|

|

Online Texts for Craig White's Literature Courses

|

|

|

Selections from James Fenimore Cooper The Last of the Mohicans A Narrative of 1757 (1826)

chapters 32-33 (end) |

Statue of Tamenund in Philadelphia

|

Instructor's note: In omitted chapter 31, Uncas led the Delawares in preparations for war (yet another "epic" genre-convention, along with the frequent use of epithets instead of names).

Chapter 32

[32.1]

During the time Uncas was making this disposition of his forces, the woods were

as still, and, with the exception of those who had met in council, apparently as

much untenanted

[empty]

as when they came fresh from the hands of their Almighty

Creator. The eye could range, in every direction, through

the long and shadowed vistas of the

trees; but nowhere was any object to be seen that did not properly belong to

the peaceful and slumbering scenery.

[32.2]

Here and there a bird was heard fluttering among the

branches of the beeches, and occasionally a squirrel dropped a nut, drawing the

startled looks of the party for a moment to the place; but the instant the

casual interruption ceased, the passing air was heard murmuring above their

heads, along that verdant and undulating surface of forest, which spread itself

unbroken, unless by stream or lake, over such a vast region of country. Across

the tract of wilderness which lay between the

[32.3]

When he saw his little band collected, the scout

[Hawkeye]

threw "killdeer"

[rifle]

into the hollow of his arm, and making a silent signal that

he would be followed, he led them many rods toward the rear, into the bed of a

little brook which they had crossed in advancing. Here he halted, and after

waiting for the whole of his grave and attentive warriors to close about him, he

spoke in

[32.4]

"Do any of my young men know whither this run

[stream]

will lead us?”

[32.5]

A

[32.6]

"Before the sun could go his own length, the little water will be in the big.”

Then he added, pointing in the direction of the place he mentioned, "the two

make enough for the beavers.”

[32.7]

"I thought as much,” returned the scout, glancing his eye upward at the opening

in the tree-tops, "from the course it takes, and the bearings of the mountains.

Men, we will keep within the cover of its banks till we scent the Hurons.”

[32.8]

His companions gave the usual brief exclamation of assent, but, perceiving that

their leader was about to lead the way in person, one or two made signs that all

was not as it should be. Hawkeye, who comprehended their meaning glances, turned

and perceived that his party had been followed thus far by the singing-master.

[David Gamut, the Ichabod Crane of

Mohicans, who has faithfully served

Cora & Alice in their captivity, transforming from prissy choirmaster to resourceful woodsman]

[32.9]

"Do you know, friend,” asked the scout, gravely, and perhaps with a little of

the pride of conscious deserving in his manner, "that this is a band of rangers

chosen for the most desperate service, and put under the command of one who,

though another might say it with a better face, will not be apt to leave them

idle. It may not be five, it cannot be thirty minutes, before we tread on the

body of a Huron, living or dead.”

[32.10]

"Though not admonished of your intentions in words,”

returned David, whose face was a little flushed, and whose ordinarily quiet and

unmeaning eyes glimmered with an expression of unusual fire, "your

men have reminded me of the children of Jacob going out to battle against the

Shechemites, for wickedly aspiring to wedlock with a woman of a race that was

favored of the Lord.*

Now, I have journeyed far, and sojourned much in good and evil with the maiden

ye seek; and, though not a man of war, with my loins girded and my sword

sharpened, yet would I gladly strike a blow in her behalf.”

[32.11]

The scout hesitated, as if weighing the chances of such a strange enlistment in

his mind before he answered:

[32.12]

"You know not the use of any we'pon. You carry no rifle; and believe me, what

the Mingoes take they will freely give again.”

[32.13]

"Though not a vaunting and bloodily disposed

Goliath,” returned

David, drawing

a sling from beneath his

parti-colored and uncouth attire,

"I

have not forgotten the example of the Jewish boy.*

With this ancient instrument of war have I practiced much in my youth,

and peradventure the skill has not entirely departed from me.”

[32.14]

"Ay!” said Hawkeye, considering the deer-skin thong and apron, with a cold and

discouraging eye; "the thing might do its work among arrows, or even knives; but

these Mengwe have been furnished by the Frenchers with a good grooved barrel

[rifle]

a man. However, it seems to be your gift to go unharmed amid fire; and as you

have hitherto been favored—major, you have left your rifle at a cock; a single

shot before the time would be just twenty scalps lost to no purpose—singer, you

can follow; we may find use for you in the shoutings.”

[32.15]

"I thank you, friend,” returned

David, supplying himself, like his royal

namesake,

from among the pebbles of the brook;

"though not given to the desire to kill, had you sent me away my spirit would

have been troubled.”

[32.16]

"Remember,” added the scout, tapping his own head significantly on that spot

where Gamut was yet sore, "we come to fight, and not to musickate

[make music]. Until the

general whoop [war-cry, "charge"] is given, nothing speaks but the rifle.”

[32.17]

David nodded, as much to signify his acquiescence with the terms; and then

Hawkeye, casting another observant glance over his followers, made the signal to

proceed.

[32.18]

Their route lay, for the distance of a mile, along the bed of the water-course.

Though protected from any great danger of observation by the precipitous banks,

and the thick shrubbery which skirted the stream, no precaution known to an

Indian attack was neglected. A warrior rather crawled than walked on each flank

so as to catch occasional glimpses into the forest; and every few minutes the

band came to a halt, and listened for hostile sounds, with an acuteness of

organs that would be scarcely conceivable to a man in a less natural state.

Their march was, however, unmolested, and they reached the point where the

lesser stream was lost in the greater, without the smallest evidence that their

progress had been noted. Here the scout again halted, to consult the signs of

the forest.

[32.19]

"We are likely to have a good day for a fight,” he said, in English, addressing

Heyward, and glancing his eyes upward at the clouds, which began to move in

broad sheets across the firmament; "a bright sun and a glittering

[rifle]

barrel are no friends to true sight. Everything is favorable; they have the

wind, which will bring down their noises and their smoke, too, no little matter

in itself; whereas, with us it will be first a shot, and then a clear view. But

here is an end to our cover; the beavers have had the range of this stream for

hundreds of years, and what atween their food and their dams, there is, as you

see, many a girdled stub, but few living trees.”

[32.20]

Hawkeye had, in truth, in these few words, given no bad

description of the prospect that now lay in their front. The brook was irregular

in its width, sometimes shooting through narrow fissures in the rocks, and at

others spreading over acres of bottom land, forming little areas that might be

termed ponds. Everywhere along its bands were

the moldering relics of dead trees, in

all the stages of decay, from those that groaned on their tottering trunks

to such as had recently been robbed of those rugged coats that so mysteriously

contain their principle of life.

