|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

Washington Irving (1783-1859) (author of Rip Van Winkle & The Legend of Sleepy Hollow) Washington Irving The History of New-York . . . by Diedrich Knickerbocker |

See also "Knickerbocker

Pants" |

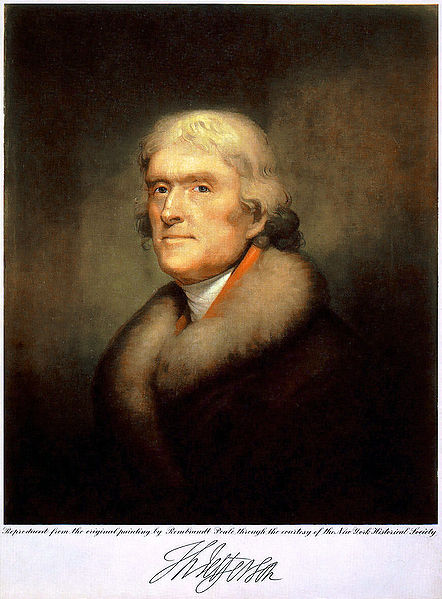

Instructor's note: Irving's History of New York, though written only 30 years after the American Revolution, is a parody of early American history that also satirizes current events of the early 1800s, particularly (in the passages below) the U.S. Presidency (1801-1809) of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826).

Jefferson was one of the younger members of the Founders' generation. Jefferson shared most of his elders' Enlightenment principles of reason, balance, and restraint, but in other regards he and Thomas Paine were more Romantic or revolutionary.

For instance, the U.S. Constitution may be a more purely Enlightenment or

Neo-Classical document than the Declaration. Its motive is not "a perfect union"

but “a more perfect union,”

Swift satirizes Jefferson as "William the Testy" or "William the irritable and self-righteous," enforcing the Enlightenment principle that the truth is found through a golden mean or balance between competing interests or ideas.

By changing Jefferson as the current U.S. President to a New-York Governor two centuries earlier, Irving follows a characteristic satirical technique of relocating its subjects to another time and place, as when L. Frank Baum in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz relocated representatives of differing political ideas to the fantasy-land of Oz, or when Jonathan Swift relocated European political arguments to various fantasy-lands in Gulliver's Travels.

This excerpt follows somewhat similar satirical portraits of previous presidents

Washington and Adams, but whereas Swift’s satire of those earlier presidents is

gentle or Horatian, his depiction of Jefferson, the sitting president, is harsh

or Juvenalian

![]()

BOOK IV.

CONTAINING THE CHRONICLES OF THE REIGN OF WILLIAM THE TESTY.

["William the Testy" = Thomas Jefferson, 2nd President, USA;

"testy" = contentious, argumentative, irritable]

[1]

When the lofty Thucydides

[Classical Greek historian; satire acknowledges Classical roots]

is about to enter upon his description of the plague that desolated Athens, one

of his modern commentators assures the reader that

the history is now going to be

exceedingly solemn, serious and pathetic

[<ripe for satire];

and hints, with that air of chuckling gratulation

[gratification]

with which a good dame

[housekeeper]

draws forth a choice morsel from a cupboard to regale a favorite, that

this plague will give his history a most

agreeable variety.

[As in comedy, problems are entertaining as long as they’re not our own. Comedy

won’t admit this, but satire does.]

[2]

In like manner did my heart leap within me when I came to the dolorous dilemma

of Fort Good Hope

[previously described],

which I at once perceived to be the forerunner of

a series of great events and

entertaining disasters.

[<mordant]

Such are the true subjects for the

historic pen. For what is history, in

fact, but a kind of Newgate Calendar

[criminal record]—a

register of the crimes and miseries that man has inflicted on his fellow-men?

[<subverts or inverts history as glorious progress]

It is a huge libel on human nature to

which we industriously add page after page, volume after volume, as if we were

building up a monument to the honor, rather than the infamy, of our species.

[3]

If we turn over the pages of these chronicles that man has written of himself,

what are the characters dignified by the

appellation of great, and held up to the admiration of posterity? Tyrants,

robbers, conquerors, renowned only for the magnitude of their misdeeds and

the stupendous wrongs and miseries they have inflicted on mankind—warriors,

who have hired themselves to the trade of blood, not from

motives of virtuous patriotism, or to protect the injured and defenseless, but

merely to gain the vaunted glory of

being adroit and successful in massacring their fellow-beings! What are the

great events that constitute a glorious

era? The fall of empires, the desolation of happy countries, splendid cities

smoking in their ruins, the proudest works of art tumbled in the dust,

the shrieks and groans of whole nations

ascending unto heaven!

[4]

It is thus the historians may be said to

thrive on the miseries of mankind, like birds of prey which hover over the

field of battle to fatten on the mighty dead. It was

observed by a great projector of inland

lock navigation, that rivers, lakes, and oceans were only formed to feed canals.

[<cf. Age of Reason extravagances like, God in his providential wisdom gave

people noses so that, when eye-glasses were invented, they’d have something to

put their glasses on]

In like manner I am tempted to believe that

plots, conspiracies, wars, victories,

and massacres are ordained by

[5]

It is a source of great delight to the

philosophers, in studying the wonderful economy of nature, to trace the mutual

dependencies of things—how they are created reciprocally for each other, and

how the most noxious and apparently unnecessary animal has its uses. Thus those

swarms of flies which are so often execrated as useless vermin are created for

the sustenance of spiders; and spiders, on the other hand, are evidently made to

devour flies. So those heroes who have

been such scourges to the world were bounteously provided as themes for the poet

and historian, while the poet and the historian were destined to record the

achievements of heroes!

