

You can show

not one bit of goodness or pleasantness to the person that does the most for you

and has all the care of you,—but the first stranger that comes along you can be

all honey to them, and make yourself out too good for common folks, and go and

tell great tales how you are used at home I suppose. I am sick of it!" said Miss

Fortune, setting up the andirons and throwing the tongs and shovel into the

corner, in a way that made the iron ring again. "One might as good be a

stepmother at once, and done with it! Come, mother, it's time for you to go to

bed."

[17.125] The old lady

rose with the meekness of habitual submission, and went up stairs with her

daughter. Ellen had time to bethink herself while they were gone, and resolved

to lose no time when her aunt came back in doing what she had to do. She would

fain have persuaded herself to put it off. "It is late," she said to herself,

"it isn't a

good time. It will be better to go to bed now, and ask aunt Fortune's pardon

tomorrow." But conscience said, "First

be reconciled to thy brother."

[17.126] Miss Fortune came down stairs presently. But before Ellen

could get any words out, her aunt prevented her.

[17.127] "Come, light your candle and be off; I want you out of the

way; I can't do anything with half a dozen people about."

[17.128] Ellen rose. "I want to say something to you first, aunt

Fortune."

[17.129] "Say it and be quick; I haven't time to stand talking."

[17.130] "Aunt Fortune," said Ellen, stumbling over her words,—"I want

to tell you that I know I was wrong this morning, and I am sorry, and I hope

you'll forgive me."

[17.131] A kind of indignant laugh escaped from Miss Fortune's lips.

[17.132] "It's easy talking; I'd rather have acting. I'd rather see

people mend their ways than stand and make speeches about them. Being sorry

don't help the matter much."

[17.133] "But I will try not to do so any more," said Ellen.

[17.134] "When I see you don't I shall begin to

think there is something in it.

Actions speak louder than words. I don't believe in this jumping into goodness

all at once."

[17.135] "Well, I will try not to, at any rate," said Ellen sighing.

[17.136] "I shall be very glad to see it. What has brought you into

this sudden fit of dutifulness and fine talking?"

[17.137] "Miss Alice told me I ought to ask your pardon for what I had

done wrong," said Ellen, scarce able to keep from crying; "and I know I did

wrong this morning, and I did wrong the other day about the letter; and I am

sorry, whether you believe it or no."

[17.138] "Miss Alice told you, did she? So all this is to please Miss

Alice. I suppose you were afraid your friend Miss Alice would hear of some of

your goings on, and thought you had better make up with me. Is that it?"

[17.139] Ellen answered, "No, ma'am," in a low tone, but had no voice

to say more.

[17.140] "I wish Miss Alice would look after her

own affairs, and let other people's houses alone. That's always the way with

your pieces of perfection;—they're eternally finding out something that isn't as

it ought to be among their neighbors.

I think people that don't set up for being quite such great things get along

quite as well in the world."

[17.141] Ellen was strongly tempted to reply, but kept her lips shut.

[17.142] "I'll tell

you what," said Miss Fortune,—"if you want me to believe that all this talk

means something

I'll tell you what you shall do,—you shall just tell Mr.

Van Brunt tomorrow about it all, and how ugly you have been these two days, and

let him know you were wrong and I was right. I believe he thinks you cannot do

anything wrong, and I should like him to know it for once."

[17.143] Ellen struggled hard with herself before she could speak;

Miss Fortune's lips began to wear a scornful smile.

[17.144] "I'll tell him!" said Ellen, at length; "I'll tell him I was

wrong, if you wish me to."

[17.145] "I

do wish it. I like people's

eyes to be opened. It'll do him good, I guess, and you too. Now, have you

anything more to say?"

[17.146] Ellen hesitated;—the color came and went;—she knew it wasn't

a good time, but how could she wait?

[17.147] "Aunt Fortune," she said, "you know I told you I behaved very

ill about that letter,—won't you forgive me?"

[17.148] "Forgive you? yes, child; I don't care anything about it."

[17.149] "Then you will be so good as to let me have my letter again?"

said Ellen, timidly.

[17.150] "Oh, I can't be bothered to look for it now; I'll see about

it some other time; take your candle and go to bed now if you've nothing more to

say."

[17.151] Ellen took

her candle and went.

Some tears were

wrung from her by hurt feeling and disappointment; but she had the smile of

conscience, and as she believed of Him whose witness conscience is. She

remembered that "great rock in a weary land," and she went to sleep in the

shadow of it.