A few

long, low, and moss-covered piles were scattered among them, like the memorials

of a former and long-departed generation.

[gothic stylings]

[32.21]

All these minute particulars were noted by the scout, with a gravity and

interest that they probably had never before attracted. He knew that the Huron

encampment lay a short half mile up the brook; and, with the characteristic

anxiety of one who dreaded a hidden danger, he was greatly troubled at not

finding the smallest trace of the presence of his enemy. Once or twice he felt

induced to give the order for a rush, and to attempt the village by surprise;

but his experience quickly admonished him of the danger of so useless an

experiment. Then he listened intently, and with painful uncertainty, for the

sounds of hostility in the quarter where Uncas was left; but nothing was audible

except the sighing of the wind, that began to sweep over the bosom of the forest

in gusts which threatened a tempest. At length, yielding rather to his unusual

impatience than taking counsel from his knowledge, he determined to bring

matters to an issue, by unmasking his force, and proceeding cautiously, but

steadily, up the stream.

[32.22]

The scout had stood, while making his observations,

sheltered by a brake, and his companions still lay in the bed of the ravine,

through which the smaller stream debouched; but on hearing his low, though

intelligible, signal

the whole party

stole up the bank, like so many dark specters, and silently arranged

themselves around him. Pointing in the direction he wished to proceed, Hawkeye

advanced, the band breaking off in single files, and following so accurately in

his footsteps, as to leave it, if we except Heyward and David, the trail of but

a single man.

[32.23]

The party was, however, scarcely uncovered before a volley

from a dozen rifles was heard in their rear; and a

[32.24]

"Ah, I feared some deviltry like this!” exclaimed the scout, in English, adding,

with the quickness of thought, in his adopted tongue: "To cover, men, and

charge!”

[32.25]

The band dispersed at the word, and before Heyward had well recovered from his

surprise, he found himself standing alone with David. Luckily the Hurons had

already fallen back, and he was safe from their fire. But this state of things

was evidently to be of short continuance; for the scout set the example of

pressing on their retreat, by discharging his rifle, and darting from tree to

tree as his enemy slowly yielded ground.

[32.26]

It would seem that the assault had been made by a very

small party of the Hurons, which, however, continued to increase in numbers, as

it retired on its friends, until the return fire was very nearly, if not quite,

equal to that maintained by the advancing Delawares. Heyward threw himself among

the combatants, and imitating the necessary caution of his companions, he made

quick discharges with his own rifle. The contest now grew warm and stationary.

Few were injured, as both parties kept their bodies as much protected as

possible by the trees; never, indeed, exposing any part of their persons except

in the act of taking aim. But the chances were gradually growing unfavorable to

Hawkeye and his band. The quick-sighted scout perceived his danger without

knowing how to remedy it. He saw it was more dangerous to retreat than to

maintain his ground: while he found his enemy throwing out men on his flank;

which rendered the task of keeping themselves covered so very difficult to the

[32.27]

The effects of this attack were instantaneous, and to the scout and his friends

greatly relieving. It would seem that, while his own surprise had been

anticipated, and had consequently failed, the enemy, in their turn, having been

deceived in its object and in his numbers, had left too small a force to resist

the impetuous onset of the young Mohican

[Uncas with his warriors].

This fact was doubly apparent, by the rapid manner in which the battle in the

forest rolled upward toward the village, and by an instant falling off in the

number of their assailants, who rushed to assist in maintaining the front, and,

as it now proved to be, the principal point of defense.

[32.28]

Animating his followers by his voice, and his own example,

Hawkeye then gave the word to bear down upon their foes. The charge, in that

rude species of warfare, consisted merely in pushing from cover to cover, nigher

to the enemy; and in this maneuver he was instantly and successfully obeyed. The

Hurons were compelled to withdraw, and the scene of the contest rapidly changed

from the more open ground, on which it had commenced, to a spot where the

assailed found a thicket to rest upon. Here the struggle was protracted,

arduous, and seemingly of doubtful issue; the

[32.29]

In this crisis, Hawkeye found means to get behind the same tree as that which

served for a cover to Heyward; most of his own combatants being within call, a

little on his right, where they maintained rapid, though fruitless, discharges

on their sheltered enemies.

[32.30]

"You are a young man, major,” said the scout, dropping the

butt of "killdeer" to the earth, and leaning on the barrel, a little fatigued

with his previous industry; "and it may be your gift to lead armies, at some

future day, ag'in these imps, the Mingoes.

You may here see

the philosophy of an Indian fight. It consists mainly in ready hand, a quick eye

and a good cover. Now, if you had a company of the Royal Americans here, in what

manner would you set them to work in this business?”

[32.31]

"The bayonet would make a road.”

[32.32]

"Ay, there is white reason in what you say; but a man must ask himself, in this

wilderness, how many lives he can spare.

No—horse*,” continued the scout, shaking his head, like one who mused; "horse, I

am ashamed to say must sooner or later decide these scrimmages. The brutes are

better than men, and to horse must we come at last. Put a shodden hoof on the

moccasin of a red-skin, and, if his rifle be once emptied, he will never stop to

load it again.”

*[Cooper’s note:

The American forest admits of the passage of horses, there being little

underbrush, and few tangled brakes. The plan of Hawkeye is the one which has

always proved the most successful in the battles between the whites and the

Indians. . . . ]

[32.33]

"This is a subject that might better be discussed at another time,” returned

Heyward; "shall we charge?”

[32.34]

"I see no contradiction to the gifts of any man in passing his breathing spells

in useful reflections,” the scout replied. "As to rush, I little relish such a

measure; for a scalp or two must be thrown away in the attempt. And yet,” he

added, bending his head aside, to catch the sounds of the distant combat, "if we

are to be of use to Uncas, these knaves in our front must be got rid of.”

[32.35]

Then, turning with a prompt and decided air, he called

aloud to his Indians, in their own language. His words were answered by a shout;

and, at a given signal, each warrior made a swift movement around his particular

tree. The sight of so many dark bodies, glancing before their eyes at the same

instant, drew a hasty and consequently an ineffectual fire from the Hurons.

Without stopping to breathe, the

[32.36]

The combat endured only for an instant, hand to hand, and

then the assailed yielded ground rapidly, until they reached the opposite margin

of the thicket, where they clung to the cover, with the sort of obstinacy that

is so often witnessed in hunted brutes.

At this critical moment, when the success of the struggle was again becoming

doubtful, the crack of a rifle was heard behind the Hurons, and a bullet came

whizzing from among some beaver lodges, which were situated in the clearing,

in their rear, and was followed by the fierce and appalling yell of the

war-whoop.

