|

American Literature: Romanticism research assignment Student Research Submissions 2015 Research Journal |

|

Heather Minette Schutmaat

12

May 2015

An Exploration of the Sublime

Introduction: Experiencing the Sublime

My

fascination with the sublime derived from recalling moments in my own life when

I experienced this curious, mystifying mixture of emotions, of both beauty and

terror, of both pleasure and pain. The first time I encountered the phenomenon,

I was twenty years old and standing on a mountaintop on La Costa Brava of Spain.

From my vantage point, I could see France standing gently to the left, and

mountains sweeping lavishly to the right. Ahead of me the brilliant blue of the

Mediterranean Sea rolled out endlessly in the light of a sinking sun, and I felt

so overwhelmed by such powerful, almost forceful, beauty that I found it

difficult to breathe. My surroundings, the mountains and sea and sky, were

literally breathtaking, and so beautiful that my heart galloped and my entire

body trembled. All at once I felt both euphoric and absolutely terrified.

Returning to my flat in Barcelona that evening, I wrote of my experience: “It

was as though, in one single moment, I felt everything. All the joy and sadness

of my entire life returned in an instant and ran throughout my whole body,” “I

felt so big, as if I could reach the sky or sing or laugh and God could hear me,

but I also felt so small and invisible in its immensity. I was both gigantic,

embracing the entire world, and the tiniest speck, floating through the

boundless sky.”

I

contemplated this moment for a long time ahead, doubting I would experience

anything like it again, until the day my son was born. There is truly no high in

the human experience like seeing your child for the first time. The feeling I

experienced when witnessing the beauty of the Mediterranean, the sight of

France, the rolling mountains along the coast, and the colors of a Spanish sky,

were multiplied infinitely the moment I saw Jude. Upon seeing his round eyes

like perfect spheres of light, the way he moved as if still in water, was the

most exhilarating moment I have experienced. I’ve often heard parents refer to

the births of their children as “pure joy,” and while it was undoubtedly the

most joyous and beautiful moment of my life, it was also the most terrifying.

I’ll never forget the way my overwhelming love for my newborn child, the kind of

love I never knew until I became a mother, manifested itself as a physical pain

in my chest, as a feeling of terror.

Whatever it was that happened within me during these moments, on the mountaintop

in Spain and on the day my son was born, was something I’ve never been able to

sufficiently explain. I’ve often written about moments of pleasure and pain in

my poetry, although on a smaller scale, such as the sight of the vast fields of

sunflowers between Pisa and Florence framed by a train window so scenic it hurt,

or the echo of church bells in Florence dancing through the streets so beautiful

and thrilling and anxiety inducing, and moments of mindfulness when I’ve studied

my child, the way he moves in a moment of play, the way the sun follows him and

lights his being, and I feel my love for him to such an extent that my body

somehow processes it as a profound sadness or fear. I’ve always been so

fascinated by these moments, yet remained focused on their ineffability, once

referring to it as “the gap between feelings and language that I cannot fill.”

While I could describe, I could never define the combination of joy and fear

that I had simultaneously experienced. That is, until I began studying

literature and discovered that there is literary term for these moments of

beauty and terror: All this time, what I have been experiencing is “the

sublime.”

With

this newfound fascination with the sublime, I became interested in discovering

the origins of the concept of the sublime, in what genre the sublime is the most

prominent, and where the sublime still thrives today in other forms of art.

The

Origin of the Sublime & The Sublime and Romantic Poetry

According to all the encyclopedias of philosophy and literature that I

used in my research, such as Bloomsbury

Guide to Human Thought, “the term Sublime (Latin, ‘what is under the

threshold [of experience]’ was first named by the literary critic Longinus.”

Encyclopedia of Philosophy states

that Longinus first theorized the sublime in his work “On

the Sublime, written in the first century CE,” and also asserts “Longinus

conceives sublimity as a quality of elevated prose of great rhetorical power.”