[6]

These and many similar reflections naturally arose in my mind as I took up my

pen to commence the reign of William Kieft

[This “fictional” governor of New York is a caricature of Thomas Jefferson,

whose U.S. Presidency (1801-1809) overlapped with Irving’s composition and

publication of The History of New-York

];

for now the stream of our history, which hitherto has rolled in a tranquil

current, is about to depart, forever from its peaceful haunts, and brawl

[tumble]

through many a turbulent and rugged scene.

[7]

As some sleek ox, sunk in the rich repose of a clover field, dozing and chewing

the cud, will bear repeated blows before it raises

itself, so the province of Nieuw Nederlandts

[New Netherlands],

having waxed fat under the drowsy reign of the Doubter

[John Adams, 2nd U.S. President & Jefferson’s successor],

needed cuffs and kicks to rouse it into action.

The reader will now witness the manner

in which a peaceful community advances towards a state of war; which is apt to

be like the approach of a horse to a drum, with much prancing and little

progress, and too often with the wrong end foremost.

|

Detour to |

|

[8]

Wilhelmus Kieft, who in 1634 ascended the gubernatorial chair, to borrow a

favorite though clumsy appellation of modern phraseologists, was of a lofty

descent, his father being inspector of

windmills in the ancient town of Saardam

[Zaandam, town

in Northern Holland, but also alluding to the satire of Don Quixote, the courtly

knight who tilts at Windmills];

and our hero, we are told, when a boy,

made very curious investigations into the nature and operation of these

machines, which was one reason why he afterwards came to be so ingenious a

governor.

[Recognizable reference to Jefferson, who, like fellow-Founder Benjamin

[9]

His name, according to the most authentic etymologists

[students of words’ or names’ derivation],

was a corruption of Kyver; that is to

say, a wrangler or scolder; and expressed the characteristic of his family,

which for nearly two centuries had kept the windy town of Saardam in hot water,

and produced more tartars and brimstones

[Hellish fires]

than any ten families in the place; and so truly did he inherit this family

peculiarity that he had not been a year in the government of the province before

he was universally denominated

[called]

William the Testy.

His appearance answered to his name.

He was a brisk, wiry, waspish little old

gentleman, such a one as may now and then be seen stumping about our city in

a broad-skirted coat with huge buttons, a cocked hat stuck on the back of his

head, and a cane as high as his chin. His face was broad, but his features were

sharp; his cheeks were scorched into a

dusky red, by two fiery little gray eyes,

his nose turned up, and the corners of

his mouth turned down pretty much like the muzzle of an irritable pug-dog.

[diminution: change of scale typical of comedy and satire]

[10]

[>citation of scientific authorities gives rational surface to satire>]

I have heard it observed by a profound adept in human

physiology that if a woman waxes fat with the progress of years her tenure of

life is somewhat precarious, but if

haply she withers as she grows old, she lives for ever. Such promised to be the

case with William the Testy, who grew tough in proportion as he dried. He

had withered, in fact, not through the process of years, but through the

tropical fervor of his soul, which burnt like a vehement

rushlight

[hot candle]

in his bosom, inciting him to incessant

broils

[arguments]

and bickerings.

[11]

Ancient traditions speak much of his learning, and of the gallant inroads he had

made into the dead languages,

in which he had made captive a host of Greek nouns and Latin verbs, and brought

off rich booty in ancient saws

[wise sayings]

and apophthegms

[aphorisms],

which he was wont to parade in his public harangues, as a triumphant general of

yore his spolia opima

[spoils of war, or spoils of victory].

Of metaphysics he knew enough to

confound all hearers and himself into the bargain. In

logic, he knew the whole family of

syllogisms and dilemmas, and was so

proud of his skill that he never suffered even a self-evident fact to pass

unargued. It was observed, however, that he seldom got into an argument

without getting into a perplexity, and then into a passion with his adversary

for not being convinced gratis

[by grace].

[12]

He had, moreover, skirmished smartly on the frontiers of several of the

sciences, was fond of experimental philosophy, and prided himself upon

inventions of all kinds.

His abode

[in real life, Jefferson’s home was

Monticello;

another example of diminution or change of scale],

which he had fixed at a bowery, or country seat, at a short distance from the

city, just at what is now called Dutch Street,

soon abounded with proofs of his

ingenuity; patent smoke jacks

[rotisserie powered by hot air from fire]

that required a horse to work them; Dutch ovens that roasted meat without fire

[preposterous];

carts that went before the horses;

weathercocks

[weathervanes]

that turned against the wind;

and other wrong-headed contrivances that

astonished and confounded all beholders.

[13]

The house, too, was beset with paralytic

cats and dogs, the subjects of his experimental philosophy; and the yelling

and yelping of the latter

unhappy victims of science, while

aiding in the pursuit of knowledge, soon

gained for the place the name of "Dog's Misery," by which it continues to be

known even at the present day.

[contrast beautiful name of “

[14]

It is in knowledge as in swimming, he

who flounders and splashes on the surface makes more noise and attracts more

attention than the pearl diver who quietly dives in quest of treasures to the

bottom. The vast acquirements of the new governor were the theme of marvel

among the simple burghers of New Amsterdam; he figured about the place as

learned a man as a Bonze at

[15]

I have known in my time many a genius of this stamp; but, to speak my mind

freely, I never knew one who, for the ordinary purposes of life, was worth his

weight in straw. In this respect a

little sound judgment and plain common sense is worth all the sparkling genius

that ever wrote poetry or invented theories.

[contrast Enlightenment

reason against Romantic

fantasy]

Let us see how the universal acquirements of William the Testy aided him in the

affairs of government.

![]()

![]()

—

[ ] x