[32.37]

"There speaks the Sagamore!"

[<Chingachgook]

shouted Hawkeye, answering the cry with his own stentorian voice; "we have them

now in face and back!”

[Re the bullet from the beaver lodges, in omitted chapters Chingachgook was

shown hiding by disguising himself as a beaver. (In another chapter Hawkeye

successfully impersonates a bear.)]

[32.38]

The effect on the Hurons was instantaneous. Discouraged by

an assault from a quarter that left them no opportunity for cover, the warriors

uttered a common yell of disappointment, and breaking off in a body, they spread

themselves across the opening, heedless of every consideration but flight. Many

fell, in making the experiment, under the bullets and the blows of the pursuing

[32.39]

We shall not pause to detail the meeting between the scout

and Chingachgook, or the more touching interview that

[32.40]

The warriors, who had breathed themselves freely in the

preceding struggle, were now posted on a bit of level ground, sprinkled with

trees in sufficient numbers to conceal them. The land fell away rather

precipitately in front, and beneath their eyes stretched, for several miles,

a narrow,

dark, and wooded vale. It was through this dense and dark forest that Uncas was

still contending with the main body of the Hurons.

[32.41]

The Mohican and his friends advanced to the brow of the hill, and listened, with

practiced ears, to the sounds of the combat. A few birds hovered over the leafy

bosom of the valley, frightened from their secluded nests; and here and there a

light vapory cloud, which seemed already blending with the atmosphere, arose

above the trees, and indicated some spot where the struggle had been fierce and

stationary.

[32.42]

"The fight is coming up the ascent

[hillside],”

said

[32.43]

"They will incline into the hollow, where the cover is thicker,” said the scout,

"and that will leave us well on their flank. Go, Sagamore

[Chingachgook];

you will hardly be in time to give the whoop, and lead on the young men.

I will fight this scrimmage with

warriors of my own color. You know me, Mohican; not a Huron of them all

shall cross the swell, into your rear, without the notice of ‘killdeer.’”

[32.44]

The Indian chief paused another moment to consider the signs of the contest,

which was now rolling rapidly up the ascent, a certain evidence that the

Delawares triumphed; nor did he actually quit the place until admonished of the

proximity of his friends, as well as enemies, by the bullets of the former,

which began to patter among the dried leaves on the ground, like the bits of

falling hail which precede the bursting of the tempest. Hawkeye and his three

companions withdrew a few paces to a shelter, and awaited the issue with

calmness that nothing but great practice could impart in such a scene.

[32.45]

It was not long before the reports of the rifles began to lose the echoes of the

woods, and to sound like weapons discharged in the open air. Then a warrior

appeared, here and there, driven to the skirts of the forest, and rallying as he

entered the clearing, as at the place where the final stand was to be made.

These were soon joined by others, until a long line of swarthy figures was to be

seen clinging to the cover with the obstinacy of desperation. Heyward began to

grow impatient, and turned his eyes anxiously in the direction of Chingachgook.

The chief was seated on a rock, with nothing visible but his calm visage,

considering the spectacle with an eye as deliberate as if he were posted there

merely to view the struggle.

[32.46]

"The time has come for the

[32.47]

"Not so, not so,” returned the scout; "when he scents his

friends, he will let them know that he is here. See, see; the knaves are getting

in that clump of pines, like bees settling after their flight. By the Lord, a

squaw might put a bullet into the center of such

a knot of

dark skins!”

[32.48]

At that instant the whoop was given, and a dozen Hurons

fell by a discharge from Chingachgook and his band. The shout that followed was

answered by a single war-cry from the forest, and a yell passed through the air

that sounded as if a thousand throats were united in a common effort. The Hurons

staggered, deserting the center of their line, and

Uncas issued from the forest through the

opening they left, at the head of a hundred warriors.

[32.49]

Waving his hands right and left, the young chief pointed out the enemy to his

followers,

who separated in pursuit. The war now divided, both wings of the broken Hurons

seeking protection in the woods again, hotly pressed by the victorious warriors

of the Lenape. A minute might have passed, but the sounds were already receding

in different directions, and gradually losing their distinctness beneath the

echoing arches of the woods.

One little

knot of Hurons, however, had disdained to seek a cover, and were retiring, like

lions at bay, slowly and sullenly up the acclivity

[hillside]

which Chingachgook and his band had just deserted, to

mingle more closely in the fray.

Magua was conspicuous in this party, both by his fierce and

savage mien, and by the air of haughty authority he yet maintained.

[32.50]

In his eagerness to expedite the pursuit,

Uncas had left himself nearly alone; but

the moment his eye caught the figure of Le Subtil

[Magua],

every other consideration was forgotten.

Raising his cry of battle, which recalled some six or seven warriors, and

reckless of the disparity of their numbers, he rushed upon his enemy. Le Renard

[Magua],

who watched the movement, paused to receive him with secret joy. But at the

moment when he thought the rashness of his impetuous young assailant had left

him at his mercy, another shout was given, and La Longue Carabine

[Hawkeye]

was seen rushing to the rescue, attended by all his white associates. The Huron

instantly turned, and commenced a rapid retreat up the ascent.

[32.51]

There was no time for greetings or congratulations; for

Uncas, though unconscious of the presence of his friends, continued the pursuit

with the velocity of the wind. In vain Hawkeye called to him to respect the

covers; the young Mohican braved the

dangerous fire of his enemies, and soon compelled them to a flight as swift as

his own headlong speed. It was fortunate that the race was of short

continuance, and that the white men were much favored by their position, or the

[32.52]

Excited by the presence of their dwellings, and tired of the chase, the Hurons

now made a stand, and fought around their council-lodge with the fury of

despair. The onset and the issue were like the passage and destruction of a

whirlwind. The tomahawk of Uncas, the blows of Hawkeye, and even the still

nervous

[active]

arm of Munro were all busy for that passing moment, and the

ground was quickly strewed with their enemies.

Still Magua, though daring and much

exposed, escaped from every effort against his life, with that sort of

fabled protection that was made to overlook the fortunes of favored heroes in

the legends of ancient poetry.

Raising a

yell that spoke volumes of anger and disappointment, the subtle chief, when he

saw his comrades fallen, darted away from the place, attended by his two only

surviving friends, leaving the

[32.53]

But Uncas, who had vainly sought him in the mêlée

[combat],

bounded forward in pursuit; Hawkeye, Heyward and David still pressing on his

footsteps. The utmost that the scout could effect, was to keep the muzzle of his

rifle a little in advance of his friend, to whom, however, it answered every

purpose of a charmed shield. Once Magua appeared disposed to make another and a

final effort to revenge his losses; but, abandoning his intention as soon as

demonstrated, he leaped into a thicket of bushes, through which he was followed

by his enemies, and

suddenly entered the

mouth of the cave already known to the reader.