[17.152] The next day was

Saturday. Ellen was up early, and after carefully performing her toilet duties

[morning wash, etc.], she

had a nice long hour before it was time to go downstairs. The use she made

of this hour had fitted her to do cheerfully and well her morning work; and

Ellen would have sat down to breakfast in excellent spirits if it had not been

for her promised disclosure to Mr. Van Brunt. It vexed her a little. "I told

aunt Fortune,—that was all right; but why I should be obliged to tell Mr. Van

Brunt I don't know. But if it convinces aunt Fortune that I am in earnest, and

meant what I say?—then I had better."

[17.153] Mr. Van Brunt looked uncommonly grave, she thought; her aunt,

uncommonly satisfied. Ellen had more than half a guess at the reason of both;

but make up her mind to speak, she could not, during all breakfast time. She ate

without knowing what she was eating.

[17.154] Mr. Van Brunt at length, having finished his meal without

saying a syllable, arose and was about to go forth, when Miss Fortune stopped

him. "Wait a minute, Mr. Van Brunt," she said, "Ellen has something to say to

you. Go ahead, Ellen."

[17.155] Ellen

felt, rather than saw, the

smile with which these words were spoken. She crimsoned and hesitated.

[17.156] "Ellen and I had some trouble yesterday," said Miss Fortune,

"and she wants to tell you about it."

[17.157] Mr. Van Brunt stood gravely waiting.

[17.158] Ellen raised her eyes, which were full, to his face. "Mr. Van

Brunt," she said, "aunt Fortune wants me to tell you what I told her last

night,—that I knew I behaved as I ought not to her yesterday, and the day

before, and other times."

[17.159] "And what made you do that?" said Mr. Van Brunt.

[17.160] "Tell him," said Miss Fortune, coloring, "that you were in

the wrong and I was in the right—then he'll believe it, I suppose."

[17.161] "I was wrong," said Ellen.

[17.162] "And I was right," said Miss Fortune.

[17.163] Ellen was silent. Mr. Van Brunt looked from one to the other.

[17.164] "Speak," said Miss Fortune; "tell him the whole if you mean

what you say."

[17.165] "I can't," said Ellen.

[17.166] "Why, you said you were wrong," said Miss Fortune; "that's

only half of the business; if you were wrong I was right; why don't you say so,

and not make such a shilly-shally piece of work of it?"

[17.167] "I said I was wrong," said Ellen, "and

so I was; but I never said you were right, aunt Fortune, and I don't think so."

[17.168] These words, though moderately spoken,

were enough to put Miss Fortune in a rage.

[17.169] "What did I do that was wrong?" she said; "come, I should

like to know. What was it, Ellen? Out with it; say everything you can think of;

stop and hear it, Mr. Van Brunt; come, Ellen, let's hear the whole!"

[17.170] "Thank you, ma'am, I've heerd quite enough," said that

gentleman, as he went out and closed the door.

[17.171] "And I have

said too much," said Ellen. "Pray, forgive me, aunt Fortune.

I shouldn't have

said that if you hadn't pressed me so; I forgot myself a moment. I am sorry I

said that."

[17.172] "Forgot yourself!" said Miss Fortune;

"I wish you'd forget yourself out of my house. Please to forget the place where

I am for today anyhow; I've

got enough of you for one while. You had better go to Miss Alice and get a new

lesson; and tell her you are coming on finely."

[17.173] Gladly would

Ellen indeed have gone to Miss Alice, but as the next day was Sunday she thought

it best to wait. She went sorrowfully to her own room.

"Why couldn't I be

quiet?" said Ellen. "If I had only held my tongue that unfortunate minute! what

possessed me to say that?"

[17.174] Strong passion—strong pride,—both long

unbroken; and Ellen had yet to learn that many a prayer and many a tear, much

watchfulness, much help from on high, must be hers before she could be

thoroughly dispossessed of these evil spirits. But she knew her sickness; she

had applied to the Physician;—she was in a fair way to be well.

[17.175] One thought in her solitary room that day drew streams of

tears down Ellen's cheeks. "My letter—my letter! what shall I do to get you!"

she said to herself. "It serves me right; I oughtn't to have got in a passion;

oh, I have got a lesson this time!"

![]()

![]()

—

[ ]