It wasn’t until the seventeenth century that the sublime became linked to

natural phenomena, and later with incomprehensible excesses of natural force. In

1757, philosopher Edmund Burke, in his work

A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin

of Our ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, “provided an empiricist

account of kinds of objects and situations that induce sublime perceptual

experiences. Where beauty is found for Burke in things, the perception of which

seems to harmonize with human sensory capacities, the sublime object of

perception challenges our senses or exceeds our perceptual grasp” (Encyclopedia

of Philosophy). The concept of the sublime was also taken up by philosopher

Immanuel Kant in 1790 who described the sublime, in his work

The Critique of Judgment, as a

“feeling of humanity confronted with something of limitless power” and he

defined sublime qualities “those which transcend understanding” (Bloomsbury

Guide to Human Thought).

Bloomsbury Guide to Human Thoughts

explains that the sublime “had an enormous currency among 18th-Century

European thinkers and influenced the arts, philosophy, and politics” and it also

had “a crucial effect on the rise of Romanticism in the arts” because “such

ideas were the antithesis of scientific rationalism” and “helped to create

a standoff between science and the arts which did not exist until the 18th

century, but which has, some say, been prevalent ever since.” As the

Handbook of Romanticism Studies sums

up, “in the Romantic period, between about 1760 and 1830, the sublime was an

aesthetic, philosophical, and psychological term vigorously debated in

intellectual and artistic circles, where it was used to describe the grandeur of

religious, literary, and visual experiences” (55).

Therefore, the origin of the sublime can be traced back to Longinus who

first named the sublime, and was a major subject of discourse, or “had an

enormous currency,” among 18th-century thinkers, and the concept

played a crucial role in the rise of Romanticism in the arts, and has been an

important concept ever since. What I have found particularly interesting in my

research in the history of the sublime is the important role that the sublime

played in Romantic Poetry in particular. For example, the

Handbook of Romanticism Studies

states, “Scholars of the period consider the sublime to be a particularly

Romantic aesthetic or poetic commonplace, as so much poetry of the Romantic

period asks its readers to believe that poetry is at the same time immortal yet

insufficient to express the very things it means to say. This theme of

inexpressibility is also common in Romantic poetry, and is grounded in the

sublime” (56).

As I had anticipated, I found that the sublime is the most prominent in

Romantic Poetry. I also discovered that the most notable romantic poet working

with the sublime was William Wordsworth. Perhaps the relationship between poetry

and the sublime has intrigued me the way that it has because it further

establishes my belief in poetry as an effective translator of otherwise

inexpressible feelings. In other words, the sublime “transcends or overwhelms

human perception or expression” and is characterized by “incomprehensible

excesses of natural force,” but poetry somehow has the capacity to express and

make comprehensible feelings associated with the sublime by bringing out a

powerful mixture of pleasure and pain in its readers. I believe this holds true

not only with poetry, but also with other powerful forms of art that don’t

directly express the sublime, but indicate beauty and terror, or evoke pleasure

and pain.

The

Sublime in Contemporary Photography

After

taking note of the immense presence of imagery in poetry we’ve read throughout

the semester that depicts the sublime, and after viewing the Romantic paintings

of Caspar David Friedrich, J. M. W.

Turner, and Asher B. Durand that powerfully display the sublime, I became

interested in discovering to what extent the sublime persists in contemporary

visual arts. In my research, I can came across an incredibly useful website,

tate.org, that categorizes and exemplifies the sublime in different eras and in

different schools of art, as well as demonstrates how the concept of the sublime

has changed over time. I discovered through this site that the embodiment of

beauty and terror, and the aura of pleasure and pain still exist widely in

contemporary visuals arts.

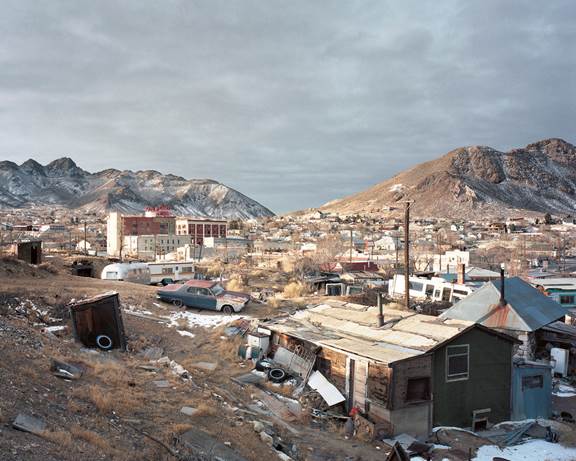

However, the images I chose to feature in this project to exemplify the sublime in contemporary photography are images from the series Grays the Mountain Sends by the internationally renowned, award-winning photographer Bryan Schutmaat, a.k.a. my big brother. Schutmaat states:

Grays the Mountain Sends combines portraits, landscapes, and still lifes in a series of photos that explores the lives of working people residing in small mountain towns and mining communities in the American West. Equipped with a large format view camera, and inspired by the poetry of Richard Hugo, I’ve aimed to hint at narratives and relay the experiences of strangers met in settings that spur my own emotions. Ultimately, this body of work is a meditation on small town life, the landscape, and more importantly, the inner landscapes of common men.

While Schutmaat’s objective wasn’t to capture the sublime, his poetic images

certainly, and uniquely, combine beauty with terror on an elevated scale, and

the experience of viewing his photographs brings on a powerful mixture of both

pleasure and pain.

Similar to the paintings of the Romantic Era that are both haunting and

beautiful, many of Schutmaat’s photographs, like the following, display the

overwhelming beauty of American landscapes, while simultaneously inducing

feelings of anxiety and dread.

In the following photograph, Schutmaat captures the notion of the

incomprehensible, awe-inspiring excesses of natural force that is often

associated with the sublime.

In many other photographs, like the following, tragedy stands at the forefront

of the image, inducing trepidation. Reminiscent of Sylvia Plath’s poetry, in

many of Schutmaat’s photographs, catastrophe, heartbreak, or pain takes lead.

However, they also evoke something overwhelmingly beautiful. Whether we find

this beauty in our tenderness toward the inhabitants of the land Schutmaat

photographs, or through the presence of the calm, natural landscape juxtaposed

with catastrophe, his images embody both an overpowering sadness and a profound

beauty, and consequently exemplify the sublime.

One of the most captivating and unique features of Schutmaat’s work, which sets

him apart from other contemporary photographers of the sublime, is his ability

to capture the sublime in portraits. While most contemporary photographers of

the sublime rely exclusively on landscape to convey the sublime, Schutmaat also

depicts the sublime by situating his subjects within natural, sublime settings.

In the following image, Schutmaat evokes both beauty and sadness, and pleasure

and pain, not only through the natural setting, but also through the body

language and expression of his subject.

In my

exploration of the sublime, I discovered the origins of the sublime and its

importance to Romantic Poetry, and how the sublime has persisted after the

Romantic Era and in other forms of art. However, another question I hoped to

answer, as I continually asked myself throughout my research, was whether or not

the sublime was exclusively a natural phenomenon or was something that could be

staged, or artificially created. When reflecting on moments of my own life in

which I experienced the sublime, such as the moment I stood on a mountaintop on

La Costa Brava of Spain or on the day my son was born, I thought of the sublime

as something that happened naturally and unexpectedly, and was a phenomenon

outside our control.

However, I learned in my research that the sublime is more accessible than I had

initially believed. Often times romantic writers, painters, or contemporary

romantic photographers, go in pursuit of the sublime by seeking isolation in the

natural world. That isn’t to say that moments of the sublime can be controlled,

or staged or artificially created, or are even easily attainable, but it is

certainly possible to seek, discover, and experience moments of the sublime. In

short, through my research and hours of contemplation, I’ve come to the

conclusion that we cannot create the sublime, but we can pursue, attain, and

capture and convey the sublime in art.

Works

Cited

Faflak, Joel, and Wright, Julia M., eds. Critical Theory Handbooks : Handbook of

Romanticism Studies. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. ProQuest ebrary.

Web. 13 May 2015.

Pillow, Kirk E. "Sublime, The." Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. Donald M.

Borchert. 2nd ed. Vol. 9. Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006. 293-294.

Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 13 May 2015.

Schutmaat, Bryan. Grays the Mountain

Sends. New York: Silas Finch, 2013.

"Sublime, The." Bloomsbury Guide to Human Thought. N.p.: Bloomsbury, 1993. Credo Reference. 1 Jan. 2002. Web. 13 May 2015.

|

|

|

|