[In an earlier wilderness-gothic innovation, Magua imprisoned his captives in a

cave with secret rooms and passages]

Hawkeye, who had only forborne to fire in tenderness to

Uncas, raised a shout of success, and proclaimed aloud that now they were

certain of their game. The pursuers dashed into the long and narrow entrance, in

time to catch a glimpse of the retreating forms of the Hurons. Their passage

through the natural galleries and

subterraneous apartments of the cavern was preceded by the

shrieks and cries of hundreds of

women and children. The place, seen by its

dim and uncertain light, appeared like

the shades of the infernal regions, across which unhappy ghosts and savage

demons were flitting in multitudes.

[go gothic]

[32.54]

Still Uncas kept his eye on Magua, as if life to him possessed but a single

object.

Heyward and the scout still pressed on his rear, actuated, though possibly in a

less degree, by a common feeling. But

their way was becoming intricate, in those dark and gloomy passages, and the

glimpses of the retiring warriors less distinct and frequent; and for a moment

the trace was believed to be lost,

when

a white robe was seen fluttering in the further extremity of a passage that

seemed to lead up the mountain.

[gothic dark and light]

[32.56]

"'Tis Cora!”

exclaimed Heyward, in a voice in which horror and delight were wildly mingled.

[32.57]

"Cora! Cora!” echoed Uncas,

bounding forward like a deer.

[32.58]

"'Tis the maiden!” shouted the scout. "Courage, lady; we come! we come!”

[32.59]

The chase was renewed with a diligence rendered tenfold

encouraging by this

glimpse of the

captive. But the way was rugged, broken, and in spots nearly impassable.

Uncas abandoned his rifle, and leaped forward with headlong precipitation.

Heyward rashly imitated his example, though both were, a moment afterward,

admonished of his madness by hearing the bellowing of a piece, that the Hurons

found time to discharge down the passage in the rocks, the bullet from which

even gave the young Mohican a slight wound.

[32.60]

"We must close!” said the scout, passing his friends by a desperate leap; "the

knaves will pick us all off at this distance; and see, they hold the maiden so

as the shield themselves!”

[32.61]

Though his words were unheeded, or rather unheard, his

example was followed by his companions, who, by incredible exertions, got near

enough to the fugitives to perceive that

Cora was borne along between the two warriors while Magua prescribed the

direction and manner of their flight. At this moment the forms of all four were

strongly drawn against an opening in the sky, and they disappeared. Nearly

frantic with disappointment, Uncas and Heyward increased efforts that already

seemed superhuman, and they issued from the cavern on the side of the mountain,

in time to note the route of the pursued. The course lay up the ascent, and

still continued hazardous and laborious.

[32.62]

Encumbered by his rifle, and, perhaps, not sustained by so deep an interest in

the captive as his companions, the scout suffered the latter to precede him a

little, Uncas, in his turn, taking the lead of Heyward. In this manner, rocks,

precipices and difficulties were surmounted in an incredibly short space, that

at another time, and under other circumstances, would have been deemed almost

insuperable. But the impetuous young man were rewarded by finding that,

encumbered with Cora, the Hurons were losing ground in the race.

[32.63]

"Stay, dog of the Wyandots!” exclaimed Uncas, shaking his

bright tomahawk at Magua; "a

[32.64]

"I will go no further!” cried Cora, stopping unexpectedly on a ledge of rock,

that overhung a deep precipice, at no great distance from the summit of the

mountain. "Kill me if thou wilt, detestable Huron

[Magua]; I will go no further.”

[32.65]

The supporters of the maiden raised their ready tomahawks with the impious joy

that fiends are thought to take in mischief, but Magua stayed

[stopped]

the uplifted arms. The Huron chief, after casting the

weapons he had wrested from his companions over the rock,

drew his knife, and

turned to his captive, with a look in which conflicting passions fiercely

contended.

[32.66]

"Woman,” he said, "chose; the wigwam or the knife of Le Subtil!”

[32.67]

Cora regarded him not, but dropping on her knees, she raised her eyes and

stretched her arms toward heaven, saying in a meek and yet confiding voice:

[32.68]

"I am thine; do with me as thou seest best!”

[32.69]

"Woman,” repeated Magua, hoarsely, and endeavoring in vain to catch a glance

from her serene and beaming eye, "choose!”

[32.70]

But Cora neither heard nor heeded his demand. The form of

the Huron trembled in every fibre, and he raised his arm on high, but dropped it

again with a bewildered air, like one who doubted. Once more he struggled with

himself and lifted the keen weapon again; but just then a piercing cry was heard

above them, and

Uncas appeared, leaping

frantically, from a fearful height, upon the ledge.

Magua recoiled a

step; and one of his assistants, profiting by the chance, sheathed his own knife

in the bosom of Cora.

[32.71]

The Huron

[Magua]

sprang like a tiger on his offending and already retreating

country man, but the falling form of Uncas separated the unnatural combatants.

Diverted from his object by this interruption, and

maddened by the

murder he had just witnessed, Magua buried his weapon in the back of the

prostrate

[32.72]

"Mercy! mercy! Huron,” cried Heyward, from above, in tones nearly choked by

horror; "give mercy, and thou shalt receive from it!”

[32.73]

Whirling the bloody knife up at the imploring youth, the victorious Magua

uttered a cry so fierce, so wild, and yet so joyous, that it conveyed the sounds

of savage triumph to the ears of those who fought in the valley, a thousand feet

below. He was answered by a burst from the lips of the scout, whose tall person

was just then seen moving swiftly toward him, along those dangerous crags, with

steps as bold and reckless as if he possessed the power to move in air. But when

the hunter reached the scene of the ruthless massacre, the ledge was tenanted

only by the dead.

[32.74]

His keen eye took a single look at the victims, and then

shot its glances over the difficulties of the ascent in his front.

A form stood at the brow of the

mountain, on the very edge of the giddy height, with uplifted arms, in an awful

attitude of menace. Without stopping to consider his person, the rifle of

Hawkeye was raised; but a rock, which fell on the head of one of the fugitives

below, exposed the indignant and glowing countenance of the honest

Gamut. Then

Magua issued from a crevice, and,

stepping with calm indifference over the body of the last of his associates, he

leaped a wide fissure, and

ascended the rocks at a point where the arm of David could

not reach him. A single bound would carry him to the brow of the precipice, and

assure his safety. Before taking the leap, however, the Huron paused, and

shaking his hand at the scout, he shouted:

[32.75]

"The pale faces are dogs! the

[32.76]

Laughing hoarsely, he made a desperate leap, and fell short of his mark, though

his hands grasped a shrub on the verge of the height. The form of Hawkeye had

crouched like a beast about to take its spring, and his frame trembled so

violently with eagerness that the muzzle of the half-raised rifle played like a

leaf fluttering in the wind. Without exhausting himself with fruitless efforts,

the cunning Magua suffered his body to drop to the length of his arms, and found

a fragment for his feet to rest on. Then, summoning all his powers, he renewed

the attempt, and so far succeeded as to draw his knees on the edge of the

mountain.

[32.77]

It was now, when the body of his enemy was most collected together, that the

agitated weapon of the scout was drawn to his shoulder. The surrounding rocks

themselves were not steadier than the piece became, for the single instant that

it poured out its contents. The arms of the Huron relaxed, and his body fell

back a little, while his knees still kept their position. Turning a relentless

look on his enemy, he shook a hand in grim defiance. But his hold loosened, and

his dark person was seen cutting the air with its head downward, for a fleeting

instant, until it glided past the fringe of shrubbery which clung to the

mountain, in its rapid flight to destruction.

[Cooper’s description of Magua’s fall again echoes a biblical description of Satan, Revelation 12:7-9 (English Standard Version): 7Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon. And the dragon and his angels fought back, but he was defeated, and there was no longer any place for them in heaven. And the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan,the deceiver of the whole world— he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him.]

![]()

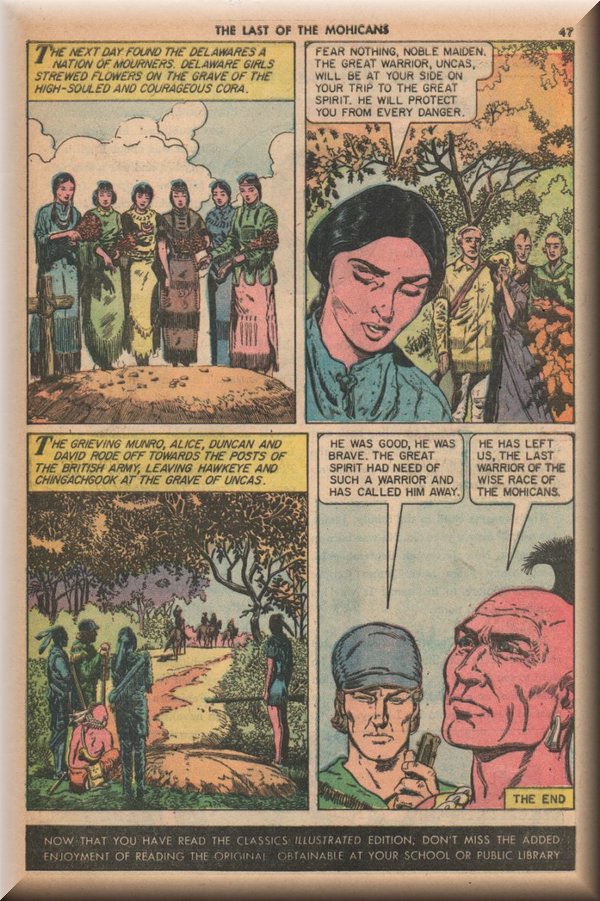

Chapter 33

[33.1]

The sun found the Lenape, on the succeeding day,

a nation of mourners. The sounds of

the battle were over, and they had fed fat their ancient grudge, and had avenged

their recent quarrel with the Mengwe

[Iroquois],

by the destruction of a whole community. The

black and murky atmosphere that

floated around the spot where the Hurons had encamped, sufficiently announced of

itself, the fate of that wandering tribe; while hundreds of

ravens, that struggled above the

summits of the mountains, or swept, in noisy flocks, across the wide ranges of

the woods, furnished a frightful direction to the scene of the combat. In short,

any eye at all practiced in the signs of a frontier warfare might easily have

traced all those unerring evidences of the ruthless results which attend an

Indian vengeance.

[33.2]

Still, the sun rose on the Lenape a nation of mourners. No shouts of success, no

songs of triumph, were heard, in rejoicings for their victory. The latest

straggler had returned from his fell employment, only to strip himself of the

terrific emblems of his bloody calling, and to join in the lamentations of his

countrymen, as a stricken people. Pride and exultation were supplanted by

humility, and the fiercest of human passions was already succeeded by the most

profound and unequivocal demonstrations of grief.

[33.3]

The lodges were deserted; but a broad belt of earnest faces

encircled a spot in their vicinity, whither everything possessing life had

repaired, and where all were now collected, in deep and awful silence. Though

beings of every rank and age, of both sexes, and of all pursuits, had united to

form this breathing wall of bodies, they were influenced by a single emotion.

Each eye was riveted on the center of

that ring, which contained the objects of so much and of so common an interest.

[33.4]

Six Delaware girls,

with their long, dark, flowing tresses falling loosely across their bosoms,

stood apart, and only gave proof of their existence as they occasionally strewed

sweet-scented herbs and forest flowers on a litter

[stretcher]

of fragrant plants that, under a pall [covering]

of Indian robes, supported

all that now remained of the ardent,

high-souled, and generous Cora. Her form was concealed in many wrappers of

the same simple manufacture, and

her

face was shut forever from the gaze of men.

[33.5]

At her

[Cora’s]

feet was seated the desolate

[Colonel]

Munro

[Cora’s & Alice’s father].

His aged head was bowed nearly to the earth, in compelled submission to the

stroke of

[33.6]

But sad and melancholy as this group may easily be

imagined, it was far less touching than another, that occupied the opposite

space of the same area.

Seated, as in

life, with his form and limbs arranged in grave and decent composure, Uncas

appeared, arrayed in the most gorgeous ornaments that the wealth of the

tribe could furnish. Rich plumes nodded above his head;

wampum

[decorative shells],

gorgets

[neckbands],

bracelets, and medals, adorned his person in profusion; though his dull eye and

vacant lineaments too strongly contradicted the idle tale of pride they would

convey.

[33.7]

Directly in front of the corpse Chingachgook was placed, without arms

[weapons],

paint, or adornment of any sort, except the bright blue blazonry of his race,

that was indelibly impressed on his naked bosom.

[<tortoise tattoo]

During

the long period that the tribe had thus been collected, the Mohican warrior had

kept a steady, anxious look on the cold and senseless countenance of his son. So

riveted and intense had been that gaze, and so changeless his attitude, that a

stranger might not have told the living from the dead, but for the occasional

gleamings of a troubled spirit, that shot athwart the dark visage of one, and

the deathlike calm that had forever settled on the lineaments of the other. The

scout was hard by, leaning in a pensive posture on his own fatal and avenging

weapon; while Tamenund, supported by the elders of his nation, occupied a high

place at hand, whence he might look down on the mute and sorrowful assemblage of

his people.

[33.8]

Just within the inner edge of the circle stood a soldier, in the military attire

of a strange nation;

and without it was his warhorse, in the center of a collection of mounted

domestics

[retainers, attendants],

seemingly in readiness to undertake some distant journey. The vestments of the

stranger announced him to be one who held a responsible situation near the

person of the captain of the Canadas

[French governor];

and who, as it would now seem, finding his errand of peace frustrated by the

fierce impetuosity of his allies, was content to become a silent and sad

spectator of the fruits of a contest that he had arrived too late to anticipate.

[The French officer was on a peace mission but arrived too late]

[33.9]

The day was drawing to the close of its first quarter, and yet had the multitude

maintained its breathing stillness since its dawn.

[33.10]

No sound louder than a stifled sob had been heard among

them, nor had even a limb been moved throughout that long and painful period,

except to perform the simple and touching offerings that were made, from time to

time, in commemoration of the dead.

The patience and

forbearance of Indian fortitude could alone support such an appearance of

abstraction, as seemed now to have turned each dark and motionless figure into

stone.

[33.11]

At length, the sage of the

[33.12]

"Men of the Lenape!” he said, in low, hollow tones, that sounded like a voice

charged with some prophetic mission: "the face of the Manitou

[Great Spirit]

is behind a cloud! His eye is turned from you; His ears are shut; His tongue

gives no answer. You see him not; yet His judgments are before you. Let your

hearts be open and your spirits tell no lie. Men of the Lenape! the face of the

Manitou is behind a cloud.”

[33.13]

As this simple and yet terrible annunciation stole on the

ears of the multitude, a stillness as deep and awful succeeded as if the

venerated spirit they worshiped had uttered the words without the aid of human

organs; and even the inanimate Uncas appeared a being of life, compared with the

humbled and submissive throng by whom he was surrounded. As the immediate

effect, however, gradually passed away, a low murmur of voices commenced a sort

of chant in honor of the dead. The

sounds were those of females, and were thrillingly soft and wailing. The

words were connected by no regular continuation, but as one ceased another took

up the eulogy, or lamentation, whichever it might be called, and gave vent to

her emotions in such language as was suggested by her feelings and the occasion.

At intervals the speaker was interrupted by general and loud bursts of sorrow,

during which the girls around the bier

[coffin]

of Cora plucked the plants and flowers blindly from her body, as if bewildered

with grief. But, in the milder moments of their plaint, these emblems of purity

and sweetness were cast back to their places, with every sign of tenderness and

regret. Though rendered less connected by many and general interruptions and

outbreakings, a translation of their language would have contained a regular

descant

[melody],

which, in substance, might have proved to possess a train of consecutive ideas.

[33.14]

A girl, selected for the task by her rank and qualifications, commenced by

modest allusions to the qualities of the deceased warrior, embellishing her

expressions with those oriental [Asian] images that the Indians have probably

brought with them from the extremes of the other continent, and which form of

themselves a link to connect the ancient histories of the two worlds. She called

him

[Uncas]

the "panther of his tribe"; and described him as one whose

moccasin left no trail on the dews; whose bound was like the leap of a young

fawn; whose eye was brighter than a star

in the dark night; and whose voice, in battle, was loud as the thunder of the

Manitou. She reminded him of the mother who bore him, and dwelt forcibly on

the happiness she must feel in possessing such a son. She bade him tell her,

when they met in the world of spirits, that the

[33.15]

Then, they who succeeded, changing their tones to a milder

and still more tender strain,

alluded,

with the delicacy and sensitiveness of women, to the stranger maiden

[Cora],

who had left the upper earth at a time so near his

[Uncas’s]

own departure, as to render the will of the Great Spirit too manifest to be

disregarded.

They admonished him

[Uncas]

to be kind to her [Cora],

and to have consideration for her ignorance of those arts which were so

necessary to the comfort of a warrior like himself. They dwelled upon her

matchless beauty, and on her noble resolution,

without the taint of envy, and as angels

may be thought to delight in a superior excellence; adding, that these

endowments should prove more than equivalent for any little imperfection in her

education.

[33.16]

After which, others again, in due succession, spoke to the

maiden herself, in the low, soft language of tenderness and love. They

exhorted her

[Cora]

to be of cheerful mind, and to fear nothing for her future welfare. A hunter

[Uncas]

would be her companion,

who knew how to provide for her smallest wants; and a warrior was at her side

who was able to protect he against every danger. They promised that her path

should be pleasant, and her burden light. They cautioned her against unavailing

regrets for the friends of her youth, and the scenes where her father had dwelt;

assuring her that

the "blessed hunting

grounds of the Lenape,” contained vales as pleasant, streams as pure; and

flowers as sweet, as the "heaven of the pale faces.”

They advised her to be attentive to the

wants of her companion, and never to forget the distinction which the Manitou

had so wisely established between them. Then, in a wild burst of their chant

they sang with united voices the temper of the Mohican's

[Uncas’s]

mind. They pronounced him noble, manly and generous; all

that became a warrior, and all that a maid might love. Clothing their ideas in

the most remote and subtle images, they betrayed, that,

in the short period of their intercourse

[interaction],

they had discovered, with the intuitive perception of their sex, the truant

disposition of his inclinations. The

[33.17]

Then, with another transition in voice and subject,

allusions were made to the virgin who

wept in the adjacent lodge. They compared her to flakes of snow; as pure, as

white, as brilliant, and as liable to melt in the fierce heats of summer, or

congeal in the frosts of winter. They doubted not that she was lovely in the

eyes of the young chief, whose skin and whose sorrow seemed so like her own; but

though far from expressing such a preference, it was evident they

deemed her less excellent than the maid

they mourned. Still they denied her no need her rare charms might properly

claim. Her ringlets were compared to the exuberant tendrils of the vine, her eye

to the blue vault of heavens, and the most spotless cloud, with its glowing

flush of the sun, was admitted to be less attractive than her bloom.

[33.18]

During these and similar songs nothing was audible but the

murmurs of the music; relieved, as it was, or rather rendered terrible, by those

occasional bursts of grief which might be called its choruses. The

[33.19]

The scout

[Hawkeye],

to whom alone, of all the white men, the words were intelligible, suffered

himself to be a little aroused from his meditative posture, and bent his face

aside, to catch their meaning, as the girls proceeded. But

when they spoke of the future prospects

of Cora and Uncas, he shook his head, like one who knew the error of their

simple creed, and resuming his reclining attitude, he maintained it until

the ceremony, if that might be called a ceremony, in which feeling was so deeply

imbued, was finished.

Happily for the self-command of both Heyward and Munro,

they knew not the meaning of the wild sounds they heard.

[33.20]

Chingachgook was a solitary exception to the interest manifested by the native

part of the audience. His look never changed throughout the whole of the scene,

nor did a muscle move in his rigid countenance, even at the wildest or the most

pathetic parts of the lamentation. The cold and senseless remains of his son was

all to him, and every other sense but that of sight seemed frozen, in order that

his eyes might take their final gaze at those lineaments he had so long loved,

and which were now about to be closed forever from his view.

[33.21]

In this stage of the obsequies

[rites],

a warrior much renowned for deed in

arms, and more especially for services in the recent combat, a man of stern and

grave demeanor, advanced slowly from the crowd, and placed himself nigh the

person of the dead.

[33.22]

"Why hast thou left us, pride of the Wapanachki?”

[or Abenaki or Wabanahki, another name for Algonquian peoples]

he said, addressing himself to the dull ears of Uncas, as if the empty clay

retained the faculties of the animated man; "thy time has been like that of the

sun when in the trees; they glory brighter than his light at noonday. Thou art

gone, youthful warrior, but a hundred Wyandots

[Hurons]

are clearing the briers from thy path to the world of the

spirits. Who that saw thee in battle

would believe that thou couldst die? Who before thee has ever shown Uttawa

[name of speaker]

the way into the fight? Thy feet were like the wings of eagles; thine arm

heavier than falling branches from the pine; and thy voice like the Manitou

[Great Spirit]

when He speaks in the clouds. The tongue of Uttawa is weak,” he added, looking

about him with a melancholy gaze, "and his heart exceeding heavy. Pride of the

Wapanachki, why hast thou left us?”

[33.23]

He was succeeded by others, in due order, until most of the high and gifted men

of the nation had sung or spoken their tribute of praise over the manes

[spirits] of the

deceased chief. When each had ended, another deep and breathing silence reigned

in all the place.

[33.24]

Then a low, deep sound was heard, like the suppressed accompaniment of distant

music, rising just high enough on the air to be audible, and yet so

indistinctly, as to leave its character, and the place whence it proceeded,

alike matters of conjecture. It was, however, succeeded by another and another

strain, each in a higher key, until they grew on the ear, first in long drawn

and often repeated interjections, and finally in words. The lips of Chingachgook

had so far parted, as to announce that it was the monody

[death-lament]

of the father. Though not an eye was turned toward him nor

the smallest sign of impatience exhibited, it was apparent, by the manner in

which the multitude elevated their heads to listen, that they drank in the

sounds with an intenseness of attention, that none but Tamenund himself had ever

before commanded. But they listened in vain. The strains rose just so loud as to

become intelligible, and then grew fainter and more trembling, until they

finally sank on the ear, as if borne away by a passing breath of wind. The lips

of the Sagamore closed, and he remained silent in his seat, looking with his

riveted eye and motionless form, like some creature that had been turned from

the Almighty hand with the form but without the spirit of a man. The

[33.25]

A

signal was given, by one of the elder chiefs, to the women who crowded that part

of the circle near which the body of Cora lay. Obedient to the sign, the girls

raised the bier to the elevation of their heads, and advanced with slow and

regulated steps, chanting, as they proceeded, another wailing song in praise of

the deceased. Gamut, who had been a close observer of rites he deemed so

heathenish, now bent his head over the shoulder of the unconscious father,

whispering:

[33.26]

"They move with the remains of thy child; shall we not follow, and see them

interred with Christian burial?”

[33.27]

Munro started, as if the last trumpet had sounded in his ear, and bestowing one

anxious and hurried glance around him, he arose and followed in the simple

train, with the mien of a soldier, but bearing the full burden of a parent's

suffering. His friends pressed around him with a sorrow that was too strong to

be termed sympathy—even the young Frenchman joining in the procession, with the

air of a man who was sensibly touched at the early and melancholy fate of one so

lovely. But when the last and humblest female of the tribe had joined in the

wild and yet ordered array, the men of the Lenape contracted their circle, and

formed again around the person of Uncas, as silent, as grave, and as motionless

as before.

[33.28]

The place which had been chosen for

the grave of Cora was a little

knoll, where a cluster of young and healthful pines had taken root,

forming of

themselves a melancholy and appropriate shade over the spot. On reaching it the

girls deposited their burden, and continued for many minutes waiting, with

characteristic patience, and native timidity, for some evidence that they whose

feelings were most concerned were content with the arrangement. At length the

scout, who alone understood their habits, said, in their own language:

[33.29]

"My daughters have done well; the white men thank them.”

[33.30]

Satisfied with this testimony in their favor, the girls

proceeded to deposit the body in a shell, ingeniously, and not inelegantly,

fabricated of the bark of the birch; after which they lowered it into its dark

and final abode.

The ceremony of

covering the remains, and concealing the marks of the fresh earth, by leaves and

other natural and customary objects, was conducted with the same simple and

silent forms. But when the labors of the kind beings who had performed these

sad and friendly offices were so far completed, they hesitated, in a way to show

that they knew not how much further they might proceed. It was in this stage of

the rites that the scout again addressed them:

[33.31]

"My young women have done enough,” he said: "the spirit of

the pale face has no need of food or raiment, their gifts being according to

the heaven of their color. I see,”

he added, glancing an eye at David, who was preparing his book in a manner that

indicated an intention to lead the way in sacred song, "that one who better

knows the Christian fashions is about to speak.”

[33.32]

The females

stood modestly aside, and, from having been the principal actors in the scene,

they now became the meek and

attentive

observers of that which followed. During the time David occupied in pouring

out the pious feelings of his spirit in this manner, not a sign of surprise, nor

a look of impatience, escaped them. They listened like those who knew the

meaning of the strange words, and appeared as if they felt the mingled emotions

of sorrow, hope, and resignation, they were intended to convey.

[33.33]

Excited by the scene he had just witnessed, and perhaps influenced by his own

secret emotions, the master of song exceeded his usual efforts. His full rich

voice was not found to suffer by a comparison with the soft tones of the girls;

and his more modulated strains possessed, at least for the ears of those to whom

they were peculiarly addressed, the additional power of intelligence. He ended

the anthem, as he had commenced it, in the midst of a grave and solemn

stillness.

[33.34]

When, however, the closing cadence had fallen on the ears

of his auditors, the secret, timorous glances of the eyes, and the general and

yet subdued movement of the assemblage, betrayed that

something was expected from the father

of the deceased. Munro seemed sensible that the time was come for him to

exert what is, perhaps, the greatest effort of which human nature is capable. He

bared his gray locks, and looked around the timid and quiet throng by which he

was encircled, with a firm and collected countenance. Then, motioning with his

hand for the scout to listen, he said:

[33.35]

"Say to these kind and gentle females, that a heart-broken

and failing man returns them his thanks. Tell them, that the Being we all

worship, under different names, will be mindful of their charity; and that the

time shall not be distant when we may assemble around His throne

without distinction of sex, or rank, or

color.”

[33.36]

The scout listened to the tremulous voice in which the

veteran delivered these words, and

shook his head

slowly when they were ended, as one who doubted their efficacy.

[33.37]

"To tell them this,” he said, "would be to tell them that the snows come not in

the winter, or that the sun shines fiercest when the trees are stripped of their

leaves.”

[33.38]

Then turning to the women, he made such a communication of the other's gratitude

as he deemed most suited to the capacities of his listeners. The head of Munro

had already sunk upon his chest, and he was again fast relapsing into

melancholy, when the young Frenchman before named ventured to touch him lightly

on the elbow. As soon as he had gained the attention of the mourning old man, he

pointed toward a group of young Indians, who approached with a light but closely

covered litter, and then pointed upward toward the sun.

[33.39]

"I understand you, sir,” returned Munro, with a voice of forced firmness; "I

understand you. It is the will of Heaven, and I submit. Cora, my child! if the

prayers of a heart-broken father could avail thee now, how blessed shouldst thou

be! Come, gentlemen,” he added, looking about him with an air of lofty

composure, though the anguish that quivered in his faded countenance was far too

powerful to be concealed, "our duty here is ended; let us depart.”

[33.40]

Heyward gladly obeyed a summons that took them from a spot

where, each instant, he felt his self-control was about to desert him. While his

companions were mounting, however, he found time to press the hand of the scout,

and to repeat the terms of an engagement they had made to meet again within the

posts of the British army. Then, gladly throwing himself into the saddle, he

spurred his charger to the side of the litter, whence law and stifled sobs alone

announced the presence of

[33.41]

But the tie which, through their common calamity, had united the feelings of

these simple dwellers in the woods [<the Indians] with the strangers

[Uncas, Cora, etc.]

who had thus transiently visited them, was not so easily

broken. Years passed away before the

traditionary tale of the white maiden, and of the young warrior of the Mohicans

ceased to beguile the long nights and tedious marches, or to animate their

youthful and brave with a desire for vengeance. Neither were the secondary

actors in these momentous incidents forgotten. Through

the medium of the scout, who served

for years afterward as

a link between

them and civilized life, they learned, in answer to their inquiries, that

the "Gray Head"

[Colonel Munro]

was speedily gathered to his fathers—borne down, as was erroneously believed, by

his military misfortunes; and that the "Open Hand"

[Duncan]

had conveyed his surviving daughter far into the settlements of the pale faces,

where her tears had at last ceased to flow, and had been succeeded by the bright

smiles which were better suited to her joyous nature.

[Sentimental-domestic rhetoric indicates that

[33.42]

But these were events of a time later than that which

concerns our tale. Deserted by all of his color, Hawkeye returned to the spot

where his sympathies led him, with a force that no ideal bond of union could

destroy. He was just in time to catch a parting look of the features of Uncas,

whom the

[33.43]

The movement, like the feeling, had been simultaneous and general. The same

grave expression of grief, the same rigid silence, and the same deference to the

principal mourner, were observed around the place of interment as have been

already described. The body was deposited in an attitude of repose, facing the

rising sun, with the implements of war and of the chase at hand, in readiness

for the final journey. An opening was left in the shell, by which it was

protected from the soil, for the spirit to communicate with its earthly

tenement, when necessary; and the whole was concealed from the instinct, and

protected from the ravages of the beasts of prey, with an ingenuity peculiar to

the natives. The manual rites then ceased and all present reverted to the more

spiritual part of the ceremonies.

[33.44]

Chingachgook

became once more the object of the common attention.

He had not yet spoken, and something

consolatory and instructive was expected from so renowned a chief on an occasion

of such interest. Conscious of the wishes of the people, the stern and

self-restrained warrior raised his face, which had latterly been buried in his

robe, and looked about him with a steady eye. His firmly compressed and

expressive lips then severed, and for the first time during the long ceremonies

his voice was distinctly audible. "Why do my brothers mourn?” he said, regarding

the dark race of dejected warriors by whom he was environed; "why do my

daughters weep? that a young man has gone to the happy hunting-grounds; that a

chief has filled his time with honor? He was good; he was dutiful; he was brave.

Who can deny it? The Manitou had need of such a warrior, and He has called him

away. As for me, the son and the father of Uncas, I am a blazed

[burnt]

pine, in a clearing of the pale faces. My race has gone

from the shores of the salt lake and the hills of the

[33.45]

"No, no,” cried Hawkeye,

who had been gazing with a yearning look at the rigid features of his friend,

with something like his own self-command, but whose philosophy could endure no

longer; "no, Sagamore, not alone.

The

gifts of our colors may be different, but God has so placed us as to journey in

the same path. I have no kin, and I may also say, like you, no people. He was

your son, and a red-skin by nature; and it may be that your blood was

nearer—but, if ever I forget the lad who has so often fou't at my side in

war, and slept at my side in peace, may He who made us all, whatever may be our

color or our gifts, forget me! The boy has left us for a time; but, Sagamore,

you are not alone.”

[33.46]

Chingachgook grasped the hand that, in the warmth of feeling, the scout had

stretched across the fresh earth, and in an attitude of friendship these two

sturdy and intrepid woodsmen bowed their heads together, while scalding tears

fell to their feet, watering the grave of Uncas like drops of falling rain.

[33.47]

In the midst of the awful stillness with which such a burst of feeling, coming

as it did, from the two most renowned warriors of that region, was received,

Tamenund lifted his voice to disperse the multitude.

[33.48]

"It is enough,” he said.

"Go, children of the Lenape, the anger

of the Manitou is not done. Why should Tamenund stay? The pale faces are masters

of the earth, and the time of the red men has not yet come again. My day has

been too long. In the morning I saw the sons of Unamis

[the great tortoise]

happy and strong; and yet, before the night has come, have I lived to see the

last warrior of the wise race of the Mohicans.”

![]()

![]()

![]()